Copyright by Taylor Alsop Peterson 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Race Over the Years

P1 THE DAILY TEXAN LITTLE Serving the University of Texas at Austin community since 1900 DITTY Musician moves from ON THE WEB California to pursue a BAREFOOT MARCH passion for jingles Austinites and students walk shoeless to A video explores the meaning of ‘traditional the Capitol to benefit poor children values’ with regard to current legislation LIFE&ARTS PAGE 10 NEWS PAGE 5 @dailytexanonline.com >> Breaking news, blogs and more: dailytexanonline.com @thedailytexan facebook.com/dailytexan Wednesday, April 6, 2011 TEXAS RELAYS TODAY Calendar Monster’s Ball Lady Gaga will be performing at the Frank Erwin Center at 8 p.m. Tickets range from $51.50-$177. Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Track and field teams will compete in the first day of the 84th Annual Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays at the Mike A. Myers Stadium. Texas Men’s Tennis Longhorns play Baylor at the Penick-Allison Tennis Center at 6 p.m. ‘Pauline and Felder | Daily Texan Staff file photo Paulette’ Texas’ Charlie Parker stretches for the tape to finish first in the 100-yard dash to remain undefeated on the season during the 1947 Texas Relays. Today marks the beginning of the The Belgian comedy-drama invitational’s 84th year in Austin. Collegiate and high school athletes will compete in the events, as well as several professional athletes. directed by Lieven Debrauwer will be shown in the Mezes Basement Bo.306 at 6:30 p.m. ‘Take Back the A race over the years Night’ By Julie Thompson Voices Against Violence will hold a rally to speak out against he Texas Relays started as a small, annually to the local economy. -

Central Texas Annual Festivals Festive Art, Music, Food and Cultural Events Where You Can Count on a Good Time Year After Year Celtic Cultural Center Presents: St

Central Texas Annual festivals Festive Art, Music, Food and Cultural Events where You Can Count on a good time Year After Year Celtic Cultural Center Presents: St. Patrick’s Day Austin Fiesta Gardens A fierce Irish tradition and fun for the whole family. Live traditional music, Irish dancing and presentations, games and other cultural activities. http://www.stpatricksdayaustin.com/ APRIL Urban Music Festival Auditorium Shores Urban Music Festival is a family-centric festival for R&B, jazz, funk and reggae music lovers, where national and local entertainment take center stage. http://urbanmusicfest.com/ Louisiana Swamp Thing & Crawfish Festival The Austin American Statesman parking lot It’s a Cajun festival in Texas! Loads of crawfish are consumed at this annual event, which features zydeco, brass band, funk, blues and rock music. http://www.roadwayevents.com/event/ Art City Austin Palmer Events Center FEBRUARY Nearly 200 national artists, top local restaurants, multiple music stages Carnaval Brasileiro and hands-on art activities make this one of the city’s favorite festivals. Palmer Events Center https://www.artallianceaustin.org/ Flamboyant costumes, Brazilian samba music and the uninhibited, spirited atmosphere make Austin’s Carnaval one of the biggest and Old Settler’s Music Festival best festivals of it’s kind outside of Brazil. http://sambaparty.com/ Salt Lick Pavilion and Camp Ben McCulloch Americana, roots rock, blues and bluegrass are performed at this Chinese New Year Celebration signature Central Texas music festival. Arts & crafts, camping, food and Chinatown Center local libations complete this down-home event. Chinese New Year starts on January 28, marking the Lunar New Year. -

1 Is Austin Still Austin?

1 IS AUSTIN STILL AUSTIN? A CULTURAL ANALYSIS THROUGH SOUND John Stevens (TC 660H or TC 359T) Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 13, 2020 __________________________________________ Thomas Palaima Department of Classics Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Richard Brennes Athletics Second Reader 2 Abstract Author: John Stevens Title: Is Austin Still Austin? A Cultural Analysis Through Sound Supervisors: Thomas Palaima, Ph. D and Richard Brennes For the second half of the 20th century, Austin, Texas was defined by its culture and unique personality. The traits that defined the city ushered in a progressive community that was seldom found in the South. In the 1960s, much of the new and young demographic chose music as the medium to share ideas and find community. The following decades saw Austin become a mecca for live music. Austin’s changing culture became defined by the music heard in the plethora of music venues that graced the city streets. As the city recruited technology companies and developed its downtown, live music suffered. People from all over the world have moved to Austin, in part because of the unique culture and live music. The mass-migration these individuals took part in led to the downfall of the music industry in Austin. This thesis will explore the rise of music in Austin, its direct ties with culture, and the eventual loss of culture. I aim for the reader to finish this thesis and think about what direction we want the city to go in. 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisor Professor Thomas Palaima and second-reader Richard Brennes for the support and valuable contributions to my research. -

