Early Governance in the Muslim Umma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Edition the the Prophet of Mercy Muhammad, May Allah’S Peace and Blessings Be Upon Him Dawn

The Newsletter of the Birmingham Mosque Trust Ltd. Dhul Qadah/Dhul Hijjah 1434 Issue No. 256 Special Edition The The Prophet of Mercy Muhammad, May Allah’s Peace and Blessings be upon him Dawn history who was supremely successful on both the religious and secular levels." (The 100: A ranking of the most influential persons in history" New York, 1978, p. 33) The well known British historian, Sir William Muir, in his "Life of Mohammed" adds: “Our authorities, all agree in ascribing to the youth of Mohammad a modesty of deportment and purity of manners rare among the people of Makkah... The fair character and honourable bearing of the unobtrusive youth won the approbation of his fellow-citizens; and he received the title, by common consent, of Al-Ameen, the Trustworthy." Message Of the Prophet: The celebrated British writer, Thomas Carlyle, in his book On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History-, observes: We Love Muhammad "Ah on: this deep-hearted son of the wilderness with his "You have indeed in the Messengers of God an excellent beaming black eyes and open social deep soul, had other exemplar, for any one whose hope is in God and the Final thoughts than ambition. A silent great man; he was one of Day, and who engages much in the glorification of the those who cannot but be in earnest; whom Nature herself has Divine." [Quran 33:21] appointed to be sincere. While others walk in formulas and hearsays, contented enough to dwell there, this man could not screen himself in formulas; he was alone with his own What do they (Non-Muslims) soul and the reality of things. -

Marriage to Umm Habiba Tension in Mecca Had Reached Its Peak

limited the number of women a man could marry - the customary practice in pre-Islamic Arabia - and encouraged monogamy, allowed for God’s Messenger to marry several women in order for him to reach all his addressees in their entirety within as short a time as twenty-three years. The Messenger of God made use of this means in loosening such closely knit ties at a time when all the doors on which he knocked were slammed shut in his face. Moreover, it is not possible to suppose that the marriages of God’s Messenger, who stated, “God has assuredly willed that I marry only those who are of Paradise,”339 and who took his each and every step in line with the Divine injunctions, could be realized except by God's permission. Within this context, he states: “Each of my marriages and those of my daughters was conducted as a result of Divine permission conveyed to me through Gabriel.”340 In this way was he able to come together, on the basis of kinship, with those people who were not capable of being approached, and it was in these assemblies that the hearts of those who were consumed with hatred and enmity were softened. The marriages of God’s Messenger functioned as a bridge in his communication with them, and served to relax the atmosphere as well as legitimize his steps in their regard. He extended hospitality towards them, invited them to his wedding feasts using his marriages as a means to come together, and sent them gifts, drawing attention to their affinity. -

