Mainstream Fields Are Structured by Power-Relations, with Strategies And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER TWO: Maghrebi Culture and Its Features 2.1 Introduction…………..…………………………………………………………...27

People’s Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Ministry of High Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Section of English Impact of Globalization on Maghrebi Culture Thesis submitted in candidacy for the degree of Master in English Literature and Civilization Presented by: Supervised by : Mr. Qwider LARBI Dr. Faiza SENOUCI- MBERBECH Mr. Noureddine BOUMEDIENE Academic year 2015-2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The greatest praise and thanks go, first of all, to ALLAH for helping and guiding us to the fulfilment of this work and achievement of our goals. We would like also to express our gratitude to our supervisor Dr. Faiza SENOUCI- MEBARBECH for her patience and advice throughout the preparation of this extended essay without her this work could not brought out into light. Special thanks go to Dr. Bensafa for his help and support. We are also grateful to all those who supported us with wise advice, insightful comments and valuable information at various stages of this work. At Last but not least, we owe our sincere and immense gratitude to all teachers of the English Department for their help and support throughout our academic career. II Dedications Thanks, first of All, to Allah Almighty Who enabled me to reach my goals. I also revere the patronage and moral support extended with love by my parents, brothers, sisters as well as all my extended family members whose support and encouragement made it possible for me to complete this dissertation. I submit my heartiest gratitude to my estimable teacher then supervisor Dr. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

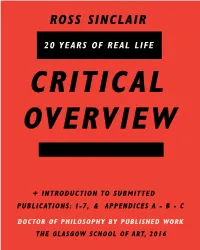

1- Critical-Overview.Pdf

Ross Sinclair 20 Years of Real Life Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work at The Glasgow School of Art, 2016 O Critical Overview Ross Sinclair Critical Overview, Introduction to Publications, Introduction to Appendices, Bibliography Ross Sinclair CRITICAL OVERVIEW Doctor of Philosophy by Published work The Glasgow School of Art 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work at The Glasgow School of Art. Ross Sinclair: 20 Years of Real Life Through a series of monograph publications, and other outputs, this submission examines the practice-led project: Real Life which I have developed through a series of interrelated artworks since 1994, beginning when I had the words REAL LIFE tattooed on my back. Declaration I declare that, except where explicit reference is made to the contribution of others, that this submission is the result of my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree at The Glasgow School of Art, University of Glasgow or any other institution. Signature Ross A. Sinclair Printed Name Ross A. Sinclair Abstract Abstract The submission, Ross Sinclair: 20 Years of Real Life consists of seven publications discussed in a critical overview, with three supporting Appendices. Together they document and analyse the diverse outputs of my practice-led research project, Real Life, initiated in 1994. The critical overview argues for the innovative nature of the Real Life Project through its engagement with audiences and demonstrates its contribution to the field of contemporary art practice, across the disciplines of sculpture, painting, performance, installation, critical writing and music. Drawing on multi-disciplinary methodologies, I reflect on the forms, materials and processes explored over 20 years of the Real Life Project, where everyday materials are utilised in unorthodox ways developing a series of installations and performances that seek to challenge conventional modes of exhibition practice. -

Military Tattoo Solo Travellers, 20 Day Package

Military Tattoo Solo Travellers 20 ay Package for 11-d August 2019 Britain and Ireland Panorama touring with Trafalgar and flying in economy class with a full service airline. From the spires of London, Edinburgh and York to wild, windswept landscapes of the Scottish Highlands and Ireland, explore all the nooks and crannies of Britain and Ireland - their historic cities, cultural diversity and breathtaking countryside on display as you explore such highlights as Dublin and Cardiff, and enjoy Highland cow company with Farmer John in Cumbria. Special Highlight – The Royal Military Tattoo while in Edinburgh. Flight Details Depart Brisbane 11 August to arrive in London 12 August 2019. Details to be advised YOUR CHALLENGE IF YOU WISH TO ACCEPT IT! Depart London 1 September to arrive in Brisbane 2 September 2019. The more people you get to go the cheaper it will be! Details to be advised Multi passenger discounts will kick in when more than 6 people have confirmed by a deposit payment so ask Package Inclusions: your friends and family to join in. The more the merrier and savings for everyone! Return economy class flights with a full service Airline to London (E.g Etihad, Singapore Airlines or Emirates). Terms and Conditions: Return airport to hotel transfers in London when not extending with own arrangements. All booking terms and conditions are as per Trafalgar Europe Brochure. Deposit and part payments are non- 3 nights pre-tour and 1 nights post tour stay in refundable. London. Flights cannot be transferred to another passenger at London city sightseeing tour on 13 August any time. -

