Android and Competition Law: Exploring and Assessing Google’S Practices in Mobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing App Sideloading Threats on Ios Whitepaper

Whitepaper Enterprise Mobile Security Managing App Sideloading Threats on iOS Whitepaper I. Introduction II. The Path to App Sideloading Through rigorous app review Apple has lowered the risk Signing Certificates of downloading malware from its App Stores to near Apple offers two types of signing certificates for app zero. Companies, however, increasingly rely on an app- distribution outside of their App Stores and both types distribution mechanism called enterprise provisioning allow users to install and execute signed apps on that allows them to distribute apps to employees without non-jailbroken devices: Apple’s review as long as the apps are signed with an Apple-issued enterprise signing certificate. 1) A developer certificate, intended to sign and deploy test apps to a limited number of devices. Unfortunately, attackers have managed to hijack this app-distribution mechanism to sideload apps on 2) An enterprise certificate, intended to sign non-jailbroken devices, as demonstrated in the recent and widely deploy apps to devices within an Wirelurker attack. Organizations today face a real organization. security threat that attackers will continue to abuse To obtain these certificates you must enroll in one of enterprise provisioning and use it to sideload malware, Apple’s two iOS developer programs. Table 1 on the especially since: following page summarizes the enrollment requirements 1) The widespread prevalence of legitimate, for each program and their app provisioning restrictictions. enterprise-provisioned iOS apps in the workplace Both types of signing certificates expire after a year, has conditioned employees to seeing (and ignoring) whereupon developers can apply for new ones. Apple can the security warnings triggered on devices also revoke certificates if it learns of abuse and an app when installing these apps. -

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Nexus S with Google running Android 2.3 "Gingerbread" Company / developer Google Inc., Open Handset Alliance [1] Programmed in C (core), C++ (some third-party libraries), Java (UI) Working state Current [2] Source model Free and open source software (3.0 is currently in closed development) Initial release 21 October 2008 Latest stable release Tablets: [3] 3.0.1 (Honeycomb) Phones: [3] 2.3.3 (Gingerbread) / 24 February 2011 [4] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, Power, x86 Kernel type Monolithic, modified Linux kernel Default user interface Graphical [5] License Apache 2.0, Linux kernel patches are under GPL v2 Official website [www.android.com www.android.com] Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications.[6] [7] Google Inc. purchased the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., in 2005.[8] Android's mobile operating system is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel. Google and other members of the Open Handset Alliance collaborated on Android's development and release.[9] [10] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[11] The Android operating system is the world's best-selling Smartphone platform.[12] [13] Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. There are currently over 150,000 apps available for Android.[14] [15] Android Market is the online app store run by Google, though apps can also be downloaded from third-party sites. -

Compromised Connections

COMPROMISED CONNECTIONS OVERCOMING PRIVACY CHALLENGES OF THE MOBILE INTERNET The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and many other international and regional treaties recognize privacy as a fundamental human right. Privacy A WORLD OF INFORMATION underpins key values such as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and freedom of speech, IN YOUR MOBILE PHONE and it is one of the most important, nuanced and complex fundamental rights of contemporary age. For those of us who care deeply about privacy, safety and security, not only for ourselves but also for our development partners and their missions, we need to think of mobile phones as primary computers As mobile phones have transformed from clunky handheld calling devices to nifty touch-screen rather than just calling devices. We need to keep in mind that, as the storage, functionality, and smartphones loaded with apps and supported by cloud access, the networks these phones rely on capability of mobiles increase, so do the risks to users. have become ubiquitous, ferrying vast amounts of data across invisible spectrums and reaching the Can we address these hidden costs to our digital connections? Fortunately, yes! We recommend: most remote corners of the world. • Adopting device, data, network and application safety measures From a technical point-of-view, today’s phones are actually more like compact mobile computers. They are packed with digital intelligence and capable of processing many of the tasks previously confined -

History and Evolution of the Android OS

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector CHAPTER 1 History and Evolution of the Android OS I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this. —Steve Jobs, Apple Inc. Android, Inc. started with a clear mission by its creators. According to Andy Rubin, one of Android’s founders, Android Inc. was to develop “smarter mobile devices that are more aware of its owner’s location and preferences.” Rubin further stated, “If people are smart, that information starts getting aggregated into consumer products.” The year was 2003 and the location was Palo Alto, California. This was the year Android was born. While Android, Inc. started operations secretly, today the entire world knows about Android. It is no secret that Android is an operating system (OS) for modern day smartphones, tablets, and soon-to-be laptops, but what exactly does that mean? What did Android used to look like? How has it gotten where it is today? All of these questions and more will be answered in this brief chapter. Origins Android first appeared on the technology radar in 2005 when Google, the multibillion- dollar technology company, purchased Android, Inc. At the time, not much was known about Android and what Google intended on doing with it. Information was sparse until 2007, when Google announced the world’s first truly open platform for mobile devices. The First Distribution of Android On November 5, 2007, a press release from the Open Handset Alliance set the stage for the future of the Android platform. -