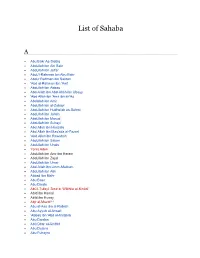

List of Sahaba

List of Sahaba A Abu Bakr As-Siddiq Abdullah ibn Abi Bakr Abdullah ibn Ja'far Abdu'l-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr Abdur Rahman ibn Sakran 'Abd al-Rahman ibn 'Awf Abdullah ibn Abbas Abd-Allah ibn Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As Abdallah ibn Amir Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi Abdullah ibn Jahsh Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Suhayl Abd Allah ibn Hanzala Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah Abdullah ibn Salam Abdullah ibn Unais Yonis Aden Abdullah ibn Amr ibn Haram Abdullah ibn Zayd Abdullah ibn Umar Abd-Allah ibn Umm-Maktum Abdullah ibn Atik Abbad ibn Bishr Abu Basir Abu Darda Abū l-Ṭufayl ʿĀmir b. Wāthila al-Kinānī Abîd ibn Hamal Abîd ibn Hunay Abjr al-Muzni [ar] Abu al-Aas ibn al-Rabiah Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib Abu Dardaa Abû Dhar al-Ghifârî Abu Dujana Abu Fuhayra Abu Hudhaifah ibn Mughirah Abu-Hudhayfah ibn Utbah Abu Hurairah Abu Jandal ibn Suhail Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir Abu Musa al-Ashari Abu Sa`id al-Khudri Abu Salama `Abd Allah ibn `Abd al-Asad Abu Sufyan ibn al-Harith Abu Sufyan ibn Harb Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Abu Zama' al-Balaui Abzâ al-Khuzâ`î [ar] Adhayna ibn al-Hârith [ar] Adî ibn Hâtim at-Tâî Aflah ibn Abî Qays [ar] Ahmad ibn Hafs [ar] Ahmar Abu `Usayb [ar] Ahmar ibn Jazi [ar][1] Ahmar ibn Mazan ibn Aws [ar] Ahmar ibn Mu`awiya ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Qatan al-Hamdani [ar] Ahmar ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Suwa'i ibn `Adi [ar] Ahmar Mawla Umm Salama [ar] Ahnaf ibn Qais Ahyah ibn -

Muhammad Peace and Blessings Be Upon Him

Prophethood and Prophet Muhammad peace and blessings be upon him İsmail Büyükçelebi Copyright © 2004 by The Light, Inc. & Işık Yayınları Second Impression All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, inclu- ding photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by The Light, Inc. 26 Worlds Fair Dr. Somerset, NJ 08873 USA e-mail: [email protected] www.thelightpublishing.com Translated from Turkish by Ali Ünal ISBN 1-932099-57-3 Printed by Güzel Sanatlar Matbaası A.Ş. Istanbul, Turkey September 2004 2 The Meaning of Prophethood and the Prophets’ Mission God creates every community of beings with a purpose and a guide or a leader. It is inconceivable that God Almighty, Who gave bees a queen, ants a leader, and birds and fish each a guide, would leave us without Prophets to guide us to spiritual, intellectual, and mate- rial perfection. Prophethood is the highest rank and honor that a human can receive from God. It proves the superiori- ty of that human’s inner being over all others. A Prophet is like a branch arching out from the Divine to the human realm. He is the very heart and tongue of creation, and possesses a supreme intellect that penetrates into the reality of things and events. Moreover, he is the ideal being, for all of his Prophethood is the high- faculties are harmoni- est rank and honor that ously excellent and ac- a person can tive. -

The Prophet's Noble Character

The Prophet's Noble Character www.rasoulallah.net The Prophet's Noble Character www.rasoulallah.net Contents How did Prophet Muhammad Achieve Reform? ....................................................... 6 The Exemplary Justice of the Prophet .................................................................... 11 His Manners and Disposition ................................................................................. 14 Justice .............................................................................................................. 16 Love for the Poor ................................................................................................. 17 Can Prophet Muhammad be taken as a Model for Muslims to follow? .............................. 18 Did Prophet Muhammad Perform Miracles? ......................... ................................. 19 How the Prophet Instilled Brotherhood among Muslims ........................................... 20 The Truth about Muhammad ................................................................................ 22 The Forgiveness of Muhammad Shown to Non-Muslims .......................................... 25 The Prophet and Uniting the Muslim Ummah .......................................................... 28 The Simple Life of Muhammad .............................................................................. 30 www.rasoulallah.net How did Prophet Muhammad Achieve Reform? Reform has become today’s fashionable issue. Everyone is demanding reform although many are not ready for its consequences. -

The Forgiveness of Muhammad Shown to Non-Muslims (Part 2 of 2)