April 2017 New Releases

April 2017 New Releases what’s featured exclusives PAGE inside 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 58 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 15 FEATURED RELEASES Music Video MICHAEL SCHENKER THE NIGHT EVELYN DONNIE DARKO LIMITED DVD & Blu-ray 45 - FEST: LIVE TOKYO CAME OUT OF THE... EDITION [BLU-RAY + DV... INTERNATIONAL FORU... Non-Music Video PAGE 57 PAGE 48 DVD & Blu-ray 49 PAGE 44 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 62 Order Form 66 Deletions and Price Changes 68 EMERSON, LAKE AND MARK MOTHERSBAUGH - ANN-MARGRET - SONGS 800.888.0486 PALMER - ONCE UPON... MUTANT FLORA FROM THE SWINGER AND... PAGE 6 PAGE 8 PAGE 63 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 EMERSON, LAKE AND PALMER - MARK MOTHERSBAUGH - ROGER MIRET www.MVDb2b.com ONCE UPON A TIME IN MUTANT FLORA AND THE DISASTERS - SOUTH AMERICA FADED Bad Eggs, Bunnymen and Peter Rottentail! This April, MVD lays some Easter goodies on you, and heading the pack is an ARROW VIDEO reissue of the cult classic DONNIE DARKO. Troubled high school student Donnie Darko has an imaginary friend-a six foot tall rabbit named Frank- that ‘helps’ him navigate through an increasingly bizarre life! Soundtrack features Duran Duran, Tears for Fears and (natch) Echo and the Bunnymen. DONNIE DARKO is hopped up with all the usual Arrow extra goodies, including interviews with stars Patrick Swayze and Drew Barrymore! Fill your baskets with caskets! An April shower of horror abounds with ABANDONED DEAD from Wild Eye Releasing. Torment and paranormal terrors will make you a basket case! And another Arrow Video gem, THE NIGHT EVELYN CAME OUT OF THE GRAVE graces our April schedule. -

Grand Tour of Britain & Ireland

GRAND TOUR OF BRITAIN & IRELAND 18 Day London to London May 12th - May 30th 2023 ITINERARY Day 1 ARRIVE IN LONDON, ENGLAND Day 2 LONDON (B) Day 3 LONDON–STONEHENGE – WIDECOMBE – PLYMOUTH (B) (D) Day 4 PLYMOUTH–GLASTONBURY–BATH–CARDIFF, WALES (B) Day 5 CARDIFF–TENBY–TRAMORE, IRELAND (B) Day 6 TRAMORE–BLARNEY–KILLARNEY (B) Day 7 KILLARNEY. RING OF KERRY EXCURSION (B) Day 8 KILLARNEY–DINGLE PENINSULA–ADARE–LIMERICK (B) Day 9 LIMERICK–CLIFFS OF MOHER–GALWAY–DUBLIN (B) Day 10 DUBLIN (B) Day 11 DUBLIN–CAERNARVON, WALES–LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND (B) Day 12 LIVERPOOL–LAKE DISTRICT–GRETNA GREEN, SCOTLAND – GLASGOW (B) (D) Day 13 GLASGOW–FORT WILLIAM–INVERNESS–CULLODEN MOOR–HIGHLANDS (B) (D) Day 14 HIGHLANDS–PITLOCHRY–ST. ANDREWS–EDINBURGH (B) Day 15 EDINBURGH (B) Day 16 EDINBURGH–JEDBURGH–YORK, ENGLAND–LEEDS (B) (D) Da7 17 LEEDS–STRATFORD-UPON-AVON–LONDON (B) Day 18 LONDON - Your vacation ends with breakfast this morning. (B) ACCOMMODATIONS Hotels subject to change INCLUDED FEATURES LONDON Novotel London West (F) R/T Motor Coach Shermans Dale to Airport PLYMOUTH Jury Inn (F) Round Trip Airfare CARDIFF Mercure (F) 18 Day Escorted Tour TRAMORE Majestic (ST) 17 Nights Hotel KILLARNEY Killarney Court (F) All Gov’t Taxes & Fees LIMERICK Limerick City Hotel (ST) 18 Full English breakfasts DUBLIN Bonnington (F) 5 three-course dinners with choice of menus LIVERPOOL Holiday Inn Liverpool City Centre (F) Pre Trip Meet & Greet GLASGOW Leoardo Inn West End (F) HIGHLANDS Carrbridge (F) Per person EDINBURGH Novotel Edinburgh Park (F) $4,799* double occupancy LEEDS Holiday Inn (F) LONDON Kensington Close (ST) or Novotel London West (F) JC Smith Travel 5263 Spring Rd *ALL PRICING AND INCLUDED FEATURES ARE BASED ON A MINIMUM OF Shermans Dale 20 PASSENGERS. -

