Representing Cultural Difference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipi Instructions

Tipi Instructions Hello and thanks for buying one of our Tipi Tents. Here are the instructions for the best way to put it up, take it down and how to store when not in use. We’ve provided a step-by-step picture guide for you to follow along with the written instructions. At the bottom of these instructions we’ve added some advice and tips on how to get years of good service out of your tent by looking after it properly. Enjoy! And don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions, good ideas or better ways of doing it. Once you’ve erected your tent, we would love to see your Boutique Camping pictures, so please send them to us at [email protected]. They may even feature on our blog or Facebook page! Putting up a Tipi Tent Some general advice • We advise having 2 people to erect the tent, as it will of course simplify the process. By all means, you can put it up on your own, but of course the more the merrier, easier and quicker! • Find a flat piece of land, with ample space to comfortably put up your tent remembering to include room for the guy ropes • To prevent damaging the groundsheet, remove all sharp objects from the area. Things like stones and roots etc • Be careful when creating tension with the guy ropes, always try to keep the tension even, and never over do it. Be firm but gentle. • Before you peg out the tent, make sure all zips are closed, and check again when you adjust the guy ropes • Peg out the guy ropes in line with the tent seams How to Put Up Your Tipi A1)Open all bags and lay out all parts. -

The Sámi People and Their Culture the Sámi Or Saami Were Also Called Lapps Or Laplanders by the English

The Sámi people and their culture The Sámi or Saami were also called Lapps or Laplanders by the English. Sámi people consider the English terms derogatory. The Sámi are recognized as the only indigenous people of Europe. They have lived in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Their origins are Finno‐Ugric, a Hungarian and Yugra (Urals) past, inhabiting the Sápmi region. Today, the region encompasses large parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Murmansk Oblast (Kola Peninsula) of Russia. The Sámi people have their own language, culture and customs that differ from others around them. This has caused the Sámi social problems and culture clashes. As we learned from our Sámi culture presentation and a quote from ‐religiousstudiesproject.com the following: “The history between the Sámi and the Norwegian government has left a stain on the Sámi for generations: The Norwegianization policy undertaken by the Norwegian government from the 1850s up until the Second World War resulted in the apparent loss of Sami language and assimilation of the coastal Sami as an ethnically‐distinct people into the northern Norwegian population. Together with the rise of an ethno‐political movement since the 1970s, however, Sami culture has seen a revitalization of language, cultural activities, and ethnic identity (Brattland 2010:31).” Note: Suggested readings, ‐laits.utexas.edu, a 19‐part series by the University of Texas entitled “Sámi Culture.” The other reading is‐ unsr.vtaulicorpuz.org. It is a report by the United Nations on the rights of indigenous people such as the Sámi. Reindeer are the Sámi key element to how they live. -

Sámi Histories, Colonialism, and Finland

Sámi Histories, Colonialism, and Finland Veli-Pekka Lehtola Abstract. Public apologies, compensations, and repatriation policies have been forms of rec- onciliation processes by authorities in Nordic countries to recognize and take responsibility of possible injustices in Sámi histories. Support for reconciliation politics has not been unanimous, however. Some Finnish historians have been ready to reject totally the subjugation or colonial- ism towards the Sámi in the history of Finnish Lapland. The article analyzes the contexts for the reasoning and studies the special nature of Sámi- Finnish relations. More profound interpre- tations are encouraged to be done, examining colonial processes and structures to clarify what kind of social, linguistic, and cultural effects the asymmetrical power relations have had. Introduction careful historical study was carried out to investi- gate the history of injustice (Minde 2003), which “Colonialism may be dead, yet it is everywhere to was followed by the apology by the state for “those be seen.” gross injustices” that the minorities of the country (Dirks 2010:93) had suffered. The state extended its apology to vagrants and Kvens, too. The Norwegian state has There has been a lot of discussion in recent de- 1 also granted compensations, which older Sámi cades about the colonialist past of Nordic states. could apply for forfeited schooling. Already in There will never be a consensus, but some notable the first years, Kvens and Sámi sent thousands representatives of the dominant populations have of applications, which were largely approved shown willingness to reach some kind of recon- (Anttonen 2010:54–71). In all Nordic countries, ciliation with the past and build better relations the reconciliation theme has been evident when that way. -

