Steam Engine Time 1 Steam Engine T Ime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rediscovery of Man Free Download

THE REDISCOVERY OF MAN FREE DOWNLOAD Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man Sure, I can say it has pages of acclaimed stories—every short story that Cordwainer Smith ever wrote. After defeat, after disappointment, after ruin and reconstruction, mankind had leapt among the stars. The Rediscovery of Man Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith. The majority of these stories take place 14, yeas into the future, and The Rediscovery of Man this day, present a The Rediscovery of Man worldview, and an astounding examination of human nature. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This brilliant collection, often cited as the first of its kind, explores fundamental questions about ourselves and our treatment of the universe and other beings around us and ultimately what it means to be human. Cordwainer Smith is a writer like none other. These stories were written in the late 50s, early 60s, and are so intelligent and forward thinking, I'm still stunned. Underpeople do all the hard work, police is made up of robots and telepathic mind control checks that everybody is thinking happy thoughts, or they are sent for re-education. A Cordwainer Smith Panel Discussion. That said, when I said last time that I was relieved that Tiptree's radical feminism never crossed the line into open transphobia, a finger on the monkey's paw curled up and delivered me Smith's "The Tranny Menace from Beyond the Stars" "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal," about which I have absolutely nothing positive to say. -

Asimov on Science Fiction

Asimov On Science Fiction Avon Books, 1981. Paperback Table of Contents and Index Table of Contents Essay Titles : I. Science Fiction in General 1. My Own View 2. Extraordinary Voyages 3. The Name of Our Field 4. The Universe of Science Fiction 5. Adventure! II. The Writing of Science Fiction 1. Hints 2. By No Means Vulgar 3. Learning Device 4. It’s A Funny Thing 5. The Mosaic and the Plate Glass 6. The Scientist as Villain 7. The Vocabulary of Science Fiction 8. Try to Write! III. The Predictions of Science Fiction 1. How Easy to See The Future! 2. The Dreams of Science Fiction IV. The History of Science Fiction 1. The Prescientific Universe 2. Science Fiction and Society 3. Science Fiction, 1938 4. How Science Fiction Became Big Business 5. The Boom in Science Fiction 6. Golden Age Ahead 7. Beyond Our Brain 8. The Myth of the Machine 9. Science Fiction From the Soviet Union 10. More Science Fiction From the Soviet Union Isaac Asimov on Science Fiction Visit The Thunder Child at thethunderchild.com V. Science Fiction Writers 1. The First Science Fiction Novel 2. The First Science Fiction Writer 3. The Hole in the Middle 4. The Science Fiction Breakthrough 5. Big, Big, Big 6. The Campbell Touch 7. Reminiscences of Peg 8. Horace 9. The Second Nova 10. Ray Bradbury 11. Arthur C. Clarke 12. The Dean of Science Fiction 13. The Brotherhood of Science Fiction VI Science Fiction Fans 1. Our Conventions 2. The Hugos 3. Anniversaries 4. The Letter Column 5. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

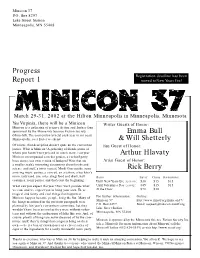

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

S67-00104-N218-1995-07 08.Pdf

Issue 1218, July/August 1995 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: President's Message (Sanders) 3 Minutes of Meeting Between Members of SmA and IAFA at the Annual ICFA (Gordon) 3 Corrections/Additions 4 SmA Members & Friends 5 Editorial (Sisson) 5 NEWS AND INFORMATION 7 SPECIAL FEATURE: "The Worlds of David Lynch": Lavery, David (Ed). Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to 7Win Peaks. (Davis) 11 Gifford, Barry. Hotel Room Trilogy; and Lynch, David. David Lynch's Hotel Room. (umland) 13 SPECIAL FEATURE: "Lovecraft the Man": Lovecraft, H.P. (S.T. Joshi, Ed). Miscellaneous Writings. (Anderson) 17 Squires, Richard D. Stern Fathers 'neath the Mould: The Lovecraft Family in Rochester. (Bousfield) 20 Barlow, Robert H. and H.P. Lovecraft (S.T. Joshi, Ed). The Hoard of the Wizard Beast and One Other; and Joshi, S.T. & David schultz (Eds). H.P. Lovecraft Letters 7b SaJIlJel Loveman & vincent Starrett (Kaveny) 21 REVIEWS: Nonfiction: Barron, Neil (Ed). Anato~ Of Wonder, 4th Edition. (Kaveny & Bogstad) 23 Heller, Steven and Seynour Chwast. Jackets Required: An Illustrated History of American Book Jacket Design, 1920-1950. (Barron) 27 Kessler, carol Farley. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: her progress toward utopia with selected writings. (Orth) 29 Korshak, Stephen D. (Ed). A Hannes Bok Showcase. (Albert) 34 McCarthy, Helen. AniIoo J : A Beginner's Guide to Japanese Animation. (Klossner) 35 SFRA Re\liew#218. July/August 1995 Scheick, william J. (Ed). The Critical Resp:Jnse to H.G •. ~lls. (Huntington) 36 Schlobin, Roger C. and Irene R. Harrison. Andre Norton: A primaIy and Secondary Bibliography (Bogstad) 38 silver, Alain and Janes Ursini. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 6-1-2006 SFRA ewN sletter 276 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 276 " (2006). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 91. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #~T. April/llay/June J006 • Editor: Christine Mains Hanaging Editor: Janice M. Boastad Nonfiction Reriews: Ed McKniaht Science Fiction Research Fiction Reriews: Association Philip Snyder SFRA Re~;e", The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068-395X) is published four times a year by the Science Fiction ResearchAs I .. "-HIS ISSUE: sodation (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale; however, starting with issue SFRA Business #256, all issues will be published to SFRA's website no less than 10 weeks Editor's Message 2 after paper publication. For information President's Message 2 about the SFRA and its benefits, see the Executive Meeting Minutes 3 description at the back of this issue. For a membership application, contact SFRA Business Meeting Minutes 4 Treasurer Donald M. Hassler or get one Treasurer's Report 7 from the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

