James Coolidge Carter and the Anticlassical Jurisprudence of Anticodification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Organic Law and Government. Form #11.217

American Organic Law By: Freddy Freeman American Organic Law 1 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. 12/12/2017 EXHIBIT:___________ Revisions Notes Updates to this release include the following: 1) Added a new section titled “From Colonies to Sovereign States.” 2) Improved the analysis on Declaration of Independence, which now covers the last half of the document. 3) Improved the section titled “Citizens Under the Articles of Confederation” 4) Improved the section titled “Art. I:8:17 – Grant of Power to Exercise Exclusive Legislation.” This new and improved write-up presents proof that the States of the United States Union were created under Article I Section 8 Clause 17 and consist exclusively of territory owned by the United States of America. 5) Improved the section titled “Citizenship in the United States of America Confederacy.” 6) Added the section titled “Constitution versus Statutory citizens of the United States.” 7) Rewrote and renamed the section titled “Erroneous Interpretations of the 14th Amendment Citizens of the United States.” This updated section proves why it is erroneous to interpret the 14th Amendment “citizens of the United States” as being a citizenry which in not domiciled on federal land. 8) Added a new section titled “the States, State Constitutions, and State Governments.” This new section includes a detailed analysis of the 1849 Constitution of the State of California. Much of this analysis applies to all of the State Constitutions. American Organic Law 3 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. -

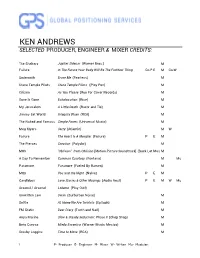

Ken Andrews Selected Producer, Engineer & Mixer Credits

KEN ANDREWS SELECTED PRODUCER, ENGINEER & MIXER CREDITS: The Shelters Jupiter Sidecar (Warner Bros.) M Failure In The Future Your Body Will Be The Furthest Thing Co-P E M Co-W Underoath Erase Me (Fearless) M Stone Temple Pilots Stone Temple Pilots (Play Pen) M Citizen As You Please (Run For Cover Records) M Gone Is Gone Echolocation (Rise) M My Jerusalem A Little Death (Razor and Tie) M Jimmy Eat World Integrity Blues (RCA) M The Naked and Famous Simple Forms (Universal Music) M Meg Myers Sorry (Atlantic) M W Failure The Heart Is A Monster (Failure) P E M The Pierces Creation (Polydor) M M83 "Oblivion" from Oblivion [Motion Picture Soundtrack] (Back Lot Music)M A Day To Remember Common Courtesy (Fontana) M Mu Paramore Paramore (Fueled By Ramen) M M83 You and the Night (Naïve) P E M Candlebox Love Stories & Other Musings (Audio Nest) P E M W Mu Arsenal / Arsenal Lokemo (Play Out!) Unwritten Law Swan (Surburban Noise) M Settle At Home We Are Tourists (Epitaph) M FM Static Dear Diary (Tooth and Nail) M Anya Marina Slow & Steady Seduction: Phase II (Chop Shop) M Beto Cuevas Miedo Escenico (Warner Music Mexico) M Crosby Loggins Time to Move (RCA) M 1 P- Producer E- Engineer M- Mixer W- Writer Mu- Musician KEN ANDREWS SELECTED PRODUCER, ENGINEER & MIXER CREDITS: Empyr Peaceful Riot (Jive) P E M W Mu Nine Inch Nails The Slip Live (The Null Corporation) M Thousand Foot Krutch The Flame In All Of Us (Tooth and Nail) P E M Army of Anyone Army of Anyone (Machine Shop) M Future of Forestry Future of Forestry (Credential) P M Bullets and Octane In -

