Body Freezer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts & Culture Plan South Australia 2019

Arts & Culture Plan South Australia 2019 - 2024 1 To Dream To Explore To Create Acknowledgment of Country Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have made and continue to make a unique and irreplaceable contribution to Australia. The South Australian Government acknowledges and respects Aboriginal people as the state’s first people and nations, and recognises Aboriginal people as traditional owners and occupants of South Australian land and waters. The South Australian Government acknowledges that the spiritual, social, cultural and economic practices of Aboriginal people come from their traditional lands and waters, and that Aboriginal people maintain cultural and heritage beliefs, languages and laws which are of ongoing importance today. Front cover Production: mi:wi Organisation: Vitalstatistix Photographer: Gregory Lorenzutti Table of Contents Page Vision, Mission, 4 Values 4 6 Goals 5 Message and commitment from the Government 7 Introduction 9 An Arts Plan for the future 10 Why now is the time for the Plan 10 Four reasons to pivot 11 South Australia. A history of creative and cultural innovation 12 1 The Structure of this Plan 16 South Australia, A gateway to the first and original story 17 Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters 18 Goal 1 20 Goal 2 24 Goal 3 28 Goal 4 32 Goal 5 36 Goal 6 40 Capturing value and impact 42 Footnotes 44 Adelaide College of the Arts Organisation: TAFE SA Photographer: Sam Roberts The Arts and Culture Plan for This Arts Plan is about igniting a This narrative is about how we TELL South Australia 2019 – 2024 new level of connectivity – between THESE STORIES, and relates strongly artists, organisations, institutions and to South Australia’s ‘market and brand’. -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Government Gazette

No. 80 3145 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 24 JUNE 1999 CONTENTS Page Page Accident Towing Roster Scheme Regulations 1984— Public Sector Management Act 1995—Notices..................................................................3215 Notice...............................................................................................................................3159 Real Property Act 1886—Notice.........................................................................................3217 Acts Assented To...................................................................................................................3146 REGULATIONS Appointments, Resignations, Etc...........................................................................................3156 Evidence Act 1929—(No. 120 of 1999).........................................................................3272 Corporations and District Councils—Notices.......................................................................3285 Explosives Act 1936—(No. 121 of 1999).......................................................................3273 Crown Lands Act 1929—Notices.........................................................................................3157 Criminal Law (Sentencing) Act 1988— Dairy Industry Act 1992—Notice........................................................................................3183 (No. 122 of 1999)..........................................................................................................3274 -

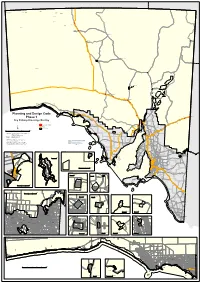

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Naretha Meteorite (Synonyms Kingoonya, Kingooya)

Rec. West. Aust. Mus., 1976, 4 (1) NARETHA METEORITE (Sync;>nyms: Kingoonya, Kingooya) W.H. CLEVERLY* [Received 27 May 1975. Accepted 1 October 1975. Published 31 August 1976.1 ABSTRACT Much of the missing portion of the Naretha (Western Australia) meteorite has been located in museums as an un-named specimen and as two smaller specimens masquerading under the name 'Kingoonya' (or 'Kingooya'). The use of the junior synonyms with their implications of a South Australian site of find should be discontinued. INTRODUCfION Naretha meteorite, an L4 chondrite, was found in 1915 about 3 km north of the 205-mile station during construction of the Trans-Australian Railway. It was broken into at least three major pieces which were acquired by Mr John Darbyshire, Supervising Engineer for the construction of the western end of the railway (construction was proceeding simultaneously from both Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta ends - Fig. 1). Mr Darbyshire donated the meteorite to the W.A. School of Mines in Kalgoorlie where one' piece was retained and exhibited with a photograph of the reassembled meteorite (Fig. 2). A second fragment which was passed on to the Geological Survey of Western Australia was noted briefly by Simpson (1922) who first used the name 'Naretha', the name which had been given to the 205-mile station. There is strong presumptive evidence that the third fragment was passed on to Mr S.F.C. Cook of Kalgoorlie, a private collector from whose inaccurate verbal statements and undocumented collection, the subsequent confusion arose. In late 1926 Mr Cook gave a small piece of 'meteorite to Mr G.W. -

