Nathaniel Mayer Part 1 (Excerpt)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clyde Mcphatter 1987.Pdf

Clyde McPhatter was among thefirst | singers to rhapsodize about romance in gospel’s emotionally charged style. It wasn’t an easy stepfor McP hatter to make; after all, he was only eighteen, a 2m inister’s son born in North Carolina and raised in New Jersey, when vocal arranger and talent manager Billy | Ward decided in 1950 that I McPhatter would be the perfect choice to front his latest concept, a vocal quartet called the Dominoes. At the time, quartets (which, despite the name, often contained more than four members) were popular on the gospel circuit. They also dominated the R&B field, the most popular being decorous ensembles like the Ink Spots and the Orioles. Ward wanted to combine the vocal flamboyance of gospel with the pop orientation o f the R&B quartets. The result was rhythm and gospel, a sound that never really made it across the R &B chart to the mainstream audience o f the time but reached everybody’s ears years later in the form of Sixties soul. As Charlie Gillett wrote in The Sound of the City, the Dominoes began working instinctively - and timidly. McPhatter said, ' ‘We were very frightened in the studio when we were recording. Billy Ward was teaching us the song, and he’d say, ‘Sing it up,’ and I said, 'Well, I don’t feel it that way, ’ and he said, ‘Try it your way. ’ I felt more relaxed if I wasn’t confined to the melody. I would take liberties with it and he’d say, ‘That’s great. -

Big Al's R&B, 1956-1959

The R & B Book S7 The greatest single event affecting the integration of rhythm and blues music Alone)," the top single of 195S, with crossovers "(YouVe Got! The Magic Touch" with the pop field occurred on November 2, 1355. On that date. Billboard (No. 4), "The Great Pretender" and "My Prayer" (both No. It. and "You'll Never magazine expanded its pop singles chart from thirty to a hundred positions, Never Know" b/w "It Isn't Bight" (No. 14). Their first album "The Platters" naming it "The Top 100." In a business that operates on hype and jive, a chart reached No. 7 on Billboard's album chart. position is "proof of a record's strength. Consequently, a chart appearance, by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, another of the year's consistent crossover itself, can be a promotional tool With Billboard's expansion to an extra seventy artists, tasted success on their first record "Why Do Fools Fall In Love" (No. 71, positions, seventy extra records each week were documented as "bonifide" hits, then followed with "I Want You To Be My Girl" (No. 17). "I Promise To and 8 & B issues helped fill up a lot of those extra spaces. Remember" (No. 57), and "ABCs Of Love" (No. 77). (Joy & Cee-BMI) Time: 2:14 NOT FOR S»U 45—K8592 If Um.*III WIlhORtnln A» Unl» SIM meant tea M. bibUnfmcl him a> a ronng Bnc«rtal««r to ant alonic la *n«l«y •t*r p«rjform«r. HI* » T«»r. Utcfo WIIII* Araraa ()•• 2m«B alnft-ng Th« WorM** S* AtUX prafautonaiiQ/ for on manr bit p«» throoghoQC ih« ib« SaiMt fonr Tun Faaturing coont^T and he •llhan«h 6. -

Road Notez AJ Swearingen & J Beedle ($22.50) Jan

--------------- Calendar • On The Road --------------- Hatebreed have announced the first leg of Aaron Lewis Dec. 7 Egyptian Room Indianapolis their tour to support their new album, The Afghan Whigs Dec. 31 Bogart’s Cincinnati Divinity of Purpose, due out sometime early Road Notez AJ Swearingen & J Beedle ($22.50) Jan. 19 The Ark Ann Arbor next year. The tour starts in the legendary Alabama Shakes Dec. 1 Riviera Theatre Chicago Machine Shop in Flint, Michigan on Janu- CHRIS HUPE All That Remains w/Nonpoint ($9.89 adv., $13 d.o.s.) Dec. 13 Piere’s Fort Wayne ary 26. Though no other regional dates have All Time Low w/Yellowcard Jan. 18 Orbit Room Detroit been announced, they tour will likely pass through here in March or April. Shadows Fall, Andre Williams ($25) Jan. 5 Magic Bag Ferndale, MI Andrew Bird Dec. 19-20 Forth Presbyterian Church Chicago Dying Fetus and The Contortionist open the Flint show. Avett Brothers Feb. 12 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor There were rumors a few weeks ago that Coal Chamber were reforming and going on tour Bela Fleck w/The Cleveland Orchestra Dec. 6-8 Severance Hall Cleveland with Sevendust. While the Coal Chamber reformation still looks like it’s going to happen Bergamot w/Five Minute Fan Club and Kevin Daniels & Friends ($8) Dec. 15 Martyrs’ Chicago Betty ($19) Dec. 17 The Ark Ann Arbor in 2013, it appears the tour with Sevendust isn’t happening, at least not yet. Sevendust, Big Gigantic Dec. 31 Aragon Ballroom Chicago who have appeared in The Fort many, many times, announced they will be co-headlining Big Gigantic Feb. -