Tent Inspection

Tent Guide Information referenced from the 2015 Frederick County Fire Prevention Code A Tent is defined as a structure, enclosure or shelter, with or without sidewalls or drops, constructed of fabric or pliable material supported by any manner except by air or the contents that it protects. All Tents: • A permit issued by the Frederick County Fire Marshal’s office shall be required for tents over 900 square feet not being used for recreational camping purposes. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 107.2 Permit Required.) • A detailed site and floor plan for tents with occupant load of 50 or more shall be required with each application for approval. The tent floor plan shall indicate details of means of egress, seating capacity, arrangement of seating and location and types of heating and electrical equipment. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.6 Construction documents.) • An unobstructed fire break passageway or fire road not less than 12 feet wide and free from guy ropes or other obstructions shall be maintained on all sides of all tents unless otherwise approved by the fire code official. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.8.6 Fire break.) • A certificate from an approved laboratory stating that the materials used in tent meet the flame- retardant criteria needed to pass NFPA Test Method 1 or Test Method 2. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.2 Flame propagation performance treatment.) • Approved “No Smoking” signs shall be conspicuously posted. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.6 Smoking.) • At least one 5lb. multipurpose 2A 10BC portable fire extinguisher shall be hung and tagged within 75 ft of travel distance. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

Pasvik–Inari Nature and History Shared Area Description

PASVIK–INARI NATURE AND HISTORY SHARED AREA DESCRIPTION The Pasvik River flows from the largest lake in Finn- is recommended only for very experienced hikers, ish Lapland, Lake Inari, and extends to the Barents some paths are marked for shorter visits. Lake Inari Sea on the border of Norway and Russia. The valley and its tributaries are ideal for boating or paddling, forms a diverse habitat for a wide variety of plants and in winter the area can be explored on skis or a and animals. The Pasvik River is especially known for dog sled. The border mark at Muotkavaara, where its rich bird life. the borders of Finland, Norway and Russia meet, can The rugged wilderness that surrounds the river be reached by foot or on skis. valley astonishes with its serene beauty. A vast Several protected areas in the three neighbouring pine forest area dotted with small bogs, ponds and countries have been established to preserve these streams stretches from Vätsäri in Finland to Pasvik in great wilderness areas. A vast trilateral co-operation Norway and Russia. area stretching across three national borders, con- The captivating wilderness offers an excellent sisting of the Vätsäri Wilderness Area in Finland, the setting for hiking and recreation. From mid-May Øvre Pasvik National Park, Øvre Pasvik Landscape until the end of July the midnight sun lights up the Protection Area and Pasvik Nature Reserve in Nor- forest. The numerous streams and lakes provide way, and Pasvik Zapovednik in Russia, is protected. ample catch for anglers who wish to enjoy the calm backwoods. -

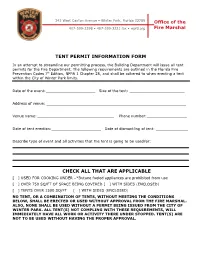

Tent & Events Under a Tent Permit Application

343 West Canton Avenue • Winter Park, Florida 32789 Office of the 407-599-3298 • 407-599-3231 fax • wpfd.org Fire Marshal TENT PERMIT INFORMATION FORM In an attempt to streamline our permitting process, the Building Department will issue all tent permits for the Fire Department. The following requirements are outlined in the Florida Fire Prevention Codes 7th Edition, NFPA 1 Chapter 25, and shall be adhered to when erecting a tent within the City of Winter Park limits. Date of the event: Size of the tent: Address of venue: Venue name: Phone number: _ Date of tent erection: Date of dismantling of tent: Describe type of event and all activities that the tent is going to be used for: CHECK ALL THAT ARE APPLICABLE [ ] USED FOR COOKING UNDER –*Butane fueled appliances are prohibited from use [ ] OVER 750 SQ/FT OF SPACE BEING COVERED [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) [ ] TENTS OVER 1500 SQ/FT [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) NO TENT, OR A COMBINATION OF TENTS, WITHOUT MEETING THE CONDITIONS BELOW, SHALL BE ERECTED OR USED WITHOUT APPROVAL FROM THE FIRE MARSHAL. ALSO, NONE SHALL BE USED WITHOUT A PERMIT BEING ISSUED FROM THE CITY OF WINTER PARK. ALL TENT(S) NOT COMPLING WITH THESE REQUIREMENTS, WILL IMMEDIATELY HAVE ALL WORK OR ACTIVITY THERE UNDER STOPPED. TENT(S) ARE NOT TO BE USED WITHOUT HAVING THE PROPER APPROVAL. TENTS USED FOR COOKING 1. Permits for all tents used to cook under, shall be submitted no later than five business days prior to the erection of the tents. An inspection at least 90 minutes prior to the cooking operations and subject to all fees per the City of Winter Park may be required. -

Cinema Across Borders : National Differences in Sámi Filmmaking In

CINEMA ACROSS BORDERS : NATIONAL DIFFERENCES IN SÁMI FILMMAKING IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES by Rachael Crawley Bachelor of Arts, Cinema Studies/Russian Language and Literature University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario 2013 A thesis presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Film + Photography Preservation and Collections Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Rachael Crawley, 2017 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Cinema Across Borders: National Differences in Sámi Filmmaking in the Nordic Countries Master of Arts, 2017 Rachael Crawley Film + Photography Preservation and Collections Management Ryerson University The cinema of the Sámi people, of northern Fennoscandia and Russia (Sápmi), has flourished since the turn of the millennium. This thesis summarizes the history of Sámi film, its current infrastructure, and the differences in filmmaking trends between the three Nordic countries of Sápmi. It also includes a list of all known Sámi productions and organizations funding Sámi film. By exploring the differences in funding in the Nordic countries, it examines the relative lack of Sámi film production and infrastructure in Sweden, as compared to Norway and Finland. -

Two Hearth- Row Sites in Pasvik, Arctic Norway

Brodtkorbneset and Steintjørna: Two Hearth- Row Sites in Pasvik, Arctic Norway Bjørnar J. Olsen Bjørnar J. Olsen, Department of Archaeology, History, Religious Studies and Theology, University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway, P.O. box 6050 Langnes, 9037 Tromsø: [email protected] Abstract During the Viking Age and the early medieval period, hearth-row sites became a distinct feature of Sámi settlements over the vast interior region of Northern Fennoscandia. Consist- ing of large, rectangular hearths organized in a linear pattern, these sites represent a new way of organizing domestic space and also reflect new environmental preferences. In this paper, the author gives an overview of the investigations conducted at two hearth-row sites, Steintjørna and Brodtkorbneset, in Pasvik, Arctic Norway. Based on the excavated material, the author discusses changes in settlement pattern, reindeer economies, and the organiza- tion of domestic space. He also discusses the role that the hearths themselves may have played in negotiating internal social dynamics and in inter-ethnic contacts of the Late Viking Age and the early medieval period. 1 Introduction in the south-western part of the Kola Penin- sula (Muraskin & Kolpakov, this volume). The Viking Age and early medieval period More intriguing, however, is the discovered (c. 800 – 1300 AD) brought some remark- hearth-row site at Aursjøen, Lesja, in Opp- able changes to the indigenous Sámi socie- land County, which suggests that their distri- ties in Northern Fennoscandia, including bution even included the mountain areas of changes in settlement pattern, organization interior Southern Norway, more than 1,200 of domestic space, ritual manifestations, km south-west of the north-easternmost exchange networks, economy, and animal known sites (Bergstøl 2008: 141-142; Reitan relationships. -

