Nintendo Wii) to Increase Activity Levels, Vitality and Well-Being in People with Multiple Sclerosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wii-Workouts on Chronic Pain, Physical Capabilities and Mood of Older Women: a Randomized Controlled Double Blind Trial

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico do Porto Wii-Workouts on Chronic Pain, Physical Capabilities and Mood of Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Double Blind Trial Renato Sobral Monteiro-Junior; Cíntia Pereira de Souza; Eduardo Lattari; Nuno Barbosa Ferreira Rocha; Gioia Mura; Sérgio Machado; Elirez Bezerra da Silva Abstract Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP) is a public health problem and older women have higher incidence of this symptom, which affect body balance, functional capacity and behavior. The purpose of this study was to verifying the effect of exercises with Nintendo Wii on CLBP, functional capacity and mood of elderly. Thirty older women (68 ± 4 years; 68 ± 12 kg; 154 ± 5 cm) with CLBP participated in this study. Elderly individuals were divided into a Control Exercise Group (n = 14) and an Experimental Wii Group (n = 16). Control Exercise Group did strength exercises and core training, while Experimental Wii Group did ones additionally to exercises with Wii. CLBP, balance, functional capacity and mood were assessed pre and post training by the numeric pain scale, Wii Balance Board, sit to stand test and Profile of Mood States, respectively. Training lasted eight weeks and sessions were performed three times weekly. MANOVA 2 x 2 showed no interaction on pain, siting, stand-up and mood (P = 0.53). However, there was significant difference within groups (P = 0.0001). ANOVA 2 x 2 showed no interaction for each variable (P > 0.05). However, there were significant differences within groups in these variables (P < 0.05). -

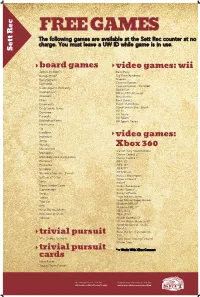

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Backyard Football Manual Interior Nintendo Wii Front

BACKYARD FOOTBALL MANUAL INTERIOR NINTENDO WII FRONT COVER PLACEHOLDER PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. WARNING – Seizures • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or patterns, and this may occur while they are watching TV or playing video games, even if they have Nintendo, Wii and the Official Seal are trademarks of Nintendo. © 2006 Nintendo. never had a seizure before. Licensed by Nintendo • Anyone who has had a seizure, loss of awareness, or other symptom linked to an epileptic condition, should consult a doctor before playing a video game. • Parents should watch their children play video games. Stop playing and consult a doctor if you or your child has any of the following symptoms: Convulsions Eye or muscle twitching Altered vision CONTENTS Loss of awareness Involuntary movements Disorientation • To reduce the likelihood of a seizure when playing video games: Controls.................................................................................... 2 1. Sit or stand as far from the screen as possible. Gestures................................................................................... 4 2. Play video games on the smallest available television screen. 3. Do not play if you are tired or need sleep. Saving.and.Loading.................................................................. 5 4. Play in a well-lit room. 5. -

Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components in Institutionalized Older Adults Jerónimo J. González-Bernal 1 , Maha Jahouh 1,* , Josefa González-Santos 1,*, Juan Mielgo-Ayuso 1,* , Diego Fernández-Lázaro 2,3 and Raúl Soto-Cámara 1 1 Department of Health Sciences, University of Burgos, 09001 Burgos, Spain; [email protected] (J.J.G.-B.); [email protected] (R.S.-C.) 2 Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Campus of Soria, University of Valladolid, 42003 Soria, Spain; [email protected] 3 Neurobiology Research Group, Faculty of Medicine, University of Valladolid, 47005 Valladolid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (J.G.-S.); [email protected] (J.M.-A.) Abstract: Aging is a multifactorial physiological phenomenon in which cellular and molecular changes occur. These changes lead to poor locomotion, poor balance, and an increased falling risk. This study aimed to determine the impact and effectiveness of the use of the Wii® game console on improving walking speed and balance, as well as its influence on frailty levels and falling risk, in older adults. A longitudinal study was designed with a pretest/post-test structure. The study population comprised people over 75 years of age who lived in a nursing home or attended a day care center (n = 80; 45 women; 84.2 ± 8.7 years). Forty of them were included in the Wii group (20 rehabilitation sessions during 8 consecutive weeks), and the other 40 were in the control group. -