An Ergonomic Study on Influence of Touch-Screen Phone Size on Single- Hand Operation Performance

MATEC Web of Conferences 40, 009 01 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20164009001 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2016 An Ergonomic Study on Influence of Touch-screen Phone Size on Single- hand Operation Performance Rui Zhu1 , Zhongzhe Li1 1Industrial Design Department Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China Abstract. Touch-screen smart phones have gradually occupied the market of traditional Qwerty Phones and become the mainstream products of mobile phone industry. However, few ergonomics research has been conducted on the touch screens of smart phones, while it has led to tendosynovitis among users owing to the overuse of thumbs. Sizes of smart phones in market range from 3.0 to 7.0 inches. What’s more, 4.0 inches and above are the common size of current touch screens. Also, considering the users’ habits, one-hand operation is preferred when the other hand is occupied. This paper has collected hand parameters of 80 subjects and has adopted an experiment which includes the performance testing and surveys of subjective evaluation by means of usability evaluation. After analysing correlation between touch-screen sizes and operation performances, the result indicates that under one-hand operation, the size of touch screen affects the operation performance significantly. However, it’s hard to implement one-hand operation if the touch-screen size is over 5.7 inches. Additionally, the thickness of smart phones affects the degree of comfort remarkably. 1 Introduction such as tendosynovitis, in a slow process which cannot be observed easily. Nowadays, touch-screen technologies have been widely adopted in mobile phone industry and smart phones with touch screens have become the focus of commercial competitions among mobile phones manufacturers. -

Developer Bootstrap: Good Control Essentials

Developer Bootstrap: Good Control Essentials Last updated: Wednesday, December 21, 2016 ©2016 BlackBerry Limited. Trademarks, including but not limited to BLACKBERRY, BBM, BES, EMBLEM Design, ATHOC, MOVIRTU and SECUSMART are the trademarks or registered trademarks of BlackBerry Limited, its subsidiaries and/or affiliates, used under license, and the exclusive rights to such trademarks are expressly reserved. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. This documentation is provided "as is" and without condition, endorsement, guarantee, representation or warranty, or liability of any kind by BlackBerry Limited and its affiliated companies, all of which are expressly disclaimed to the maximum extent permitted by applicable law in your jurisdiction. 2 Developer Bootsrap: Good Control Contents Revision history 5 Introduction 6 Background and assumptions 6 Activating Your First GD Application 6 To set up your first GD application and prepare for activation 6 To set up the user's device 7 Add Users 7 Adding A Single User Account via Active Directory 7 Import Users by AD Group 8 Adding Multiple User Accounts via Active Directory 8 Adding User Accounts 9 Importing Multiple User Accounts from CSV File 10 CSV Record Layout and Limits 10 Import Process 11 Possible Error Messages 11 Adding applications 13 Adding a custom application 13 Adding BlackBerry Dynamics app IDand version only 13 Specifying app servers 14 Adding new BlackBerry Dynamics entitlement versions (BlackBerry Dynamics app versions) 14 Entitling end-users to applications or denying them 15 Sequence of app version entitling and denying: entitle, then deny 15 Activating an Application for a User 15 Action by the User 16 3 BlackBerry Dynamics documentation 17 4 Revision history Revision history Date Description 2016-12-19 Version numbers updated for latest release; no content changes. -

Essential Phone on Its Way to Early Adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, the Mercury News

Essential Phone on its way to early adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, The Mercury News this week in a press briefing in Essential's headquarters in Palo Alto. "People have neglected hardware for years, decades. The rest of the venture business is focused on software, on service." Essential wanted to make a timeless, high-powered phone, according to Rubin. Its bezel-less and logo- less design is reinforced by titanium parts, stronger than the industry standard aluminum parts, and a ceramic exterior. It has no buttons in its front display but has a fingerprint scanner on the back. The company is also making accessories, like an attachable 360-degree camera, and the Phone will work with products from its competition, such as the Apple Homekit. Essential, the new smartphone company founded by Android operating system creator Andy Rubin, "How do you build technology that consumers are is planning to ship its first pre-ordered flagship willing to invest in?" asked Rubin. "Inter-operability smartphones soon. The general launch date for is really, really important. We acknowledge that, the Essential Phone remains unknown, despite and we inter-operate with companies even if they months of publicity and continued intrigue among are our competitors." Silicon Valley's gadget-loving circles. Recently, Essential's exclusive carrier Sprint announced it While the 5.7-inch phone feels denser than its will open Phone pre-orders on its own website and Apple and Samsung counterparts, it is bereft of stores. Essential opened up pre-orders on its bloatware - rarely used default apps that are website in May when the product was first common in new smartphones. -