RED BANK REGISTER Ulued Weeklj

All the Newt ol BED BATH and Surrounding Town* fold Fearlessly and Without Blaa, RED BANK REGISTER Ulued Weeklj. Entored a. S«cond-Oln«« Mutloi at.fho foot- Subscription Prlcji Ons Iiu t2.00. VOLUME LVII, NO..45. offlc« at Rod Bank, N. J.. under the Act of Much' 1. 1870. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, MAY 2, 1935. Sii Monthi SI.00. Simile Cop? <«. PAGES 1. TO 12. 1 Quadrangle Play Coming Illustrated SIGNS Ol' 11EC0VJSUY. ! J AI.K ON CHINA. Dr.AxtellToStay; A Fine New House Good News About lteul Estate Con- HealtB Center Ball Shrewsbury Foreign Missionary So- Tomorrow Night Lecture On Africa ditlonH At Belford. ciety To Hold Tea May 'J. Mr. Steinle To Go J. Crawford Compton of BaygJdii The Foreign Missionary society of Near Tinton Falls Margaret Carson Hubbard to Holghtu, near Bolt'ord, who la cn- Went Over "Big Guns" e Shrewsbury Presbyterlan church The Board of Education of Mid- "Big Hearted Herbert" to be Pre- gagod in thn real estate busjnctiH nnd will hold a tea on the aflcrnonn of It is Being Built for Mrt. Violet sented by Amateur Playert— Talk on Something New in who in the owner of tjovora! develop- Thursday, May 0, in thr Sund.iy- dletown Township So Decided Glemby of New York on Land! : Mra. Matthew Greig Headi Courage Regarding Her Per-ment a, atattiH ' that iiu fur us he schonl loom a! Ihu Shrewsbury Last Thursday — Insurance Which She Recently Bought known thorn IH no house In Belford Event at the Molly Pitcher Hotel Saturday Night Was church . -

Adultery, Law, and the State: a History Jeremy D

Hastings Law Journal Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1986 Adultery, Law, and the State: A History Jeremy D. Weinstein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeremy D. Weinstein, Adultery, Law, and the State: A History, 38 Hastings L.J. 195 (1986). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol38/iss1/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Note Adultery, Law, and the State: A History If your subject is law, the roads are plain to anthropology .... It is perfectly proper to regard and study the law simply as a great anthro- pological document.* Our legal system is to a large extent the product of the reaction of authority to the seeking of private vengeance by wronged parties. To ensure social control, the state must assert a monopoly of force, prohibit- ing its use by any other than itself.1 This monopoly of force is achieved through law. Law, by making the use of force a monopoly of the com- munity, pacifies the community.2 A monopolization of violence is achieved by the gradual institutionalization of vengeance through law. "Institutionalization of vengeance" refers to the process by which violent revenge comes to be exercised lawfully only by the state or under its authority; in other words, violent revenge becomes part of the law by being exercised only at the behest of the state. -

Is There a Law Instinct?

Washington University Law Review Volume 87 Issue 2 2009 Is There a Law Instinct? Michael D. Guttentag Loyola Law School Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Michael D. Guttentag, Is There a Law Instinct?, 87 WASH. U. L. REV. 269 (2009). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol87/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS THERE A LAW INSTINCT? MICHAEL D. GUTTENTAG ABSTRACT The widely held view is that legal systems develop in response to purposeful efforts to achieve economic, political, or social objectives. An alternative view is that reliance on legal systems to organize social activity is an integral part of human nature, just as language and morality now appear to be directly shaped by innate predispositions. This Article formalizes and presents evidence in support of the claim that humans innately turn to legal systems to organize social behavior. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 270 I. THE LAW INSTINCT HYPOTHESIS ......................................................... 276 A. On the Three Essential Features of a Legal System ................ 277 1. Distinguishing Legal Systems from Other Types of Normative Behavior......................................................... 279 2. Distinguishing the Law Instinct Hypothesis from Related Claims ................................................................ 280 3. The Normativity of Law ................................................... 281 4. The Union of Primary Rules and Secondary Rules ......... 282 5. -

Grammy Countdown U2, Nelly Furtado Interviews Kedar Massenburg on India.Arie Celine Dion "A New Day Has Come"

February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 $6.00 GRAMMY COUNTDOWN U2, NELLY FURTADO INTERVIEWS KEDAR MASSENBURG ON INDIA.ARIE CELINE DION "A NEW DAY HAS COME" The premiere single from "A New Day Has Come," her first new album in two years and her first studio album since "Let's Talk About Love," which sold over 28 million copies worldwide. IMPACTING RADIO NOW 140 million albums sold worldwide 2,000,000+ cumulative radio plays and over 21 billion in combined audience 6X Grammy' winner Winner of an Academy Award for "My Heart Will Go On" Extensive TV and Press to support release: Week of Release Jprah-Entire program dedicated to Celine The View The Today Show CBS This Morning Regis & Kelly Upcoming Celine's CBS Network Special The Tonight Show Kicks off The Today Show Outdoor Concert Series Single produced by Walter Afanasieff and Aldo Nova, with remixes produced by Ric Wake, Humberto Gatica, and Christian B. Video directed by Dave Meyers will debut in early March. Album in stores Tuesday, March 26 www.epicrecords.com www.celinedion.com I fie, "Epic" and Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off. Marca Registrada./C 2002 Sony Music Entertainment (Canada) Inc. hyVaiee.sa Cartfoi Produccil6y Ro11Fair 1\lixeJyJo.serli Pui3 A'01c1 RDrecfioi: Ron Fair rkia3erneit: deter allot" for PM M #1 Phones WBLI 600 Spins before 2/18 Impact Early Adds: KITS -FM WXKS Y100 KRBV KHTS WWWQ WBLIKZQZ WAKS WNOU TRL WKZL BZ BUZZWORTHY -2( A&M Records Rolling Stone: "Artist To Watch" feature ras February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher LENNY BEER THE DIVINE MISS POLLY Editor In Chief EpicRecords Group President Polly Anthony is the diva among divas, as Jen- TONI PROFERA Executive Editor nifer Lopez debuts atop the album chart this week. -

Unwritten Mp3 Free Download Unwritten PDF Book by Charles Martin (2013) Download Or Read Online

unwritten mp3 free download Unwritten PDF Book by Charles Martin (2013) Download or Read Online. Unwritten PDF book by Charles Martin Read Online or Free Download in ePUB, PDF or MOBI eBooks. Published in 2013 the book become immediate popular and critical acclaim in fiction, christian fiction books. The main characters of Unwritten novel are John, Emma. The book has been awarded with Booker Prize, Edgar Awards and many others. One of the Best Works of Charles Martin. published in multiple languages including English, consists of 368 pages and is available in ebook format for offline reading. Unwritten PDF Details. Author: Charles Martin Book Format: ebook Original Title: Unwritten Number Of Pages: 368 pages First Published in: 2013 Latest Edition: May 7th 2013 Language: English Generes: Fiction, Christian Fiction, Christian, Romance, Contemporary, Novels, Inspirational, Romance, Contemporary Romance, Drama, Adult Fiction, Formats: audible mp3, ePUB(Android), kindle, and audiobook. The book can be easily translated to readable Russian, English, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Malaysian, French, Portuguese, Indonesian, German, Arabic, Japanese and many others. Please note that the characters, names or techniques listed in Unwritten is a work of fiction and is meant for entertainment purposes only, except for biography and other cases. we do not intend to hurt the sentiments of any community, individual, sect or religion. DMCA and Copyright : Dear all, most of the website is community built, users are uploading hundred of books everyday, which makes really hard for us to identify copyrighted material, please contact us if you want any material removed. Unwritten Read Online. Please refresh (CTRL + F5) the page if you are unable to click on View or Download buttons. -

Unwritten Law- Cailin Free Download Album Version Unwritten Law

unwritten law- Cailin free download album version Unwritten Law. More of a power pop band than anything else, though they're nestled in Southern California's skate/snowboard punk scene, Unwritten Law was formed in 1990 by then 12 year old drummer Wade Youman, bassist Craig Winters, guitarist Matt Rathje, and vocalist Chris Mussey. Following a number of line-up changes, the group eventually coalesced around Youman, vocalist Scott Russo, guitarists Rob Brewer and Steve Morris, and bassist John Bell; releasing their first two albums under this line-up. After another series of line-up changes, the line-up is currently Scott Russo on vocals, Wade Youman on drums, Chris Lewis (formerly of Fenix TX) on guitar, and Jonny Grill (Scott Russo's younger brother) on bass. Scott Russo: 1992 - Current Chris Mussey: 1990 - 1991. Chris Lewis: 2014 - Present Ace Von Johnson: 2013 - 2014 Kevin Besignano: 2011 - 2013 Steve Morris: 1994 - 2011 Rob Brewer: 1992 - 2005 Matt Rathje: 1990 - 1991. Jonny Grill: 2013 - Current Derik Envy: 2011 - 2013 Pat "PK" Kim: 1998 - 2011 Micah Albao: 1998 [Recording of Self-Titled album only] John Bell: 1993 - 1997 Jeff Brehm: 1990 - 1992 Craig Winters: 1990. Drummers Wade Youman: 1990 - 2004, 2013 - Current Dylan Howard: 2008 - 2013 Tony Palermo: 2005 - 2008. The following additional people were mentioned to have been previous members of Unwritten Law by Wade Youman in a February 3, 2005 interview: - Eric Barth - Nathan Rooney - Shannon Woods - Donald Stone - Jason Hill - Vince "Sloppo" Cailin. And girl it breaks my heart when I have to see you cry So many things I want to say yea now I know that your the reason That I'm here today whenever your here just stay near we'll be alright Yea alright hey little girl look what you do oh I love you Hey little girl look what you do and you do. -

The Modern Common Law of Crime

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 111 Issue 2 Article 2 Spring 2021 The Modern Common Law of Crime Robert Leider Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Leider, The Modern Common Law of Crime, 111 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 407 (2021). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/21/11102-0407 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 111, No. 2 Copyright © 2021 by Robert Leider Printed in U.S.A. THE MODERN COMMON LAW OF CRIME ROBERT LEIDER* Two visions of American criminal law have emerged. The first vision is that criminal law is statutory and posits that legislatures, not courts, draft substantive criminal law. The second vision, like the first, begins with legislative supremacy, but it ends with democratic dysfunction. On this view, while contemporary American criminal law is statutory in theory, in practice, American legislatures badly draft and maintain criminal codes. This effectively delegates the “real” drafting of criminal law to prosecutors, who form the law through their charging decisions. This Article offers a third vision: that modern American criminal law is primarily conventional. That is, much of our criminal law is defined by unwritten common-law-like norms that are widely acknowledged and generally respected, and yet are not recognized as formal law enforceable in courts. -

Von at Het Ithity- TV Marriage Fo the Mu Ic Industry? Howie Ut Authenticity

[;i:ii»Tdw PIJ »Tel Widl'113 www.fmqb.com October 1, 1999 von at het Ithity- TV Marriage 00 fo the Mu ic Industry? Howie ut Authenticity Oh The „om ggw Statioli 4tor ea> a 11Nie. 4 illeak-'4 1 Instantly Makes Phones Come Alivi?!!! N e-e""ail lied) II LW II lee 111!""beZIF TVPIE Z I • r îgi ell LU 41,273 Pieces feK Scanned This Week! Billboard D-39' qm. Featuring OZZY! ONIHIA1:13A 90.000 Pieces Over 300,000 The first single from World Coming Down Scanned In 21 Days! Shipped! Album in stores Now frnqb Active Rock: 44 -37' Over 100 Stations In On Impact Day In Multiple Formats!!! Active Rock Monitor 36 -33' à ••arrniz,, 0 Top 5 Most Added 2 Weeks In-A-Row! R&R Active Rock: 36 -33' th Moir re : ROADRUNNER Dunn Now On The Management: Sharon Osbourne Management •Produced by lush Abraham •Mixed by Dave "Rave" Ogl Top 5 Phones: WZTA, KUPD o 0 1999 Roadrunner aesenIrx. www roadrunnemmenkral •IRMILCOSICAMINIOElee Top 10 Phones: WAAF, WLZR, WKLQ U 01110M Produced by Save - ep....4 Headline Tour Beginning 9/29 ReProcluceci by S sole ami r vateit Management: Andy C Add and , , , •.. i• r• •r• 5 corn Rob McDermott for A 1M 0 Ms Roadrunner Record ROADRUNNER E G CD RIDS IstIA HINE HEAD THE SHEIge 'nett THE SHEILA DI IINE p' The first single from the new album 'HIE BURNING RED WFNX 25x WBCN 12x New Adds: KSJO, KHOP WKRL 26x KWOD 22x •oks" KJEE 18x WAVF 17x Over 50 Stations Including: Pulse Y107 15x WAAF 16X 224 Pieces, Rank 116 WOXY 17x "Smashingly M odic" WXRK 5X 359 Pieces KTCL 15x KRAD 14x -The Boston lobe KXXR 11X 150 Pieces WROX 14x WRAX 12x PHOOUCF0 BY ROSS ROBINSON FOR I Artt KBPI 17X 105 Pieces KNRK 12x & MANY MORE http://www.theshei orne corn PAANACEMENT. -

Suyer May Plead ''Unwritten

SUYER MAY PLEAD Thousands Flock To Morgrue; Fail To Identify Trio BOARD WITHOUT MALTBIE PROPOSES POWER TO A a ‘‘UNWRITTEN LAW A COUNTY SYSTEM ONCH^JOB Stadeot Cleric Shooto His PLAN OF TOWN Appointee, Mrs. G. T. WiO- FOR STATE COURTS Girl Bride and Priest in son, WiU Continne— Dis- STORE TABLED Chief Justice of State Sb* New York H6teL After DOMESTIC STRIFE close Manchester FERA Drinkinc Boot— Attorney BYSQICTMEN preme Court Would Re- FEARED IN REICH Men Work EIsevYhere. moye AO Political Control Plans Jostilication De- Cost for Operating Store Powerless to do, anything about fense-^ Yoant Wif e, Hol- Hitler Believes Rivnl Military from Minor Tribunals -r* Would Be $4,000 to the appointment of Mrs. George T. Willson of Wapping aa an investiga- lywood Dancer, Prompted Organization WQl Start One Plan WonU Hare the / $5,000 a Year— Action tor for the local charity department, because o f circumstances centering Pdrehase of Weapon. Trouble in Near Future. Judges of Superior Court on Local Water Bonds. about the F E R A which are beyond their control, the Selectmen last night took no action on the matter. Make the Selections. New York, Nov. 37.— (A P )— Dl- Berlin, Nov. 27.— (A P )—The Mrs. Willson will continue her work /sheveled and apparently on the After nearly eight hours of con- German army and the natiob’s po- here at a salary of $125 a month and / verge o f complete collapse, Joseph tinuous discussion on several im- lice forces are operating under a New Haven, Nov. 21—(A P )—Re- automobile expenses of seven cents portant subjects, the Board of a mile. -

Choraliers Take Flight in Concert

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 2002 WWW.THESPAR1 NDA I IN.CONI TURF' WARS Rugby clubs, intrumerial leagues are displaced by new turf laid down at South Campus Sports, 3 TAN AUNRAVEI. ACITIZIti COPE S DEB1.11 Minal Gandhi advises Self-titled album features blues, ladies to keep their VoL. 118 hip-hop, jazz and urban beats. 70' clothes on and their A & E, 7 n.t..4 dignity intact No. 18 t, i Opinion, 2 V 1180 IN TODAY S ISSUE Opinion 2 Sports 3 Classified... 7 AIL Sparta Guide 2 Crossword 7 A & E 8 Si It% I N(p S Vs' jOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 Choraliers take flight in concert Tickets By Michelle Giluso anger DAILY STAEF WRITER A scream echoed throughout the Prince of Peace Lutheran Church on Sunday evening in students Saratoga. Two loud bangs soon fol- lowed. By Lori Hanley These weren't the sounds of DAILY STAFF WRITER a crime being committed. They were the sounds of the A San Jose State University San Jose State University student said he is furious after Choraliers performing receiving a $31 parking citation one of for parking their most unusual and enter- illegally in the 10th taining songs of their "Aloha Street garage. "I'm outraged. Nobody can find parking without circling for an hour. So you are late for REVIEW classes (and) miss quizzes," said Concert" program, senior Mohammad Shobeiri. "Pamugun." Shobeiri said he arrived on In Tagalog, a Filipino dialect, the SJSU Choraliers impres- campus at 8 a.m. on Feb. 12 and sively sang composer circled the sixth floor of the 10th Francisco Street garage looking for a park- Feliciano's song, which tells the tale of a ing place for about an hour sparrow's desperate before parking illegally in a cor- attempts to escape from danger.