Super Smash Bros. Tournament Rules

SUPER SMASH BROS. TOURNAMENT RULES General The Intramurals Participant Handbook will govern all aspects of play not considered playing rules of the sport. Participants are expected to follow the Handbook rules of conduct as well as the sport-specific rules outlined below. The Handbook is available at und.edu/intramurals. Key Handbook items include: • Registration & Payment – Handbook pg. 7 • Captain Responsibilities – Handbook pg. 9 • Team Name Requirements – Handbook pg. 10 • Playoff Requirements – Handbook pg. 12 • Default/Forfeit Instructions and Consequences – Handbook pg. 14 • Participant Eligibility/ID Requirements – Handbook pg. 15 • Adding Players to Roster/Participation Limits – Handbook pg. 18 • Team/Participant Conduct – Handbook pg. 21 • Nexus Policies – UND.edu/esports Schedules Schedules for league play are posted online through wellnessregistration.und.edu. Facility All games will be played at the Wellness Center Esports Nexus, or at remote locations. Questions Please feel free to contact UND Esports Nexus staff with any questions or concerns. Mike Wozniak Coordinator of Campus 701-777-3256 [email protected] Recreation Seb Reese Esports Program Manager 701-777-0212 [email protected] Wellness Center 701-777-9355 Revised 8/21/2020 UND Super Smash Bros. Rules Page 1 Equipment • We will be using Wellness & Health Promotion Nintendo Switch consoles, with the possibility of a loaned console if needed to facilitate competition. • We will have Joy-Cons and Switch Pro controllers to use if needed, however participants will be allowed to bring their own controllers. • Allowed controllers are: • GameCube • Switch Pro • Joy-Con • SmashBox • If you have another controller you wish to use, it will need to be approved by the Esports staff. -

Using the Nintendo Wii ® to Teach Human Factors Principles

AC 2009-1414: USING THE NINTENDO WII ® TO TEACH HUMAN FACTORS PRINCIPLES Lesley Strawderman, Mississippi State University Lesley Strawderman is an assistant professor in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering. She conducts research in the area of human factors and ergonomics, specifically looking at the impact of large scale service systems on human use. She has received her IE degrees from Penn State and Kansas State Universities. Page 14.1334.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2009 Using the Nintendo Wii ® to teach Human Factors Principles Abstract This paper describes how to use of the Nintendo Wii® game console to teach students a variety of human factors principles. First, the concept of Signal Detection Theory (SDT) is explained using a personalized searching game on the Wii®. Next, an activity involving human sensory systems is discussed. Finally, a learning module that addresses control design and feedback, focusing on the game’s controller (Wii Remote or Wiimote) is presented. Potential topic areas for future activities, including human computer interaction, are also discussed. The teaching activities described in this paper have been successfully used by the author in past semesters. A sampling of student feedback is provided in the paper. Finally, a discussion of how the activities could be extended to non-human factors courses and outreach activities is presented. Introduction The Nintendo Wii is a popular video game console that allows the player to interact with the games in many new ways. The focus of the Wii gaming system is its controller, called a Wii Remote. The wireless device functions much like a remote control, but has motion detecting technology that allows players to interact with the Wii games using motions. -

Wii Fit– Or Just a Wee Bit?

