An Abstract of the Thesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012-2014 LA84 Foundation Biennial Report

2012-2014 BIENNIAL REPORT Board of Directors President Published biennially by the Frank M. Sanchez, Chair Anita L. DeFrantz LA84 Foundation Yvonne B. Burke Jae Min Chang Treasurer For additional information, John F. Chavez Marcia H. Suzuki please write or call: Anita L. DeFrantz Debra Kay Duncan Vice Presidents LA84 Foundation James L. Easton Patrick Escobar 2141 West Adams Boulevard Priscilla Florence Grants & Programs Los Angeles, California 90018 Jonathan Glaser Robert V. Graziano Wayne Wilson Telephone: 323-730-4600 Mariann Harris Communications & Education E-mail: [email protected] Rafer Johnson Home Page: www.LA84.org Stan Kasten Robert W. Wagner Maureen Kindel Partnerships Patrick McClenahan Like us on Facebook Peter V. Ueberroth Walter F. Ulloa Gilbert R. Vazquez Follow us on Twitter John Ziffren Thomas E. Larkin, Jr., Board Member Emeritus Peter O’Malley, Board Member Emeritus Published July 2014 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR: On June 18, 2014, I had the honor of being elected Chair of the LA84 Foundation by my colleagues on the board. The timing of my election is particularly significant to me as we are celebrating the 30th Anniversary of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. The LA84 Foundation is the legacy of those Games. As I reflect back to the 1984 Olympic Games, one word comes to mind: excellence. There is no better word to describe the manner in which the Games were organized and delivered by my board colleague, Peter V. Ueberroth, his management team, staff and thousands of volunteers. I recall the excellence displayed by the best athletes from around the world as they competed to earn Olympic medals. -

Chargers Agree to Terms with Tyrod Taylor

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, March 13, 2019 Chargers Agree to Terms with Tyrod Taylor The Los Angeles Chargers agreed to terms on a two-year contract with QB Tyrod Taylor, the organization announced on Wednesday. Taylor has appeared in 62 games with 46 starts. The 2011 sixth-round selection by the Baltimore Ravens has passed for 9,529 yards with 53 touchdowns to 20 interceptions while completing 61.6 percent of his passes. On top of his passing, Taylor has rushed for 1,836 yards for 16 touchdowns while sporting a 5.6 yards-per-carry average. The Virginia native earned his first Pro Bowl nod for his play during the 2015 season with the Buffalo Bills. Taylor threw for 20 touchdowns to only six interceptions while passing for 3,035 yards and sporting a career-best 99.4 passer rating. Taylor also added 568 yards on the ground and four rushing touchdowns. Taylor made his first starts in 2015 with Buffalo while Chargers Head Coach Anthony Lynn was the Running Backs/Assistant Head Coach for the Bills. Lynn took over as the offensive coordinator for the final 14 games of 2016 (including as the interim head coach for the season finale). With Lynn running the offense, Taylor threw for 2,615 yards and 14 touchdowns with five interceptions while also posting five games with a passer rating of a 100 or greater. He added six rushing touchdowns and 544 yards on 88 attempts (6.2 avg.). Taylor’s 20 combined touchdowns over that stretch tied for an NFL high in 2016 among quarterbacks. -

New York Giants 2012 Season Recap 2012 New York Giants

NEW YORK GIANTS 2012 SEASON RECAP The 2012 Giants finished 9-7 and in second place in the NFC East. It was the eighth consecutive season in which the Giants finished .500 or better, their longest such streak since they played 10 seasons in a row without a losing record from 1954-63. The Giants finished with a winning record for the third consecutive season, the first time they had done that since 1988-90 (when they were 10-6, 12-4, 13-3). Despite extending those streaks, they did not earn a postseason berth. The Giants lost control of their playoff destiny with back-to-back late-season defeats in Atlanta and Baltimore. They routed Philadelphia in their finale, but soon learned they were eliminated when Chicago beat Detroit. The Giants compiled numerous impressive statistics in 2012. They scored 429 points, the second-highest total in franchise history; the 1963 Giants scored 448. The 2012 season was the fifth in the 88-year history of the franchise in which the Giants scored more than 400 points. The Giants scored a franchise- record 278 points at home, shattering the old mark of 248, set in 2007. In their last three home games – victories over Green Bay, New Orleans and Philadelphia – the Giants scored 38, 52 and 42 points. The 2012 team allowed an NFL-low 20 sacks. The Giants were fourth in the NFL in both takeaways (35, four more than they had in 2011) and turnover differential (plus-14, a significant improvement over 2011’s plus-7). The plus-14 was the Giants’ best turnover differential since they were plus-25 in 1997. -