Faouda Wa Ruina: a History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Trott, Brian Kenneth, "Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1934. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1934 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of a Degree of Master of Arts In History at The University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Gregory Carter While the punk rock and heavy metal subcultures have spread through much of the world since the 1980s, a heavy metal scene did not take shape in Morocco until the mid-1990s. There had yet to be a punk rock band there until the mid-2000s. In the following paper, I detail the rise of heavy metal in Morocco. Beginning with the early metal scene, I trace through critical moments in its growth, building up to the origins of the Moroccan punk scene and the state of those subcultures in recent years. -

A Five Capitals Investigation Into Festival Impacts

Richard Fletcher A five capitals investigation into festival impacts Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Science by Research De Montfort University Date of submission: January 2013 Minor revisions completed: June 2013 Sponsored by the Institute of Energy and Sustainable Development ABSTRACT The impact of festivals on contemporary society has proven, through ongoing investigation, to constitute a wide-ranging and highly contrasting set of costs and benefits. The Five Capitals model (Porritt, 2005) presents a comprehensive framework to guide the sustainable development of all products and services, that will be of particular interest when applied to the great variety of festivals, and their associated impacts. A framework will be developed, through which festivals can consider the range of impacts they have on natural, human, social, manufactured and financial sources of capital. The research approach of various festival organisations and of individuals working around festivals is considered throughout, how is knowledge gathered, what do ordering structures create, and what structures are created by this? The framework is applied in as much detail as possible to one festival, demonstrating a practical outcome, discussing the overall value of an integrated approach to reporting and finally suggesting future approaches. This research touches on wider contemporary issues, such as the practical workings of multi or inter-culturalist policies, costs/benefits of mega-events (such as the Olympics, -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Moreno Almeida, Cristina (2015) Critical reflections on rap music in contemporary Morocco : urban youth culture between and beyond state's co-optation and dissent. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20360 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Critical Reflections on Rap Music in Contemporary Morocco: Urban Youth Culture Between and Beyond State's Co-optation and Dissent Cristina Moreno Almeida Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2014 Centre for Cultural, Literary and Postcolonial Studies (CCLPS) SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Artist Song Title Disc # Artist Song Title Disc # (children's Songs) I've Been Working On The 04786 (christmas) Pointer Santa Claus Is Coming To 08087 Railroad Sisters, The Town London Bridge Is Falling 05793 (christmas) Presley, Blue Christmas 01032 Down Elvis Mary Had A Little Lamb 06220 (christmas) Reggae Man O Christmas Tree (o 11928 Polly Wolly Doodle 07454 Tannenbaum) (christmas) Sia Everyday Is Christmas 11784 She'll Be Comin' Round The 08344 Mountain (christmas) Strait, Christmas Cookies 11754 Skip To My Lou 08545 George (duet) 50 Cent & Nate 21 Questions 00036 This Old Man 09599 Dogg Three Blind Mice 09631 (duet) Adams, Bryan & When You're Gone 10534 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 09938 Melanie C. (christian) Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 09228 (duet) Adams, Bryan & All For Love 00228 (christmas) Deck The Halls 02052 Sting & Rod Stewart (duet) Alex & Sierra Scarecrow 08155 Greensleeves 03464 (duet) All Star Tribute What's Goin' On 10428 I Saw Mommy Kissing 04438 Santa Claus (duet) Anka, Paul & Pennies From Heaven 07334 Jingle Bells 05154 Michael Buble (duet) Aqua Barbie Girl 00727 Joy To The World 05169 (duet) Atlantic Starr Always 00342 Little Drummer Boy 05711 I'll Remember You 04667 Rudolph The Red-nosed 07990 Reindeer Secret Lovers 08191 Santa Claus Is Coming To 08088 (duet) Balvin, J. & Safari 08057 Town Pharrell Williams & Bia Sleigh Ride 08564 & Sky Twelve Days Of Christmas, 09934 (duet) Barenaked Ladies If I Had $1,000,000 04597 The (duet) Base, Rob & D.j. It Takes Two 05028 We Wish You A Merry 10324 E-z Rock Christmas (duet) Beyonce & Freedom 03007 (christmas) (duets) Year Snow Miser Song 11989 Kendrick Lamar Without A Santa Claus (duet) Beyonce & Luther Closer I Get To You, The 01633 (christmas) (musical) We Need A Little Christmas 10314 Vandross Mame (duet) Black, Clint & Bad Goodbye, A 00674 (christmas) Andrew Christmas Island 11755 Wynonna Sisters, The (duet) Blige, Mary J. -

