Journal2012 Master 13-09-12 Journal2010 Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Landform Studies in Mosedale, Northeastern Lake District: Opportunities for Field Investigations

Field Studies, 10, (2002) 177 - 206 LANDFORM STUDIES IN MOSEDALE, NORTHEASTERN LAKE DISTRICT: OPPORTUNITIES FOR FIELD INVESTIGATIONS RICHARD CLARK Parcey House, Hartsop, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 0NZ AND PETER WILSON School of Environmental Studies, University of Ulster at Coleraine, Cromore Road, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Mosedale is part of the valley of the River Caldew in the Skiddaw upland of the northeastern Lake District. It possesses a diverse, interesting and problematic assemblage of landforms and is convenient to Blencathra Field Centre. The landforms result from glacial, periglacial, fluvial and hillslopes processes and, although some of them have been described previously, others have not. Landforms of one time and environment occur adjacent to those of another. The area is a valuable locality for the field teaching and evaluation of upland geomorphology. In this paper, something of the variety of landforms, materials and processes is outlined for each district in turn. That is followed by suggestions for further enquiry about landform development in time and place. Some questions are posed. These should not be thought of as being the only relevant ones that might be asked about the area: they are intended to help set enquiry off. Mosedale offers a challenge to students at all levels and its landforms demonstrate a complexity that is rarely presented in the textbooks. INTRODUCTION Upland areas attract research and teaching in both earth and life sciences. In part, that is for the pleasure in being there and, substantially, for relative freedom of access to such features as landforms, outcrops and habitats, especially in comparison with intensively occupied lowland areas. -

F. Fraser Darling Natural History in the Highlands and Islands

F. Fraser Darling Natural History in the Highlands and Islands Аннотация The Highlands and Islands of Scotland are rugged moorland, alpine mountains and jagged coast with remarkable natural history. This edition is exclusive to newnaturalists.comThe Highlands and Islands of Scotland are rugged moorland, alpine mountains and jagged coast with remarkable natural history, including relict and specialised animals and plants. Here are animals in really large numbers: St. Kilda with its sea-birds, North Rona its seals, Islay its wintering geese, rivers and lochs with their spawning salmon and trout, the ubiquitous midges! This is big country with red deer, wildcat, pine marten, badger, otter, fox, ermine, golden eagle, osprey, raven, peregrine, grey lag, divers, phalaropes, capercaillie and ptarmigan. Off-shore are killer whales and basking sharks. Here too in large scale interaction is forestry, sheep farming, sport, tourism and wild life conservation. Содержание Natural History in the Highlands and Islands 6 Editors: 8 Table of Contents 9 EDITORSâ PREFACE 11 AUTHORâS PREFACE 14 CHAPTER 1 16 CLIMATE 31 CHAPTER 2 48 THE SOUTHERN AND EASTERN 49 HIGHLAND FRINGE THE CENTRAL HIGHLAND ZONE 56 THE NORTHERN HIGHLANDS, A ZONE OF 62 SUB-ARCTIC AFFINITIES CHAPTER 3 74 THE WESTERN HIGHLANDS OR 75 ATLANTIC ZONE THE OUTER HEBRIDES OR OCEANIC 93 ZONE CHAPTER 4 108 Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. 132 Collins New Naturalist Library 6 Natural History in the Highlands and Islands F. Fraser Darling D.Sc. F.R.S.E. With 46 Colour Photographs By F. Fraser Darling, John Markham and Others, 55 Black-and-White Photographs and 24 Maps and Diagrams TO THE MEMORY OF WILLIAM ORR, F.R.C.V.S. -

List of Illustrations from Chapter 4, Natural History of Upper Weardale, Geomorphology and Glacial Legacy

