The Freeman 1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tethered a COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album

Tethered A COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album Letters to You From Jesus To Give You HOPE and INSTRUCTION as given to Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois as well as Carol Jennings Edited and Compiled by Carol Jennings Cover Illustration courtesy of: Ain Vares, The Parable of the Ten Virgins www.ainvaresart.com Copyright © 2016 Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois Published by Heartdwellers.org All Rights Reserved. 2 NOTICE: You are encouraged to distribute copies of this document through any means, electronic or in printed form. You may post this material, in whole or in part, on your website or anywhere else. But we do request that you include this notice so others may know they can copy and distribute as well. This book is available as a free ebook at the website: http://www.HeartDwellers.org Other Still Small Voice venues are: Still Small Voice Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/claredubois/featured Still Small Voice Facebook: Heartdwellers Blog: https://heartdwellingwithjesus.wordpress.com/ Blog: www.stillsmallvoicetriage.org 3 Foreword…………………………………………..………………………………………..………….pg 6 What Just Happened?............................................................................................................................pg 8 What Jesus wants you to know from Him………………………………………………………....pg 10 Some questions you might have……………………………………………………….....................pg 11 *The question is burning in your mind, ‘But why?’…………………....pg 11 *What do I need to do now? …………………………………………...pg 11 *You ask of Me (Jesus) – ‘What now?’ ………………………….….....pg -

2020 Music Performance Written Examination

Victorian Certificate of Education SUPERVISOR TO ATTACH PROCESSING LABEL HERE 2020 Letter STUDENT NUMBER MUSIC PERFORMANCE Aural and written examination Friday 27 November 2020 Reading time: 11.45 am to 12.00 noon (15 minutes) Writing time: 12.00 noon to 1.30 pm (1 hour 30 minutes) QUESTION AND ANSWER BOOK Structure of book Section Number of Number of questions Number of questions to be answered marks A 3 3 28 B 9 9 46 C 6 6 26 Total 100 • Students are permitted to bring into the examination room: pens, pencils, highlighters, erasers, sharpeners and rulers. • Students are NOT permitted to bring into the examination room: blank sheets of paper and/or correction fluid/tape. • No calculator is allowed in this examination. Materials supplied • Question and answer book of 19 pages, including blank manuscript for rough work on page 13 • An audio compact disc containing musical excerpts for Sections A and B Instructions • Write your student number in the space provided above on this page. • You may write at any time during the running of the audio compact disc and after it stops. • All written responses must be in English. Students are NOT permitted to bring mobile phones and/or any other unauthorised electronic devices into the examination room. © VICTORIAN CURRICULUM AND ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY 2020 2020 MUSIC PERFORMANCE EXAM 2 SECTION A – Listening and interpretation Instructions for Section A Answer all questions in pen or pencil in the spaces provided. An audio compact disc will run continuously throughout Section A. Question 1 (8 marks) Work: ‘A World First’ by David Hirschfelder Performers: Studio ensemble conducted by Brett Kelly Album: Ride Like a Girl: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (David Hirschfelder, 2019) The excerpt will be played three times. -

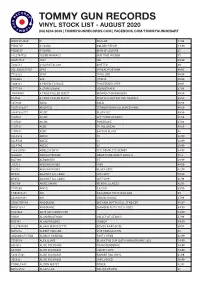

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I -

Sf Commentary 85

SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages IN THIS ISSUE: Jennifer BRYCE Elaine COCHRANE DITMAR (Dick JENSSEN) Brad FOSTER Bruce GILLESPIE Steve JEFFERY Patrick McGUIRE Mark PLUMMER Steve STILES Taral WAYNE Ray WOOD AND MANY MORE! Cover: ‘The Alien Race’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) SF COMMENTARY 85 October 2013 92 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 85, October 2013, is edited and published in a limited number of print copies by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3068, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. Preferred means of distribution .PDF file from eFanzines.com at: Portrait edition (print equivalent): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85P.PDF or Landscape edition (widescreen): http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC85L.PDF or from my email address: [email protected]. Front cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘The Alien Race’. Back cover: Steve Stiles: ‘Lovecraft’s Fever Dream’. Artwork Taral Wayne (p. 47); Steve Stiles (p. 52); Brad W. Foster (p. 58). Photographs Peggyann Chevalier (p. 3); Murray and Natalie MacLachlan (p. 4); Helena Binns (p. 26); Barbara Lamar (p. 46); Mervyn and Helena Binns (p. 56); Harold Cazneaux, courtesy Ray Wood (p. 71). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS 45 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (cond.) 4 Friends lost in 2013 4 The Sea and Summer returns Doug Barbour :: Damien Broderick :: Taral Wayne :: John Litchen :: Michael Bishop :: Yvonne Editor Rousseau :: Kaaron Warren :: Tim Marion :: Steve Sneyd :: George Zebrowski :: 5 FAVOURITES 2012 Franz Rottensteiner :: Paul Anderson :: Favourite books of 2012 Sue Bursztynski :: Martin Morse Wooster :: Favourite novels of 2012 Andy Robson :: Jerry Kaufman :: Rick Kennett Favourite short stories of 2012 :: Lloyd Penney :: Joseph Nicholas :: Casey Wolf :: Murray Moore :: Jeff Hamill :: David Lake :: Favourite films of 2012 Pete Young :: Gary Hoff :: Stephen Campbell :: Favourite films re-seen in 2012 John-Henri Holmberg :: David Boutland Television (?!) 2012 (David Rome) :: Matthew Davis :: Favourite filmed music documentaries 2012 William Breiding :: We Also Heard From .. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2011-2012

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE ANNUAL REPORT 2011/12 Multi-award winning German design collective, URBANSCREEN was commissioned as part of Vivid LIVE to create a new artwork that explored both the iconic sculptural form of Sydney Opera House, as well as its place as a home for music, dance and drama. Contents 5 Who We Are 5 Letter to Minister 6 Highlights 8 Chairman’s Message 10 CEO’s Message 12 Vision and Goals 14 Our History 16 Outcomes and Objectives 20 Goal 1: Artistic Excellence 22 Sydney Opera House Presents 30 Resident and Supported Companies Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2011/12 Annual Report House Opera Sydney 36 Goal 2: Community Engagement and Access 38 Community Outreach and Participation 40 Beyond Bennelong 44 Customer Service and Access 46 Goal 3: A Vibrant and Sustainable Site 48 Our Precinct 50 Venues, Building and Site 52 Environmental Sustainability 54 Safety and Security 56 Goal 4: Earning Our Way 58 Governance 60 Trust Members 62 Executive Team 64 People and Culture 66 Financial Overview 70 Financial Statements 100 Government Reporting 124 Performance List 128 Donors Acknowledgement 130 Contact Information 131 Site Map 132 Index 134 Corporate Partners 4 Introduction Sydney Opera House is a global icon, We are also a community symbol that the most internationally recognised unites Australians from all geographic, symbol of Australia and one of the great cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. buildings of the world. Nationwide research has shown that 95% of Australians, wherever they live, see We are committed to continuing the Sydney Opera House as a national icon legacy of Utzon’s creative genius by and a source of national pride. -

The Performance of Politics

The Performance of Politics 000_Alexander_FM.indd0_Alexander_FM.indd i 66/17/2010/17/2010 110:20:020:20:02 PPMM 000_Alexander_FM.indd0_Alexander_FM.indd iiii 66/17/2010/17/2010 110:20:020:20:02 PPMM The Performance of Politics Obama’s Victory and the Democratic Struggle for Power QW jeffrey c. alexander 1 2010 000_Alexander_FM.indd0_Alexander_FM.indd iiiiii 66/17/2010/17/2010 110:20:020:20:02 PPMM 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alexander, Jeffrey C., 1947 The performance of politics : Obama’s victory and the democratic struggle for power / Jeffrey C. Alexander. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-974446-6 1. Presidents—United States—Election—2008. 2. Obama, Barack. 3. -

Yeats's Mask: Yeats Annual No

YEATS’S LEGACIES Yeats Annual No. 21: A Special Issue Edited by WARWICK GOULD To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/724 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3–8, 10–11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould THE LIVING STREAM YEATS ANNUAL No. 18: A Special Issue Essays in Memory of A. Norman Jeffares Edited by Warwick Gould Freely available at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 YEATS’S MASK YEATS ANNUAL No. 19: A Special Issue Edited by Margaret Mills Harper and Warwick Gould Freely available at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/233 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF EAMONN CANTWELL YEATS ANNUAL No. 20: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould Freely available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/380 YEATS ANNUAL No.