Download Case Study of Udaipur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transferring Spending Power to the Poorest Part 1

Cashrelief: A Pilot by Agrani India Foundation Transferring Spending Power to the Poorest Part 1: Underlying Conditions Laveesh Bhandari & Aishwarya Chordiya* Abstract Cashrelief.org (an initiative of Agrani India Foundation) transfers benefits directly to the underprivileged through monetary transfers. It recently conducted such an exercise where an amount close to two years average household income was unconditionally transferred to all the 34 households of a hamlet. This is the first of a three-part series that detail the identification, implementation, and outcomes of the intervention in a tribal hamlet of Udaipur. The oldest working woman in every household of the hamlet was unconditionally transferred close to INR one lakh. The aim of this study is to better understand how such a substantial and unconditional transfer of spending power plays out and whether it translates into long term economic, social and psychological benefits to the women and their families. 1. Project Objectives and Expectations Poverty continues to be a global issue, affecting millions worldwide. Naturally then, its alleviation efforts attract attention, resources and efforts of not only governments but also international organisations, civil societies and even the academia. Changing times and better information have led to myriad approaches and strategies, with the end goal being the same. Even after all these efforts and resources, the gap remains wide, with the most marginal remaining the worst hit and endlessly living in vulnerability and suffering on the ugly side of inequality. Governments across countries have been able to develop or adapt their social security nets to reduce economic insecurity with varying levels of success. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the Meet

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the meeting of the Project Approval Board held on 14th June, 2018 to consider the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 of Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan. 1. INTRODUCTION The meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) for considering the Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 under Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan was held on 14-06-2018. The list of participants who attended the meeting is attached at Annexure-I. Sh Maneesh Garg, Joint Secretary (SE&L) welcomed the participants and the State representatives led by Shri Naresh Pal Gangwar, Secretary (Education), Government of Rajasthan and invited them to share some of the initiatives undertaken by the State. 2. INITIATIVES OF THE STATE Adarsh and Utkrisht Vidyalaya Yojana: An Adarsh Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-XII) has been developed in each Gram Panchayat as center of excellence. An Utkrisht Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-VIII) has also been developed in each Gram Panchayat under the mentorship of Adarsh school to ensure quality school coverage for other villages in the Gram Panchayat. Panchayat Elementary Education Officer- Principals of Adarsh school have been designated as ex-officio Panchayat Elementary Education Officer (PEEO) to provide leadership and mentorship to all other government elementary schools in the Gram Panchayat. These PEEOs have been designated as Cluster Resource Centre Facilitator (CRCF) for effective monitoring. Integration of Anganwadi centers with schools- Around 38000 Anganwadi centers have been integrated with schools having primary sections for improving pre-primary education under ECCE program of ICDS. -

Sno Tehsil Village Khasra Area Soilclass Holder Landuse Latitute Longitute Remark

1 URBAN IMPROVEMENT TRUST, UDAIPUR LAND BANK KHASRA REPORT sno Tehsil Village Khasra Area SoilClass Holder Landuse Latitute Longitute remark 1 Badgaon Amberi 4 53.600835 Ka Gorama UIT Plantation 73° 43' 56.378" E 24° 40' 38.361" N From Bilanaam 2 Badgaon Amberi 9 10.421368 Pahad UIT Forest 73° 44' 11.832" E 24° 40' 25.348" N From Bilanaam 3 Badgaon Amberi 20 1.984697 Kankri Makaan UIT Plantation 73° 44' 29.440" E 24° 40' 24.033" N From Bilanaam Bhoomi Kankri 4 Badgaon Amberi 31 1.15133 UIT Plantation 73° 44' 39.660" E 24° 40' 21.549" N From Bilanaam Kadeem Bhoori Kankri 5 Badgaon Amberi 43 8.735091 UIT Forest 73° 44' 52.534" E 24° 40' 17.196" N From Bilanaam Gorma Bhoori Kankri 6 Badgaon Amberi 260 6.049624 UIT Residential 73° 44' 11.743" E 24° 40' 1.559" N From Bilanaam Gorma 7 Badgaon Amberi 414 1.872481 Badda UIT Residential 73° 44' 13.100" E 24° 39' 45.608" N From Bilanaam 8 Badgaon Amberi 437 53.668356 Kankri Kadeem UIT 73° 44' 46.918" E 24° 39' 41.939" N From Bilanaam Residential 9 Badgaon Amberi 438 53.668356 Pahad Charagaah 73° 44' 46.918" E 24° 39' 41.939" N Plantation 10 Badgaon Amberi 508 2.70538 Pahad UIT Residential 73° 44' 37.381" E 24° 39' 37.299" N From Bilanaam 11 Badgaon Amberi 512 2.455649 Pahad UIT Residential 73° 44' 34.344" E 24° 39' 30.920" N From Bilanaam 12 Badgaon Amberi 518 1.689911 Pahad UIT Residential 73° 44' 32.671" E 24° 39' 26.461" N From Bilanaam 13 Badgaon Amberi 633 2.065059 Magri UIT Residential 73° 44' 16.556" E 24° 39' 29.076" N From Bilanaam 14 Badgaon Amberi 689 1.477009 Magri UIT Residential 73° -

District Boundary Assembly Constituency

NEW ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES (Based on Rajasthan Gazette Notification SADULSHAHAR-1 Dated 25th January, 2006) GANGANAGAR-2 SANGARIA-7 KARANPUR-3 RAJASTHAN PILIBANGA (SC)-9 HANUMANGARH- 8 GANGANAGAR RAISINGHNAGAR (SC)-5 SURATGARH-4 HANUMANGARH BHADRA-11 NOHAR-10 ® ANUPGARH (SC)-6 TARANAGAR-20 LUNKARANSAR-16 SADULPUR-19 KHAJUWALA SARDARSHAHAR-21 (SC)-12 CHURU PILANI CHURU-22 (SC)-25 BIKANER MANDAWA-28 SURAJGARH-26 JHUNJHUNUN-27 TIJARA-59 JHUNJHUNUN DUNGARGARH-17 BIKANER FATEHPUR-32 WEST-13 KHETRI-31 BEHROR- BIKANER RATANGARH-23 EAST-14 NAWALGARH- 62 MUNDAWAR- 61 29 KISHANGARH KOLAYAT-15 UDAIPURWATI- BAS-60 LACHHMANGARH-33 30 NEEM KA THANA-38 KAMAN-70 SUJANGARH KOTPUTLI-40 (SC)-24 SIKAR-35 BANSUR-63 KHANDELA-37 ALWAR LADNUN- URBAN-66 RAMGARH-67 NOKHA-18 106 DHOD (SC)-34 SIKAR SRIMADHOPUR-39 ALWAR NAGAR-71 ALWAR VIRATNAGAR-41 RURAL (SC)-65 DEEG - DANTA KUMHER-72 RAMGARH-36 KATHUMAR DEEDWANA-107 SHAHPURA-42 PHALODI-122 (SC)-69 JAYAL RAJGARH - (SC)-108 BHARATPUR- NAGAUR- CHOMU-43 THANAGAZI-64 LAXMANGARH (ST)-68 73 109 NADBAI-74 NAWAN- JAISALMER- 115 JAMWA BHARATPUR 132 AMBER-47 MAHUWA-86 NAGAUR MAKRANA- RAMGARH BANDIKUI-85 WEIR 113 (ST)-48 (SC)-75 JAISALMER KHINVSAR-110 JHOTWARA-46 JAIPUR DAUSA- LOHAWAT-123 BAYANA POKARAN- ADARSH 88 NAGAR-53 DAUSA (SC)-76 133 PHULERA-44 SIKRAI RAJAKHERA-80 DEGANA- (SC)-87 HINDAUN 112 PARBATSAR- BASSI (SC)-82 BAGRU 114 (ST)-57 PUSHKAR- (SC)-56 TODABHIM DHOLPUR- JODHPUR 99 (ST)-81 DHAULPUR 79 OSIAN- DUDU BARI-78 125 (SC)-45 CHAKSU KARAULI-83 MERTA (SC)-58 LALSOT BAMANWAS BASERI BHOPALGARH (SC)-111 (ST)-89 (SC)-126 -

Final Electoral Roll / Voter List (Alphabetical), Election - 2018

THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL / VOTER LIST (ALPHABETICAL), ELECTION - 2018 [As per order dt. 14.12.2017 as well as orders dt.23.08.2017 & 24.11.2017 Passed by Hon'ble Supreme Court of India in Transfer case (Civil) No. 126/2015 Ajayinder Sangwan & Ors. V/s Bar Council of Delhi and BCI Rules.] AT UDAIPUR IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP LOCATION OF POLLING STATION :- BAR ROOM, JUDICIAL COURTS, UDAIPUR DATE 01/01/2018 Page 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Electoral Name as on the Roll Electoral Name as on the Roll Number Number ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ ' A ' 77718 SH.AADEP SINGH SETHI 78336 KUM.AARTI TAILOR 67722 SH.AASHISH KUMAWAT 26226 SH.ABDUL ALEEM KHAN 21538 SH.ABDUL HANIF 76527 KUM.ABHA CHOUDHARY 35919 SMT.ABHA SHARMA 45076 SH.ABHAY JAIN 52821 SH.ABHAY KUMAR SHARMA 67363 SH.ABHIMANYU MEGHWAL 68669 SH.ABHIMANYU SHARMA 56756 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH 68333 SH.ABHIMANYU SINGH CHOUHAN 64349 SH.ABHINAV DWIVEDI 74914 SH.ABHISHEK KOTHARI 67322 SH.ABHISHEK PURI GOSWAMI 45047 SMT.ADITI MENARIA 60704 SH.ADITYA KHANDELWAL 67164 KUM.AISHVARYA PUJARI 77261 KUM.AJAB PARVEEN BOHRA 78721 SH.AJAY ACHARYA 76562 SH.AJAY AMETA 40802 SH.AJAY CHANDRA JAIN 18210 SH.AJAY CHOUBISA 64072 SH.AJAY KUMAR BHANDARI 49120 SH.AJAY KUMAR VYAS 35609 SH.AJAY SINGH HADA 75374 SH.AJAYPAL -

City Development Plan for Udaipur, 2041

City Development Plan for Udaipur, 2041 (Interim City Development Plan) June 2014 Supported under Capacity Building for Urban Development project (CBUD) A Joint Partnership Program between Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India and The World Bank CRISIL Risk and Infrastructure Solutions Limited Ministry of Urban Development Capacity Building for Urban Development Project City Development Plan for Udaipur – 2041 Interim City Development Plan June 2014 Green Lake city of India... Education hub … Hospitality centre…. Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank BMTPC Building Materials and Technology Promotion Council BOD Biochemical oxygen demand BPL Below Poverty line BRG Backward Regional Grant BRGF Backward Regional Grant Fund CAA Constitutional Amendment Act CAGR Compound Annual Growth Rate CAZRI Central Arid Zone Research Institute CBUD Capacity Building for Urban Development CCAR Climate Change Agenda for Rajasthan CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CST Central Sales Tax DDMA District Disaster Management Authority DEAS Double entry accounting system DLC District land price committee DPR Detailed Project Report DRR Disaster risk reduction EWS Economically weaker section GDDP Gross District Domestic Product GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green House Gases GIS Geo information system HRD Human Resource Development IHSDP Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme IIM Indian Institute of Management INCCA Indian Network for Climate Change Assessment LOS Level of Services MLD Million Liter per Day NLCP National Lake Conservation -

