ANALYSIS “The Light of the World” (1933) Ernest Hemingway (1899

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

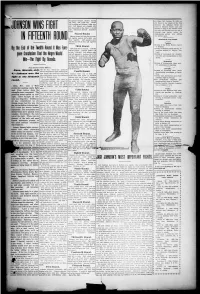

Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, a Public Reaction Study

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study Full Citation: Randy Roberts, “Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study,” Nebraska History 57 (1976): 226-241 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1976 Jack_Johnson.pdf Date: 11/17/2010 Article Summary: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, played an important role in 20th century America, both as a sports figure and as a pawn in race relations. This article seeks to “correct” his popular image by presenting Omaha’s public response to his public and private life as reflected in the press. Cataloging Information: Names: Eldridge Cleaver, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louise, Adolph Hitler, Franklin D Roosevelt, Budd Schulberg, Jack Johnson, Stanley Ketchel, George Little, James Jeffries, Tex Rickard, John Lardner, William -

Here Acts of Everyday Life Occur

Ann Hirsch Sculpture Studio Portfolio November 2017 2 Table of Contents Profile.......................................................................................................................5 Selected Projects....................................................................................................9 Curriculum Vitæ....................................................................................................45 Contact Information..............................................................................................50 First Image: Home, East Entryway to Patriot Plaza, Sarasota National Cemetery, Sarasota, FL, 2014 Commissioned by the Patterson Foundation Bronze, stainless steel and boralstone, 17’ x 6’ x 3’ Photo Credit: Sean Harris This page: Saint Walking, Bronze, life-size, Akron, OH 4 PROFILE Sculptor and public artist Ann Hirsch has worked throughout the U.S. on projects such as Home (2014), a transitional space into Patriot Plaza at Sarasota National Cemetery which was com- missioned by the Patterson Foundation and includes large for- mat bronze Bald Eagles’ nests; and the Bill Russell Legacy Proj- ect (2013-2015) which was commissioned by the Boston Celtics Shamrock and comprises three statues in bronze set within a field of granite and brick elements that is part sculpture and part inter- active playground. Other projects include several site-specific bronze figures that build upon and move beyond traditional statuary through stag- ing interactive encounters with the public, broadening the land- scape -

Fight in the Fifteenth

1 son appears stronger clinches forcing at Colma CaL October 16 1909 are Jeff back Jeff sends left Clinch still fresh in the minds of the ring 1 Jeff is smiling and Johnson looks wor- ¬ followers He defeated Burns on ried Jeff slipped into straight left points in fourteen rounds and put but was patted on the cheek a second Ketchel to selep in the twelfth round bell Anybodys later Clinchedat the His fight with Ketchelwas the last of- 1 round Johnsons ring battles before the Second Round championship contest with Jeffrie Johnson slings left into ribs another was agreed upon jab slightly marred Jeffs right eye They sparred Jeff assumes such SPORTS OF THE WEEK Johnson sent left to chin and uppercut with left Tuesday Opening of the Royal Henley regatta Third Round In England End of Twelfth Round It Was Fore- ¬ By the the Jeff sends left to stomach Clinches Opening of Brighton Beach Racing As- ¬ and they break Johnson dashes left sociation meeting at Empire City to nose Clinched Jack missed right track gone Conclusion That the Negro Would and left uppercuts Johnson tries with Opening of tournament for Connecti- ¬ a vicious right to head but Jim ducks cut state golf championship at New and clinches Jack is cautious in break- ¬ Haven WinThe Fight By Ronnds away Johnson sends two little rights to head Clinches Johnson tries with Wednesday an uppercut but Jim sent a light left Opening of international chess mast- ¬ to short ribs Just before the bell Jeff ers tournament at Hamburg light hand to head Even From Mondays Extra Edition sent left at end -