The Forgiveness of Muhammad Shown to Non-Muslims (part 2 of 2) Description: The forgiveness of the Prophet towards non-Muslims, even those who sought to kill him and opposed his mission throughout his life. Part 2: More examples. By M. Abdulsalam (© 2006 IslamReligion.com) Published on 27 Feb 2006 - Last modified on 06 May 2014 Category: Articles >The Prophet Muhammad > His Characteristics Category: Articles >Current Issues > Islam and Non-Muslims The mercy of the Prophet even extended to those who brutally killed and then mutilated the body of his uncle Hamzah, one of the most beloved of people to the Prophet. Hamzah was one of the earliest to accept Islam and, through his power and position in the Quraishite hierarchy, diverted much harm from the Muslims. An Abyssinian slave of the wife of Abu Sufyan, Hind, sought out and killed Hamzah in the battle of Uhud. The night before the victory of Mecca, Abu Sufyan accepted Islam, fearing the vengeance of the Prophet, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him. The latter forgave him and sought no retribution for his years of enmity. After Hind had killed Hamzah she mutilated his body by cutting his chest and tearing his liver and heart into pieces. When she quietly came to the Prophet and accepted Islam, he recognized her but did not say anything. She was so impressed by his magnanimity and stature that she said, "O Messenger of God, no tent was more deserted in my eyes than yours; but today no tent is more lovely in my eyes than yours." Ikrama, son of Abu Jahl, was a great enemy of the Prophet and Islam. -

The Vision of Islam Maulana Wahiduddin Khan

The Vision of Islam Maulana Wahiduddin Khan GOODWORD BOOKS Translated by Farida Khanam First published 2014 This book is copyright free. Goodword Books 1, Nizamuddin West Market, New Delhi-110 013 Tel. +9111-4182-7083, +918588822672 email: [email protected] www.goodwordbooks.com Goodword Books, Chennai 324, Triplicane High Road, Triplicane, Chennai-600005 Tel. +9144-4352-4599 Mob. +91-9790853944, 9600105558 email: [email protected] Goodword Books, Hyderabad 2-48/182, Plot No. 182, Street No. 22 Telecom Nagar Colony, Gachi Bawli Hyderabad-500032 Mob. 9448651644 email: [email protected] Islamic Vision Ltd. 426-434 Coventry Road, Small Heath Birmingham B10 0UG, U.K. Tel. 121-773-0137 e-mail: [email protected] www.islamicvision.co.uk IB Publisher Inc. 81 Bloomingdale Rd, Hicksville NY 11801, USA Tel. 516-933-1000 Toll Free: 1-888-560-3222 email: [email protected] www.ibpublisher.com Printed in India Contents § Foreword — 5 Foreword 2 — 8 CHAPTER ONE The Essence of Religion — 9 Worship — 9 The Demands of Worship — 15 Witness to Truth — 23 CHAPTER TWO The Four Pillars — 30 Fasting — 32 Prayer (Salat) — 37 Zakat — 43 Pilgrimage (Hajj) — 48 CHAPTER THREE The Straight Path — 58 What is the straight path? — 58 The Straight Path of the Individual — 62 The Straight Path of Society — 66 The Principle of Divine Succour — 69 3 CHAPTER FOUR Seerah as a Movement — 71 The Beginning of Dawah — 72 The Language of Dawah — 76 The Aptitude of the Arabs — 79 The Universality of Dawah — 82 Factors Working in Favour of Dawah —86 Reaction to the Message of Islam — 89 Expulsion from the Tribes — 96 Emigration — 100 Victory of Islam — 107 CHAPTER FIVE Calling People to Tread the Path of God — 115 The Significance of Calling People to Tread the Path of God — 115 Content of the Call — 121 CHAPTER SIX Modern Possibilities — 126 CHAPTER SEVEN F i n a l W o rd — 143 Index — 148 4 Foreword § In Story of an African Farm, Olive Schrieiner (1855-1920) a noted South African novelist, recounts the story of a hunter who goes in search of the beautiful White Bird of Truth. -

Seerat Un Nabi Vol II (English )