ANDRE WILLIAMS' 60Th Birthday Party

ANDRE WILLIAMS' 60th Birthday Party Nov. 8. 1996 Some people fall through the cracks. But Chicago soul singer Andre Williams broke off and blew away, like the last leaf of autumn in a bitter wind. A jive-talking songwriter-producer during the Chicago soul music renaissance of the mid-1960s, Williams had his own dance hits like "Jail Bait" and "Bacon Fat." He also discovered Alvin Cash, who in 1963 had a national hit with "Twine Time." In the fall of 1994, I tried to help songwriter-producer Ben Vaughn find Williams , a.k.a. "Mr. Rhythm." Vaughn wanted to include Williams in the critically acclaimed Elektra/Nonesuch American Explorer Series. The records championed overlooked taproot artists like Jimmie Dale Gilmore and zydeco star Boozoo Chavis. In 1993 Vaughn lovingly produced the late soul singer Arthur Alexander's "Lonely Just Like Me" for the series, and he wanted to produce Williams . The trail dried up with Cash, who said Williams was "in a hospital somewhere." On a recent Sunday, Williams sat alone at Beat Kitchen on the north side of Chicago, where he will front a five-piece band to celebrate his 60th birthday. Opening acts include Chicago doo-wop group legends the El Dorados and former Chess Records vocalist Jo Ann Garrett. Current El Dorados include lead vocalist Pirkle Lee Moses Jr., who founded the group in 1952, and second tenor Larry Johnson of the Moroccos. "I knew you were looking for me," Williams said as a sly smile crept out from under his tan wide-brim hat. "I was in drug rehabilitation and a super depression. -

An Examination of Essential Popular Music Compact Disc Holdings at the Cleveland Public Library

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 435 403 IR 057 553 AUTHOR Halliday, Blane TITLE An Examination of Essential Popular Music Compact Disc Holdings at the Cleveland Public Library. PUB DATE 1999-05-00 NOTE 94p.; Master's Research Paper, Kent State University. Information Science. Appendices may not reproduce adequately. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audiodisks; Discographies; *Library Collection Development; *Library Collections; *Optical Disks; *Popular Music; *Public Libraries; Research Libraries; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Cleveland Public Library OH ABSTRACT In the 1970s and early 1980s, a few library researchers and scholars made a case for the importance of public libraries' acquisition of popular music, particularly rock music sound recordings. Their arguments were based on the anticipated historical and cultural importance of obtaining and maintaining a collection of these materials. Little new research in this direction has been performed since then. The question arose as to what, if anything, has changed since this time. This question was answered by examining the compact disc holdings of the Cleveland Public Library, a major research-oriented facility. This examination was accomplished using three discographies of essential rock music titles, as well as recent "Billboard" Top 200 Album charts. The results indicated a strong orientation toward the acquisition of recent releases, with the "Billboard" charts showing the largest percentages of holdings for the system. Meanwhile, the holdings vis-a-vis the essential discographies ran directly opposite the "Billboard" holdings. This implies a program of short-term patron satisfaction by providing current "hits," while disregarding the long-term benefits of a collection based on demonstrated artistic relevance. -

THE VOLEBEATS the Volebeats Rainbow Quartz/Sonic

THE VOLEBEATS the Volebeats Rainbow Quartz/Sonic BIOGRAPHY The Volebeats' new album is an epic double-LP affair, recorded in the heart of Detroit, Michigan. Throughout these 19 new songs, the group that Ryan Adams once called "the best American band" are in top form, proving themselves to be more prolific than ever. The Volebeats is a definitive work from a favorite band of many musicians and critics, and it's their first new album since 2005's Like Her LP. The Volebeats began developing their particular brand of country-influenced rock n' roll, with Motown hooks and British Invasion harmonies, in Detroit in the late 1980's. Over two decades, they've released a string of critically-acclaimed albums. They've toured in the USA, Canada, England, and Spain. During a tour with Whiskeytown in the 90's, Ryan Adams actually joined the Volebeats for a week, playing onstage with them and co-writing the song "Everytime" with the group's main songwriters Jeff Oakes and Matthew Smith. The Volebeats appeared onscreen in the movie Shopgirl, playing "Somewhere in my Heart". Also, the Volebeats' "Two Seconds" was covered by country-rock chanteuse Laura Cantrell on her debut LP. This new self-titled LP is the product of a new phase of intense songwriting and recording activity for the band. Singer Jeff Oakes and guitarist Matthew Smith wrote most of the songs. Jeff appeared at Matt's doorstep with notebooks filled with lyric ideas. Very quickly, these scribbled notes were transformed into full-blown songs with hooks, melodies, riffs, and harmonies. -

