Emergency Department Diagnosis and Treatment of Anaphylaxis: a Practice Parameter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Between Anxiety, Syncope & Anaphylaxis

Differentiating between anxiety, syncope & anaphylaxis Dr. Réka Gustafson Medical Health Officer Vancouver Coastal Health Introduction Anaphylaxis is a rare but much feared side-effect of vaccination. Most vaccine providers will never see a case of true anaphylaxis due to vaccination, but need to be prepared to diagnose and respond to this medical emergency. Since anaphylaxis is so rare, most of us rely on guidelines to assist us in assessment and response. Due to the highly variable presentation, and absence of clinical trials, guidelines are by necessity often vague and very conservative. Guidelines are no substitute for good clinical judgment. Anaphylaxis Guidelines • “Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening IgE mediated allergic reaction” – How many people die or have died from anaphylaxis after immunization? Can we predict who is likely to die from anaphylaxis? • “Anaphylaxis is one of the rarer events reported in the post-marketing surveillance” – How rare? Will I or my colleagues ever see a case? • “Changes develop over several minutes” – What is “several”? 1, 2, 10, 20 minutes? • “Even when there are mild symptoms initially, there is a potential for progression to a severe and even irreversible outcome” – Do I park my clinical judgment at the door? What do I look for in my clinical assessment? • “Fatalities during anaphylaxis usually result from delayed administration of epinephrine and from severe cardiac and respiratory complications. “ – What is delayed? How much time do I have? What is anaphylaxis? •an acute, potentially -

(Loxapine) REMS

Current as of 6/1/2013.® This document may not be part of the latest approved REMS. Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2091 Stierlin Court, Mountain View, CA 94043 IMPORTANT DRUG WARNING Risk of bronchospasm with ADASUVE™ (loxapine) inhalation powder ADASUVE™ available only in enrolled healthcare facilities, under an FDA-required REMS Program Dear Healthcare Professional: This letter contains important safety information for ADASUVE™ (loxapine) Inhalation Powder. ADASUVE is a drug-device combination product that delivers the antipsychotic, loxapine, by oral inhalation. ADASUVE has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder in adults. FDA has determined that a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is necessary to ensure that the benefits of treatment outweigh the risk of bronchospasm in patients treated with ADASUVE. ADASUVE is not available in an outpatient setting. If you are an outpatient provider, you are receiving this letter because ADASUVE may be, or may have been, administered to one of your patients in an enrolled healthcare facility. Enrolled healthcare facilities, such as an acute care or inpatient setting, must have immediate on-site access to equipment and personnel trained to manage acute bronchospasm, including advanced airway management, eg, intubation and mechanical ventilation. (See below for more facility enrollment requirements.) It is important that anyone caring for patients treated with ADASUVE be aware of the risk of bronchospasm after administration. This letter does not contain a complete list of all the risks associated with ADASUVE. Reference ID:Please 3235446 see the enclosed full prescribing information for more information. -

Inhaled Loxapine Monograph

Inhaled Loxapine Monograph Inhaled Loxapine (ADASUVE) National Drug Monograph February 2015 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a comprehensive drug review for making formulary decisions. Updates will be made when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. FDA Approval Information Description/Mechanism of Inhaled loxapine is a typical antipsychotic used in the treatment of acute Action agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder in adults. Loxapine’s mechanism of action for reducing agitation in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder is unknown. Its effects are thought to be mediated through blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors as well as some activity at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Indication(s) Under Review in Inhaled loxapine is a typical antipsychotic indicated for the acute treatment of this document (may include agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder in adults. off label) Off-label use Agitation related to any other cause not due to schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Dosage Form(s) Under 10mg oral inhalation using a new STACCATO inhaler device. Review REMS REMS No REMS Post-marketing Study Required See Other Considerations for additional REMS information Pregnancy Rating C Executive Summary Efficacy Inhaled loxapine was superior to placebo in reducing acute agitation at 2 hours post dose measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Excited Component (PEC) in patients with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia. -

Beta Adrenergic Agents

Beta2 Adrenergic Agents –Long Acting Review 04/10/2008 Copyright © 2007 - 2008 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Comments and suggestions may be sent to [email protected]. -

BREATHLESSNESS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Dyspnoea, Also

EMERGENCY MEDICINE – WHAT THE FAMILY PHYSICIAN CAN TREAT UNIT NO. 4 BREATHLESSNESS In one study of 85 patients presenting to a pulmonary unit Psychiatric conditions appropriate context of the history, physical examination, and ischaemia. Serial measurements of cardiac biomarkers are inhaler (MDI). In severe asthma, patients should be transferred breathlessness. In such cases, it is prudent to start therapies for with a complaint of chronic dyspnoea, the initial impression Psychogenic causes for acute dyspnoea is a diagnosis of the consideration of dierential diagnosis. Random testing necessary as initial results can often be normal. to ED for further treatment with nebulised ipratropium multiple conditions in the initial resuscitative phase. For Dr Pothiawala Sohil of the aetiology of dyspnoea based upon the patient history exclusion, and organic causes must be ruled out rst before without a clear dierential diagnosis will delay appropriate bromide, intravenous magnesium, ketamine, IM adrenaline, example, for a patient with a past medical history of COPD and alone was correct in only 66 percent of cases.4 us, a considering this diagnosis (e.g., panic attack).5 management. e use of dyspnoea biomarker panels does not Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) intubation, and inhalational anaesthesia as needed. congestive cardiac failure, the initial management of sudden systematic approach, comprising of adequate history and appear to improve accuracy beyond clinical assessment and is is used to diagnose heart failure, but it can also be elevated onset of dyspnoea may include therapies directed at both these ABSTRACT diagnostic studies, and provide recommendations for initial physical examination, followed by appropriate investigations focused testing.6, 7 in uid overload secondary to renal failure. -

Adasuve, INN-Loxapine

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT ADASUVE 4.5 mg inhalation powder, pre-dispensed 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each single-dose inhaler contains 5 mg loxapine and delivers 4.5 mg loxapine. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Inhalation powder, pre-dispensed (inhalation powder). White device with a mouthpiece on one end and a pull-tab protruding from the other end. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications ADASUVE is indicated for the rapid control of mild-to-moderate agitation in adult patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Patients should receive regular treatment immediately after control of acute agitation symptoms. 4.2 Posology and method of administration ADASUVE should only be administered in a hospital-setting under the supervision of a healthcare professional. Short-acting beta-agonist bronchodilator treatment should be available for treatment of possible severe respiratory side-effects (bronchospasm). Posology The recommended initial dose of ADASUVE is 9.1 mg. A second dose can be given after 2 hours, if necessary. No more than two doses should be administered. A lower dose of 4.5 mg may be given if the 9.1 mg dose was not previously tolerated by the patient or if the physician decides a lower dose is more appropriate. Patient should be observed during the first hour after each dose for signs and symptoms of bronchospasm. Elderly The safety and efficacy of ADASUVE in patients older than 65 years of age have not been established. No data are available. Renal and/or hepatic impairment ADASUVE has not been studied in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. -

These Highlights Do Not Include All the Information Needed to Use SPIRIVA HANDIHALER Safely and Effectively

SPIRIVA HANDIHALER- tiotropium bromide capsule A-S Medication Solutions ---------- HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION These highlights do not include all the information needed to use SPIRIVA HANDIHALER safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for SPIRIVA HANDIHALER. SPIRIVA® HANDIHALER® (tiotropium bromide inhalation powder), for oral inhalation use Initial U.S. Approval: 2004 INDICATIONS AND USAGE SPIRIVA HANDIHALER is an anticholinergic indicated for the long-term, once-daily, maintenance treatment of bronchospasm associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and for reducing COPD exacerbations (1) DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION For oral inhalation only. DO NOT swallow SPIRIVA capsules. Only use SPIRIVA capsules with the HANDIHALER device (2) Two inhalations of the powder contents of a single SPIRIVA capsule (18 mcg) once daily (2) DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS Inhalation powder: SPIRIVA capsules contain 18 mcg tiotropium powder for use with HANDIHALER device (3) CONTRAINDICATIONS Hypersensitivity to tiotropium, ipratropium, or any components of SPIRIVA capsules (4) WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS Not for acute use: Not a rescue medication (5.1) Immediate hypersensitivity reactions: Discontinue SPIRIVA HANDIHALER at once and consider alternatives if immediate hypersensitivity reactions, including angioedema, urticaria, rash, bronchospasm, or anaphylaxis, occur. Use with caution in patients with severe hypersensitivity to milk proteins. (5.2) Paradoxical bronchospasm: Discontinue SPIRIVA HANDIHALER and consider other treatments if paradoxical bronchospasm occurs (5.3) Worsening of narrow-angle glaucoma may occur. Use with caution in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma and instruct patients to consult a physician immediately if this occurs. (5.4) Worsening of urinary retention may occur. Use with caution in patients with prostatic hyperplasia or bladder-neck obstruction and instruct patients to consult a physician immediately if this occurs. -

Ipratropium Bromide Solution Cobalt Laboratories, Inc.

IPRATROPIUM BROMIDE- ipratropium bromide solution Cobalt Laboratories, Inc. ---------- Prescribing Information Rx Only DESCRIPTION The active ingredient in Ipratropium Bromide Inhalation Solution is ipratropium bromide monohydrate. It is an anticholinergic bronchodilator chemically described as 8-azoniabicyolo[3.2.1]-octane, 3-(3- hydroxy-1-oxo-2-phenyl-propoxy)-8 methyl-8-(1-methylethyl)-, bromide, monohydrate (endo, syn)-,(±)- ; a synthetic quaternary ammonium compound, chemically related to atropine. Ipratropium bromide is a white crystalline substance, freely soluble in water and lower alcohols. It is a quaternary ammonium compound and thus exists in an ionized state in aqueous solutions. It is relatively insoluble in non-polar media. Ipratropium Bromide Inhalation Solution is administered by oral inhalation with the aid of a nebulizer. It contains ipratropium bromide 0.02% (anhydrous basis) in a sterile, isotonic saline solution, pH-adjusted to 3.4 (3 to 4) with hydrochloric acid. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Ipratropium bromide is an anticholinergic (parasympatholytic) agent that, based on animal studies, appears to inhibit vagally mediated reflexes by antagonizing the action of acetylcholine, the transmitter agent released from the vagus nerve. Anticholinergics prevent the increases in intracellular concentration of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP) that are caused by interaction of acetylcholine with the muscarinic receptor on bronchial smooth muscle. The bronchodilation following inhalation of ipratropium bromide is primarily a local, site-specific effect, not a systemic one. Much of an administered dose is swallowed but not absorbed, as shown by fecal excretion studies. Following nebulization of a 2 mg dose, a mean 7% of the dose was absorbed into the systemic circulation either from the surface of the lung or from the gastrointestinal tract. -

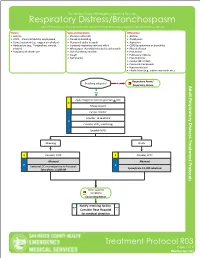

Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm for COPD/Asthma Exacerbations and Any Bronchospasms/Wheezing Not from Pulmonary Edema

San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm For COPD/asthma exacerbations and any bronchospasms/wheezing not from pulmonary edema History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Asthma • Shortness of breath • Asthma • COPD – chronic bronchitis, emphysema • Pursed lip breathing • Anaphylaxis • Home treatment (e.g., oxygen or nebulizer) • Decreased ability to speak • Aspiration • Medications (e.g., Theophylline, steroids, • Increased respiratory rate and effort • COPD (emphysema or bronchitis) inhalers) • Wheezing or rhonchi/diminished breath sounds • Pleural effusion • Frequency of inhaler use • Use of accessory muscles • Pneumonia • Cough • Pulmonary embolus • Tachycardia • Pneumothorax • Cardiac (MI or CHF) • Pericardial tamponade • Hyperventilation • Inhaled toxin (e.g., carbon monoxide, etc.) Respiratory Arrest/ Breathing adequate? No Respiratory Failure Yes Apply Oxygen to maintain goal SpO2 > 92% E Airway support Cardiac monitor Consider, 12-Lead ECG P Consider, EtCO2 monitoring Establish IV/IO Wheezing Stridor E Consider, CPAP E Consider, CPAP Albuterol Albuterol P P Decrease LOC or unresponsive to Albuterol, Epinephrine 1:1,000 nebulized Epinephrine 1:1,000 IM Other systemic symptoms Exit to Anaphylaxis Notify receiving facility. Consider Base Hospital for medical direction Treatment Protocol R03 Page 1 of 2 Effective NovemberEffective April 2018 2020 San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Respiratory Distress/Bronchospasm For COPD/asthma exacerbations and any bronchospasms/wheezing not from pulmonary edema Pearls • A silent chest in respiratory distress is a pre-respiratory arrest sign. • Patients receiving epinephrine should receive a 12-Lead ECG at some point in their care in the prehospital setting, but this should NOT delay the administration of Epinephrine. • Pulse oximetry monitoring is required for all respiratory patients. Treatment Protocol R03 Page 2 of 2 Effective EffectiveNovember April 2018 2020. -

Reversible Bronchospasm with the Cardio-Selective Beta-Blocker Celiprolol in a Non-Asthmatic Subject

Respiratory Medicine CME (2009) 2, 141e143 CASE REPORT Reversible bronchospasm with the cardio-selective beta-blocker celiprolol in a non-asthmatic subject Rubab Ahmed, Howard M. Branley* Department of Respiratory Medicine, The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust, Magdala Avenue, London N19 5NF, UK Received 5 October 2008; accepted 16 October 2008 KEYWORDS Summary Selective beta blockers; Beta (b)-blockers are widely used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease but are well Celiprolol; recognised for causing bronchoconstriction in asthmatic subjects. The third-generation car- Bronchoconstriction; dio-selective b-blocker celiprolol is a selective b1-adrenergic blocking agent with b2-agonist Asthma properties and would therefore be a preferred b-blocker if an asthmatic subject required treat- ment with b-blockers for cardiovascular disease. We present the case of a 79-year-old man with ischaemic heart disease and hypertension but no preceding respiratory disease who developed significant bronchoconstriction on celiprolol, which resolved completely on drug cessation alone with no relapse of respiratory symptoms two years after cessation of treatment. ª 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Introduction relatively cardio-selective but are not cardio-specific. Cel- iprolol additionally possesses vasodilator properties b-blockers are widely used in the treatment of cardiovas- through blockade of vascular alpha-adrenoceptors. Celiprolol has been widely reported as being non-bron- cular disease, including hypertension, angina, myocardial 1,2 b choconstrictive -

Patient's Instructions for Use Ipratropium Bromide Inhalation

significant improvement in subjective symptom scores nor in quality of life scores over the 12-week duration of study. Patient’s Instructions for Use Additional controlled 12-week studies were conducted to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of ipratropium bromide inhalation solution administered concomitantly Ipratropium Bromide with the beta adrenergic bronchodilator solutions metaproterenol and albuterol compared with the Inhalation Solution, 0.02% administration of each of the beta agonists alone. Combined therapy produced significant additional Read complete instructions carefully before improvement in FEV1 and FVC. On combined therapy, using. the median duration of 15% improvement in FEV1 was 5- Ipratropium Bromide 7 hours, compared with 3-4 hours in patients receiving a beta agonist alone. 1. Twist open the top of one unit dose vial and Inhalation Solution, 0.02% INDICATIONS AND USAGE Ipratropium bromide squeeze the contents into the nebulizer reservoir inhalation solution administered either alone or with other (Figure 1). Rx only bronchodilators, especially beta adrenergics, is indicated as a bronchodilator for maintenance treatment of Prescribing Information bronchospasm associated with chronic obstructive DESCRIPTION The active ingredient in ipratropium pulmonary disease, including chronic bronchitis and bromide inhalation solution is ipratropium bromide emphysema. monohydrate. It is an anticholinergic bronchodilator CONTRAINDICATIONS Ipratropium bromide inhalation chemically described as 8-azoniabicyclo[3.2.1]-octane, solution is contraindicated in known or suspected cases 3-(3-hydroxy-1-oxo-2-phenylpropoxy)-8-methyl-8-(1- of hypersensitivity to ipratropium bromide, or to atropine methylethyl)-, bromide, monohydrate (endo, syn)-,(±)-; and its derivatives. a synthetic quaternary ammonium compound, WARNINGS The use of ipratropium bromide inhalation chemically related to atropine. -

Descriptors of Dyspnea in Obstructive Lung Diseases Descrittori Di Dispnea Nelle Patologie Ostruttive Delle Vie Aeree

Multidisciplinary Focus on: Dyspnea edited by / a cura di Giorgio Scano Descriptors of dyspnea in obstructive lung diseases Descrittori di dispnea nelle patologie ostruttive delle vie aeree Sabina A. Antoniu University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Gr. T. Popa” Iasi, Department of Internal Medicine II - Pulmonary Disease, Pulmonary Disease University Hospital ABSTRACT descrittori) con i meccanismi fisiologici e fisiopatologici sot- In obstructive lung diseases such as asthma and COPD dysp- tostanti. Questi studi sono stati effettuati nell’asma piutto- nea is a common respiratory symptom with different charac- sto che nella BPCO ed i descrittori di dispnea sono stati ri- teristics given the different pathogenic mechanisms: in COPD scontrati utili per identificare i pazienti con asma in pericolo initially it can occur during exertion but then it increases pro- di vita. Tuttavia studi ulteriori sono necessari per esplorare ul- gressively along with the airflow obstruction, whereas in teriormente questi descrittori e la loro utilità clinica. In que- asthma it occurs episodically and is caused by transient bron- sta rassegna vengono analizzati i meccanismi della dispnea choconstriction. nei vari sottogruppi di patologie respiratorie di tipo ostrutti- The language of dyspnea includes a large range of clinical vo, come pure i descrittori di dispnea e la loro utilità nella pra- descriptors which have been evaluated for their correlation (of tica clinica. one or several descriptors) with underlying physiologic/phys- iopathologic mechanisms. These studies were done in asthma Parole chiave: Descrittori, dispnea, patologie ostruttive respi- rather than in COPD, and dyspnea descriptors were found to be ratorie, test da sforzo. useful in identifying patients with life-threatening asthma.