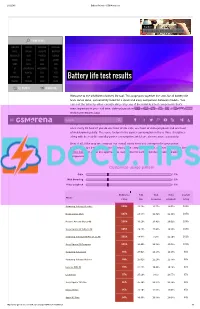

Battery Life Test Results HUAWEI TOSHIBA INTEX PLUM

2/12/2015 Battery life tests GSMArena.com Starborn SAMSUNG GALAXY S6 EDGE+ REVIEW PHONE FINDER SAMSUNG LENOVO VODAFONE VERYKOOL APPLE XIAOMI GIGABYTE MAXWEST MICROSOFT ACER PANTECH CELKON NOKIA ASUS XOLO GIONEE SONY OPPO LAVA VIVO LG BLACKBERRY MICROMAX NIU HTC ALCATEL BLU YEZZ MOTOROLA ZTE SPICE PARLA Battery life test results HUAWEI TOSHIBA INTEX PLUM ALL BRANDS RUMOR MILL Welcome to the GSMArena battery life tool. This page puts together the stats for all battery life tests we've done, conveniently listed for a quick and easy comparison between models. You can sort the table by either overall rating or by any of the individual test components that's most important to you call time, video playback or web browsing.TIP US 828K 100K You can find all about our84K 137K RSS LOG IN SIGN UP testing procedures here. SearchOur overall rating gives you an idea of how much battery backup you can get on a single charge. An overall rating of 40h means that you'll need to fully charge the device in question once every 40 hours if you do one hour of 3G calls, one hour of video playback and one hour of web browsing daily. The score factors in the power consumption in these three disciplines along with the reallife standby power consumption, which we also measure separately. Best of all, if the way we compute our overall rating does not correspond to your usage pattern, you are free to adjust the different usage components to get a closer match. Use the sliders below to adjust the approximate usage time for each of the three battery draining components. -

Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017

Week Ending: Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Inside This Issue: August 16, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple is finally getting serious about original TV programming. Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Two Apple executives have been meeting with Hollywood agents and producers to hear pitches about possible shows for Apple to buy, according to two producers who have met with them. Facebook Is Building A New $750 Million Data Center In Ohio The execs, Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg, were hired from Sony Pictures Television in June to oversee Apple's video programming. Products & Services New Apple, Samsung These pitch meetings have placed Apple in direct competition with Netflix, HBO and other Smartphone Challenger Is Finally distributors. Available For Pre-Order Some producers are eager to work with Apple, sensing a first-mover advantage. Others have a lot of YouTube TV Now Available To questions about how Apple will distribute its shows. When "House of Cards" debuted on Netflix, 50% Of U.S. Households marking the streaming service's entrance into original programming, the service already had a large catalog of licensed programming. Apple, Aetna Hold Secret Meetings To Bring Apple Watch To Millions Of Aetna Customers Apple doesn't have that -- but it does have iPhones in hundreds of millions of hands. Emerging Technology The meetings were first reported by The Wall Street Journal on Wednesday. Apple is said to be AI Is Taking Over The Cloud budgeting about $1 billion to acquire and produce original TV shows over the next year, according to the Journal. -

Should Google Be Taken at Its Word?

CAN GOOGLE BE TRUSTED? SHOULD GOOGLE BE TAKEN AT ITS WORD? IF SO, WHICH ONE? GOOGLE RECENTLY POSTED ABOUT “THE PRINCIPLES THAT HAVE GUIDED US FROM THE BEGINNING.” THE FIVE PRINCIPLES ARE: DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER. PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE. LABEL ADVERTISEMENTS CLEARLY. BE TRANSPARENT. LOYALTY, NOT LOCK-IN. BUT, CAN GOOGLE BE TAKEN AT ITS WORD? AND IF SO, WHICH ONE? HERE’S A LOOK AT WHAT GOOGLE EXECUTIVES HAVE SAID ABOUT THESE PRINCIPLES IN THE PAST. DECIDE FOR YOURSELF WHO TO TRUST. “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “I actually think most people don't want Google to answer their questions. They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.” Eric Schmidt The Wall Street Journal 8/14/10 EXEC. CHAIRMAN ERIC SCHMIDT “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.” Larry Page & Sergey Brin Stanford Thesis 1998 FOUNDERS BRIN & PAGE “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “The Google policy on a lot of things is to get right up to the creepy line.” Eric Schmidt at the Washington Ideas Forum 10/1/10 EXEC. CHAIRMAN ERIC SCHMIDT “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “We don’t monetize the thing we create…We monetize the people that use it. The more people use our products,0 the more opportunity we have to advertise to them.” Andy Rubin In the Plex SVP OF MOBILE ANDY RUBIN “PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE” “PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY -

Defendant Apple Inc.'S Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions Of

Case 4:20-cv-05640-YGR Document 410 Filed 04/08/21 Page 1 of 325 1 THEODORE J. BOUTROUS JR., SBN 132099 MARK A. PERRY, SBN 212532 [email protected] [email protected] 2 RICHARD J. DOREN, SBN 124666 CYNTHIA E. RICHMAN (D.C. Bar No. [email protected] 492089; pro hac vice) 3 DANIEL G. SWANSON, SBN 116556 [email protected] [email protected] GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP 4 JAY P. SRINIVASAN, SBN 181471 1050 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. [email protected] Washington, DC 20036 5 GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP Telephone: 202.955.8500 333 South Grand Avenue Facsimile: 202.467.0539 6 Los Angeles, CA 90071 Telephone: 213.229.7000 ETHAN DETTMER, SBN 196046 7 Facsimile: 213.229.7520 [email protected] ELI M. LAZARUS, SBN 284082 8 VERONICA S. MOYÉ (Texas Bar No. [email protected] 24000092; pro hac vice) GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP 9 [email protected] 555 Mission Street GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP San Francisco, CA 94105 10 2100 McKinney Avenue, Suite 1100 Telephone: 415.393.8200 Dallas, TX 75201 Facsimile: 415.393.8306 11 Telephone: 214.698.3100 Facsimile: 214.571.2900 Attorneys for Defendant APPLE INC. 12 13 14 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 OAKLAND DIVISION 18 19 EPIC GAMES, INC., Case No. 4:20-cv-05640-YGR 20 Plaintiff, Counter- DEFENDANT APPLE INC.’S PROPOSED defendant FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS 21 OF LAW v. 22 APPLE INC., The Honorable Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers 23 Defendant, 24 Counterclaimant. Trial: May 3, 2021 25 26 27 28 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP DEFENDANT APPLE INC.’S PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW, 4:20-cv-05640- YGR Case 4:20-cv-05640-YGR Document 410 Filed 04/08/21 Page 2 of 325 1 Apple Inc. -

Paper #5: Google Mobile

Yale University Thurmantap Arnold Project Digital Platform Theories of Harm Paper Series: 5 Google’s Anticompetitive Practices in Mobile: Creating Monopolies to Sustain a Monopoly May 2020 David Bassali Adam Kinkley Katie Ning Jackson Skeen Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. The Vicious Circle: Google’s Creation and Maintenance of its Android Monopoly 5 A. The Relationship Between Android and Google Search 7 B. Contractual Restrictions to Android Usage 8 1. Anti-Fragmentation Agreements 8 2. Mobile Application Distribution Agreements 9 C. Google’s AFAs and MADAs Stifle Competition by Foreclosing Rivals 12 1. Tying Google Apps to GMS Android 14 2. Tying GMS Android and Google Apps to Google Search 18 3. Tying GMS Apps Together 20 III. Google Further Entrenches its Mobile Search Monopoly Through Exclusive Dealing22 A. Google’s Exclusive Dealing is Anticompetitive 25 IV. Google’s Acquisition of Waze Further Forecloses Competition 26 A. Google’s Acquisition of Waze is Anticompetitive 29 V. Google’s Anticompetitive Actions Harm Consumers 31 VI. Google’s Counterarguments are Inadequate 37 A. Google Android 37 B. Google’s Exclusive Contracts 39 C. Google’s Acquisition of Waze 40 VII. Legal Analysis 41 A. Google Android 41 1. Possession of Monopoly Power in a Relevant Market 42 2. Willful Acquisition or Maintenance of Monopoly Power 43 a) Tying 44 b) Bundling 46 B. Google’s Exclusive Dealing 46 1. Market Definition 47 2. Foreclosure of Competition 48 3. Duration and Terminability of the Agreement 49 4. Evidence of Anticompetitive Intent 50 5. Offsetting Procompetitive Justifications 51 C. Google’s Acquisition of Waze 52 1.