Oakhurst Townhomes 8507 Kromer Street | Austin, TX 78757

Oakhurst Townhomes 8507 Kromer Street | Austin, TX 78757 OFFERING SUMMARY Total Total Market Total Effective Effective Market Market Unit Type No. of Units Rentable SF Effective Rent Rentable SF Rent/SF Rent/SF Rent/Unit Rent Rent/Unit Potential 2 BR/1 BA 10 850 8,500 $997 $1.17 $9,972 $1,050 $1.24 $10,500 2 BR/1.5 BA 1 925 925 $1,000 $1.08 $1,000 $1,125 $1.22 $1,125 2 BR/2 BA 1 850 850 $1,025 $1.21 $1,025 $1,100 $1.29 $1,100 Totals/ Wtd. Avgs. 12 856 10,275 $1,000 $1.17 $11,997 $1,060 $1.24 $12,725 Value-Add, Townhome Opportunity Oakhurst contains 12 two-bedroom townhomes with substantial rental upside through unit enhancement. The property offers residents spacious homes each equipped with large living areas and kitchen spaces, private backyards or upstairs balconies, large bedrooms with large closets and an on-site card-operated laundry facility. Major Capex Items Recently Completed Current ownership has recently invested heavily in major capex items and infrastructure. Last year, the property’s main water supply and sewer lines were completely replaced as well as five of the HVAC package units. In the past several years, ownership replaced all electrical circuit breaker panels (25 total) and installed a new roof that comes with a transferable warranty (5-year labor/30-year manufacturer). Booming North Austin Submarket Oakhurst Townhomes are located in north central Austin, one of the highest growing submarkets in the city. Major nearby projects like The Domain and Mueller as well as significant development along the Burnet and North Lamar corridors have driven substantial growth in rental rates and home values. -

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

Nominees & Winners for the 86Th Oscars (Feb 2014)

Nominees & Winners for the 86th Oscars® (Feb 2014) The Act of Killing Final Cut for Real Production (Drafthouse Films) • Documentary Feature All Is Lost Black Bear Pictures, Treehouse Pictures, FilmNation Entertainment, Sudden Storm Entertainment, Before The Door/Washington Square Films Production (Lionsgate & Roadside Attractions) • Sound Editing American Hustle Columbia Pictures and Annapurna Pictures Production (Sony Pictures Releasing) • Christian Bale - Actor in a Leading Role • Bradley Cooper - Actor in a Supporting Role • Amy Adams - Actress in a Leading Role • Jennifer Lawrence - Actress in a Supporting Role • Costume Design • Directing • Film Editing • Best Picture • Production Design • Original Screenplay Aquel No Era Yo (That Wasn't Me) Producciones Africanauan Production (FREAK Independent Film Agency) • Live Action Short Film August: Osage County Weinstein Company/Jean Doumanian Productions/Smokehouse Pictures/Battle Mountain Films/Yucaipa Films Production (The Weinstein Company) • Meryl Streep - Actress in a Leading Role • Julia Roberts - Actress in a Supporting Role Avant Que De Tout Perdre (Just before Losing Everything) KG Production • Live Action Short Film Before Midnight Faliro House Production (Sony Pictures Classics) • Adapted Screenplay Blue Jasmine Perdido Production (Sony Pictures Classics) • Cate Blanchett - Actress in a Leading Role • Sally Hawkins - Actress in a Supporting Role • Original Screenplay The Book Thief Fox 2000 Pictures Production (20th Century Fox) • Original Score The Broken Circle Breakdown Menuet -