Paquete De Patrocinio

NOTA DE PRENSA: 2011 5º Festival Internacional “BLUES AT MOONLIGHT” 5º Festival Internacional “BLUES AT MOONLIGHT” 25-26-27 Noviembre 2011 Hotel Sunset Beach Club – Benalmádena www.bluesatmoonlight.com Del 25 al 27 de Noviembre tendrá lugar en Benalmádena Costa la 5ª edición del Festival “Blues At Moonlight” de Benalmádena organizado por Active Sound Productions y la inestimable colaboración del Hotel Sunset Beach Club. El Festival crece cada año y para el 2011 contará con un programa de 15 actuaciones de máximo nivel: 7 grupos son de fuera de España (3 son de Estados Unidos –Andre Williams de Detroit, The Goldstars de Chicago y Little Victor de Memphis, dos de Holanda – Miss Mary Ann y The Ragtime Wranglers, una de Inglaterra – Knocksville, y un0 de Francia – Crown Electric Combo) y 3 de la península (Blas Picon & The Junk Express de Barcelona, Help Me Devil de Madrid y Mississippi Martínez y Los Bastardos de Granada). Además el festival cuenta también con la actuación de cinco de los mejores disc jockeys de la escena “vintage” (DJ The Mojo Man de Estados Unidos, DJ Crackzorla Barcelona, DJ Paula Punkita de Cádiz, DJ Hamlet Bop de Málaga y DJ Tall Mike de Marbella). Cada artista nos obsequiará con su interpretación de los diferentes estilos del Blues, Rhythm & Blues, Rock and Roll, Rock-a-billy, Punk Blues, Soul, Garage Rock, Surf y Hot Swing más auténtico y genuino. 1 5º Festival Internacional “BLUES AT MOONLIGHT” 25-26-27 Noviembre 2011 Hotel Sunset Beach Club – Benalmádena www.bluesatmoonlight.com NOTA DE PRENSA: 2011 5º Festival Internacional “BLUES AT MOONLIGHT” Destacar en especial, por primera vez en Andalucía, la presencia de Andre Williams, toda una una leyenda en activo del género y su banda al completo que estará presentando su nuevo disco en directo para todos los asistentes al festival. -

African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Jennifer, "The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago" (2012). Dissertations. 688. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/688 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Searcy LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE VOICE OF THE NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO, WVON, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY/PUBLIC HISTORY BY JENNIFER SEARCY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jennifer Searcy, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their feedback throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. As the chair, Dr. Christopher Manning provided critical insights and commentary which I hope has not only made me a better historian, but a better writer as well. As readers, Dr. Lewis Erenberg and Dr. -

Ing the I Needs of the Music & Record 1111 Ilindustry

record Dedicated To Serving The I Needs Of The Music & Record 1111 IlIndustry Vol. 21, No. 1017 December 3, 1966 in the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK WHO TELL IT TO THE RAIN IN THE ,THE 4 SEASONS The sensational 'Last Train to Always hardy perennials, the 4 Here's a pretty song Herman Clarksville" is followed by what Seasons have a new song, "Tell and the Hermits sing with a sounds like an even more sen- It to the Rain," that sounds strong tinge of melodic feeling. sational one-"I'm a Believer" very contemporary, very Bob "East West" should be a power- WORLD -penned by Neil Diamond (Col - Crewe. Never rains but it pours ful contender east to west gems 1002). (Philips 40412). (MGM 13639). SLEEPERS OF THE WEEK % LUCKY L1Nor WHAT IS SOUL? BEN E. KING ,4,44444......44444444444, One of the soul kings, Ben E. Keith Relf of the Yardbirds How '20s can you get? Here's a King, sets out to define an steps into the solo spotlight guy dubbed Stutz Bearcat (Mur- elusive term on "What is Soul." with this wildly -arranged side ray Roman) singing the Charles Will spur many a soul sell at- that has to be heard to be Lindbergh song, "Lucky Lindy." tack (Atco 6454). believed (Epic 5-10110). Should skidoo up the charts (Warner Bros. 5817). 1 LBI ".JIS OF THE WEEK Epic's Dave Clark 5 1AytAmcIRiCAfvs GREA-rIS1 Vl)i.klME 2 GcyiNç MaRia Slop The Clock & Their 14 Gold Disks MavdayMlondAy SundayAwl ME f.iviaí At>ovclfou* HeAd - Dave's Extraordinary TwEKry Fou« Hou«s F«oaºTidsa CRawada 'lit NArect Asour4d Silly Boy, Gist Business Achievements Why CANY'You &dog Me Home are "Crying," Discussed This Issue. -