Phil's Hair Styling

June / July 2014, Polish American News - Page 5 Museum’s Historic Reflections Project Part 2 Yolanda Konopacka DeSipio of June 9, 1922 - Jozef Tykocinski - (Made sound Bennett, Bricklin & Saltzburg, LLP possible in motion pictures) Attorneys at Law • Call: (215) 423-4824 Jozef Tykocinski was a Polish engineer and inventor Available to assist clients throughout the from Wloclawek, Poland. In 1922, Tykocinski publicly Philadelphia area & New Jersey in both the demonstrated for the first time that sound was English and Polish Languages possible on film in motion pictures. He was awarded the patent in 1926. Immigration, Personal Injury, June 10, 1982 - Tara Lipinski (Born) Worker’s Compensation & Real Estate Tara Lipinski is a Polish American who at the age of 15 became the youngest winner of the Women’s Figure Skating Championship. She then proceeded to win a Subscribe to the Gold Medal at the 1998 Olympic Winter Games held in Nagano, Japan. Polish American Journal June 11, 1857 - Antoni Grabowski (Born) Published Since 1911 Antoni Grabowski was a Polish chemical engineer known News from Polish American Communities Across the United States for compiling the first chemistry dictionary in the Polish News - Sports - Religion - History - Recipes - Folklore - Polka - and More! language. He was also an activist of the early Esperanto movement, and his translations had an influential impact Published Monthly - Only $18.00 per year on the development of Esperanto into a language of Call (toll free) 1(800) 422-1275 or visit us on the web at: literature. www.PolAmJournal.com June 12, 1887 - Polish Falcons of America (Founded) e-mail: [email protected] The Polish Falcons of America is a fraternal insurance benefit society headquartered in Pittsburgh, PA. -

SPORTS and WARNER PATHE NEWSREELS

JOHN E. ALLEN, INC. JEA 1S12 - SPORTS and WARNER PATHE NEWSREELS <03/96> [u-bit #19200289] 2066-1-4 09:00:13 1) men playing cards outdoors, Mrs. Jeffries and women sitting (S) Sports: Boxing on bench behind them watching and talking (1910) Johnson/Jeffries 09:00:55 PAN across empty arena with workers finishing construction, [also on 1X48 men standing around including man with camera 01:51:58-01:55:23] 09:02:06 crowd in stadium [also see 1S06 09:02:18 Jack Johnson and men in business suits running on dirt road 02:35:41-02:57:40] 09:02:29 corner men waving towels at boxers to cool them off after round five [also partially 09:02:56 TRUCKING shot of crowd in street, people looking and some waving on 1B08 to camera, storefronts, sign on building: “Official Headquarters 08:57:01-08:59:43] - Jeffries Johnson Fight”, tavern 09:04:29 Jack Johnson and men running on dirt road while men in car and dog -09:04:46 following during training 09:04:49 2) Walter Dukes profile - sign: “Seton Hall University” in South (N) Sports: -09:09:36 Orange, N. J., African-American basketball player studying Basketball - College - in his room, in library, practicing radio announcing, walking Seton Hall down steps of building, practicing basketball, Duke being [sound] interviewed by reporter, another player Richard Reagan being interviewed, game action of Seton Hall beating Fordham 09:09:38 3) “Michigan Outlasts Pitt” - game action (85-78), one (N) Sports: -09:11:09 African-American player for Michigan, cheerleaders Basketball - Telenews -3- [sound] 09:11:12 4) golf club of African-American women playing in tournament in (N) Blacks: Sports -09:12:14 Washington, D.C. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

(Perth Amboy, NJ). 1915-12-23

Y. M. C. BOYS IN ANOTHER COURT VICTORY-ROOSEVELT AND METUCHtN BOWLERS WIN 1 SCOOP REPORTER Only Two More Days Till Christmas By HOP" - 1 5tCûND 5 THIR.D CHANG€- ; CHANGÉ. I CHANGE, j .OF MIND OF MIND/ ? OFMlND^i - VERN1 LATEST , RtC&_ / 5TITCH B12NUSS0F sTmv(H(r u <J CHANGE. TO CROCHET^—^ AN XMA5 PRESENT OFMtHT) FOR W\F "(SPORT 5CARF-CAP> AND SWEATtR- , Western Miner After Middleweight Crown IN ROUGH GAME, ST. PETERS Described As Second Stanley Ketchel ROOSEVELT BOWLERS Ï. IH. G. DEFEATS AMBOY 5; JUREE STRAIGHT FROM THE - HORNSBY GETS 14 FOULS LEADERS, METUCHEN WINS match t On the parish house court las* out of five chances in the second . W. L. Per. In the respective game». In this arid night Ray Weldon's blue-garbed toss- period he accepted four. Ma>ir,u.e 45 28 17 .644 "Cobb" Clarkson rolled 220 205; .... rolled 208 ers downed the Amboy Five, a team Allen and Grace ably looked after Perth Amboy 4B 27 18 .600 JohiiHon made 210; Kreps composed of well known Middlesex Thomas and Regan, while Cantlon, Roosevelt .. 45 24 21 .53» und Γ 205. 21 are scores of the two county tossers. The score, 26 to !>, who was the name game little tossor Metuclien 42 21 .600 These the South 45 18 27 .400 matches rolled last night: does not do justice to the game, which as of the good old Riverside days, Amboy postponed * 42 14 28 .333 Hoosevelt. was a hard fought battle from the gave flashes of good floor work. -