Download History of Diversity At

Diversity at the University of San Francisco: Select Historical Points Alan Ziajka, Ph.D. Associate Vice Provost for Academic Affairs and University Historian March 27, 2017 The University of San Francisco’s Vision, Mission, and Values Statement of September 11, 2001, declares that “as a premier Jesuit Catholic urban university”, the institution will: “Recruit and retain a diverse faculty of outstanding teachers and scholars and a diverse, highly qualified, service-oriented staff committed to advancing the University’s mission and its core values.” “Enroll, support and graduate a diverse student body, which demonstrates high academic achievement, strong leadership capability, concern for others and a sense of responsibility for the weak and the vulnerable.” Since 1855, USF has increasingly reflected the ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic diversity of the city and the nation, and by the late 1920s, women became important to that diversity as well. More recently, recognition and respect for the LGBTQ community has become part of USF’s commitment to diversity. Below are some select historical points that underscore the institution’s long-term commitment to diversity in all of its forms. Many American institutions of higher education partially reflect the nation’s immigration experience. During the nineteenth century, however, St Ignatius College was the immigration experience. The school was founded by Italian Jesuit immigrants, the first seven presidents of the college were all Jesuit immigrants, most of the faculty members were either Italian Jesuits or lay faculty from Ireland, and virtually all of the students during the school’s first five decades were first- or second-generation Irish or Italian Catholics, to be joined by the end of the 19th century by students of German, French, and Mexican ancestry. -

Colin Kaepernick's Collusion Suit Against the NFL

Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 4 3-1-2019 The Eyes of the World Are Watching You Now: Colin Kaepernick's Collusion Suit Against the NFL Matthew McElvenny Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew McElvenny, The Eyes of the World Are Watching You Now: Colin Kaepernick's Collusion Suit Against the NFL, 26 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 115 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol26/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\26-1\VLS104.txt unknown Seq: 1 21-FEB-19 11:37 McElvenny: The Eyes of the World Are Watching You Now: Colin Kaepernick's Co THE EYES OF THE WORLD ARE WATCHING YOU NOW:1 COLIN KAEPERNICK’S COLLUSION SUIT AGAINST THE NFL I. YOU CAN BLOW OUT A CANDLE:2 KAEPERNICK’S PROTEST FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE Colin Kaepernick’s (“Kaepernick”) silent protest did not flicker into existence out of nowhere; his issues are ones that have a long history, not just in the United States, but around the world.3 In September 1977, South African police officers who were interro- gating anti-apartheid activist Steven Biko became incensed when Biko, forced to stand for half an hour, decided to sit down.4 Biko’s decision to sit led to a paroxysm of violence at the hands of the police.5 Eventually, the authorities dropped off Biko’s lifeless body at a prison hospital in Pretoria, South Africa.6 Given the likely ef- fect the news of Biko’s death would have on a volatile, racially- charged scene of social unrest, the police colluded amongst them- selves to hide the truth of what had happened in police room 619.7 Biko’s decision to sit, his death, and the police’s collusion to cover 1. -

Information Guide

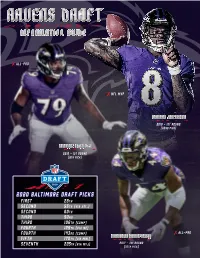

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Regents: Increase Funding

Iowa State Daily, September 2016 Iowa State Daily, 2016 9-9-2016 Iowa State Daily (September 9, 2016) Iowa State Daily Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2016-09 Recommended Citation Iowa State Daily, "Iowa State Daily (September 9, 2016)" (2016). Iowa State Daily, September 2016. 14. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2016-09/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State Daily, 2016 at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State Daily, September 2016 by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Friday, September 9, 2016 | Volume 212 | Number 14 | 40 cents | iowastatedaily.com | An independent student newspaper serving Iowa State since 1890. Iowa State’s new record enrollment: 36,660 By Emily.Barske Thursday. students than any other school state funding, we want to be man Sciences: 4,871; Liberal Arts @iowastatedaily.com The enrollment number is in the world, as well as record sure we are growing at a pace and Sciences: 8,526; Veterinary nearly 2 percent higher than the numbers of non-resident, U.S. that allows us to maintain high Medicine: 749; Interdepartmen- fall 2015 semester, according to multicultural and international quality,” he said. tal Units and Graduate Unde- Iowa State has announced a news release. students,” said President Steven Here’s how the enrollment clared: 404; Post-docs: 307 another record enrollment — “As we work to create a more Leath. breaks down by college: Iowans make up about 57 per- 36,660 for the fall 2016 semester, diverse and inclusive campus, “True to our land-grant mis- Agriculture and Life Sciences: cent of total enrollment, while the eighth straight year of record Iowa State is proud to remain sion, Iowa State is accessible 5,395; Business: 4,772; Design: U.S. -

Jaguars All-Time Roster

JAGUARS ALL-TIME ROSTER (active one or more games on the 53-man roster) Chamblin, Corey CB Tennessee Tech 1999 Fordham, Todd G/OT Florida State 1997-2002 Chanoine, Roger OT Temple 2002 Forney, Kynan G Hawaii 2009 — A — Charlton, Ike CB Virginia Tech 2002 Forsett, Justin RB California 2013 Adams, Blue CB Cincinnati 2003 Chase, Martin DT Oklahoma 2005 Franklin, Brad CB Louisiana-Lafayette 2003 Akbar, Hakim LB Washington 2003 Cheever, Michael C Georgia Tech 1996-98 Franklin, Stephen LB Southern Illinois 2011 Alexander, Dan RB/FB Nebraska 2002 Chick, John DE Utah State 2011-12 Frase, Paul DE/DT Syracuse 1995-96 Alexander, Eric LB Louisiana State 2010 Christopherson, Ryan FB Wyoming 1995-96 Freeman, Eddie DL Alabama-Birmingham 2004 Alexander, Gerald S Boise State 2009-10 Chung, Eugene G Virginia Tech 1995 Fuamatu-Ma’afala, Chris RB Utah 2003-04 Alexis, Rich RB Washington 2005-06 Clark, Danny LB Illinois 2000-03 Fudge, Jamaal S Clemson 2006-07 Allen, David RB/KR Kansas State 2003-04 Clark, Reggie LB North Carolina 1995-96 Furrer, Will QB Virginia Tech 1998 Allen, Russell LB San Diego State 2009-13 Clark, Vinnie CB Ohio State 1995-96 Alualu, Tyson DT California 2010-13 Clemons, Toney WR Colorado 2012 — G — Anderson, Curtis CB Pittsburgh 1997 Cloherty, Colin TE Brown 2011-12 Gabbert, Blaine QB Missouri 2011-13 Anger, Bryan P California 2012-13 Cobb, Reggie* RB Tennessee 1995 Gardner, Isaiah CB Maryland 2008 Angulo, Richard TE W. New Mexico 2007-08 Coe, Michael DB Alabama State 2009-10 Garrard, David QB East Carolina 2002-10 Armour, JoJuan S Miami -

Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2020 Season History/Results Year-By-Year Stats Postseason Records Honors P Denver Broncos Ostseason G Ame

Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2020 Season History/Results Year-by-Year Stats DENVER BRONCOS OSTSEASON AME UMMARIES S P G Postseason 481 Records Honors Miscellaneous DENVER BRONCOS Denver 24, Carolina 10 Sunday, Feb. 7, 2016 • 3:39 p.m. PST • Levi’s Stadium • Santa Clara, Calif. Miscellaneous WEATHER: Sunny, 76º, Wind NW 16 mph • TIME: 3:43 • ATTENDANCE: 71,088 Super Bowl 50 DENVER BRONCOS Behind a ruthless defense led by MVP Von Miller and his 2.5- sack, two-forced fumble performance, the Denver Broncos claimed OFFENSE DEFENSE their third world championship by beating the Carolina Panthers WR 88 D. Thomas DE 95 D. Wolfe 24-10 in Super Bowl 50 at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, Calif. LT 68 R. Harris NT 92 S. Williams At age 39, quarterback Peyton Manning became the oldest start- ing quarterback to win a Super Bowl and the first in NFL history to LG 69 E. Mathis DE 97 M. Jackson win a Super Bowl with two different teams. The Super Bowl 50 vic- C 61 M. Paradis SLB 58 V. Miller Records Honors tory also gave Manning his 200th career win, passing Hall of Famer RG 65 L. Vasquez WLB 94 D. Ware Brett Favre for the most combined victories in league history. RT 79 M. Schofield ILB 54 B. Marshall John Elway, the architect of Denver’s World Championship TE 81 O. Daniels ILB 59 D. Trevathan team, earned his third Super Bowl win and his first as an executive. Gary Kubiak, in his initial season leading the Broncos, also made WR 10 E. -

Oakland Raiders 1

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: Hand Signed Sports Memorabilia California Angels 1. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels Jersey 7 No Hitters PSA/DNA (BWU001IS) $439 2. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels 16x20 Photo SI & Ryan Holo (BWU001IS) $210 3. Nolan Ryan California Angels & Amos Otis Kansas City Royals Autographed 8x10 Photo -Pitching- (BWU001EPA) $172 4. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001EPA) $124 5. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $304 6. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001EPA) $148 7. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001EPA) $176 8. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $280 9. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001EPA) $148 L.A. Dodgers 1. Fernando Valenzuela Signed Dodgers Jersey (BWU001IS) $300 2. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Baseball (BWU001EPA) $232 3. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $388 4. Duke Snider signed baseball (BWU001IS) $200 5. Tommy Lasorda signed jersey dodgers (BWU001IS) $325 6. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors.