Kingoonya Soil Conservation Board District Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andamooka Opal Field- 0

DECEMBER IS, 1961 C@8 AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM MAGAZINE VoL. XliL No. 12 Price-THREE SHILLINGS The Austra lian Museum's new exhibit of pitchblende, the richest source of the radioactive metal uranium. T his huge specimen (centre), the largest piece of pitchblende ever mined, weighs just on seven-eighths ?f a ton. 1t came. from the El S l~ eran a ~, line , Northern Territory. Specimens of ccruss1te (left) and pectohte. thOUf!h not nuneralog•cally connected with pitchblende, arc displayed with it because of their great size and high quality. Re gistered at the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission as a peri odical. THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM HYDE PARK, SYDNEY BO ARD O F TRUSTEES PRESIDENT: F. B. SPENCER CROWN TRUSTEE: F. B. SPENCER OFFICIAL TRUSTEES: THE HON. THE CHIEF JUSTICE. THE HON. THE PRESIDENT OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. THE HON. THE CHIEF SECRETARY. THE HON. THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL. THE HON. THE TREASURER. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR PUBLIC WORKS. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR EDUCATION. THE AUDITOR-GENERAL. THE PRESIDENT OF THE NEW SOUTH WALES MEDICAL BOARD. THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL AND CHIEF SURVEYOR. THE CROWN SOLICITOR. ELECTIVE TRUSTEES: 0. G. VICKER Y, B.E., M.I.E. (Aust.). FRANK W. HILL. PROF. A. P. ELKIN, M.A., Ph.D. G. A. JOHNSO N. F. McDOWELL. PROF. J . R. A. McMILLAN, M.S., D .Sc.Agr. R. J. NOBLE, C.B.E., B.Sc.Agr., M.Sc., Ph.D. E. A. 1. HYDE. 1!. J. KENNY. M.Aust.l.M.M. PROF. R. L. CROCKER, D.Sc. F. L. S. -

Released Under Foi

File 2018/15258/01 – Document 001 Applicant Name Applicant Type Summary All briefing minutes prepared for Ministers (and ministerial staff), the Premier (and staff) and/or Deputy Premier (and staff) in respect of the Riverbank precinct for the period 2010 to Vickie Chapman MP MP present Total patronage at Millswood Station, and Wayville Station (individually) for each day from 1 Corey Wingard MP October 30 November inclusive Copies of all documents held by DPTI regarding the proposal to shift a government agency to Steven Marshall MP Port Adelaide created from 2013 to present The total annual funding spent on the Recreation and Sport Traineeship Incentive Program Tim Whetstone MP and the number of students and employers utilising this program since its inception A copy of all reports or modelling for the establishment of an indoor multi‐sports facility in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia All traffic count and maintenance reports for timber hulled ferries along the River Murray in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia from 1 January 2011 to 1 June 2015 Corey Wingard MP Vision of rail car colliding with the catenary and the previous pass on the down track Rob Brokenshire MLC MP Speed limit on SE freeway during a time frame in September 2014 Request a copy of the final report/independent planning assessment undertaken into the Hills Face Zone. I believe the former Planning Minister, the Hon Paul Holloway MLC commissioned Steven Griffiths MP MP the report in 2010 All submissions and correspondence, from the 2013/14 and 2014/15 financial years -

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

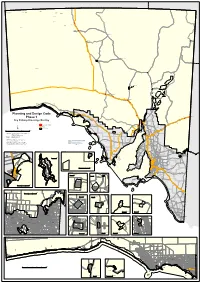

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Naretha Meteorite (Synonyms Kingoonya, Kingooya)

Rec. West. Aust. Mus., 1976, 4 (1) NARETHA METEORITE (Sync;>nyms: Kingoonya, Kingooya) W.H. CLEVERLY* [Received 27 May 1975. Accepted 1 October 1975. Published 31 August 1976.1 ABSTRACT Much of the missing portion of the Naretha (Western Australia) meteorite has been located in museums as an un-named specimen and as two smaller specimens masquerading under the name 'Kingoonya' (or 'Kingooya'). The use of the junior synonyms with their implications of a South Australian site of find should be discontinued. INTRODUCfION Naretha meteorite, an L4 chondrite, was found in 1915 about 3 km north of the 205-mile station during construction of the Trans-Australian Railway. It was broken into at least three major pieces which were acquired by Mr John Darbyshire, Supervising Engineer for the construction of the western end of the railway (construction was proceeding simultaneously from both Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta ends - Fig. 1). Mr Darbyshire donated the meteorite to the W.A. School of Mines in Kalgoorlie where one' piece was retained and exhibited with a photograph of the reassembled meteorite (Fig. 2). A second fragment which was passed on to the Geological Survey of Western Australia was noted briefly by Simpson (1922) who first used the name 'Naretha', the name which had been given to the 205-mile station. There is strong presumptive evidence that the third fragment was passed on to Mr S.F.C. Cook of Kalgoorlie, a private collector from whose inaccurate verbal statements and undocumented collection, the subsequent confusion arose. In late 1926 Mr Cook gave a small piece of 'meteorite to Mr G.W. -

Lake Torrens SA 2016, a Bush Blitz Survey Report

Lake Torrens South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study AD State Herbarium of South Australia ANIC Australian National Insect Collection CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation DEWNR Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (South Australia) DSITI Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation (Queensland) EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) MEL National Herbarium of Victoria NPW Act National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia) RBGV Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria SAM South Australian Museum Page 2 of 36 Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Summary In late August and early September 2016, a Bush Blitz survey was conducted in central South Australia at Lake Torrens National Park (managed by SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources) and five adjoining pastoral stations to the west (Andamooka, Bosworth, Pernatty, Purple Downs and Roxby Downs). The traditional owners of this country are the Kokatha people and they were involved with planning and preparation of the survey and accompanied survey teams during the expedition itself. Lake Torrens National Park and surrounding areas have an arid climate and are dominated by three land systems: Torrens (bed of Lake Torrens), Roxby (dunefields) and Arcoona (gibber plains). -

Body Freezer

BODY IN THE FREEZER the Case of David Szach Acknowledgements I am indebted to editorial comments and suggestions from Jan McInerney, Pat Sheahan, Anthony Bishop, Dr Harry Harding, Michael Madigan, and Dr Bob Moles. Andrew Smart of Blackjacket Studios designed the cover. I especially appreciate the support of my wife, Liz. ISBN: 978-0-9944162-0-9 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Printed in Adelaide by Griffin Press Any enquiries to the author’s email: [email protected] BODY IN THE FREEZER the Case of David Szach TOM MANN Author’s note Following the publication of the Edward Splatt case in Flawed Forensics, David Szach approached me to examine and write up his case. I met with David Szach a number of times to record his version of events and his efforts to clear his name for the murder of lawyer Derrance Stevenson. After examining the trial transcripts, the grounds for appeal, and the reports by forensic scientists investigating the evidence presented by the forensic pathologist, I unravel the crime to reveal its hidden nature and consequences. CONTENTS Introduction … 1 1: Body in the freezer … 3 2: Prime suspect … 7 3: Derrance Stevenson and the Adelaide scene … 21 4: Before the trial … 26 5: Trial evidence … 32 6: Dr Colin Manock’s evidence … 47 7: David Szach’s statement … 60 8: Shaky underpinning for the Crown … 73 9: Blood and fingerprints -

Well Maintained Bores Last Longer

November 2015 Issue 75 ACROSS THE OUTBACK Montecollina Bore Well maintained bores last longer The SAAL NRM Board would like to remind water users in the 01 BOARD NEWS SA Arid Lands region who have a bore under their care and 01 Well maintained bores last longer control to undertake simple, routine maintenance to reduce 02 LEB partnership wins world’s highest river management honour risks to water supplies, prevent costly and inconvenient 04 LAND MANAGEMENT breakdowns, and to meet their legal obligations. 04 Innovative ‘Spatial Hub’ lands in The region’s largest water resource is the The review of 289 artesian bores in the Far South Australia Great Artesian Basin (GAB) which provides North Prescribed Wells Area was undertaken 05 Grader workshops help fight soil a vital supply of groundwater for the to establish a comprehensive picture of the erosion continued operation of our key industries condition of the artesian bores in South 06 Women’s Retreat hailed a success (tourism, pastoral, mining, gas and Australia. petroleum) and to meet the needs of our It highlighted that maintenance needs to 07 THREATENED SPECIES communities and wildlife. improve. 07 Are Ampurtas making a comeback? To safeguard the sustainability of the In recent decades, governments, industry 08 SA ARID LANDS – IT’S YOUR GAB and other groundwater aquifers the and individuals have invested significantly PLACE Far North Prescribed Wells Area Water in bore rehabilitation and installing piped Allocation Plan was adopted in 2009 after a reticulation systems to deliver GAB water 12 VOLUNTEERS planning process led by the Board under the efficiently. -