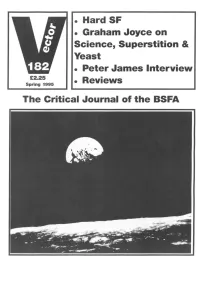

Hard SF • Graham Joyce on Science, Superstition & Yeast

• Hard SF • Graham Joyce on Science, Superstition & Yeast • Peter James Interview £2.25 Spring 1995 • Reviews The Critical Journal of the BSFA 2 Vector Contents Remember PeIe1 James Interview Check the address label MartinRWebb How Ha,d IS SF? on your mailing to see if Paul Kincaid 14 Science, Supersl1lion & Strange you need to renew your Things Like Yeast Graham Jo,,ce subscription 20 Reviews Index 21 First lmpre~ions Reviews edited by Paul Kincaid 30 Paperback Grnff111 Vector Is published l7j the BSr/\ ,.,11995 Reviews edilec.l lly Stept1er1 Pt!yne /\II opinions are those of the 1nd1v1dua! con1r1bu t01 and should not be taken necessanly to be those of 1110 ed1toI or the BSFA. Editor Catie Ca1y 224 Soulhway, Park Barn, Guildford, Contr,bul,ons &111ey. GU2 SON Good a1 t1Cles are always wanted All MSS shoo Id be Phone; 0483 502349 typed double spaced on one srje ol the page SubmlSSIOns may also be accepted as ASCII text files Hardback Rev10WS on IBM, Afan ST or Mac 3.5• discs. Paul Kincaid Maximum prelerred length IS 6CXX) words; exceplons 60 Bournemouth Rd, Folkestone, Kent. CT 19 5AZ can and will be made. A Pfehm1nary letter IS ad'visable but not essent1al. Unsol1e1ted MSS cannot be returned Paperback Reviews Ed1to1 without an SAE. Stephen Payne Please note lhal !here is no payment fo, pubhcat10n. 24 Malvern Rd, Stoneygate, Leiceste1, LE2 28H Members who wish to ffNl&N books should fusl write to the appropriate echlor. Magazme Reviews Editor Maureen Kmca1d Speller Ar lists 60 Bournemouth Rd, Folkestone, Kent, CT 19 5AZ Cover Art, Illustrations and Fillers are always welcome Editorial Assistants The British Science Fiction Association ltd - Com Alan Johnson. -

Science Fictional the Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre

Science Fictional The Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre Andrew Frost University of NSW | College of Fine Arts PhD Media Arts 2013 4 PLEASE TYPE Tl<E UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Tht:tltiDittorUdon Sht•t Surname or Fenily name: Frost FIRI neme; Andrew OCher namels: Abbr&Yia~lon fof" dcgrco as given in the Unlverslty caltn<S:ar. PhD tCOde: 1289) Sd'IOOI; Seh.ool Of Media Arts Faculty; Coll999 of A ne Am Title: Science Fletfonar.: The AestheUes or SF Beyond the Limit:t of Gcnt'O. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) ScMtnce Flcdonal: The Anthetics of SF Beyond the Umlts of Genre proposes that oonte~my eufture 1$ * $pallal e)Cl>ertence dom1nS'ed by an aesane(IC or science liction and its qua,;.genefic form, the ·$dence ficdonal', The study explores the connective lines between cultural objects suet! as film, video art. painting, illustration, advertising, music, and children's television in a variety ofmediums and media coupled with research that conflates aspects of ctitical theory, art history a nd cuttural studies into a unique d iscourse. The study argues thai three types of C\lltural e ffeets reverberation. densi'ly and resonanoe- affect cultural space altering ood changing the 1ntel'l)totation and influeooe of a cuUural object Through an account of the nature of the science fictional, this thesis argues that science fiction as wo uncJersland It, a.nd how 11 has beon oooventionally concefved, is in fact the counter of its apparent function within wider culture. While terms such as ·genre~ and ·maln-stream• suggest a binary of oentre and periphery, this lh-&&is demonstrates that the quasi-generic is in fact the dominant partner in the process of cultural production, Ocelamlon ,.~ lo disposition or projoct thnlsJdtuen.tlon I htrOby grltlt t<> I~ Ul'll\IOI'IiiY Of Now SOUIJ'I WaltS or i&& agents the rlg:tlllo ard'llve anct to INike available my ttwrsl9 or di$sertabon '" whole or in 1»Jt il'lllle \Jtlivetsay lbrsrles., at IOtmS Of tnedb, rtOW or hero <~~Ot kncwn, 5tAijod:.lo lho Jl«Mdonll ol lho Co9yrlghlt Act 1968.