PPCA Licensors Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights

PPCA Licensors Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights 88dB Bowles Production *ABC Music Brian Lord Entertainment ACMEC Bridge, Billy Adams, Clelia Broad Music AGR Television Records Buckley, Russell Aitken, Gregory A. Budimir, Mary Michelle AITP Records Bullbar P/L aJaymusic Bulletproof Records t/a Fighterpilot AJO Services Bulmer, Grant Matthew Allan, Jane Bunza Entertainment International Pty Ltd Aloha Management Pty Ltd Butler Brown P/L t/a The John Butler Trio Alter Ego Promotions Byrne, Craig Alston, Chris Byrne, Janine Alston, Mark *CAAMA Music Amber Records Aust. Pty Ltd. Cameron Bracken Concepts Amphibian *Care Factor Zero Recordz Anamoe Productions Celtic Records Anderson, James Gordon SA 5006 Angelik Central Station Pty Ltd Angell, Matt Charlie Chan Music Pty Ltd Anthem Pty Ltd Chart Records and Publishing Anvil Records Chase Corporation P/L Anvil Lane Records Chatterbox Records P/L Appleseed Cheshire, Kim Armchair Circus Music Chester, John Armchair Productions t/a Artworks Recorded Circle Records Music CJJM Australian Music Promotions Artistocrat P/L Clarke, Denise Pamela Arvidson, Daniel Clifton, Jane Ascension World Music Productions House Coggan, Darren Attar, Lior Col Millington Prodcutions *Australian Music Centre Collins, Andrew James B.E. Cooper Pty Ltd *Colossal Records of Australia Pty Ltd B(if)tek Conlaw (No. 16) Pty Ltd t/a Sundown Records Backtrack Music Coo-ee Music Band Camp Cooper, Jacki Bellbird Music Pty Ltd Coulson, Greg Below Par Records -

Rick Richards' Fortune Records – Page 1

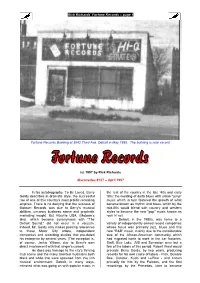

Rick Richards’ Fortune Records – page 1 Fortune Records Building at 3942 Third Ave. Detroit in May 1995. The building is now vacant. (c) 1997 by Rick Richards discoveries #107 – April 1997 In his autobiography, To Be Loved, Berry the rest of the country in the late '40s and early Gordy describes in dramatic style, the successful '50s: the melding of delta blues with urban "jump" rise of one of this country's most prolific recording music which in turn fostered the growth of what empires. There is no denying that the success of became known as rhythm and blues, which by the Motown Records was due to Berry's musical mid-50s would blend with country and western abilities, uncanny business sense and prophetic styles to become the new "pop" music known as marketing insight. But Hitsville USA, (Motown's rock 'n' roll. aka), which became synonymous with "The Detroit, in the 1950s, was home to a Detroit Sound," did not occur in a vacuum. variety of independently owned record companies Indeed, Mr. Gordy only makes passing references whose focus was primarily jazz, blues and this to those Motor City artists, independent new "R&B" music, mainly due to the considerable companies and recording studios that pre-dated size of the African-American community which his enterprise by several years. (The exception is, had migrated north to work in the car factories. of course, Jackie Wilson, due to Berry's own Staff, Blue Lake, JVB and Sensation were but a direct involvement with that singer's career). few of the labels of this period. -

Detroit Blues Women Michael Duggan Murphy Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2011 Detroit blues women Michael Duggan Murphy Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Michael Duggan, "Detroit blues women" (2011). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 286. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. DETROIT BLUES WOMEN by MICHAEL DUGGAN MURPHY DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: HISTORY Approved by: ____________________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ DEDICATION “Detroit Blues Women” is dedicated to all the women in Detroit who have kept the blues alive, to the many friends, teachers and musicians who have inspired me throughout my life, and especially to the wonderful and amazing family that has kept me alive. Many thanks to Lee, Frank, Tom, Terry, Kim, Allison, Brendan, John, Dianne, Frankie, Tommy, Kathy, Joe, Molly, Tom, Ann, Michael, Dennis, Nancy, Mary, Gerry, Charles, Noranne, Eugene, Maegan, Rebecca, Tim, Debby, Michael Dermot and Angela. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and committee chair John J. Bukowczyk for his friendship, his editing skills, and his invaluable guidance through all stages of this dissertation. Throughout my graduate career, Dr. Bukowczyk has been generous mentor with a great deal of insight into the workings of the University and the world at large.