THE AUSTRALIAN GENUS GUNNIOPSIS PAX R. J. Chinnock

J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 6(2): 133-179 (1983) THE AUSTRALIAN GENUS GUNNIOPSIS PAX (AIZ OACEAE) R. J. Chinnock State Herbarium of South Australia, Botanic Gardens, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5000 Abstract Gunniopsis, which includes all Australian species previously included in Aizoon L. and Neogunnia Fax & Hoffm., is revised. Fourteen species are recognised and G. calcarea, G. calva, G. divisa, G. papillata, G. propin qua, G. rubra and G. tenuifolia are described as new. Two new combinations, G. kochii and G. septifraga are made. All species are illustrated and distribution maps and ecological data are provided. Gunniopsis is compared with Aizoon L. and Aizoanthemum Dinter ex Friedr., two African genera with which Gunniopsis has previously been compared or considered synonymous. Pollen, capsule and seed characters are discussed and illustrated. The majority of Gunniopsis species appear to be protandrous outcrossers, while a few are autogamous. Introduction The Australian species which have been previously referred to the genera Aizoon L., Gunniopsis Pax, Gunnia F. Muell. and Neogunnia Pax & Hoffmann are small succulent shrubs or herbs which are widespread throughout the eremaean zones of Western and South Australia with a few species extending into the adjacent portions of the Northern Territory, Queensland and New South Wales. With the exception of the shrubby Gunniopsis quadrifida which is very widespread and an important component of succulent shrublands in many areas, especially on saline soils in salt lake systems, most of the species have been poorly understood taxonomically. Doubt over the exact number of species found in Western Australia, for example, has resulted in considerable confusion. Gardner in his 1930 census listed six species under Gunniopsis and Gunnia, Blackall & Grieve (1954) included four under Gunniopsis and Gunnia while Green (1981) listed five under Aizoon, Gunniopsis and Neogunnia. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

NSW Repeaters.Xlsx

SA REPEATERS Channel 1 Callsign Location Status VLF7 Wirraminna Station Unconfirmed MUR01 Murreebirie Hill Online YAR01 Mt Yardea Unconfirmed VLE1 Elizabeth Downs Online GPR01 Glue Pot Unconfirmed ART01 Artracoona Hill Unconfirmed OLA01 Olary Online YAN01 Leigh Creek Unconfirmed CDA01 Coppudurba Hill Unconfirmed VLA5 Northside Hill Unconfirmed PRC01 Price Hill Unconfirmed MJN01 Mt Jane North Unconfirmed VLD8 Billa Kalina Station Unconfirmed VLC5 Mulgathing Rocks Unconfirmed VLF4 Rocky River Unconfirmed VLD5 Ulgera Gap Unconfirmed Channel 2 Callsign Location Status VHD7 Cordillo Unconfirmed DIN02 Arkaroola Unconfirmed MAT02 Wilpena Online MUN02 Mungerannie Online CAD02 Cadney Park Unconfirmed PAR02 Parcoola Station Unconfirmed VN002 Bond Hill Unconfirmed WIL02 William Creek Online COR02 Iron Knob Unconfirmed VLG6 Cockburn Unconfirmed VLC9 Loxton Online CLV02 Mt Nield Unconfirmed VLA4 Kingoonya Unconfirmed BRP02 Black Rock Unconfirmed VLB7 Mt Crispe Unconfirmed MYP02 Myponga Hill Unconfirmed BOR02 Bordertown Online MTS02 Mt Scott Online VLD6 Mobella Station Unconfirmed 1 Channel 3 Location Status VHU8 Mudlankie Hill Unconfirmed ELD03 Lake Elder Bore Unconfirmed WIL03 The Pinnacle Unconfirmed REN03 Renmark Unconfirmed MOO03 Mooleulooloo Unconfirmed BLN03 Patawarta Hill Unconfirmed UNO03 Yarna Station Unconfirmed CTR03 Bald Hill Unconfirmed ADL03 Glenelg North Unconfirmed KBY03 Kerby Hill Unconfirmed ALN03 Alindee Hill Unconfirmed VLD9 Bulgunnia Homestead Unconfirmed VLE3 Glendambo Unconfirmed VLE8 Murnpeowie Station Unconfirmed VLE9 Stenhouse -

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys Australis 2012

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis 2012 - 1 - This plan should be cited as follows: Moseby, K. (2012) National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Published by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Adopted under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: [date to be supplied] ISBN : 978-0-9806503-1-0 © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Government of South Australia. Requests and inquiries regarding reproduction should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Note: This recovery plan sets out the actions necessary to stop the decline of, and support the recovery of, the listed threatened species or ecological community. The Australian Government is committed to acting in accordance with the plan and to implementing the plan as it applies to Commonwealth areas. The plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a broad range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Queensland disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. -

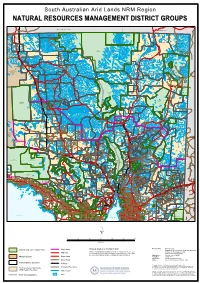

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella