Bel at Palmyra and Elsewhere in the Parthian Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments of Terrorism: (De)Selecting Memory and Symbolic Exchange at the Interface Between Westminster and Raqqa

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 2 (2020) Monuments of Terrorism: (De)Selecting Memory and Symbolic Exchange at the Interface Between Westminster and Raqqa Theodore Price Contemporary conflict is conducted across multiple visual fronts, as the old visual symbols of conventional warfare and remembrance are increasingly replaced with digital images. Focusing on three events in the summer of 2015: the attack on tourists in Tunisia, the blowing up of the Temple of Bel in Palmyra, Syria, and the construction of a replica of the destroyed Arch of Triumph from Palmyra in Trafalgar Square, London, this paper details the symbolic exchange between the so-called Islamic State and western governments. Through an examination of the visual representation of violence enacted towards individual holidaymakers and ancient tourist sites, this paper details how the attack on a holiday resort in Tuni- sia was recast through a master narrative of war where the military repatriation of civilians represented the dead tourists as fallen soldiers. It will examine the visual record of the destruction of the Temple of Bel, by the Islamic State (ISIS), arguing that this action gained international legitimacy through the validation and complicity of the visual frame provided by satellite images from the United Na- tions. Finally, it will discuss the replication of the Arch of Triumph, from Palmyra, in Trafalgar Square as a further example of the instrumentalisation of counter- iconoclasm. In this paper I suggest that the new monuments to terrorism are images of the events themselves, rather than simply physical memorials built for remem- brance, and that these new monuments to terrorism circulating within the virtual landscapes of the internet, become the new sites of collective memorialisation Theodore Price is a London-based artist, curator and researcher whose practice is located at the intersection between art and politics. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Nabu 2015-2-Mep-Dc

ISSN 0989-5671 2015 N°2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 25) À propos d’ARET XII 344, des déesses dgú-ša-ra-tum et de la naissance du prince éblaïte* — Le texte administratif ARET XII 344 est malheureusement assez lacuneux, mais à notre avis quand même très intéressant. Les lignes du texte préservées sont les suivantes: r. I’:1’-5’: ‹x›[...] / šeš-[...] / in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*-mu*] v. II’:1’-11’: ...] K[ALAM.]KAL[AM(?)] / NI-šè-na-⸢a⸣ / ma-lik-tum / è / é / daš-dar / ap / íl-'à- ag-da-mu / i[n] / [...] / [...] r. III’:1’-9’: ⸢'à⸣-[...] / 1 gír mar-t[u] zú-aka / 1 buru₄-mušen 1 kù-sal / daš-dar / NAM-ra-luki / 1 zara₆-túg ú-ḫáb / 1 giš-šilig₅* 2 kù-sig₁₇ maš-maš-SÙ / 1 šíta zabar / dga-mi-iš r. IV’:1’-10’: ⸢x⸣[...] / 10 lá-3 an-dù[l] igi-DUB-SÙ šu-SÙ DU-SÙ kù:babbar / 10 lá-3 gú-a-tum zabar / dgú-ša-ra-tum / 5 kù-sig₁₇ / é / en / ni-zi-mu / 2 ma-na 55 kù-sig₁₇ / sikil r. V’:1’-6’: [x-]NE-[t]um / [x K]A-dù-gíd / [m]a-lik-tum / i[n-na-s]um / dga-mi-iš / 1 dib 2 giš- DU 2 ti-gi-na 2 geštu-lá 2 ba-ga-NE-su!(ZU) r. VI’:1’-6’: [...]⸢x⸣ / [m]a-[li]k-tum / [šu-ba₄-]ti / [x ki]n siki / [x-]li / [x-b]a-LUM. Tout d’abord, on remarquera qu’au début du texte on peut lire in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*- mu*], c’est-à-dire « dans le jour de la fête (en l’honneur) d’íl-'à-ag-da-mu ». -

Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 31 | 2018 Varia Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon Eva Anagnostou‑Laoutides and Michael B. Charles Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2653 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2653 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 9-37 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Eva Anagnostou‑Laoutides and Michael B. Charles, “Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon”, Kernos [Online], 31 | 2018, Online since 01 October 2020, connection on 24 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2653 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ kernos.2653 This text was automatically generated on 24 January 2021. Kernos Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon 1 Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon Eva Anagnostou‑Laoutides and Michael B. Charles In this article, abbreviations follow the “Liste des périodiques” in L’Année philologique. Other abbreviations are as per OCD 3. Translations of ancient texts are attributed to their respective translator as they are used. Introduction 1 The article examines two passages in Herodotus: a) his description of the ziggurat at Babylon (1.181.5–182.1–2 and 1.199), which has been often quoted as corroborating evidence for the practice of “sacred marriages” in the ancient Near East;1 and b) his description -