List of Illustrations from Chapter 4, Natural History of Upper Weardale, Geomorphology and glacial legacy. by David J A Evans This document provides a larger version of the illustrations for Chapter 4 of the Natural History of Upper Weardale, Geomorphology and Glacial Legacy. By providing this in a PDF format it should be possible to enlarge to some extent and gain a clearer insight. Figure 1: Northern England contour colour coded digital elevation model (DEM) derived from NEXTMap imagery (courtesy of NERC via the Earth Observation Data Centre). The main physiographic areas are highlighted and include the streamlined (drumlin filled) corridors created by fast ice stream flow during glaciations. The fluvial drainage pattern and largely V-shaped valley cross profiles of the North Pennines (Alston Block) are also prominent. (a) (b) Figure 2: Previous reconstructions of the glaciation of the North Pennines: a) the valley-confined style of glaciation of the north Pennines produced by Dwerryhouse (1902). The Stainmore Gap and Tyne Gap ice streams drain the regional, Scottish-nourished ice eastwards and the North Pennines are characterized by the Teesdale, South Tyne and Weardale glaciers. Note the prominent ice-dammed lakes that are depicted along the south edge of Tyne Gap ice but also smaller examples along the margins of the Teesdale and Weardale glaciers; b) a similar depiction of the regional ice by Raistrick and Blackburn (1931), showing what they regarded as a later stage of ice sheet recession. Figure 3: Examples of the lithological -

Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report

_..._ Natural Environment Research Council -2 Institute of Geological Sciences - -- Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report c- - _.a - A report prepared for the Department of Industry -- This report relates to work carried out by the British Geological Survey.on behalf of the Department of Trade I-- and Industry. The information contained herein must not be published without reference to the Director, British Geological Survey. I- 0. Ostle Programme Manager British Geological Survey Keyworth ._ Nottingham NG12 5GG I No. 72 I A geochemical drainage survey of the Preseli Hills, south-west Dyfed, Wales I D I_ I BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Natural Environment Research Council I Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report No. 72 A geochemical drainage survey of the I Preseli Hills, south-west Dyfed, Wales Geochemistry I D. G. Cameron, BSc I D. C. Cooper, BSc, PhD Geology I P. M. Allen, BSc, PhD Mneralog y I H. W. Haslam, MA, PhD, MIMM $5 NERC copyright 1984 I London 1984 A report prepared for the Department of Trade and Industry Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Reports 58 Investigation of small intrusions in southern Scotland 31 Geophysical investigations in the 59 Stratabound arsenic and vein antimony Closehouse-Lunedale area mineralisation in Silurian greywackes at Glendinning, south Scotland 32 Investigations at Polyphant, near Launceston, Cornwall 60 Mineral investigations at Carrock Fell, Cumbria. Part 2 -Geochemical investigations 33 Mineral investigations at Carrock Fell, Cumbria. Part 1 -Geophysical survey 61 Mineral reconnaissance at the -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 2013

Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 2013 Lynne Farrell Jane Squirrell Graham French Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 Lynne Farrell, Jane Squirrell and Graham French © Lynne Farrell, BSBI VCR. 2013 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 2. VC 103 MAP ......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. EXTANT TAXA ...................................................................................................................................... 5 4. PLATES............................................................................................................................................... 10 5. RARE PLANT REGISTER ....................................................................................................................... 14 6. EXTINCT SPECIES .............................................................................................................................. 119 7. RECORDERS’ NAME AND INITIALS .................................................................................................... 120 8. REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................... 123 Cover image: Cephalanthera longifolia (Narrow-leaved Helleborine) [Photo Lynne Farrell] Mid Ebudes Rare Plant Register -

Newsieblack Combe Runners

NewsieBlack Combe Runners Summer 2011: the Bob issue Captain Pete’s Ramblings It’s great to see so many new faces at the club. We hovered around 50 Apologies if I have missed someone! Soon (I am often told) there will members for years but last year went over 60 and in 2011 we should have be a list of members on the website, and this will save me from having to well over 70 runners. remember. Some of those who joined us last year have instantly become core So here’s to a great season of fast running active members of the club – Jamie could only wait 15 months before Pete Tayler completing his Bob Graham Round and Helen went straight into the fell and road races. Jackie rejoined the club last year and achieved a placing in the English Championships, and is in line for another top 10 this year. A word from the new Ed Of this year’s new members, Richard Watson has put in some great races So I tied Will to the chair and set about doing a Newsie. I mean, how (he was 4th at Carnforth 20 barriers) and Tim Faudemer turned up hard can it be? I have the stories and I have the pictures, I’ll just knock on his first Tuesday night run to be met on Slight Side by Mike Vogler out a quick Newsie. First I have to learn how to use a Mac and a new in tuxedo serving him some bubbly. Mike has also instigated a regular program, but that should present me with no problems at all. -

TA 7.5 Figure 1 Key Achany Extension Wind Farm EIA

WLA 38: Ben Hope - Ben Loyal Northern Arm Key Site Boundary 40km Wider Study Area 20km Detailed Study Area 5 km Buffer WLA 37: Foinaven - Ben Hee !( Proposed Turbine !( Operational Turbine !( Consented Turbine Wild Land Area (WLA) 34: Reay - Cassley !( !( !( !( !( Other WLA !( !( !( !( !( !( !( WLA 33: Quinag !( !( Creag Riabhach WLA Sub-Section Divider !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !Z !( Assessment Location Access Route to Assessment WLA 35: Ben Klibreck Location Central Core - Armine Forest Map of Relative Wildness High 5 !Z Low 6 !Z 4 3 Map of relative wildness GIS information obtained !Z !Z from NatureScot Natural Spaces website: http://gateway.snh.gov.uk/natural-spaces/index.jsp WLA 32: Inverpolly - Glencanisp 7 !Z Eastern Lobster Claw !( !( !( 2 1 !( !( !Z !( !Z !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Western !( Lobster Claw !( !( Lairg Scale 1:175,000 @ A3 !( !( Km !( !( Achany !(!( !( 0 2 4 6 !( !( !( !( !( ± !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Braemore Lairg 2 !( TA 7.5 Figure 1 !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Map of Relative Wildness (WLA 34) !( !( WLA 29: Rhiddoroch - !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Beinn Dearg - Ben Wyvis !( !( Rosehall !( !( !( !( !( !( Achany Extension Wind Farm EIA Report Drawing No.: 120008-TA7.5.1-1.0.0 Date: 07/07/2021 © Crown copyright and database rights 2021 Ordnance Survey 0100031673 WLA 38: Ben Hope Northern Arm - Ben Loyal Site Boundary 40km Wider Study WLA 37: Foinaven 20km Detailed Study - Ben Hee 5 km Buffer !( Proposed Turbine Wild Land Area (WLA) 34: Reay - Cassley Other -

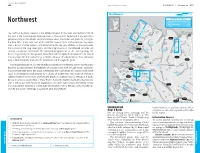

NORTHWEST © Lonelyplanetpublications Northwest Northwest 256 and Thedistinctive, Seeminglyinaccessiblepeakstacpollaidh

© Lonely Planet Publications 256 www.lonelyplanet.com NORTHWEST •• Information 257 0 10 km Northwest 0 6 miles Northwest – Maps Cape Wrath 1 Sandwood Bay & Cape Wrath p260 Northwest Faraid 2 Ben Loyal p263 Head 3 Eas a' Chùal Aluinn p266 H 4 Quinag p263 Durness C Sandwood Creag Bay S Riabach Keoldale t (485m) To Thurso The north of Scotland, beyond a line joining Ullapool in the west and Dornoch Firth in r Kyle of N a (20mi) t Durness h S the east, is the most sparsely populated part of the country. Sutherland is graced with a h i n Bettyhill I a r y 1 Blairmore A838 Hope of Tongue generous share of the wildest and most remote coast, mountains and glens. At first sight, Loch Eriboll M Kinlochbervie Tongue the bare ‘hills’, more rock than earth, and the maze of lochs and waterways may seem Loch Kyle B801 Cranstackie Hope alien – part of another planet – and unattractive. But the very wildness of the rockscapes, (801m) r Rudha Rhiconich e Ruadh An Caisteal v the isolation of the long, deep glens, and the magnificence of the indented coastline can E (765m) a A838 Foinaven n Laxford (911m) Ben Hope h Loch t exercise a seductive fascination. The outstanding significance of the area’s geology has Bridge (927m) H 2 Loyal a r been recognised by the designation of the North West Highlands Geopark (see the boxed t T Scourie S Loch Ben Stack Stack A836 text on p264 ), the first such reserve in Britain. Intrusive developments are few, and many (721m) long-established paths lead into the mountains and through the glens. -

37 Foinaven - Ben Hee Wild Land Area

Description of Wild Land Area – 2017 37 Foinaven - Ben Hee Wild Land Area 1 Description of Wild Land Area – 2017 Context This large Wild Land Area (WLA) extends 569 km2 across north west Sutherland, extending from the peatlands of Crask in the south east to the mountain of Foinaven in the north west. The northern half of the WLA mainly comprises a complex range of high mountains in addition to a peninsula of lower hills extending towards Durness. In contrast, the southern half of the WLA includes extensive peatlands and the isolated mountain of Ben Hee. One of a cluster of seven WLAs in the north west of Scotland, flanked by main (predominantly single track) roads to the north, west and south, it is relatively distant from large population centres. The geology of the area has a strong influence on its character. Along the Moine Thrust Belt that passes through the north west, rocky mountains such as Foinaven and Arkle are highly distinctive with their bright white Cambrian quartzite and scree, with little vegetation. The geological importance of this area is recognised by its inclusion within the North West Highlands Geoparki. Land within the WLA is used mainly for deer stalking and fishing and, except for a few isolated estate lodges and farms, is uninhabited. Many people view the area from outside its edge as a visual backdrop, particularly when travelling along the A838 between Lairg and Laxford Bridge and Durness, and along the A836 between Lairg and Altnaharra, through Strath More, and around Loch Eriboll. The mountains within this WLA typically draw fewer hillwalkers than some other areas, partly due to the lack of Munros. -

Blackcurrant Breeding and Research at the James Hutton Institute

Blackcurrant Breeding and Research at The James Hutton Institute Rex Brennan Fruit Breeding Group Blackcurrant Breeding at JHI Plan • Breeding programmes and cultivar releases to date Processing and fresh market • New techniques for selecting the plants we need Marker–assisted breeding strategies • Emerging challenges Environmental effects eg. reducing levels of winter chilling Can we improve on the cultivars we already have? Blackcurrant Cultivars Ben Avon Big Ben Ben Dorain Ben Gairn* Ben Vane Ben Finlay* Ben Klibreck Ben Maia Ben Starav + + Ben Como Ben Chaska Ben Hope * First commercial UK cv. with resistance to BRV * First commercial UK processing cv. with resistance to gall mite + First UK cvs released in USA Breeding Objectives Fruit quality Agronomic High Brix/acid ratio Environmental resilience Low total acidity Winter chill levels < 2000 h/7.2oC Anthocyanins Pest resistance for low-input Delphinidins preferentially selected growing Vitamin C (AsA) Acceptable crop yield > 140 mg/100 ml > 6 t/ha Sensory traits Juice yield also quantified Berry size 1g minimum Fresh Market Blackcurrants Increasing interest • Predominantly related to health benefits Different requirements and breeding objectives • Often different cultural practices •Hand harvesting •Grown on wires in some areas • Large berries preferred • 2g + • Green strigs preferred • Aiming for berries suitable for eating fresh •Higher Brix/acid ratios Big Ben Recent releases Ben Starav (Ben Alder x ([E29/1 x (93/20 x S100/7)] x [ND21/12 x 155/9]) Consistently