GOVFRNMfNT OF INDIA mCHMOlOGtUL SURVEY OF INDIA ,, Central Archaeological Library NEW DELHI acc wo, 70843 i:Ai,t. no MullNuV SIRAT-UN-NABI [THE LIFE OF THE PROPHET] f^a.-m-n^ (peace be upon him) Volume II O i 9 % k* •ALLAMA SHIBLI NU'MANI Rendered Into English by M. TAYYIB BAKHSH BUDAYUNI IDARAH-I ADABIYAT-I DELLI 2009 QASIMJAN ST DELHI (INDIA) IAD RELIGIO-PHILOSOPHY (REPRINT) SERIES NO. 36 fofST H :: jjf^'17 » First Published 1979 Reprint 1983 Price RS. 70 >I PRINTED IN INDIA PUBLISHED BY MOHAMMAD AHMAD FOR IDARAH-I ADBIYAT-I DELLI, 2009, QASIMJAN ST., DELHI-6 AND PRINTED AT JAYYED PRESS, BALLIMARAN, DELHI-6. r 7oFV3 CONTENTS Page PREFACE ... vii Ghazwat—The Battle of Badr 1. Expeditions Preceding Badr 6 2. The Battle of Badr ... 11 3. The Battle of Badr spoken in the Qur'Sn ... 31 4. A Review of the Battle of Badr ... 35 5. The Real Cause of the Ghazwa of Badr ... 49 6. An Essential Point ... 52 7. Consequences of Badr ... 53 8. Ghazwa of Sawiq ... 54 9. Marriage of Eatima ... 55 10. Miscellaneous Events ... 57 Ghazwa Uhud 11. Ghazwa Uhud ... 58 '.8. Miscellaneous Events ... 75 Ghazwat and Saraya 13. Sirya Abi Salama ... 77 i. Sirya Ibn Unais ... 77 .5. Sirya Bi'r Ma'flna ... 77 16. Sirya Raji* ... 79 17. Miscellaneous Happenings ... 82 (it,) Treaty and War 18. Treaty and War with the Jews ... 83 19. Ghazwa Baai Qainuqa' ... 90 20. Murder of Ka'b Ibn Ashraf ... 91 21. Ghazwa Bani Nadir ... 94 Ghazwa Morisi', Event of Ifk and Ghazwa Ahzat 22. -

Malik's Muwatta Table of Contents

Malik's Muwatta Table of Contents Malik's Muwatta..............................................1 Introduction to Translation of Malik's Muwatta...............2 Book 1: The Times of Prayer..................................3 Book 2: Purity..............................................11 Book 3: Prayer..............................................41 Book 4: Forgetfulness in Prayer.............................62 Book 5: Jumu'a..............................................63 Book 6: Prayer in Ramadan...................................71 Book 7: Tahajjud............................................74 Book 8: Prayer in Congregation..............................82 Book 9: Shortening the Prayer...............................91 Book 10: The Two 'Ids......................................114 Book 11: The Fear Prayer...................................117 Book 12: The Eclipse Prayer................................119 Book 13: Asking for Rain...................................123 Book 14: The Qibla.........................................126 Book 15: The Qur'an........................................130 Malik's Muwatta Table of Contents Book 16: Burials...........................................145 Book 17: Zakat.............................................160 Book 18: Fasting...........................................190 Book 19: I'tikaf in Ramadan................................210 Book 20: Hajj..............................................217 Book 21: Jihad.............................................296 Book 22: Vows and Oaths....................................316 -