Name: Stanley Ketchel Career Record: Click Alias: the Michigan Assassin

Name: Stanley Ketchel Career Record: click Alias: The Michigan Assassin Birth Name: Stanislaus Kiecal Nationality: US American Birthplace: Grand Rapids, MI Born: 1886-09-14 Died: 1910-10-15 Age at Death: 24 Height: 5' 9 Managers: Joe O'Conner, Willus Britt Career Overview One of the real “characters” of boxing, Ketchel was a fearless man whose personality was perfectly reflected by his in-the-ring savagery and dramatic life. The first two-time middleweight champ of the gloved era, he is also considered to be possibly the hardest hitting of all middleweight champions. An unpolished brawler who loved to test an opponent’s will to fight, the “Michigan Assassin” faced four hall of famers during his career, some of history’s best middleweights, light heavyweights, and heavyweights included among them. Nat Fleischer, the late ring historian and founding editor of The Ring magazine, considered Stanley to be the greatest middleweight in history. Early Years Born Stanislaus Kiecal to Polish immigrants in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Ketchel was a rough, tough brawler even as a youth. He avoided school, instead falling in with a gang of street kids and often getting into fist fights. At twelve years old, he ran away from home, becoming a child hobo. As a teenager he lived in Butte, Montana, where he found employment first as a hotel bellhop and then as a bouncer. This profession obviously led to many scraps that established his reputation as the best fist fighter in town. Soon enough sixteen-year-old Stanley was performing in backroom boxing matches with older locals for twenty dollars a week. -

Fairview AMERICA.! ASSOOIXATIOX for the Best of Meats

SPORTS MOyiES COUNTY CORRESPONDENCE CLASSIFIED MARKETS COMICS TEN PAGES SECTION TWO PAGES 7 TO-1-0 u --a r 881 . 2 S&BrK DAILY EAST OREGONIAN, PENDLETON, OREGON; FRIDAY EVENING, MAY 21, 1920 MIDDLEWEIGHT CHAMPION WHOSE DEFEAT OF CUP DEFENDER WILL PORTLAND TOOK GAME MIKE O'DOWD SURPRISED THE BOXING FANS HAVE TERRIFIC BOUT! PACE TRYOUT TESTS! FROM SAN FRANCISCO! OAKLAND, May 21. Portland won ronTLAJTD, Or., May 21. In one CITY ISLAND, X. T-- . May 21. a slugfest from San Francisco, 10 to X. of the moot terrific firing ever een In America's eup candidate Vanitle left Couch was replaced by McQuMile In Portland, young ltrown and Joe Oor hero at noon todny for Morris Cove, the sixth after allowing nine hits and uuui xlwcffed and slashed thflr way seven runs. Kamm was chased by through ten round here lost night to New Haven, where tomorrow she will Umpire Byron In the ninth for disput- a draw. Peter Mitchle received a meet the flag officers' yacht Jlesolute ing a decision and In the same inning hard luoln at the hand of Puggy In the first of the long series of races Cutcher Baker retired with an Injured Morton, who eaelly won the dccMon to pick the craft that Is to meet Mr hand by off caused a foul tip. after elrht rounds. Frankle Monroe Thomas Upton's Shamrock IV Portland, 10 IS I San JYanclsco and Wing an eight Sandy Hook In July. 13 2. Weldon ataced way round draw, Hoke knocked out Zim- The yacht has been on the at Schrocdcr, Southerland and Baker, merman in the third round. -