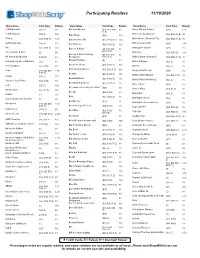

Participating Retailers 11/18/2020

Participating Retailers 11/18/2020 Store Name Card Type Rebate Store Name Card Type Rebate Store Name Card Type Rebate 1-800-Baskets ($50, E) 12% Bahama Breeze ($10, $25, $100, 8% Bravo Cucina Italiana ($25) 12% R, E) 1-800-Flowers ($50, E) 12% Brenner's Steakhouse ($25, $100, R, E) 9% Baja Fresh ($25) 10% 76 Gas ($25, $100, R) 1.5% Brick House Tavern & Tap ($25, $100, R, E) 9% Banana Republic ($25, $100, R, E) 14% 99 Restaurants ($25, E) 13% Brio Tuscan Grille ($25) 12% Bar Ramone ($25, $100, E) 12% Aba ($25, $100, E) 12% Bruegger's Bagels ($10) 7% Barnes & Noble ($5, $10, $25, 8% $100, R, E) Abercrombie & Fitch (E) 5% Bub City ($25, $100, E) 12% Barnes & Noble College ($5, $10, $25, 8% AC Hotels by Marriott ($100, E) 6% Bookstores $100, R, E) Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. ($25, $100, R, E) 9% Baskin-Robbins (E) 2% Academy Sports + Outdoors ($25) 4% Buca di Beppo ($25, E) 8% Bass Pro Shops ($25, $100, E) 10% Ace Hardware ($25, $100) 4% Buckle ($25, E) 8% Bath & Body Works ($10, $25, R, E) 12% Acme ($10, $25, $50, 4-6% Budget Car Rental ($50) 8% $100, R) Beatrix ($25, $100, E) 12% Buffalo Wild Wings® ($10, $25, R, E) 8% adidas ($25, E) 13% Beatrix Market ($25, $100, E) 12% Build-A-Bear Workshop ($25, E) 8% Advance Auto Parts ($25, $100) 7% Bed Bath & Beyond ($25, $100, E) 7% Buona Beef ($10) 8% aerie ($25, E) 10% Beechwood Inn & Coyote Cafe' ($25) 5% Burger King ($10, R*, E) 4% Aeropostale ($25, R*, E) 10% Bel-Air ($25, $100) 4% Burlington ($25, E) 8% Airbnb (E) 5% Belk ($25, $100, E) 8% Burlington Shoes ($25) 8% Alamo Drafthouse Cinema (E) 8% -

Switchblade Comb" by Mobius Vanchocstraw

00:00:00 Music Music "Switchblade Comb" by Mobius VanChocStraw. A jaunty, jazzy tune reminiscent of the opening theme of a movie. Music continues at a lower volume as April introduces herself and her guest, and then it fades out. 00:00:08 April Wolfe Host Welcome to Switchblade Sisters, where women get together to slice and dice our favorite action and genre films. I'm April Wolfe. Every week, I invite a new female filmmaker on—a writer, director, actor, or producer—and we talk in-depth about one of their fave genre films, perhaps one that influenced their own work in some small way, and today I'm very excited to have writer-director Alice Waddington here with me. Hi, Alice! 00:00:28 Alice Guest Hi, April! How are you? Waddington [Music fades out.] 00:00:30 April Host Oh, I'm quite well. [Alice laughs.] Despite fires raging. 00:00:32 Alice Guest Oh my goodness. 00:00:33 April Host But I gotta say your pink jumpsuit—pink corduroy jumpsuit is really livening up the place. 00:00:39 Alice Guest [Laughs.] Thank you so much. I'm—you know, I am on my Logan's Run stuff already. So. [Laughs.] 00:00:44 April Host Absolutely. I mean, Halloween should be year-round. [Alice laughs.] Okay, so for those of you who are not as familiar with Alice's work, please let me give you an introduction. Alice Waddington was born in a rural background, but she was raised in the big city of Bilbao, Spain. -

Issue #72 Summer / Fall 2008 Lars Bloch Interview (Part 2) a Man, a Colt the MGM Rolling Road Show Latest DVD Reviews

Issue #72 Summer / Fall 2008 Lars Bloch Interview (part 2) A Man, a Colt The MGM Rolling Road Show Latest DVD Reviews WAI! #72 THE SWINGIN’ DOORS April and May were months that took a number of well known actors of the Spaghetti western genre: Jacques Berthier, Robert Hundar, John Phillip Law and Tano Cimarosa were all well known names in the genre. Of course we should expect as much since these people are now well into their 70s and even 80s. Still in our minds they are young vibrant actors who we see over and over again on video and DVD. It’s hard to realize that it’s been 40+ years since Sergio Leone kicked off the Spaghetti western craze and launched a world wide revolution in film that we still see influencing films today. Hard to believe Clint Eastwood turned 78 on May 30th. Seems like only yesterday he was the ‘Man with No Name’ and starring in the first of the Leone films that launched the genre. Remember when Clint was criticized so badly as an actor and for the films he appeared in during the 60s and 70s. Now he’s revered in Hollywood because he’s outlived his critics. I guess we recognized a real star long before the critics did. A great idea came to Tim League’s mind in the launching of the “Rolling Road Show”, where films are actually shown where they were filmed. I wasn’t able to travel to Spain to see the Dollars trilogy but we have a nice review of the films and the experience by someone who was there. -