AND the HEART Billboard 1

,tyt****ytyt*tt***ytyr***ytyt*******yt*ltytlryt**ytir******ytytr**yF***1ryt*yF**lryt*ytyt,tytyt**yttityt*yt MYSPACE MUSIC: THE FALLOUT //EARLY LOOK: SMART TV APPS * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * LLOYD II DOLLY PARTON II BIG SEAN //HANDSOME FURS * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Q UEE NS R CHE HANGS TOUGH // MICK MANAGEMENT'S M CD ONA LD ON MAYER ****************************************** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** JULY 9, 2011 www.billboard.com SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE www.billboard.biz 15 RISING STA RS: TECH N9NE * GIVERS * KENNETH WHALUM * FITZ AND THE TANTRUMS * INTOCABLE * PRETTY LIGHTS * COREY SMITH * ARCH ENEMY * STEPHEN COLBERT * & MORE GG It's unpretentieu , unrefined. Itfeels real. -SUB POP'S PON EM AN HOW COLLEGE RADIO, BLOGGERS, A BIDDING WAR AND A LOST PHONE BROUGHT TOGETHER SUB POP AND THE SLOW - BURNING, RED HOT THE HEAD AND THE HEART Billboard 1 ON THE CHARTS coNTI-NT,VOLUME 123, NO. 24 0 ALBUMS PAGE ARTIST /TITLE 42 JILL SCOTT / THE BILLBOARD 200 THE LIGHT OF THE SUN COREY SMITH / HEATSEEKERS 45 BROKEN RECORD 49 JUSTIN MOO ME / TOP COUNTRY OUTLAWS LIKE ME ALISON KRAUSS + UNION STATION I BLUEGRASS 49 PAPER AIRPLANE JILLUGHTOF TOP R &B /HIP -HOP THE LJGHT OF THE SUN AUGUST BURNS RED / CHRISTIAN LEVELER KIRK FRANKLIN / GOSPEL HELLO FEAR DANCE GAGA Y /ELECTRONIC BORN THISS WAY MICHAEL BUGLE / TRADITIONAL JAZZ 53 CRAZY LOVE CONTEMPORARY GABRIL BELLO I JAZZ 53 GABRIE BELLO MORMON TABERNACLECHOIR / TRADITIONAL CLASSICAL 53 UPFRONT THIS IS THE CHRIST DREAM / CLASSICAL CROSSOVER 53 5 THREE STRIKES IS OUT 9 6 Questions: Alison Haislip DREAM WITH ME 8 VARIOUS ARTISTS / Growing bandwidth usage Digital Entertainment WORLD 53 PLAYING FOR CHANGE: PFC2 is nudging ISPs to embrace 10 On The Road CAMELA / TOP LATIN 54 UN NUEVO DIA anti -P2P measures. -

KT 17-5-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, MAY 17, 2017 SHABAN 21, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net KD 117m spent North Korea Turkey brings Olynyk shines as on power plant link emerges back Ottoman Celtics down maintenance in global sports to revive Wizards to set up for summer5 cyber attacks7 past38 glory Cavs20 showdown Trump to give speech on Min 27º Max 44º Islam during Saudi visit High Tide 04:44 & 14:46 Low Tide US president defends revealing intel secrets to Russians 09:33 & 22:25 40 PAGES NO: 17230 150 FILS WASHINGTON: US President Donald Trump will urge unity between the world’s major faiths on an ambitious Kuwait backs first foreign trip that will take him to Saudi Arabia, the Vatican and Jerusalem, the White House said yesterday. call to extend National Security Advisor HR McMaster laid out a detailed itinerary for the “historic trip”, due to start late this week, and confirmed that Trump would address a oil output cuts gathering of Muslim leaders on his “hopes for a peaceful vision of Islam”. KUWAIT: Kuwait yesterday backed a call by top oil Previous US leaders have generally chosen a US producers Saudi Arabia and Russia to extend a deal neighbor such as Canada or Mexico for their first presi- on crude production cuts for nine more months. dential voyage, but Trump intends to plunge right into “Kuwait gives its full backing and support to the some of the world’s most difficult spiritual and political joint position of Saudi Arabia and Russia to extend conflicts. In Saudi Arabia, after a day of talks with King the oil output cuts deal between OPEC and other Salman and his crown prince, Trump will attend a gath- producers until March 2018,” Oil Minister Essam Al- ering of dozens of leaders from across the Muslim world.