Udaipur MO.Pdf

Name of S.No Name of Trainee Designation Place Of Posting Mobile No. Period of Training Training PHC Nayagaon, Dr. Ram Bharat M.O. 8107762202 19-21-Apr-11 1 Udaipur CHC Kherwara, Dr. Satish Joharwal M.O. 9649918858 19-21-Apr-11 2 Udaipur Dr. Kamlesh Kumar PHC Jawas, M.O. 9784973530 19-21-Apr-11 3 Sharma Udaipur PHC Pahada, Dr. Lalit Dilwaliya M.O. 9828833808 19-21-Apr-11 4 Udaipur Dr. Kailash Chand PHC Bawalwada, M.O. 8058235817 26-28-Apr-11 5 Meena Udaipur Dr. Neeraj Kumar CHC Kherwada, M.O. 9636607504 26-28-Apr-11 6 Nagar Udaipur PHC Chhani, Dr. Murlidhar M.O. 9680190162 26-28-Apr-11 7 Udaipur PHC Bedla, Dr. Sharad Nalwaya M.O. 9414741076 17-19-May-11 8 Udaipur Routine Immunization Immunization Routine Dr. Shekhar Suman PHC Padedi, M.O. 7742414313 17-19-May-11 9 Saxena Udaipur 10 Dr. Rajendra Lamror M.O. PHC Pai, Udaipur 7742363054 24-26-May-11 PHC Barapal, Dr. Akshay Kavdia M.O. 9829506428 24-26-May-11 11 Udaipur PHC Menar, Dr. Tanuj Dave M.O. 9413954768 14-16-Jun-11 12 Udaipur PHC Khemali, Dr. Anamika Damor M.O. 9828332752 14-16-Jun-11 13 Udaipur PHC Dewali, Dr. Hemant Dama M.O. (Goverdhan 9672244351 14-16-Jun-11 14 Villas) Udaipur PHC Dr. Bhagwati M.O. Savinakheda, 9672522305 14-16-Jun-11 Chundawat 15 Udaipur PHC Bikarni, Dr. Mohammad Rafik M.O. 8239681958 14-16-Jun-11 16 Udaipur Dr. Devendra Singh PHC Dabok, M.O. 9414386228 21-23-Jun-11 17 Rao Udaipur CHC Mavli, Dr. -

Name of Gram Panchayat

Name of the Block……… (A) (B) Name of Gram Identified FI Name of Name of allotted name of block Br./BCA/ATM Name and contact Name & designation of Week Names Village Populatio Post Panchayat place/villag allotted bank branch existing or number of BCA Bank Officer identified day(s) of all code as n of the office/su (GP) e proposed with for weekly visits fixed for revenue used in revenue b-Post name of bank visits villages 2011 villages office covered census (2001 by census) 1 2 3 4 4a 4b 4c 5BCAs/ 6 7 8 BC LAXMILAL MEENA Hmeant kumar BM Friday 201 yes Alsigarh Alsigarh Allahabad bank Rampura choraya Girwa 9950263740 Alsigarh 2,960 Pai Pai Allahabad Bank Rampura choraya Girwa BC Suresh kataria 9001370774Hmeant kumar BM Friday Pai 202 3,562 yes Undari BC Hmeant kumar BM Undari yes Undari Kalan Kalan Allahabad Bank Rampura choraya Girwa Bhupendra Chaudhary 9929512904 Friday Kalan 199 2,082 Undari BC Hmeant kumar BM Undari yes Undari Khurd Khurd Allahabad Bank Rampura choraya Girwa Ramesh Meena 8107803454 Friday Khurd 190 2,181 Boojhda Boojhda Allahabad Bank Rampura choraya Girwa BC Mangi lal teli 9829876289Hmeant kumar BM Friday Boojhda 2,136 yes Sisarma Sisarma Allahabad Bank Rampura choraya Girwa BC Pankaj Nagda 9950645505Hmeant kumar BM Friday Sisarma 148 2,802 yes BC Delip rewadiya BM Kanuwar yes Kanuwara Kanuwara Allahabad bank Rishbdeo Kherwara B l Kalasua 9001252635 Friday a 190 2,486 Patia Patia Allahabad Bank Bomtawara Kherwara BC Savita Devi 9587797510 Kumar Amtabh BM Friday Patia 124 2,100 yes Seriya Seriya Allahabad Bank Lakapa -

Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India)

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Tehsil Wise Study and Analysis of Health Centers using GIS (Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India) Kawaljeet Singh1, B. L. Pal2 1M. Tech Scholar, Mewar University, Gangrar, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of CSE, Mewar University, Gangrar, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India Abstract: Healthcare is the birth right of the citizens of any country. Most of the developed countries have implemented universal healthcare systems. However many developing countries like India are striving for the universal healthcare. The objective of WHO (World Health Organization) is to promote and coordinate healthcare across the world. India has been in close relationship with WHO since 1948 and is committed to provide affordable healthcare to the citizens of its country. For India the biggest challenge is the population . Moreover more than 70% people live in rural areas. The access to primary health care in rural area is very limited. In this direction Indian government launched National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) to improve the healthcare services in the rural areas. Rajasthan is among the 18 states of India which was identified by NRHM with very low healthcare. There many government policies and organizations (NGOs) are being run, still there is need to focus a lot on rural health development programs. The healthcare in India comprises of three tiers, Sub Centre (SC), Primary Health Centre (PHC) and Community Health Centre(CHC) . There are various population norms provided by Ministry of Health for the opening of health centers in the rural areas. -

Ajmer Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited

Ajmer Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited Corporate Identification Number (CIN) – U40109RJ2000SGC016482 Registerd Office: Vidyut Bhawan, Panchsheel Nagar, Makarwali Road, Ajmer-305004 e-mail: [email protected] ; Website – www.avvnl.com District / Circle Toll free No. 18001806531 Customer Care Centre, Ajmer 18001806565 Ajmer City Circle/ District Circle 18001806532 Bhilwara 18001806533 Nagaur 18001806534 Jhunjhunu 18001806535 Sikar 18001806536 Chittorgarh 18001806537 Pratapgarh 18001806538 Banswara 18001806539 Dungarpur 18001806540 Rajsamand 18001806541 Udaipur 18001806542 Please select your Circle/ District for viewing the Contact information of Nigam Officers (fuxe vf/kdkfj;ksa ds laidZ tkudkjh ns[kus ds fy, vius ldZy @ftyk p;u djsaA) Ajmer City Circle/ City Ajmer District Circle/ District Bhilwara Circle/ District Nagaur Circle/ District Jhunjhunu Circle/ District Sikar Circle/ District Udaipur Circle/ District Rajsamand Circle/ District Chittorgarh Circle/ District Pratapgarh Circle/ District Dungarpur Circle/ District Banswara Circle/ District RDPPC Wing Accounts Wing Store Wing M&P Wing IT Wing Vigilance Wing Civil Wing Chief Engineer(s) Project Wing Chief Engineer(O&M), Ajmer Chief Engineer(O&M), Jhunjhunu Chief Engineer (O&M), Udaipur Zone Office Zone Office Zone Office Corporate Office Building, AVVNL, Ajmer (Vidhyut Bhawan) Board of Directors Legal Cell Commercial Wing Plan Wing Turnkey Works Wing RGGVY Wing Company Secretary Cell Material Management Wing Administrative Wing Director (Finance) – Personal Cell Director (Technical) – Personal Cell MD Cell/ Office Ajmer Zone Hierarchy (A) SE Ajmer City Circle (B) SE Ajmer Distt. Circle (1) XEN (CD-I), Ajmer (1) XEN (O&M), Kishangarh 1. AEN (CSD-II), Ajmer 1. AEN (O&M), Kishangarh 2. AEN (CSD-III), Ajmer 2. AEN (Rural), Kishangarh 3. AEN (CSD-V), Ajmer 4. -

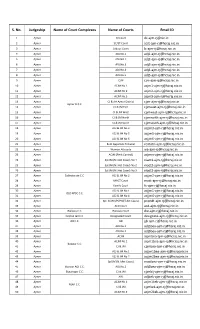

E-Mail Ids of Rajasthan Judiciary

S. No. Judgeship Name of Court Complexes Name of Courts Email ID 1 Ajmer DJ Court [email protected] 2 Ajmer SC/ST Court [email protected] 3 Ajmer Labour Court [email protected] 4 Ajmer ADJ No.1 [email protected] 5 Ajmer ADJ NO.2 [email protected] 6 Ajmer ADJ No.3 [email protected] 7 Ajmer ADJ No.4 [email protected] 8 Ajmer ADJ No.5 [email protected] 9 Ajmer CJM [email protected] 10 Ajmer ACJM No.1 [email protected] 11 Ajmer ACJM No.2 [email protected] 12 Ajmer ACJM No.3 [email protected] 13 Ajmer CJ & JM Ajmer District [email protected] Ajmer D.C.C. 14 Ajmer CJ & JM East [email protected] 15 Ajmer CJ & JM West [email protected] 16 Ajmer CJ & JM North [email protected] 17 Ajmer CJ & JM South [email protected] 18 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.3 [email protected] 19 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.5 [email protected] 20 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.6 [email protected] 21 Ajmer Rent Appellate Tribunal [email protected] 22 Ajmer Women Attrocity [email protected] 23 Ajmer ACJM (Rent Control) [email protected] 24 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.1 [email protected] 25 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.2 [email protected] 26 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.3 [email protected] 27 Ajmer Collectorate C.C.