It Is Relatively Stress-Free to Write About Computer Games As Nothing Too

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theescapist 042.Pdf

putting an interview with the Garriott Games Lost My Emotion” the “Gaming at Keep up the good work. brothers, an article from newcomer Nick the Margins” series and even “The Play Bousfield about an old adventure game, Is the Thing,” you described the need for A loyal reader, Originally, this week’s issue was The Last Express and an article from games that show the consequences of Nathan Jeles supposed to be “Gaming’s Young Turks Greg Costikyan sharing the roots of our actions, and allow us to make and Slavs,” an issue about the rise of games, all in the same issue. I’ll look decisions that will affect the outcome of To the Editor: First, let’s get the usual gaming in Eastern Europe, both in forward to your comments on The Lounge. the game. In our society there are fewer pleasantries dispensed with. I love the development and in playerbase. I and fewer people willing to take magazine, read it every week, enjoy received several article pitches on the Cheers, responsibility for their actions or believe thinking about the issues it throws up, topic and the issue was nearly full. And that their actions have no consequences. and love that other people think games then flu season hit. And then allergies Many of these people are in the marketing are more than they may first appear. hit. All but one of my writers for this issue demographic for video games. It is great has fallen prey to flu, allergies or a minor to see a group of people who are interested There’s one game, one, that has made bout of forgetfulness. -

Engaging with Videogames

INTER - DISCIPLINARY PRESS Engaging with Videogames Critical Issues Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Lisa Howard Dr Ken Monteith Advisory Board Karl Spracklen Simon Bacon Katarzyna Bronk Stephen Morris Jo Chipperfield John Parry Ann-Marie Cook Ana Borlescu Peter Mario Kreuter Peter Twohig S Ram Vemuri Kenneth Wilson John Hochheimer A Critical Issues research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/critical-issues/ The Cyber Hub ‘Videogame Cultures and the Future of Interactive Entertainment’ 2014 Engaging with Videogames: Play, Theory and Practice Edited by Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2014 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-295-9 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2014. First Edition. Table of Contents Introduction ix Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Part 1 Gaming Practices and Education Toward a Social-Constructivist View of Serious Games: Practical Implications for the Design of a Sexual Health Education Video Game 3 Sara Mathieu-C. -

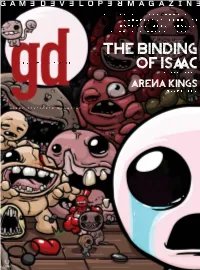

Game Developer Power 50 the Binding November 2012 of Isaac

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO 11 NOVEMBER 2012 INSIDE: GAME DEVELOPER POWER 50 THE BINDING NOVEMBER 2012 OF ISAAC www.unrealengine.com real Matinee extensively for Lost Planet 3. many inspirations from visionary directors Spark Unlimited Explores Sophos said these tools empower level de- such as Ridley Scott and John Carpenter. Lost Planet 3 with signers, artist, animators and sound design- Using UE3’s volumetric lighting capabilities ers to quickly prototype, iterate and polish of the engine, Spark was able to more effec- Unreal Engine 3 gameplay scenarios and cinematics. With tively create the moody atmosphere and light- multiple departments being comfortable with ing schemes to help create a sci-fi world that Capcom has enlisted Los Angeles developer Kismet and Matinee, engineers and design- shows as nicely as the reference it draws upon. Spark Unlimited to continue the adventures ers are no longer the bottleneck when it “Even though it takes place in the future, in the world of E.D.N. III. Lost Planet 3 is a comes to implementing assets, which fa- we defi nitely took a lot of inspiration from the prequel to the original game, offering fans of cilitates rapid development and leads to a Old West frontier,” said Sophos. “We also the franchise a very different experience in higher level of polish across the entire game. wanted a lived-in, retro-vibe, so high-tech the harsh, icy conditions of the unforgiving Sophos said the communication between hardware took a backseat to improvised planet. The game combines on-foot third-per- Spark and Epic has been great in its ongoing weapons and real-world fi rearms. -

A Clash Between Game and Narrative

¢¡¤£¦¥¦§¦¨©§ ¦ ¦¦¡¤¥¦ ¦¦ ¥¦§ ¦ ¦ ¨© ¦¡¤¥¦¦¦¦¡¤¨©¥ ¨©¦¡¤¨© ¦¥¦§¦¦¥¦ ¦¦¦ ¦¦¥¦¦¨©§¦ ¦!#" ¦$¦¥¦ %¤©¥¦¦¥¦©¨©¦§ &' ¦¦ () ¦§¦¡¤¨©¡*¦¡¤¥ ,+- ¦¦¨© ./¦ ¦ ¦¦¦¥ ¦ ¦ ./¨©¡¤¥ ¦¦¡¤ ¦¥¦0#1 ¦¨©¥¦¦§¦¨©¡¤ ,2 ¦¥¦ ¦£¦¦¦¥ ¦0#%¤¥¦$3¦¦¦¦46555 Introduction ThisistheEnglishtranslationofmymaster’sthesisoncomputergamesandinteractivefiction. Duringtranslation,Ihavetriedtoreproducemyoriginalthesisratherfaithfully.Thethesiswas completedinFebruary1999,andtodayImaynotcompletelyagreewithallconclusionsorpresup- positionsinthetext,butIthinkitcontinuestopresentaclearstandpointontherelationbetween gamesandnarratives. Version0.92. Copenhagen,April2001. JesperJuul Tableofcontents INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................... 1 THEORYONCOMPUTERGAMES ................................................................................................................................ 2 THEUTOPIAOFINTERACTIVEFICTION...................................................................................................................... 2 THECONFLICTBETWEENGAMEANDNARRATIVE ...................................................................................................... 3 INTERACTIVEFICTIONINPRACTICE........................................................................................................................... 4 THELUREOFTHEGAME.......................................................................................................................................... -

Download Resume

Objective A high performing, team-player in art direction, web design, and award winning computer animation, I am seeking a challenging full time opportunity to direct projects where my advanced skills, education, and 15+ years of professional experience can be fully utilized. Nicole Tostevin Summary of Qualifications Contact • Art Direction • Ecommerce Experience 415.203.0721 • Product Design • eLearning Educational Design [email protected] • Integrated Brand Design • Animatics • UI/UX Design • User Research Online Portfolio • Storyboarding • Usability Testing www.redheadart.com • WordPress Design/Development • User Stories / Journeys / Flows • Responsive Web Design • Interviews and Surveys • Information Graphics/Animation • Sketch |Wireframes • Social Media Design • Interactive Prototyping • Multimedia Storytelling • Low/High Fidelity Mockups • Graphic Design | Illustration • Style Guides • Animation | Motion Graphics • Mood Boards Education • CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF THE ARTS M.F.A. Experimental Animation, Graduate Film School, Valencia, CA • SAN FRANCISCO ART INSTITUTE 1/3 of M.F.A. work in Graduate Video, Computer Art, Performance Art • POMONA COLLEGE B.F.A. Art Major, Claremont Colleges, Claremont, CA Computer & Technology Skills • Adobe Creative Suite • Principle • Sketch | Zeplin • InVision • Adobe Experience Design • Framer • Adobe Photoshop • Keynote | PowerPoint • Adobe Illustrator • Google Slides • After Effects / Cinema 4D • Adobe Captivate • Premiere Pro • Docebo LMS • Adobe Animate • Google Web Designer • Flash | -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

Millennium Stories: Interactive Narratives and the New Realism

ch7.qxd 11/15/1999 9:13 AM Page 149 7 Millennium Stories: Interactive Narratives and the New Realism In contrast to our vast knowledge of how science and logical reasoning proceeds, we know precious little in any formal sense about how to make good stories. —Jerome Bruner, Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (1986) “[S]urrender . and the intimacy to be had in allowing a beloved author’s voice into the sanctums of our minds, are what the common reader craves,” writes Laura Miller.1 Sven Birkerts sounds a similar note of surrender in The Gutenberg Elegies: “This ‘domination by the author’ has been, at least until now, the point of writing and reading. The author masters the resources of language to create a vision that will engage and in some way overpower the reader; the reader goes to work to be subjected to the creative will of another.”2 As we saw in chapter 1, like many readers with a slender experience of the medium, both critics assume that, if interactive narratives do not spell the Death of the Author that Roland Barthes described in his famous essay of that name, interactivity will diminish the author’s role, make it nearly irrelevant—a fear, as we discovered with the intentional net- work, that is as lacking in substance as it is naive. Strikingly, both Miller and Birkerts assume they speak for the desires and predilections of the Reader, as if the New York Times best- seller list or most of the books toted home by shoppers at Barnes and Noble represent the Great Works of the century, the titles that ‹nd their way onto college curricula and not ephemera that frequently go out of print and are forgotten by the decade’s end. -

Finding Aid to the Jordan Mechner Papers, 1913-2016

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Jordan Mechner Papers Finding Aid to the Jordan Mechner Papers, 1913-2016 Summary Information Title: Jordan Mechner papers Creator: Jordan Mechner (primary) ID: 114.1911 Date: 1913–2016 (inclusive); 1984–1999 (bulk) Extent: 32 linear feet (physical); 922 GB (digital) Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English, though there are instances of French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Japanese. Abstract: The Jordan Mechner papers are a compilation of game design documentation, notes, reference materials, drawings, film, video, photographs, source code, business records, legal documents, correspondence, and marketing materials created and retained by Jordan Mechner during his career in the video game industry. The bulk of the materials are dated between 1984 and 1999. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Access: Some materials of financial or legal nature have been restricted by the donor. These documents will not be open for research use until the year 2044. They are denoted as such in this finding aid and are separated from unrestricted files. Conditions Governing Use: The remainder of this collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. -

Off-The-Shelf Narrative Games in History Classrooms

The Challenges of using Commercial- Off-the-Shelf Narrative Games in History Classrooms Richard Eberhardt Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Ave Bldg E15-329 617-324-2173 [email protected] Kyrie Eleison Caldwell Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] ABSTRACT As part of an Arthur Vining Davis-funded project conducted by the MIT Education Arcade, the author designed a lesson plan for a Lynn, MA teacher’s 9th grade World History class, focused on the beginning of her World War 1 unit. This plan utilized a commercial, off- the-shelf game, The Last Express (Mechner 1997), originally developed and published for entertainment purposes. The lesson plan was developed to test the feasibility of using story- based narrative games with historical elements as a prelude to a critical writing exercise. The test was to see how students reacted to the game, both as a gameplay exercise and as a source of content, and whether students would be able make logical connections between the game and their other non-game classwork. This paper outlines the research that went into designing this lesson plan and identifies challenges educators might face bringing these games into their classrooms. Keywords Secondary Education, World History, Narrative Games, Curriculum Design INTRODUCTION Since before the first commercially published wargames, particularly Tactics (Roberts 1953) and Tactics II (Roberts 1958), human history has been a rich vein for inspiration in entertainment game design and development, not just as depictions -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

Screw the Grue

the international journal of volume 7 issue 1 computer game research August 2007 ISSN:1604-7982 home about archive RSS Search Screw the Grue: Mediality, Metalepsis, Recapture Terry Harpold by Terry Harpold Terry Harpold is an Associate I begin with an assertion that I consider an axiom of videogame studies. Gameplay is Professor of English, Film and Media Studies at the the expression of combinations of definite semiotic elements in specific relations to University of Florida. His book equally definite technical elements. The semiotic plane of a game’s expression draws on Ex-Foliations: Reading Machines and the Upgrade the full range of common cultural material available to game designers and players: Path is forthcoming from shared myth, conventions of genre and narrative form, comprehension of the relevant University of Minnesota Press. intertextual canons, etc. The technical plane of the expression - computational, electronic and mechanical systems that support game play - is the more restricted. Its elements are localized to a given situation of play (this software, this hardware) in ways that the semiotic elements of play seem not to be (Where do relevant cultural myth and the intertextual canon start and stop? Will this not vary according to the competence of the player?) . Moreover, because the technical elements of play should demonstrate the consistency and stability fundamental to usable computing devices, they are deterministic and capable of only finitely many configurations. (For the present and the foreseeable future, we play in Turing’s world.) The challenge of game design is to program the entanglement of semiotic and technical elements in an interesting and rewarding way. -

IFN January 1998

“Interactive Fiction Now” Published for the World Wide Web by Frotz Publications Copyright 1997,1998, Frotz Publications, London. All rights reserved. http://www.if-now.demon.co.uk/ Editor: Matt Newsome, <[email protected]>. All Trademarks acknowledged. Blade Runner, The Film, © 1982 The Blade Runner Partnership Blade Runner, The Computer Game © 1997 Blade Runner / Westwood Partnership Blade Runner is a Trade Mark of the Blade Runner Partnership Tomb Raider II © and TM Core Design Limited, © and (P) 1997 Eidos Interactive Limited. All rights reserved. Activision and Zork are registered trademarks and Zork Grand Inquisitor and all character names and likenesses are trademarks of Activision, Inc. © 1997 Activision, Inc. All rights reserved. This issue of IFN owes a debt of gratitude to the following people (in alphabetical order): Sophie Astin at The Digital Village Simon Byron at Bastion Charles Cecil at Revolution Software Jamey Gottlieb at Activision Susie Hamilton at Core Design Laird Malamed at Activision Danny Pample at CUC Software Morag Pavich at Hobsbawm Macaulay Communications TIME marches on and Xmas has been and gone again! E Best wishes for a Happy New Year from IFN Magazine! D This issue of IFN is packed full of We’ve a sneak look at Douglas features for Adventure fans. Adams’ new game, Starship Titanic and Gabriel Knight 3 I Following our exclusive interview from Sierra. with the director of Zork: Grand Inquisitor last month, we review Our feature this issue, however, the latest journey into the Great is an exclusive interview with T Underground Empire. Charles Cecil, industry Grand- Daddy and cutting edge game The sequel to Tomb Raider also developer in equal measure.