Marginalized Meanings of Democracy in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and Its Importance for Modem Democracy

DEMOCRAC AHMOKPATI The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and its Importance for Modern Democracy Mogens Herman Hansen The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and its Importance for Modem Democracy B y M ogens H erman H ansen Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser 93 Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Copenhagen 2005 Abstract The two studies printed here investigate to what extent there is a con nection between ancient and modem democracy. The first study treats the tradition of ancient Greek democracy, especially the tradition of Athenian democracy from ca. 1750 to the present day. It is argued that in ideology there is a remarkable resemblance between the Athenian democracy in the Classical period and the modem liberal democracy in the 19th and 20th centuries. On the other hand no direct tradition con nects modem liberal democracy with its ancient ancestor. Not one single Athenian institution has been copied by a modem democracy, and it is only from ca. 1850 onwards that the ideals cherished by the Athenian democrats were referred to approvingly by modem cham pions of democracy. It is in fact the IT technology and its potential for a return to a more direct form of democracy which has given rise to a hitherto unmatched interest in the Athenian democratic institutions. This is the topic of the second study in which it is argued that the focus of the contemporary interest is on the Athenian system of sortition and rotation rather than on the popular assembly. Contents The Tradition of Democracy from Antiquity to the Present Time ................................................................. -

PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 A.M

Carleton University Fall 2019 Department of Political Science Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 a.m. – 2:25 p.m. Please confirm location on Carleton Central Instructor: Professor Achim Hurrelmann Office: D687 Loeb Building Office Hours: Mondays, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and by appointment Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2294 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @achimhurrelmann Course description: Over the past seventy years, European integration has made significant contributions to peace, economic prosperity and cultural exchange in Europe. By contrast, the effects of integration on the democratic quality of government have been more ambiguous. The European Union (EU) possesses more mechanisms of democratic input than any other international organization, most importantly the directly elected European Parliament (EP). At the same time, the EU’s political processes are often described as insufficiently democratic, and European integration is said to have undermined the quality of national democracy in the member states. Concerns about a “democratic deficit” of the EU have not only been an important topic of scholarly debate about European integration, but have also constituted a major argument of populist and Euroskeptic political mobilization, for instance in the “Brexit” referendum. This course approaches democracy in the EU from three angles. First, it reviews the EU’s democratic institutions and associated practices of citizen participation: How -

Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond 2 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 July 1997 Prof. Dr. Larry Diamond Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 USA e-mail: [email protected] and International Forum for Democratic Studies National Endowment for Democracy 1101 15th Street, NW, Suite 802 Washington, DC 20005 USA T 001/202/293-0300 F 001/202/293-0258 Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. It includes papers by the Department’s teaching and research staff, visiting professors, students, visiting fellows, and invited participants in seminars, workshops, and conferences. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions. All rights are reserved. Abstract The “Third Wave” of global democratization, which began in 1974, now appears to be drawing to a close. While the number of “electoral democracies” has tripled since 1974, the rate of increase has slowed every year since 1991 (when the number jumped by almost 20 percent) and is now near zero. -

Democracy on the Precipice Council of Europe Democracy 2011-12 Council of Europe Publishing Debates

Democracy on the Precipice Democracy Democracy is well-established and soundly practiced in most European countries. But despite unprecedented progress, there is growing dissatisfaction with the state of democracy and deepening mistrust of democratic institutions; a situation exacer- Democracy on the Precipice bated by the economic crisis. Are Europe’s democracies really under threat? Has the traditional model of European democracy exhausted its potential? A broad consensus is forming as to the urgent need to examine the origins of the crisis and to explore Council of Europe visions and strategies which could contribute to rebuilding confidence in democracy. Democracy Debates 2011-12 As Europe’s guardian of democracy, human rights and the rule of law, the Council of Europe is committed to exploring the state and practice of European democracy, as Debates of Europe Publishing 2011-12 Council Council of Europe Democracy well as identifying new challenges and anticipating future trends. In order to facilitate Preface by Thorbjørn Jagland this reflection, the Council of Europe held a series of Democracy Debates with the participation of renowned specialists working in a variety of backgrounds and disciplines. This publication presents the eight Democracy Debate lectures. Each presentation Zygmunt Bauman analyses a specific aspect of democracy today, placing the issues not only in their political context but also addressing the historical, technological and communication Ulrich Beck dimensions. The authors make proposals on ways to improve democratic governance Ayşe Kadıoğlu and offer their predictions on how democracy in Europe may evolve. Together, the presentations contribute to improving our understanding of democracy today and to John Keane recognising the ways it could be protected and strengthened. -

Types of Democracy the Democratic Form of Government Is An

Types of Democracy The democratic form of government is an institutional configuration that allows for popular participation through the electoral process. According to political scientist Robert Dahl, the democratic ideal is based on two principles: political participation and political contestation. Political participation requires that all the people who are eligible to vote can vote. Elections must be free, fair, and competitive. Once the votes have been cast and the winner announced, power must be peacefully transferred from one individual to another. These criteria are to be replicated on a local, state, and national level. A more robust conceptualization of democracy emphasizes what Dahl refers to as political contestation. Contestation refers to the ability of people to express their discontent through freedom of the speech and press. People should have the ability to meet and discuss their views on political issues without fear of persecution from the state. Democratic regimes that guarantee both electoral freedoms and civil rights are referred to as liberal democracies. In the subfield of Comparative Politics, there is a rich body of literature dealing specifically with the intricacies of the democratic form of government. These scholarly works draw distinctions between democratic regimes based on representative government, the institutional balance of power, and the electoral procedure. There are many shades of democracy, each of which has its own benefits and disadvantages. Types of Democracy The broadest differentiation that scholars make between democracies is based on the nature of representative government. There are two categories: direct democracy and representative democracy. We can identify examples of both in the world today. -

Social Studies Grade 7 Week of 4-6-20 1. Log Onto Clever with Your

Social Studies Grade 7 Week of 4-6-20 1. Log onto Clever with your BPS username and password. 2. Log into Newsela 3. Copy and paste this link into your browser: https://newsela.com/subject/other/2000220316 4. Complete the readings and assignments listed. If you can’t access the articles through Newsela, they are saved as PDFs under the Grade 7 Social Studies folder on the BPSMA Learning Resources Site. They are: • Democracy: A New Idea in Ancient Greece • Ancient Greece: Democracy is Born • Green Influence on U.S. Demoracy Complete the following: Directions: Read the three articles in the text set. Remember, you can change the reading level to what is most comfortable for you. While reading, use the following protocols: Handling changes in your life is an important skill to gain, especially during these times. Use the following supports to help get the most out of these texts. Highlight in PINK any words in the text you do not understand. Highlight in BLUE anything that you have a question about. Write an annotation to ask your question. (You can highlight right in the article. Click on the word or text with your mouse. Once you let go of the mouse, the highlight/annotation box will appear on your right. You can choose the color of the highlight and write a note or question in the annotation box). Pre-Reading Activity: KWL: Complete the KWL Chart to keep your information organized. You may use the one below or create your own on a piece of paper. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OUDVcJA6hjcteIhpA0f5ssvk28WNBhlK/view Post-Reading Activity: After reading the articles, complete a Venn diagram to compare and contrast the democracy of Ancient Greece and the United States. -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017

St Comp Int Dev https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017 Jan Teorell1 & Michael Coppedge2 & Staffan Lindberg3 & Svend-Erik Skaaning 4 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This paper presents a new measure polyarchy for a global sample of 182 countries from 1900 to 2017 based on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data, deriving from an expert survey of more than 3000 country experts from around the world, with on average 5 experts rating each indicator. By measuring the five compo- nents of Elected Officials, Clean Elections, Associational Autonomy, Inclusive Citi- zenship, and Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information separately, we anchor this new index directly in Dahl’s(1971) extremely influential theoretical framework. The paper describes how the five polyarchy components were measured and provides the rationale for how to aggregate them to the polyarchy scale. We find Previous versions of this paper were presented at the APSA Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, August 28- 31, 2014, at the Carlos III-Juan March Institute of Social Sciences, Madrid, November 28, 2014, and at the European University Institute, Fiesole, January 20, 2016. Any remaining omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors. Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018- 9268-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. * Jan Teorell [email protected] Michael Coppedge [email protected] Staffan Lindberg [email protected] -

1 European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS

In Journal of Common Market Studies, March 2013, Vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 000-000. European Demoicracy and Its Crisis1 KALYPSO NICOLAÏDIS Abstract This article offers an overview and reconsideration of the idea of European demoicracy in the context of the current crisis. It defines demoicracy as ‘a Union of peoples, understood both as states and as citizens, who govern together but not as one,’ and argues that the concept is best understood as a third way, distinct from both national and supranational versions of single demos polities. The concept of demoicracy can serve both as an analytical lens for the EU-as-is and as a normative benchmark, but one which cannot simply be inferred from its praxis. Instead, the article deploys a ‘normative-inductive’ approach according to which the EU’s normative core - transnational non-domination and transnational mutual recognition - is grounded on what the EU still seeks to escape. Such norms need to be protected and perfected if the EU is to live up to its essence. The article suggests ten tentative guiding principles for the EU to continue turning such norms into practice. _____________________________________________________________________ The aftershock of the 2008 global financial crisis in the EU has come to be widely seen as a crisis of ‘democracy’ in Europe. This article starts from the premise that the EU’s legitimacy deficit will not be addressed by tinkering with its institutions. Instead, the name of the democratic game in Europe today is democratic interdependence: the Union magnifies the pathologies of the national democracies in its midst, even as it entrenches and nurtures these democracies, who in turn affect each other in profound ways. -