Wii Fit– Or Just A Wee Bit? By Alexa Carroll, M.S., ast Christmas, Chris Lee and his wife Julie bought a Nintendo Wii John Porcari, Ph.D., video game system as a gift for their three kids, ages 4 to 9. It was and Carl Foster, Ph.D., an immediate hit with the family, and soon after, they also pur- with Mark Anders Lchased Wii Fit, an exer-game for the Wii that focuses on strength training, aerobics, yoga and balance games performed using a small white balance board that looks similar to a household body-weight scale. “It sounded like a fun way to get the kids to of all time. These stats are encouraging, given the exercise and become aware of fitness without well-publicized epidemic of childhood obesity in being draconian or burdensome,” recalls Chris. our country and the fact that obesity and its com- “My oldest daughter took to it right away. My plications cause as many as 300,000 premature wife and I came around a bit more slowly after deaths each year, second only to cigarette smoking watching and helping the kids.” as a cause of death. For the past nine months, the Lees have used Now, assuming folks are using the Wii Fit exer- Wii Fit at least a few times a week, doing yoga, game as a substitute for their normally sedentary weighing in, charting their fitness progress, and screen-time, these numbers are good news. But having family challenges in ski jumping and on just how good? To give the public perspective on the rope course balance games. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2008 (Briefing Date: 2009/1/30) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2005 FY3/2006 FY3/2007 FY3/2008 FY3/2009 Apr.-Dec.'04 Apr.-Dec.'05 Apr.-Dec.'06 Apr.-Dec.'07 Apr.-Dec.'08 Net sales 419,373 412,339 712,589 1,316,434 1,536,348 Cost of sales 232,495 237,322 411,862 761,944 851,283 Gross margin 186,877 175,017 300,727 554,489 685,065 (Gross margin ratio) (44.6%) (42.4%) (42.2%) (42.1%) (44.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 83,771 92,233 133,093 160,453 183,734 Operating income 103,106 82,783 167,633 394,036 501,330 (Operating income ratio) (24.6%) (20.1%) (23.5%) (29.9%) (32.6%) Other income 15,229 64,268 53,793 37,789 28,295 (of which foreign exchange gains) (4,778) (45,226) (26,069) (143) ( - ) Other expenses 2,976 357 714 995 177,137 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (174,233) Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 115,359 146,694 220,713 430,830 352,488 (Income before income taxes and extraordinary items ratio) (27.5%) (35.6%) (31.0%) (32.7%) (22.9%) Extraordinary gains 1,433 6,888 1,047 3,830 98 Extraordinary losses 1,865 255 27 2,135 6,171 Income before income taxes and minority interests 114,927 153,327 221,734 432,525 346,415 Income taxes 47,260 61,176 89,847 173,679 133,856 Minority interests -91 -34 -29 -83 35 Net income 67,757 92,185 131,916 258,929 212,524 (Net income ratio) (16.2%) (22.4%) (18.5%) (19.7%) (13.8%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Successful Outreach with Mobile Gaming

Successful Outreach With Mobile Gaming Presented by Amanda Schiavulli Education and Outreach Librarian Finger Lakes Library System Goals • Participants will – Understand why play is important. – Comprehend what to expect when adding gaming to their collection. – Feel confident in finding gamers in their community. – Recognize Nintendo StreetPass and how it works for Outreach. – Find comfort in using gaming in their summer programming. Mobile Gaming http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/ESA_EF_2014.pdf Family Literacy Grant 2013- 2016 “Summer Reading at New York Libraries through Public Library Systems” – Year one 2013-2014 • Unbound Media – Year two 2014-2015 • Tablet Tales – Year three 2015-2016 • Gaming Project Objectives • Giving reluctant readers access to a new media • Giving strong readers a tool to advance their literacy levels • Pairing print, audio and video that will enhance retention, comprehension, attentiveness, reading level and reading speed. • Improving access to library materials and activities that encourage lifelong library learning and library use. • Libraries will perform outreach to local schools and daycares promoting the summer reading program. • Library staff will promote summer programming through the Nintendo 3DS StreetPass feature. • Children and their caregivers will engage in summer programming using the Nintendo 3DS. • The Nintendo 3DS StreetPass Feature will attract new users to the libraries • Children and their caregivers will work together to solve problems and advance in a variety of different games to promote literacy. What I will need from you in July: • Number of gaming programs held at your library • Number of participants attending a gaming event. • Number of StreetPasses from each 3DS. • Number of publicity announcements created and distributed via print and electronic means. -

Super Mario Galaxy Game Disc Into the Disc You’Ll Control Mario As He Ventures from the Comet Slot on Your Wii Console

INSTRUCTION BOOKLET PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. WARNING – Seizures • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or patterns, and this may occur while they are watching TV or playing video games, even if they have never had a seizure before. • Anyone who has had a seizure, loss of awareness, or other symptom linked to an epileptic condition should consult a doctor before playing a video game. • Parents should watch their children play video games. Stop playing and consult a doctor if you or your child has any of the following symptoms: Convulsions Eye or muscle twitching Altered vision Loss of awareness Involuntary movements Disorientation • To reduce the likelihood of a seizure when playing video games: 1. Sit or stand as far from the screen as possible. 2. Play video games on the smallest available television screen. 3. Do not play if you are tired or need sleep. 4. Play in a well-lit room. 5. Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour. WARNING – Repetitive Motion Injuries and Eyestrain Playing video games can make your muscles, joints, skin or eyes hurt. Follow these instructions to avoid problems such as tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, skin irritation or eyestrain: • Avoid excessive play. Parents should monitor their children for appropriate play. • Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour, even if you don’t think you need it. -

A Pilot Trial of a Videogame-Based Exercise Program for Methadone Maintained Patients

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 47 (2014) 299–305 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment Brief article A pilot trial of a videogame-based exercise program for methadone maintained patients Christopher J. Cutter, Ph.D. a,b,⁎, Richard S. Schottenfeld, M.D. a, Brent A. Moore, Ph.D. a, Samuel A. Ball, Ph.D. a, Mark Beitel, Ph.D. a,b, Jonathan D. Savant, B.S. b, Matthew A. Stults-Kolehmainen, Ph.D. c, Christopher Doucette, B.A. b, Declan T. Barry, Ph.D. a,b a Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT 06511 United States b Pain Treatment Services, APT Foundation, Inc., New Haven, CT 06519 United States c Northern Illinois University, IL 60115 United States article info abstract Article history: Few studies have examined exercise as a substance use disorder treatment. This pilot study investigated the Received 23 October 2013 feasibility and acceptability of an exercise intervention comprising the Wii Fit Plus™ and of a time-and- Received in revised form 7 May 2014 attention sedentary control comprising Wii™ videogames. We also explored their impact on physical activity Accepted 12 May 2014 levels, substance use, and psychological wellness. Twenty-nine methadone-maintained patients enrolled in an 8-week trial were randomly assigned to either Active Game Play (Wii Fit Plus™ videogames involving Keywords: ™ Opioid-related disorders physical exertion) or Sedentary Game Play (Wii videogames played while sitting). Participants had high Exercise satisfaction and study completion rates. Active Game Play participants reported greater physical activity Video games outside the intervention than Sedentary Game Play participants despite no such differences at baseline. -

Super Smash Bros. for Wii U That You've Unlocked

1 Importan t Informati on Gtget in Srdta te 2 Supporte d Controlle rs 3 amiibo 4 Internet Enhancemen ts 5 Note to Par ents and Guardi ans TeBh aiss c 6 What K ind of Game I s Th is? 7 Srnta ti g a Gam e 8 Saving an d Deleting D ata Actio ns ( Wii U Ga mePa d) 9 Meov mten 10 Aatt ckgin 11 Shields WUP-P-AXFE-04 Actions (For Other Controlle rs) 12 Meov mten 13 Atta cki ng/Shie ldi ng Sett ing Up a Mat ch 14 Sitart ntg Ou 15 Bsca i Rlsu e 16 Items Mode I ntroducti on 17 Smash 18 Oinl ne (Bt)at le 19 Online (Spec tator/Share /Even ts) 20 Sahm s Toru 21 Games & M ore (Solo/Gro up) 22 Geamus & More (Cts om /e Steag Build)r 23 Games & Mor e (Vault/Optio ns) Other 24 CnonnNeict go t intdenSeoD 3 Systsm 25 Play ing with a mii bo 26 Post ing to Mii ver se 27 Download able Conte nt Fhig tser 28 Mario/Donke y Kong/Link/Sa mus 29 YhKos i/ ir/xby Fo 30 Pikachu/Lui gi/Captain Fal con 31 Ness/Jig glypuff/Pea ch 32 Bows er/ Zelda/ She ik 33 Marth/ Gano ndorf/Meta Knight 34 Pit/Z ero Suit Samus/I ke 35 Crhadirza di/D dy Kgone/nKi ge D ded 36 Olimar/Lu cario/Toon L ink 37 Vlai lgrWe / ii FitTa r ie/n rLRslo a ia&n um a 38 Little Mac/ Greninja/Palut ena 39 Robin /Shu lk/Bows er J r.