Rear Admiral the Honourable Kevin Scarce AC CSC RAN (Rtd) Royal

Rear Admiral the Honourable Kevin Scarce AC CSC RAN (Rtd) Royal Commissioner Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission GPO Box 11043 Adelaide SA 5001 3 August 2015 Dear Sir, This is my consolidated submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission addressing selected questions from all Issues Papers. Issues Paper One: Exploration, Extraction and Milling My response to Question 1.7 regarding the demand for uranium in the medium and long term is as follows. To begin, I quote the Commissioner from the article titled, “Jobs in nuclear industry are ‘decades away’”, published in The Advertiser on 25 July 2015: “If we decided – and we haven’t decided yet – to recommend parts of the nuclear fuel cycle, it would be a couple of decades before we started to see the major impact.” I submit that at this point in time there is no way to prove a sound basis exists for concluding there will be increased demand for uranium in the medium and long term. No doubt nuclear proponents will point to the world’s increasing energy needs, especially of the two developing giants, China and India. On the demand side, it is true the world will be looking for emissions-free energy on a massive scale to replace traditional fossil fuels. If uranium for producing nuclear energy was the only option to replace fossil fuels, I would not be writing this submission. The fact is, it is not the only option. Another, better option exists in renewable energy, and I submit that in a much shorter time than it would take to establish a nuclear industry in South Australia, the world will be turning to renewables in force while eschewing nuclear energy. -

Citizens' Jury

SUNDAY VERSION South Australia’s Citizens’ Jury on Nuclear Waste Final Report November 2016 “Under what circumstances, if any, could South Australia pursue the opportunity to store and dispose of nuclear waste from other countries?” Jury Summary Statement The Citizens Jury would like to Acknowledge that we have been meeting on Kaurna land and we pay our respects to the Traditional owners, past and present, across South Australia. The jury generally had a strong conviction in taking a position one way or another. Two thirds of the jury do not wish to pursue the opportunity under any circumstances and one third support a commitment to pursue under the circumstances outlined in this report. Introduction: Citizen’s Jury 2 (CJ2) was a group of 350 residents of South Australia who were brought together under the remit of discussing and reporting on the question: “Under what circumstances, if any, could South Australia pursue the opportunity to store and dispose of high level nuclear waste from other countries?”. To be clear, the jury considered only high-level nuclear waste. The people on Citizen’s Jury Two were selected to be broadly representative of the population of South Australia based on demographics (as best as was possible based on the responses to the initial invitation to take part). The 50 jurors from Citizen’s Jury One were also invited back to be part of the second jury process and approximately 30 of them decided to take part in the second jury. On the first day of the jury, we established some guiding principles for how we should approach the process. -

Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre Peterborough

ENGINEERING HERITAGE RECOGNITION STEAMTOWN HERITAGE RAIL CENTRE PETERBOROUGH Engineering Heritage SA August 2017 Cover photograph: T Class Locomotive 199 was built by James Martin & Co of Gawler and entered service on 4 March 1912 It was taken out of service in 1970; displayed in a public park from 1973 to 1980; then stored in the roundhouse until 2008 when it was given a “cosmetic restoration” and placed on display in the former diesel depot [Photo: Richard Venus 4244] Table of Contents 1. Nomination for Engineering Heritage Recognition 1 2. Agreement of Owner 2 3. Description of Work 3 4. Assessment of Significance 5 5. Petersburg: Narrow Gauge Junction (1880-1919) 6 5.1 The “Yongala” Junction 6 5.2 Petersburg-Silverton 10 5.3 Silverton Tramway Company 14 5.4 Northern Division, South Australian Railways 16 5.5 Workshop Facilities 17 5.6 Crossing the Tracks 18 5.7 New Lines and the Break of Gauge 20 6. Peterborough: Divisional Headquarters (1918-1976) 23 6.1 Railway Roundhouse 23 6.2 The Coal Gantry 24 6.3 Rail Standardisation 29 7. Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre (1977- ) 31 7.1 Railway Preservation Society, 1977-2005 31 7.2 Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre (2005- ) 33 7.3 The Sound and Light Show 34 8. Associations 37 8.1 Railway Commissioners 37 8.2 Railway Contractors 38 9. Interpretation Plan 41 9.1 Interpretation 41 9.2 Marker Placement and Presentation Ceremony 41 Appendices A1. Presentation Ceremony 42 A1.1 Presentation of Marker 42 A1.2 Significance to Peterborough 46 A2. Steamtown Structures 47 A3. -

