Better Work Discussion Paper Series: No. 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Monthly Catalog ISSUED by the Superintendent of Documents

United States GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Monthly Catalog ISSUED BY THE Superintendent of Documents no . 608 SEPTEMBER I 945 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 194$ FOR SALE BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS, U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 25, D. C., PRICE 20 CENTS PER COPY SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $2.25 PER YEAR FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION $2.85 PER YEAR Contents Page Abbreviations, Explanation_________ iv Alphabetical List of Government Authors________________________ v General Information_______________ 927 Notes of General Interest__________ 930 New Classification Numbers, etc____ 931 Congressional Set_________________ 932 Monthly Catalog__________________ 933 m Abbreviations Amendment, amendments_____ amdt., amdts. Paragraph, paragraphs---------------- par., pars. Appendix---------------------------------------------- app. Part, parts------------------------------------- pt., pts. Article, articles________________________ art. Plate, plates____________________________ pi. Chapter, chapters_____________________ chap. Portrait, portraits_____________________ por. Congress-------------------------------------------- Cong. Quarto___________________________________40 Department__________________________Dept. Report_________________________________ rp. Document_____________________________ doc. Saint----------------------------------------------------- st. Facsimile, facsimiles_______________ facsim. Section, sections_______________________ sec. Folio____________________________________fo Senate, Senate bill______________________ -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

A7fgleefaklatit" "

HOT DANCE/ELECTRONIC SONGSTM DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUMST" LIST TITLECERTIFICATION Artist LAST I THIS ARTISTCERTIFICATION MEEK PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION IABEL WEEK WEER IMPRINT/DISTRIBUTING LABEL (HART NEW LA ROUX Trouble In Paradise j LATCHA Disclosure Featuring Sam Smith I 4S IE4OGISINCHLIqTIPILMIENDA M POSTOOR/CHERWIREE/INTERSCOPEAGA 0 DKUOSUKOILLITISCEGLARTENCESSINININNIEN 2 2 LINDSEY STIRLING Shatter Me 13 In SUMMERS Calvin Harris , 20 LINDSEYSTOmP 0 (MARRS KAMM TUN. DECONSTRUCTION/ELY MANTRA/ROC NAROMOLUMBIA DISCLOSURE Settle 60 TURN DOWN FOR WHAT DJ Snake &cLoiLlulop lO ME IHOO/PMR/04RRYIRE 17iNTF RSCOPF /oGA 3 3 3 A 33 DI SRAM .I.SMII H (1.14.94114.W.GRKAHOSE.M. BIUSSO) A1 LADY GAGA ARTPOP 37 RATHER BE STREAMLINE/IA.5(0PC/. Clean Bandit Featuring Jess Glynne 4 25 O 0 0 01111JRATIERSONA.CHATTO (LNANERAPMTERSON.N.MARSHALL) BIG BEAT/RRP DAFT PUNKARandom Access Memories 63 5 DAFT LIFE/COLUMBIA BREAK FREE AsLA,.......arih,Aoirtiaza Grande Featuring 4 4 O La Roux ZEDOMAx MARTIN (A2 0 0 C DEADMAUS while(1<2) 6 A SKY FULL OF STARS Coldplay TAAUSTRAP/ASTRALWERXSKAINTOL 6 4 0 0 WOURNIAPIPPNRUNTILIANIONNEARAPINNUIWIEWILILDAWIDUAIWRWIN,IN me.otoPt N.LL, Finds AVICII True 45 WASTED Tiesto Featuring Matthew Koma 0 PRMONSLAND 6 7 7 5 14 ILIEWIMILUIESTOMOR1STACINDIRWIVIUNESULAWKIKG4S1 NAM INIDNIVIINAAWERICASIPN, `Paradise' SYLVAN ESSO Sylvan Esso 11 8 PARTISAN HIDEAWAY Kiesza O R.SAFUNI IK.R.ELLESTAD.R.SAFUNI) LORAL LEGENDNITH . BROADWAWISUND/REPUBUC 8 14 La Roux follows its 0 0 12 KIESZA Hideaway (EP) 3 0 LONA LEGENDATHR BROADWAY/614ND Grammy -winning self -titled 8 9 DARE (LA LA LA) Shakira 5 18 Di LK.SoauSAR.CR4IGHIARAISNOUKIRLUANOLPRIPTEALLINAITIXXIIMNARINEGIRWICIDL Al NA debut with its first No.1 10 SKRILLEX Recess 19 BEAT/OWSLA/ATLANTKAG onDance/Electronic WAVES Mr. -

Contextual Predictability Norms for Pairs of Words Differing in a Single Letter

H I LLINI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ~66' Technical Report No. 260 CONTEXTUAL PREDICTABILITY NORMS FOR PAIRS OF WORDS DIFFERING IN A SINGLE LETTER Harry E. Blanchard, George W. McConkie and David Zola University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign August 1982 Center for the Study of Reading TECHNICAL REPORTS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 BOLT BERANEK AND NEWMAN INC. 50 Moulton Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02238 [LtHE LIBRARY OF TH-I The National Institute of Education U.S. Department of Education UNIVE.SITY OF ILL:S Washington. D.C. 20208 IT ^a -- CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF READING Technical Report No. 260 CONTEXTUAL PREDICTABILITY' NORMS FOR PAIRS OF WORDS DIFFERING IN A SINGLE LETTER Harry E. Blanchard, George W. McConkie and David Zola University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign August 1982 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc. 51 Gerty Drive 50 Moulton Street Champaign, Illinois 61820. Cambridge, Massachusetts 02238 This research was conducted under grants MH 32884 and MH 33408 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the first author, and National Institute of Education contract HEW-NIE-C-400-76-0116 to the Center for the Study of Reading. Copies of this report can be obtained by writing to George W. McConkie, Center for the Study of Reading, 51 Gerty Drive, Champaign, Illinois 61820. EDITORIAL BOARD William Nagy and Stephen Wilhite Co--Editors Harry Blanchard Anne Hay Charlotte Blomeyer Asghar Iran-Nejad Nancy Bryant Margi Laff Avon Crismore Terence Turner Meg Sallagher Paul Wilson Abstract Predictability Norms Four hundred sixty-seven pairs of short texts were written. -

Band Song-List

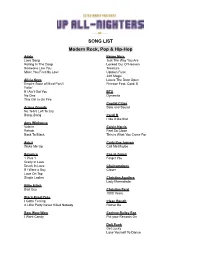

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Hold It High (Cadence) on the Road Again the U.S

Hold It High (cadence) On the Road Again The U.S. Air Force Willie Nelson Brave Never Gonna Give You Up Sara Bareilles Rick Astley My Hero Home Foo Fighters Phillip Phillips Fight Song We Are The Champions Rachel Platten Queen Can’t Stop the Feeling (from Trolls) When Can I See You Again? (from Wreck-It Ralph) Justin Timberlake Owl City Dog Days Are Over Rise Up Florence & The Machine Andra Day Don’t You Worry ‘Bout A Thing (from SING) Holding Out For A Hero (from Footloose) Tori Kelly Bonnie Tyler Heroes (We Could Be) Firework Alesso, Tove Lo Katy Perry Daisies You’ll Always Find Your Way Back Home Katy Perry Hannah Montana How Far I’ll Go (from Moana) You Got It (The Right Stuff) Auli’I Cravalho New Kids On The Block Friends Are Family (from LEGO Batman Movie) Wild Things Oh, Hush!, Jeff Lewis, Will Arnett Alessia Cara 355th Force Support Squadron Marketing // Davis-Monthan Air Force Base Castle On The Hill Shake It Off Ed Sheeran Taylor Swift How Far We’ve Come Something To Be Proud Of Matchbox Twenty Montogomery Gentry I Will Wait I’m Still Standing Mumford & Sons Elton John Keep Your Head Up Go The Distance (from Hercules) Andy Grammar Roger Bart Leaving, On A Jet Plane Scars To Your Beautiful John Denver Alessia Cara Miles Apart We Know The Way (from Moana) Yellowcard Opetaia Foa’I, Lin-Manuel Miranda Into The Unknown (from Frozen 2) Part Of Me Idina Menzel, AURORA Katy Perry Budapest Just Around The Riverbend (from Pocahontas) George Ezra Judy Kuhn Boomerang I Will Survive JoJo Siwa Gloria Gaynor This Is Me (from The Greatest Showman) Tightrope (feat. -

Top 40 Hits of 2014 Show Date: Weekend of December 27-28, 2014 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg

Show Code: #14-52 Top 40 Hits of 2014 Show Date: Weekend of December 27-28, 2014 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Content: #40 “HABITS (STAY HIGH)” – Tove Lo #39 “HOLD ON, WE’RE GOING HOME” – Drake f/Majid Jordan #38 “LET HER GO” – Passenger Commercials: :30 Subway :30 CustomInk.com :60 Sprint/Half Price Outcue: “...Restrictions apply.” Segment Time: 13:56 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Billboard: Geico Content: #37 “ROYALS” – Lorde #36 “ME AND MY BROKEN HEART” – Rixton Extra: “UNCONDITIONALLY” – Katy Perry #35 “NEON LIGHTS” – Demi Lovato #34 “RATHER BE” – Clean Bandit f/Jess Glynne Commercials: :30 Relativity/Woman :60 Proactiv :30 Zynga/WordsWith Outcue: “...best friend win.” Segment Time: 20:33 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Billboard: Subway Content: #33 “STAY THE NIGHT” – Zedd f/Hayley Williams #32 “BREAK FREE” – Ariana Grande f/Zedd #31 “BANG BANG” – Jessie J, Ariana Grande & Nicki Minaj Extra: “BLANK SPACE” – Taylor Swift Commercials: :30 Experian :30 VistaPrint Outcue: “...promo code 4141.” Segment Time: 16:54 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “LOVE NEVER FELT SO GOOD” – Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Outcue: “… Michael and JT.” (sfx) Segment Time: 4:08 Hour 1 Total Time: 60:31 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #14-52 Show Date: Weekend of December 27-28, 2014 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard None Seg. 1 Content: #30 “TURN DOWN FOR WHAT” – DJ Snake & Lil Jon #29 “CLASSIC” – MKTO #28 “MAPS” – Maroon 5 Commercials: :30 Zynga/WordsWith :30 MCSR/Renew :60 Sprint/Half Price Outcue: “...Restrictions apply.” Segment Time: 11:31 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

The Influence of Network Design on Firm Performance – Perspectives and Empirical Evidence

THE INFLUENCE OF NETWORK DESIGN ON FIRM PERFORMANCE – PERSPECTIVES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften durch die Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster WESTFÄLISCHE WILHELMS-UNIVERSITÄT MÜNSTER vorgelegt von BRINJA MEISEBERG aus Bottrop Münster, 2010 Erster Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Thomas Ehrmann Zweite Berichterstatterin: Prof. Dr. Anja Tuschke Dekan: Prof. Dr. Stefan Klein Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 12. April 2010 Acknowledgements The process of writing this dissertation was accompanied by a number of people to whom I would like to express my gratitude for their support. I am sincerely indebted to my dissertation advisor, Prof. Dr. Thomas Ehrmann, Institute of Stra- tegic Management at Münster University, for his guidance and promotion of my research efforts, and for providing extensive expertise and creative commentary whenever needed. I am also in- debted for his continuous trust in taking me on as a research assistant. I thank Prof. Dr. Anja Tuschke, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, for her co-supervisory of my dissertation. I extend my thanks to Prof. Dr. Martin Bohl and Prof. Dr. Gerhard Schewe, both of Münster University, for accepting the responsibility to join the dissertation committee. Finally, I thank Dr. Hendrik Schmale, Sandra Stevermüer and Alfred Koch for being great friends and colleagues. I am deeply grateful to Dagmar and Rolf Meiseberg for promoting and challenging critical thinking in any endeavours, and for being a constant source of love, concern, support and strength, all these years. I thank Prof. Dr. Frank Ückert for supporting me every step of the way. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................. -

The Connection Song List

THE CONNECTION SONG LIST Thank you for downloading our song list! Which specific songs we perform at any given event is based on 3 factors: 1) Popular music that will create an unforgettable party. We “read” your crowd and all the age groups in attendance, calling songs accordingly. 2) General musical styles that fit into your personal preferences. 3) What we perform best; songs that help to make us who we are. We don’t work with pre-determined set lists, but we will try to include many of your preferences & favorites. This in addition to you choosing all the material for any formal dances. We’ll also learn two new songs for you that are not a regular part of our repertoire! (formal dances take precedence). Top 40 Song Title Artist Silk Sonic Leave The Door Open The Weeknd Blinding Lights Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande Rain On Me Kygo & Whitney Houston Higher Love Harry Styles Watermelon Sugar Dua Lipa Don't Start Now Lizzo Juice Lizzo Truth Hurts Lil NasX ft. Billy Ray Cyrus Old Town Road Jonas Brothers Sucker The Blackout Allstars / Cardi B I Like It Like That Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper Shallow Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey The Middle Luis Fonsi Despacito Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars That's What I Like Bruno Mars Ft. Cardi B Finesse Camila Cabello Havana Dua Lipa, Calvin Harris One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Ed Sheeran Shape Of You Shawn Mendes There's Nothing Holding Me Back Clean Bandit Rockabye Niall Horan Slow Hands Sia Cheap Thrills Ariana Grande Thank U, Next Drake One Dance The Chainsmokers Closer -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT on most significant events of 2014 radio year and core trends in streaming broadcast and music industry' development of 2015 Part 1 – RADIO STARS & RADIO HITS ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ”, 127018 РОССИЯ, МОСКВА, СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, ДОМ 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 111, +7 (495) 645 78 55, +44 20 7193 7003, +1 (347) 274 88 41, +49 69 5780 1997, WWW.TOPHIT.RU CONTENTS Introduction.………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Radio stars and radio hits…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Artists and songs – Top Hit Music Awards 2015 winners…….…………………………………………………….……… 6 Achievements of record labels in 2014…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Top 10 of Companies with biggest number of spins on radio air……………………..……………………………….. 8 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on radio air …………………………………………………………. 9 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of spins per each song………………………………………………………. 10 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on TOP HIT 100 radio chart…………………………………. 11 Top 10 Companies with best song test results …………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Top 100 of most frequently rotated local and foreign songs on Moscow radio air 2014…………………… 13 Top 20 of hot rotation playlists, set music trends on Moscow radio air 2014.…………………………………… 15 2015: Top Hit 3.0 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 About the author……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 1 ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ” 125130 РОССИЯ МОСКВА СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 102 +7 495 645 7855 +44 20 7193 7003 +1 347 274 8841 +49 69 5780 1997 WWW.TOPHIT.RU Introduction Every day hundreds of millions of people listen to radio, driving their cars. Music, news, programs and advertising are delivered in single information flows to listeners. Today the radio air brodcast is gradually replaced by the Internet streaming, and the place of customary radiostations and TV sets is more often taken by desktops, tablet PCs and smartphones with various entertainment apps in them. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. MSR SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Hello Rolling in the Deep Someone Like You Alicia Keys Underdog Andra Day Rise Up Ariana Grande 7 Rings Breathin Problems Thank You Next Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Blink 182 All the Small Things Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Just the Way You Are Locked Out of Heaven That's What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B I Like It Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don’t Let Me Down Chris Brown Look at Me Now Clean Bandit Rather Be Echosmith Cool Kids Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God’s Plan Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Toosie Slide Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gotye Somebody That I Used to Know Halsey Without Me Icona Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Radioactive Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want