Copyrighted Material

c01.qxd 2/28/05 1:39 PM Page 7 1 The Personal Media Revolution ROWING UP IN A FLYSPECK TOWN IN SOUTHERN MISSIS- sippi in the early 1980s, ten-year-old Chris Strompolos Gstared out his bedroom window and dreamed. He fanta- sized about what it would be like for a whiff of adventure to breeze through his humdrum little burg. On a sticky June afternoon in 1981 he found a vehicle for his wanderlust in the darkness of a local movie theater. He watched, jawCOPYRIGHTED agape, as Harrison Ford outran MATERIAL a rolling boulder, dodged a swarm of blow darts, and dangled over a pit of slithering snakes in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Chris Strompolos was blown away. The movie captured his imagination like nothing he had ever encountered. He thought, I want to do that. And so he did. Chris first mentioned his outlandish idea to an older kid, Eric Zala, a seventh-grader at their school in Gulfport. Chris did not suggest a quick 7 c01.qxd 2/28/05 1:39 PM Page 8 8 ❘ DARKNET and easy backyard tribute to Raiders that they could pull off on a summer weekend. Oh, no. He proposed shooting a scene-by-scene re-creation of the entire movie. He wanted to create a pull-out-all-the-stops remake of Steven Spielberg’s instant blockbuster, which was filmed on a $20 million budget and made $242 million in U.S. movie theaters. Chris and Eric agreed they would have to cut a few corners, given their somewhat more modest savings account, but, yes, of course they could do it! Eric, a budding cartoonist, began sketching out costumes for each of the characters. -

• Onion Creek Club

Summary of 2018 Sponsors/Contributors (5/9/2018) Following is a listing of Sponsors and Contributors who have donated to the 30th Annual American Legion Memorial Golf Tournament which will be conducted on May 10, 2018 at the Onion Creek Club, Austin, TX. A Sponsor is a donor of cash and a Contributor is a donor of goods and/or services equated to a cash value (e.g. Live/Silent Auction items, Door Prize items, “Goodies" Bag items, General Support items such as Players Handbooks, Brochures etc.). The money we raise will be used to support a variety of veterans and community projects including Veterans Scholarships, Scholarships for High School Students, Fisher House, Homeless Veterans, American Legion Boys/Girls State and others as determined by the Post Executive Committee. Sponsors - Cash Presenting/Host Sponsor Apptronik Onion Creek Club Intrepid – Ace Fire Equipment Intrepid - Texican Café Corporate Sponsors ($1,500 or More) TLG Contractor Services Austin Roofing and Construction Unlimited Ltd. H-E-B Velocity Credit Union Howdy Honda K.W. Gutshall & Associates / Lincoln Silver Sponsors ($300 or More) Investment Austin Eyecare United Heritage Charity Foundation Capital Energy Company Walmart #1253 (Ben White) Bob & Mary Jane Caudill Walmart #4219 (Buda) Jim & Nancy Corcoran Dog Camp Platinum Sponsors ($1,000) Roland & Karen Greenwade Sam’s Club #8259 (Southpark) Tony & Sue Nuccio Jim and Phyllis Stolp Angie Sakalay Virgil & LaFern Swift Velocity Credit Union Bronze Sponsors ($100 or More) Walmart #4554 (Anderson -

88Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Natalie Kojen [email protected] January 14, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 88TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, Guillermo del Toro, John Krasinski and Ang Lee announced the 88th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 14). Del Toro and Lee announced the nominees in 11 categories at 5:30 a.m. PT, followed by Boone Isaacs and Krasinski for the remaining 13 categories at 5:38 a.m. PT, at the live news conference attended by more than 400 international media representatives. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars® website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Official screenings of all motion pictures with one or more nominations will begin for members on Saturday, January 23, at the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theater. Screenings also will be held at the Academy’s Linwood Dunn Theater in Hollywood and in London, New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 88th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 28, 2016, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live by the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m.