Intermediality and Media Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television and the Myth of the Mediated Centre: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Television Studies?

TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? Paper presented to Media in Transition 3 conference, MIT, Boston, USA 2-4 May 2003 NICK COULDRY LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Media@lse London school of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE UK Tel +44 (0)207 955 6243 Fax +44 (0)207 955 7505 [email protected] 1 TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? ‘The celebrities of media culture are the icons of the present age, the deities of an entertainment society, in which money, looks, fame and success are the ideals and goals of the dreaming billions who inhabit Planet Earth’ Douglas Kellner, Media Spectacle (2003: viii) ‘The many watch the few. The few who are watched are the celebrities . Wherever they are from . all displayed celebrities put on display the world of celebrities . precisely the quality of being watched – by many, and in all corners of the globe. Whatever they speak about when on air, they convey the message of a total way of life. Their life, their way of life . In the Synopticon, locals watch the globals [whose] authority . is secured by their very remoteness’ Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences (1998: 53-54) Introduction There seems to something like a consensus emerging in television analysis. Increasing attention is being given to what were once marginal themes: celebrity, reality television (including reality game-shows), television spectacles. Two recent books by leading media and cultural commentators have focussed, one explicitly and the other implicitly, on the consequences of the ‘supersaturation’ of social life with media images and media models (Gitlin, 2001; cf Kellner, 2003), of which celebrity, reality TV and spectacle form a taken-for-granted part. -

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Rte Guide Tv Listings Ten

Rte guide tv listings ten Continue For the radio station RTS, watch Radio RTS 1. RTE1 redirects here. For sister service channel, see Irish television station This article needs additional quotes to check. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Найти источники: РТЗ Один - новости газеты книги ученый JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) RTÉ One / RTÉ a hAonCountryIrelandBroadcast areaIreland & Northern IrelandWorldwide (online)SloganFuel Your Imagination Stay at home (during the Covid 19 pandemic)HeadquartersDonnybrook, DublinProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishIrishIrish Sign LanguagePicture format1080i 16:9 (HDTV) (2013–) 576i 16:9 (SDTV) (2005–) 576i 4:3 (SDTV) (1961–2005)Timeshift serviceRTÉ One +1OwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannKey peopleGeorge Dixon(Channel Controller)Sister channelsRTÉ2RTÉ News NowRTÉjrTRTÉHistoryLaunched31 December 1961Former namesTelefís Éireann (1961–1966) RTÉ (1966–1978) RTÉ 1 (1978–1995)LinksWebsitewww.rte.ie/tv/rteone.htmlAvailabilityTerrestrialSaorviewChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Freeview (Northern Ireland only)Channel 52CableVirgin Media IrelandChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 135 (HD)Virgin Media UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 875SatelliteSaorsatChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Sky IrelandChannel 101 (SD/HD)Channel 201 (+1)Channel 801 (SD)Sky UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 161IPTVEir TVChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 115 (HD)Streaming mediaVirgin TV AnywhereWatch liveAer TVWatch live (Ireland only)RTÉ PlayerWatch live (Ireland Only / Worldwide - depending on rights) RT'One (Irish : RTH hAon) is the main television channel of the Irish state broadcaster, Raidi'teilif's Siranne (RTW), and it is the most popular and most popular television channel in Ireland. It was launched as Telefes Siranne on December 31, 1961, it was renamed RTH in 1966, and it was renamed RTS 1 after the launch of RTW 2 in 1978. -

Marital and Familial Roles on Television: an Exploratory Sociological Analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1974 Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Charles Daniel, "Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis " (1974). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5984. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5984 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Privalomo Skaitmeninės Televizijos Retransliavimo Elektroninių Ryšių Tinklais Teisinis Reguliavimas

MYKOLO ROMERIO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINĖS INFORMATIKOS FAKULTETAS ELEKTRONINIO VERSLO KATEDRA DONATAS VITKUS Naujųjų technologijų teisė, NTTmns0-01 PRIVALOMO SKAITMENINĖS TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO ELEKTRONINIŲ RYŠIŲ TINKLAIS TEISINIS REGULIAVIMAS Magistro baigiamasis darbas Darbo vadovas – Doc. dr. Darius Štitilis Vilnius, 2011 TURINYS ĮVADAS .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1 PRIVALOMO TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO INSTITUTAS IR JO SVARBA ... 9 1.1 Televizijos techniniai aspektai ir rūšys ........................................................................ 9 1.2 Retransliavimo sąvokos identifikavimas .................................................................... 13 1.3 Privalomas paketas ir jo reikšmė ................................................................................ 15 2 PRIVALOMO SKAITMENINĖS TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO TEISINIS REGULIAVIMAS ES ŠALYSE ..................................................................................................... 19 2.1 Bendrasis „must carry“ reguliavimas ES ................................................................... 19 2.2 Austrija ....................................................................................................................... 21 2.3 Vokietija ..................................................................................................................... 22 2.4 Jungtinė Karalystė ..................................................................................................... -

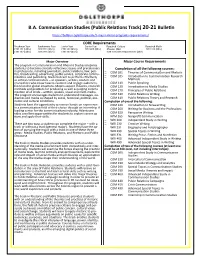

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

'Mediatization': Media Theory's Word of the Decade

’Mediatization’: Media Theory’s Word of the Decade John Corner To cite this version: John Corner. ’Mediatization’: Media Theory’s Word of the Decade. Media Theory, Media Theory, In press, Standard Issue, 2 (2), pp.79 - 90. hal-02047606 HAL Id: hal-02047606 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02047606 Submitted on 25 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Commentary ‘Mediatization’: Media Theory Vol. 2 | No. 2 | 79-90 © The Author(s) 2018 Media Theory’s Word CC-BY-NC-ND http://mediatheoryjournal.org/ of the Decade JOHN CORNER University of Leeds, UK Abstract This short commentary looks at aspects of the debate about the term „mediatization‟, paying particular attention to recent, cross-referring exchanges both in support of the concept and critical of it. In the context of its widespread use, it suggests that continuing questions need to be asked about the conceptual status of the term, the originality of the ideas it suggests and the kinds of empirical project to which it relates. Keywords mediatization, theory, politics, influence, institutional change No term has received more extensive attention in recent media theory than „mediatization‟. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

Growth and Dynamics of Maturing New Media Companies Growth and Dynamics of Maturing New Media Companies Growth and Dynamics Of

CINZIA DAL ZOTTO CINZIA DAL CINZIA DAL ZOTTO (ed.) CINZIA DAL ZOTTO (ed.) (ed.) Growth and Dynamics of Maturing New Media Companies Media Companies and Dynamics of Maturing New Growth Growth and Dynamics of Companies that were called “new media” fi rms a decade ago are now maturing and playing increasingly competitive roles in the media landscape and compre- Maturing New Media hension of the uses and opportunities presented by these technologies have evol- ved along with the fi rms. The changes resulting from the introduction of the technologies, and their uses by media and communication enterprises, today Companies present a host of realistic opportunities to both established and emergent fi rms. This book explores developments in the new media fi rms, their effects on traditional media fi rms, and emerging issues involving these media. It addresses Media Management and Transformation Centre issues of changes in the media environment, markets, products, and business practices and how media fi rms have adapted to those changes as the new techno- Jönköping International Business School logy fi rms have matured and their products have gained consumer acceptance. It explores organizational change in maturing new media companies, challenges of growth in these adolescent fi rms, changing leadership and managerial needs in growing and maturing fi rms, and internationalization of small and medium new media fi rms. The chapters in this volume reveal how they are now creating niches within media and communication activities that are providing them com- petitive spaces in which to further develop and succeed. The book is based on papers and discussions at the workshop, “The ‘New Economy’ Comes of Age: Growth and Dynamics of Maturing New Media Com- panies” sponsored by the Media Management and Transformation Centre of Jönköping International Business School, 12-13 November 2004. -

Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse

Nohrstedt, Stig A. "Mediatization as an Echo-Chamber for Xenophobic Discourses in the Threat Society: The Muhammad Cartoons in Denmark and Sweden." Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. Ed. Ruth Wodak, Majid KhosraviNik and Brigitte Mral. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. 309–320. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544940.ch-021>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 07:43 UTC. Copyright © Ruth Wodak, Majid KhosraviNik and Brigitte Mral and the contributors 2013. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 21 Mediatization as an Echo-Chamber for Xenophobic Discourses in the Threat Society: The Muhammad Cartoons in Denmark and Sweden Stig A. Nohrstedt Introduction This chapter reflects on the role of mainstream journalism in the proliferation of Islamophobia in late modern society, by analysing two cases where newspapers in Denmark and Sweden published cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. Both are instances of mediated perceptions of Muslims, symbolized by the Prophet, as a threat to freedom of speech, but in rather different ways. However, together they illustrate discursive processes and opinion-building strategies used by right-wing populism in which journalism becomes both amplifier and echo-chamber due to media logic. The first case, where the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten printed a series of Muhammad cartoons in 2005, has been intensively discussed both by journalists and media researchers (e.g. Eide et al. 2008, Sundström 2009). The second case, in 2007 where the Swedish newspaper Nerikes-Allehanda published a cartoon portraying Muhammad as a toy dog, has also been studied by media researchers (Camauër 2011, Camauër (ed.) forthcoming). -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Fifteen Pages That Shook the Field: Personal Influence, Edward Shils, and the Remembered History of Media Research

Personal Influence’s fifteen-page account of the development of mass communication research has had more influence on the field’s historical self-understand- ing than anything published before or since. According to Elihu Katz and Paul Lazarsfeld’s well-written, two- stage narrative, a loose and undisciplined body of pre- war thought had concluded naively that media are powerful—a myth punctured by the rigorous studies of Lazarsfeld and others, which showed time and again that media impact is in fact limited. This “powerful-to- limited-effects” storyline remains textbook boilerplate Fifteen Pages and literature review dogma fifty years later. This article traces the emergence of the Personal Influence synop- That Shook the sis, with special attention to (1) Lazarsfeld’s audience- dependent framing of key media research findings and (2) the surprisingly prominent role of Edward Shils in Field: Personal supplying key elements of the narrative. Influence, Keywords: Paul Lazarsfeld; Edward Shils; Elihu Katz; media research; history of social Edward Shils, science; disciplinary memory and the The bullet model or hypodermic model posits Remembered powerful, direct effects of the mass media. Survey studies of social influence conducted in History of Mass the late 1940s presented a very different model from that of a hypodermic needle in which a Communication multistep flow of media effects was evident. That is, most people receive much of their Research information and are influenced by media secondhand, through the personal influence of opinion leaders (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955). —Joseph Straubhaar and Robert LaRose (2006, 403) By JEFFERSON POOLEY Jefferson Pooley is assistant professor of media and communication at Muhlenberg College.