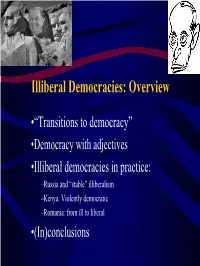

Illiberal Democracies: Overview

Illiberal Democracies: Overview •“Transitions to democracy” •Democracy with adjectives •Illiberal democracies in practice: –Russia and “stable” illiberalism –Kenya: Violently democratic –Romania: from ill to liberal •(In)conclusions “Transitions to democracy” • Transitions literature comes out of a reading of democratization in L.Am., ‘70s & ‘80s. • Mechanisms of transition (O’Donnell and Schmitter): – Splits appear in the authoritarian regime – Civil society and opposition develop – “Pacted” transitions Democracy with Adjectives • Problem: The transitions model is excessively teleological and just inaccurate • “Illiberal” meets “democracy” – What is democracy (again, and in brief)? – Why add “liberal”? – What in an illiberal democracy is “ill”? A Typology of Regimes Chart taken from Larry Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes” Journal of Democracy 13: 2 (2002) How do “gray zone” regimes develop? • Thomas Carothers: Absence of pre-conditions to democracy, which is tied to… (Culturalist) • Fareed Zakaria: When baking a liberal democracy, liberalize then democratize (Institutionalist). • Michael McFaul: Domestic balance of power at the outset matters (path dependence). Where even, illiberalism may develop (Rationalist). Russia Poland Case studies: Russia • 1991-93: An even balance of power between Yeltsin and reformers feeds into political ambiguity…and illiberalism • After Sept 1993 - Yeltsin takes the advantage and uses it to shape Russia into a delegative democracy • The creation of President Putin • Putin and the “dictatorship of law” -

DEMOPOLIS Democracy Before Liberalism in Theory and Practice

Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 DEMOPOLIS Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice JOSIAH OBER Stanford University, California v Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 Contents List of Figures page xi List of Tables xii Preface: Democracy before Liberalism xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on the Text xix 1 Basic Democracy 1 1.1 Political Theory 1 1.2 Why before Liberalism? 5 1.3 Normative Theory, Positive Theory, History 11 1.4 Sketch of the Argument 14 2 The Meaning of Democracy in Classical Athens 18 2.1 Athenian Political History 19 2.2 Original Greek Defnition 22 2.3 Mature Greek Defnition 29 3 Founding Demopolis 34 3.1 Founders and the Ends of the State 36 3.2 Authority and Citizenship 44 3.3 Participation 48 3.4 Legislation 50 3.5 Entrenchment 52 3.6 Exit, Entrance, Assent 54 3.7 Naming the Regime 57 4 Legitimacy and Civic Education 59 4.1 Material Goods and Democratic Goods 60 4.2 Limited-Access States 63 4.3 Hobbes’s Challenge 64 4.4 Civic Education 71 ix Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 x Contents 5 Human Capacities and Civic Participation 77 5.1 Sociability 79 5.2 Rationality 83 5.3 Communication 87 5.4 Exercise of Capacities as a Democratic Good 88 5.5 Free Exercise and Participatory Citizenship 93 5.6 From Capacities to Security and Prosperity 98 6 Civic Dignity -

MARIA VICTORIA MURILLO 420 118Th Street, 8Th Floor, IAD • Columbia University Phone (212) 854 4671 • Fax (212) 854 4607 • Email: [email protected]

MARIA VICTORIA MURILLO 420 118th Street, 8th floor, IAD • Columbia University Phone (212) 854 4671 • Fax (212) 854 4607 • Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University: PhD, November 1997; M.A., May 1994 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Licenciada en Ciencia Política, June 1991 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Columbia University, Professor, Department of Political Science/ School of International and Public Affairs, 2003- present (Associate Professor, 2003-2010, Director of Graduate Studies, 2010-14). Yale University, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, July 2002-December 2002 . Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, January 1998-July 2002. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Visiting Professor, 2009-present. AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS Midwest Political Science Association, Best Paper in International Relations presented in the MPSA 2015 conference (with Pablo Pinto). Comparative Political Studies; Editorial Board Best Paper Award, 2014 (with Ernesto Calvo). American Political Science Association, Luebbert Award for the Best Comparative Politics Article published in 2004-05 (with Ernesto Calvo). Russell Sage Visiting Fellowship, 2011-12. Fulbright Foundation, William Fulbright Foreign Scholar 2008-09. Harvard University, Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies Post-Doctoral Fellowship, 1996-1997. Harvard University, Peggy Rockefeller Research Fellowship, July 2002-December 2002. PUBLICATIONS IN ENGLISH Books: . The Politics of Institutional Weakness: Lessons from Latin America (with Daniel Brinks