NABU 2021 2 Compilé 07 Corr NZ

ISSN 0989-5671 2021 N° 2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 26) Kings’ ladies at Ebla’s court — The label ‘dam en list’ is used to refer to sections of several administrative tablets mentioning the female members of the Ebla royal family. These women appear in the documents along with other members of the court as the recipients of garments and/or precious objects. Three new, complete lists of dam en have been published since the last comprehensive study on the topic by Tonietti (1989), and several fragmentary lists appeared in Lahlou and Catagnoti (2006). In this note I shall offer an updated index of the dam en lists, providing a few general remarks which might facilitate access to this material to a non-specialist public. The group of women mentioned in the dam en lists includes different female members of the royal family. While Sumerian differentiates between human and non-human, Eblaite and other Semitic languages have two grammatical genders. We thus translate the Sumerian term dam (“spouse”) as “wife” or “(adult) woman” depending on the context. However, the scribes of the Archives used the label dam en rather inconsistently, at times including in this group women who had a different kin relationship with the king (Biga 1987). Three facts corroborate this statement. First, in some lists, such as R₁ (see Table 1) the scribes made a clear distinction between the king’s wives, addressed as dam en (Raʿutum, Kiršūt, Ḥinna-Šamaš, Rapeštum, Mašgašatu, Maqaratu, Tašma-Damu, Rapeštum-II), his daughters who are called dumu-mi₂ en (Maʾut, Ṣanīʿī-Mari), as well as several other high ranking women. -

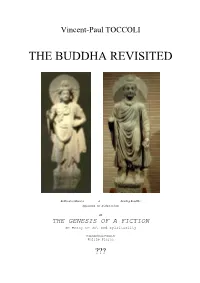

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions

MISCELLANEOUS BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS BY GEORGE A. BARTON PROFESSOR IN BRYN MAWR COLLEGE ttCI.f~ -VIb NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVIII COPYRIGHT 1918 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published, August, 191 8. TO HAROLD PEIRCE GENEROUS AND EFFICIENT HELPER IN GOOD WORKS PART I SUMERIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE The texts in this volume have been copied from tablets in the University Museum, Philadelphia, and edited in moments snatched from many other exacting duties. They present considerable variety. No. i is an incantation copied from a foundation cylinder of the time of the dynasty of Agade. It is the oldest known religious text from Babylonia, and perhaps the oldest in the world. No. 8 contains a new account of the creation of man and the development of agriculture and city life. No. 9 is an oracle of Ishbiurra, founder of the dynasty of Nisin, and throws an interesting light upon his career. It need hardly be added that the first interpretation of any unilingual Sumerian text is necessarily, in the present state of our knowledge, largely tentative. Every one familiar with the language knows that every text presents many possi- bilities of translation and interpretation. The first interpreter cannot hope to have thought of all of these, or to have decided every delicate point in a way that will commend itself to all his colleagues. The writer is indebted to Professor Albert T. Clay, to Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., and to Dr. Stephen Langdon for many helpful criticisms and suggestions. Their wide knowl- edge of the religious texts of Babylonia, generously placed at the writer's service, has been most helpful. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Fragmentation of Being and the Path Beyond the Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D

DRAFT Fragment 48 THE HOUSE OF BAAL Next we will consider the house of Baal who is the twin of Agenor. Agenor means the “manly,” whereas Baal means “lord.” In Baal is Belus. Within the Judeo- Christian religious tradition, Baal is the archetypal adversary to the God of the Old Testament. No strange god, however, is depicted more wicked, immoral and abominable than the storm god Ba’al Hadad, whose cult appears to have been a great rival to Yahwism at certain times in Israel’s history. In the bible we read how the prophets of Ba’al and Yahweh persecuted and killed one another, and how the kings of Israel wavered in their attitudes to these gods, thereby provoking the jealousy of Yahweh who tolerated no other god beside him. Thus, it appears that the worship of Ba’al Hadad was a greater threat to Yahwism than that of any other god, and this fact, perhaps more than the actual character of the Ba’al cult, may be the reason for the Hebrew aversion against it. The Fragmentation of Being and The Path Beyond The Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D. Palmer. All rights reserved. Not for distribution. THE HOUSE OF BAAL Whereas Ba’al became hated by the true Yahwist, Yahweh was the national god of Israel to whose glory the Hebrew Bible is written. Yahweh is also called El. That El is a proper name and not only the appelative, meaning “god” is proven by several passages in the Bible. According to the Genesis account, El revealed himself to Abraham and led him into Canaan where not only Abraham and his family worshiped El, but also the Canaanites themselves. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Neo-Assyrian Treaties As a Source for the Historian: Bonds of Friendship, the Vigilant Subject and the Vengeful King�S Treaty

WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY Sources, Problems, and Approaches Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Helsinki on September 22-25, 2014 Edited by G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger THE NEO-ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT 2019 STATE ARCHIVES OF ASSYRIA STUDIES Published by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki in association with the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Project Director Simo Parpola VOLUME XXX G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger (eds.) WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY SOURCES, PROBLEMS, AND APPROACHES THE NEO- ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT State Archives of Assyria Studies is a series of monographic studies relating to and supplementing the text editions published in the SAA series. Manuscripts are accepted in English, French and German. The responsibility for the contents of the volumes rests entirely with the authors. © 2019 by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki and the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research All Rights Reserved Published with the support of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Set in Times The Assyrian Royal Seal emblem drawn by Dominique Collon from original Seventh Century B.C. impressions (BM 84672 and 84677) in the British Museum Cover: Assyrian scribes recording spoils of war. Wall painting in the palace of Til-Barsip. After A. Parrot, Nineveh and Babylon (Paris, 1961), fig. 348. Typesetting by G.B. Lanfranchi Cover typography by Teemu Lipasti and Mikko Heikkinen Printed in the USA ISBN-13 978-952-10-9503-0 (Volume 30) ISSN 1235-1032 (SAAS) ISSN 1798-7431 (PFFAR) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. vii Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi, Raija Mattila, Robert Rollinger, Introduction ..............................