Exceptional July SPECIALS

14 THE FORT WAYNE NEWS AND SENTINEL Friday, July 12. P1TTSBURG RUNNER RACE FOR OWN MONEY STARS IN QUARTER l> Circulation JBternational Sweepstakes to for June Run Sunday, July 28. Exceptional July SPECIALS 'For the first tlm« in the history of automobile racing the fastest drivers m That cannot fail to attract the attention of every intelligent and economical buyer of men's and boys' wear 33,790 world are going to race for their money. This is th« announcement within reach of Fort Wayne. * today by Manager Charles H For- 1.... 34,371 Sun. of the Chicago speedway. The race 2.... Sun. 33,650 twin be held there on Sundav Jul\ 28 Watch Our Windows 3..., 34,264 .33,420 •Ml »ll be known as the international 4.... 33,298 sweepstakes. It will have a value of S. .. 33.278 That are Making This "Fort Wayne's Best Clothing Store" 6 . 33388 T7nd*r the conditions of the race the 7 . 33,498 fletut drivers will be invited to Con The Busiest Place in Town 8 34,712 pile, only those known to have «*rs ca- 9 Sun. piWe of making more than 105 mles per 10.... 33,579 Iwor being invited Each drher will 11 33,638 bftre to put up 12,000 and the speedwm Men's $1.50 Fancy Madras 25c Wash Men's $2.00 Summer Shirts 12.... 33.632 wttl add enough to bring the total to 13 ....33,622 W.OOO. SHIRTS TIES All sizes—all patterns 14 ....33,642 "Heretofore the riders have alwa>s 15. -

"Montana's Centennial: Our Cultural Legacy" Max S

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Max S. Baucus Speeches Archives and Special Collections 1-1-1990 "Montana's Centennial: Our Cultural Legacy" Max S. Baucus Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/baucus_speeches Recommended Citation Baucus, Max S., ""Montana's Centennial: Our Cultural Legacy"" (January 1, 1990). Max S. Baucus Speeches. 448. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/baucus_speeches/448 This Speech is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Max S. Baucus Speeches by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Printing, Graphics & Direct Mail ONBASE SYSTEM Indexing Form Senator * or Department*: BAUCUS Instructions: Prepare one form for insertion at the beginning of each record series. Prepare and insert additional forms at points that you want to index. For example: at the beginning of a new folder, briefing book, topic, project, or date sequence. Record Type*: Speeches & Remarks MONTH/YEAR of Records*: January-1990 (Example: JANUARY-2003) (1) Subject*: None (select subject from controlled vocabulary, if your office has one) (2) Subject* Montana Centennial: Our Cultural Legacy DOCUMENT DATE*: 01/01/1990 (Example: 01/12/1966) * "required information" 1111 BAUCU ,TlAA/ A*Rk- 4 !R! UNIT P; GENF 201, 'DYNAMIC1', 12, 32, 126, 32, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0; FONT 201; SFA 7, 18, P; EXIT; SPEECH BY SENATOR MAX BAUCUS MONTANA'S CENTENNIAL: OUR CULTURAL LEGACY Former Ambassador and Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield once said that "to me Montana is a symphony.. -

Polish American Cultural Center Museum in Philadelphia, PA

June / July, 2009, Polish American News - Page 10 Polish American Cultural Center Museum in Philadelphia, PA June 9, 1922 - Jozef Tykocinski - (Made sound Museum’s Historic Reflections Project possible in motion pictures) June / July Jozef Tykocinski was a Polish engineer and inventor from Wloclawek, Poland. In 1922, Tykocinski publicly The Polish American Cultural Center Museum in Historic demonstrated for the first time that sound was Philadelphia presents Historic Reflections from Polish and Polish possible on film in motion pictures. He was awarded American history on the Polish American Radio Program. The the patent in 1926. reflections are organized in a daily format. Some of the dates may be the birthday or death date of a prominent person. Other dates may June 10, 1982 - Tara Lipinski (Born) celebrate a milestone in a prominent person’s life such as a career Tara Lipinski is a Polish American who at the age of promotion, invention date, or some accomplishment that contributed 15 became the youngest winner of the Women’s Figure to science, medicine, sports, or entertainment history. Other dates Skating Championship when she won a Gold Medal at may be an anniversary of a historical event in Polonia or Poland’s the Olympics held in Nagano, Japan in 1998. history. You can hear weekly historic reflections on the Saturday edition June 11, 1857 - Antoni Grabowski (Born) of the Polish American Radio Program at 11 A.M. on 1540 AM Antoni Grabowski was a Polish chemical engineer known Radio from Philadelphia. Listen to rebroadcasts 24 hours a day at for compiling the first chemistry dictionary in the Polish PolishAmericanRadioProgram.com.