Public Transport Buildings of Metropolitan Adelaide

AÚ¡ University of Adelaide t4 É .8.'ìt T PUBLIC TRANSPORT BUILDII\GS OF METROPOLTTAN ADELAIDE 1839 - 1990 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning in candidacy for the degree of Master of Architectural Studies by ANDREW KELT (û, r're ¡-\ ., r ¡ r .\ ¡r , i,,' i \ September 1990 ERRATA p.vl Ljne2}oBSERVATIONshouldreadOBSERVATIONS 8 should read Moxham p. 43 footnote Morham facilities p.75 line 2 should read line 19 should read available Labor p.B0 line 7 I-abour should read p. r28 line 8 Omit it read p.134 Iine 9 PerematorilY should PerernPtorilY should read droP p, 158 line L2 group read woulC p.230 line L wold should PROLOGUE SESQUICENTENARY OF PUBLIC TRANSPORT The one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of public transport in South Australia occurred in early 1989, during the research for this thesis. The event passed unnoticed amongst the plethora of more noteworthy public occasions. Chapter 2 of this thesis records that a certain Mr. Sp"y, with his daily vanload of passengers and goods, started the first regular service operating between the City and Port Adelaide. The writer accords full credit to this unsung progenitor of the chain of events portrayed in the following pages, whose humble horse drawn char ò bancs set out on its inaugural joumey, in all probability on 28 January L839. lll ACKNO\ryLEDGMENTS I would like to record my grateful thanks to those who have given me assistance in gathering information for this thesis, and also those who have commented on specific items in the text. -

Zoos SA Annual Report 2011-12

zoossa.com.au zoossa.com.au Passion We inspire and influence through our valuable conservation efforts and recognise success. Effectiveness We focus on clearly defined shared goals and support people to achieve them. Innovation We seek creative ways to achieve goals and promote a culture of learning and improving. Integrity We are guided by our values and deliver on our promises. Respect We respect individual’s values and encourage a culture of collaboration, listening and trust. President’s Report .......................................2 CEO’s Report ............................................4 Board Members ...........................................6 List of Achievements ...................................7 The Animals ...........................................11 Conservation ............................................20 Education ................................................23 Sustainability ...........................................24 Visitation .................................................26 Communications & Development .................28 Our People ..............................................34 Assets & Infrastructure ..............................41 Life Members ...........................................42 Finance ...................................................54 AGM Minutes (2011) ................................59 SGM Minutes (2012) .................................62 Zoos South Australia Annual Report 2011/12 1 President’s Report Dusky Langur here is no question that the the overall direction of the business. -

Liquor Licensing Act 1997— Geographical Names Act 1991— (No

No. 81 5191 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 19 NOVEMBER 2009 CONTENTS Page Page Acts Assented To..................................................................... 5192 Mining Act 1971—Notices ..................................................... 5203 Appointments, Resignations, Etc............................................. 5192 National Parks and Wildlife (National Parks) Regulations Controlled Substances Act 1984—Notice ............................... 5193 2001—Notice....................................................................... 5204 Corporations and District Councils—Notices.......................... 5226 Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000—Notices .......... 5204 Crown Lands Act 1929—Notice ............................................. 5193 Proclamations .......................................................................... 5214 Development Act 1993—Notice ............................................. 5194 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................. 5244 Electoral Act 1985—Notice .................................................... 5194 Environment Protection Act 1993—Notices ........................... 5196 REGULATIONS Gas Act 1997—Notice ............................................................ 5194 Liquor Licensing Act 1997— Geographical Names Act 1991— (No. 267 of 2009)............................................................ -

Water Supply and Governance Options for Outback Towns in South Australia

Water Supply and Governance Options for Outback Towns in South Australia Eileen Willis, Meryl Pearce, Bradley Jorgensen and John Martin Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 15/7 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839-2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science-based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08-8303 8952 e-mail: [email protected] Citation Willis E. M., Pearce M. W., Jorgensen B. S., and Martin J. F., 2015, Water supply and governance options for outback towns in remote South Australia, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 15/7, Adelaide, South Australia Copyright © 2015 Flinders University To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of Flinders University. Disclaimer The participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research and does not warrant or represent the completeness of any information or material in this publication.