The Fiqh of Menstruation

Page | 1 Advanced Level Topics of Study for: Core Sunni Doctrines (Aqeda) Page | 2 Page | 3 Contents 1. Islamic belief in God…………………………………………………….………5 2. “Where” is Allah? Does Allah have a direction ....................................................6 3. The Asma ul Husna………………………………………………………… …... 7 4. ‘Literalism in God’s Attributes’? Al Azhar Fatwa………………….………….16 5. Imam Tahawi’s Aqida Tahawiyya……………………………………………….34 6. Ism al Azam? “Regarding Tawassul” and the “Hadith of the Blind Man…….... 43 7. The Creation of Angels …………………………………………………………44 8. Life of the Prophets in Barzakh.………………………………………………...52 9. The infallibility of Ambiya……………………………….……………………..56 10. The necessity to love the Prophet..........................................................................61 11. The Prophetic Reality is Nur (Light)…...……………………………………... ..69 12. The Prophetic Reality is Hadhir Nadhir (Present and Witnessing)….…………93 13. The Prophet’s Knowledge of the Unseen (Ilm e Ghayb)…………………….…105 14. Belief of the parents of the Prophet Muhammad……………………………….173 15. The beliefs of Abu Talib according to Allamah Shibli Nu’mani……………….173 16. Life of Al Khidr (al Khizr)……………………………………………………...174 17. The Illustrious sons of Fatima Zahra………………………………………….. 180 18. Qadaa and Qadar……………………………………………………………… 188 19. Aakhira, Barzakh, Resurrection and Hisab…………………………………… 188 20. Belief in the Intercession of the Prophet……………………………………… 190 21. The correct Sunni position on belief in the twelve imams?............................... 201 22. The virtues of the Quraysh………………………………………………..……203 23. The significance of Masjid al-Aqsa in Jerusalem…………...………………….212 24. The status of Arabs………………………………………………..…………... 214 25. The sacrificial son of Abraham: Ishmael or Isaac……………………..……… 218 Page | 4 Page | 5 Advanced Level Topics of Study for Core Sunni Doctrines 1. In one paragraph, describe the Islamic belief in God based on the following article. -

A Response to Patricia Crone's Book 3 in the Name of Allah the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful

A Response to Patricia CroneCrone''''ss Book (Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam) By Dr. Amaal Muhammad Al-Roubi A Response to Patricia Crone's Book 3 In the Name of Allah the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. Introduction Patricia Crone's book Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam , Oxford, 1987 grabbed my attention, because it tackled an era connected with "The History of the Arabs before Islam", a course I am teaching to female students at the Department of History, King Abdul-Aziz University, Jeddah. It is noteworthy that when I started reading through this book, I was really shocked by what I read between the lines and even overtly. What shocked me is that some things were clear, but others were grossly incorrect and hidden behind a mask of fake historical research, the purposes of which are obvious for every professional researcher. Therefore, as a scholar in the field, it was necessary for me to respond to this book so that readers will not be deceived and misguided by the great errors introduced to them under the guise of historical research or scholarship. Crone is an orientalist who raised somewhat clever questions, but her answers were misleading. Most of the time, she deliberately used documented and logical coordination in order to prove the opposite of what has already been proven to be correct. It is a well-known fact that the easiest way to pass an illogical issue and to make readers swallow it is to begin by an assumption which looks logical and persuasive, but is in fact essentially void. -

Da* Wain Islamic Thought: the Work Of'abd Allah Ibn 'Alawl Al-Haddad

Da* wa in Islamic Thought: the Work o f'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawl al-Haddad By Shadee Mohamed Elmasry University of London: School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. ProQuest Number: 10672980 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672980 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Imam 'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawi al-Haddad was bom in 1044/1634, he was a scholar of the Ba 'Alawi sayyids , a long line of Hadrami scholars and gnostics. The Imam led a quiet life of teaching and, although blind, travelled most of Hadramawt to do daw a, and authored ten books, a diwan of poetry, and several prayers. He was considered the sage of his time until his death in Hadramawt in 1132/1721. Many chains of transmission of Islamic knowledge of East Africa and South East Asia include his name. Al-Haddad’s main work on da'wa, which is also the core of this study, is al-Da'wa al-Tdmma wal-Tadhkira al-'Amma (The Complete Call and the General Reminder ).