Action Plan Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park 2019-2028

Action plan Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park 2019-2028 2019 Action plan Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park 2019-2028 Date: 31.1.2019 Authors: Kalske, T., Tervo, R., Kollstrøm, R., Polikarpova, N. and Trusova, M. Cover photo: Young generation of birders and environmentalists looking into the future (Pasvik Zapovednik, О. Кrotova) The Trilateral Advisory Board: FIN Metsähallitus, Parks & Wildlife Finland Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environments in Lapland (Lapland ELY-centre) Inari Municipality NOR Office of the Finnmark County Governor Øvre Pasvik National Park Board Sør-Varanger Municipality RUS Pasvik Zapovednik Pechenga District Municipality Nikel Local Municipality Ministry of Natural Resource and Ecology of the Murmansk region Ministry of Economic Development of the Murmansk region, Tourism division Observers: WWF Barents Office Russia, NIBIO Svanhovd Norway Contacts: FINLAND NORWAY Metsähallitus, Parks & Wildlife Finland Troms and Finnmark County Governor Ivalo Customer Service Tel. +47 789 50 300 Tel. +358 205 64 7701 [email protected] [email protected] Northern Lapland Nature Centre Siida RUSSIA Tel. +358 205 64 7740 Pasvik State Nature Reserve [email protected] (Pasvik Zapovednik) Tel./fax: +7 815 54 5 07 00 [email protected] (Nikel) [email protected] (Rajakoski) 2 Action Plan Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park 2019-2028 3 Preface In this 10-year Action Plan for the Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park, we present the background of the long-lasting nature protection and management cooperation, our mutual vision and mission, as well as the concrete development ideas of the cooperation for the next decade. The plan is considered as an advisory plan focusing on common long-term guidance and cooperation. -

Perinteinen Ja Paikallinen Tieto Maankäytön Suunnittelussa

Perinteinen ja paikallinen tieto maankäytön suunnittelussa - esimerkkinä Enontekiö Traditional and Local Knowledge in Land Use Planning: - The Enontekiö Municipality in the Finnish Saami homeland as an example Inkeri Markkula, Minna Turunen, Seija Tuulentie, Ari Nikula English abstract The Finnish Land Use and Building Act aims to ensure local people’s rights to participate in land use planning. Integration of traditional and local knowledge into planning processes enhances participation. The Convention on Biological Diversity requires its parties to respect, preserve and maintain indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge. In the Saami Homeland in Finland, this objective is pursued by applying the Akwé: Kon Voluntary Guidelines. This study addresses the application of the Guidelines, inclusion of traditional and local knowledge in land use planning, and use of participatory geographic information systems (PPGIS) in the Enontekiö municipality. The study is based on a PPGIS survey and interviews with local Saami herders and land use planning officials conducted in Enontekiö in 2016-2018. Challenges remain regarding inclusion of traditional and local knowledge in land use planning. The Saami informants reported that the herding legislation fails to protect their traditional practices and knowledge. The planning officials acknowledged a need to make such knowledge more spatially explicit and to find ways of incorporating narrative knowledge into the planning systems. PPGIS is a suitable tool to document traditional and local knowledge. However, questions remain regarding access to natural resources and the Saami heritage. Keywords: Akwé:Kon -guidelines, land use planning, traditional and local knowledge, Saami Homeland 1 Tiivistelmä Maankäyttö- ja rakennuslaki edellyttää vuorovaikutteisuutta ja paikallisten ihmisten osallistamista maankäytön suunnittelussa. -

Nordic Tipis – a Home for Big and Small Adventures ROOTS

ADVENTURE Nordic tipis – a home for big and small adventures ROOTS THE PEOPLE OF THE SUN AND WIND The Sami are the only indigenous people in Europe. They used to live as nomadic trackers, hunters and reindeer keepers. Their country Sápmi extends over northern Scandinavia and parts of Russia. The tough climate, the long winter and nature’s tribulations were part of these people’s everyday life. The lifecycle of the reindeer was also theirs and they accompanied their animals to their summer and winter grazing grounds. Traditionally, the Sami lived in a “kåta” in the winter. The focal point of the tent was the fire which gave them heat and light and a feel of homeliness. Our company was started in Moskosel, a little village in Swedish Lapland, where the Sami heritage is ever present. Our hope is that, when you choose a Tentipi Nordic tipi, you will feel the same closeness to the elements as the indigenous people do. Separating the reindeer – an activity steeped in cultural heritage that is still a central part of reindeer husbandry © Peter Rosén CONTENT 04 Adventure tent range 24 Stove and fire equipment 26 Tent accessories 31 Sustainability 32 Handicraft and material 34 Crucial features 36 Event tents 38 Tentipi Camp 39 Further reading Wanted: a home in nature The idea came to me when I was sitting by a stream, far out in the wilds of Lapland. Tired and sweaty after a long day of exciting canoeing, what I really wanted to do was socialise with my friends while eating dinner and chatting around a fire.