Focus Report for the Proposed Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TABLE of CONTENTS 1.0 Background

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Background ....................................................................... 1 1.1 The Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Study Process .............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Early Settlement ................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Community Involvement and Associations ...................................................... 4 1.5 Area Demographics ............................................................................................ 6 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 Cohort Model .............................................................................................................................. 6 Population by Generation ........................................................................................................... 7 Income Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 7 Family Size and Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 Household Characteristics by Condition and Period of -

Chebucto Peninsula) Municipal Planning Strategy and Land Use By-Law for 90 Club Road and a Portion of PID 40072530, Harrietsfield

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 15.5.2 Halifax Regional Council April 30, 2019 TO: Mayor Savage Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: For Councillor Stephen D. Adams, Chair, Halifax and West Community Council DATE: April 10, 2019 SUBJECT: Case 20160: Amendments to the Planning District 5 (Chebucto Peninsula) Municipal Planning Strategy and Land Use By-law for 90 Club Road and a portion of PID 40072530, Harrietsfield ORIGIN April 9, 2019 meeting of Halifax and West Community Council, Item 13.1.2. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY HRM Charter, Part 1, Clause 25(c) – “The powers and duties of a Community Council include recommending to the Council appropriate by-laws, regulations, controls and development standards for the community.” RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Give first reading to consider the proposed amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy and Land Use By-law for Planning District 5 (Chebucto Peninsula), as set out in Attachments A and B of the staff report dated January 8, 2019, to enable the conversion of a former satellite receiving station to a commercial use at 90 Club Road, Harrietsfield and to permit residential uses on the remainder of the property and a portion of PID 40072530, Harrietsfield and schedule a joint public hearing; and 2. Adopt the proposed amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy and Land Use By-law for Planning District 5 (Chebucto Peninsula), as set out in Attachments A and B of the staff report dated January 8, 2019. Case 20160 Council Report - 2 - April 30, 2019 BACKGROUND At their April 9, 2019 meeting, Halifax and West Community Council considered the staff report dated January 8, 2019 regarding Case 20160: Amendments to the Planning District 5 (Chebucto Peninsula) Municipal Planning Strategy and Land Use By-law for 90 Club Road and a portion of PID 40072530, Harrietsfield. -

Municipal Planning Strategy

MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) THIS COPY IS A REPRINT OF THE MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY WITH AMENDMENTS TO MARCH 26, 2016 MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY FOR PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) THIS IS TO CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Municipal Planning Strategy for Planning District 5 which was passed by a majority vote of the former Halifax County Municipality at a duly called meeting held on the 5th day of December, 1994, and approved with amendments by the Minister of Municipal Affairs on the 9th day of February, 1995, which includes all amendments thereto which have been adopted by the Halifax Regional Municipality and are in effect as of the 26th day of March, 2016. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the seal of Halifax County Municipality this day of ___________________________, 20___. Municipal Clerk MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY FOR PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) FEBRUARY 1995 This document has been prepared for convenience only and incorporates amendments made by the Council of Halifax County Municipality on the 5th day of December, 1994 and includes the Ministerial modifications which accompanied the approval of the Minister of Municipal Affairs on the 9th day of February, 1995. Amendments made after this approval date may not necessarily be included and for accurate reference, recourse should be made to the original documents. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy OCTOBER 2014 Regional Municipal Planning Strategy I HEREBY CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Regional Municipal Planning Strategy which was duly passed by a majority vote of the whole Regional Council of Halifax Regional Municipality held on the 25th day of June, 2014, and approved by the Minister of Municipal Affairs on October 18, 2014, which includes all amendments thereto which have been adopted by the Halifax Regional Municipality and are in effect as of the 3rd day of November, 2018. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the corporate seal of the Municipality this _____ day of ____________________, 20___. __________________________________ Municipal Clerk 2 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 8 1.1 THE FIRST FIVE YEAR PLAN REVIEW ......................................................................................................... 8 1.2 VISION AND PRINCIPLES .............................................................................................................................. 10 1.3 OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.4 HRM: FROM PAST TO PRESENT .................................................................................................................. 14 1.4.1 Settlement in HRM ................................................................................................................................. -

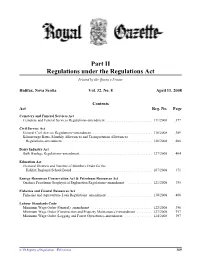

NS Royal Gazette Part II

Part II Regulations under the Regulations Act Printed by the Queen’s Printer Halifax, Nova Scotia Vol. 32, No. 8 April 11, 2008 Contents Act Reg. No. Page Cemetery and Funeral Services Act Cemetery and Funeral Services Regulations–amendment .......................... 111/2008 377 Civil Service Act General Civil Service Regulations–amendment.................................. 116/2008 389 Kilometrage Rates, Monthly Allowances and Transportation Allowances Regulations–amendment.................................................. 128/2008 406 Dairy Industry Act Bulk Haulage Regulations–amendment........................................ 127/2008 404 Education Act Electoral Districts and Number of Members Order for the Halifax Regional School Board ............................................ 107/2008 371 Energy Resources Conservation Act & Petroleum Resources Act Onshore Petroleum Geophysical Exploration Regulations–amendment ............... 121/2008 395 Fisheries and Coastal Resources Act Fisheries and Aquaculture Loan Regulations–amendment ......................... 130/2008 408 Labour Standards Code Minimum Wage Order (General)–amendment .................................. 122/2008 396 Minimum Wage Order (Construction and Property Maintenance)–amendment......... 123/2008 397 Minimum Wage Order (Logging and Forest Operations)–amendment ................ 124/2008 397 © NS Registry of Regulations. Web version. 369 Table of Contents (cont.) Royal Gazette Part II - Regulations Vol. 32, No. 8 Motor Vehicle Act Classification of Drivers’ Licenses Regulations–amendment -

David Patriquin to Regional Council Sep 24, 2019 Re: Case 21956, Proposed Amendment to the Regional Plan’S Conservation Design Development Agreement Policies

David Patriquin to Regional Council Sep 24, 2019 Re: Case 21956, proposed amendment to the Regional Plan’s conservation design development agreement policies I am a retired member of the biology Dept at Dal I want to talk in particular about the Chebucto Peninsula and its conectivoty to the broader mainland *Over the past approx. 15 years, I have volunteered) with several organizations to document ecological values of various openspaces on the Chebucto Peninusla for conservation purposes, as well as on management of The Bluff Trail. Currently, I am working with the Sandy Lake Conservation Association and the related Alliance to document ecological values of the broad sweep of currently undeveloped, mostly forested landscape that surrounds Sandy Lake and extends from Hammonds Plains Road to the Sackville River; also to document limnological characteristics of the Sandy Lake to Sackville River watercourse. This is an important corridor area between open spaces on the Chebucto Peninsula and those on the broader NS mainland REMARKABLY, Approx. 30% of the Chebucto Peninsula is now in Parks and Protected Areas (PPA), and another 12% still remains as undeveloped Crown land or HRM land, making the Chebucto Peninsula a significant conservation area - for comparison, 12.4% of the land area of NS is in PPA, ~15% for of Halifax Co./HRM). As recognized and highlighted in the HGNP and we need to create or maintain ecological connectivity in the form of corridors between the various open spaces and across the boundaries of HRM. Because there is so much protected land within the Cheb Peninsula, connectivity within the peninsula is not that big an issue, but there are still some critical corridors to be protected within the Peninsula as Id’d the HGNP See Page 49 and 50 of the GNPlan” What’s especially dicey is the connectivity across the neck of the Peninsula onto the NS mainland Highway 103, and Hammonds Plains Road cutting across it, and with significant residential development in the neck area. -

Chebucto Terence Bay Wind Farm

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

The Canadian Maritimes: Images and Encounters. Pathways in Geography Series Resource Publication, Title No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 383 625 SO 024 986 AUTHOR Ennals, Peter, Ed. TITLE The Canadian Maritimes: Images and Encounters. Pathways in Geography Series Resource Publication, Title No. 6. INSTITUTION National Council for Geographic Education. REPORT NO ISBN-0-962737-9-8-4 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 68p.; Paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the National Council for Geographic Education (Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, August 3-7, 1993). AVAILABLE FROMNational Council for Geographic Education, 16-A Leonard Hall, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA 15705 ($5). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Guides Non- Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Area Studies; *Canadian Studies; Cross Cultural Studies; Culture; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; Geographic Location; *Geographic Regions; *Geography; Higher Education; Multicultural Education; *North American Culture; North American History; North Americans IDENTIFIERS *Canada (Maritime Provinces) ABSTRACT This guide covers the Canadian Maritime provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. The first in a series prepared for geographers and those interested in travel, this guide is written by local geographers or others with special expertise on the area and provides insights and a feeling for place that textbooks often miss. This guide introduces a region outside the geographical experience of most people in the United States and of many Canadians. The complexities, joys, and challenges of this multicultural region are -

Landscapes of the Five Bridge Lakes Wilderness Area: a Natural History

Retrieved from DalSpace, the institutional repository of Dalhousie University https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/handle/10222/79576 Version: Post-print Publisher’s versionPatriquin, David. 2010. Landscapes of the Five Bridge Lakes Wilderness Area: A Natural History. Keynote presentation to AGM of Woodens River Watershed Environmental Organization, Feb. 17, 2010. 2 3 •5 •7 UIV\,oIscet-pes oftVte • •10 11 F~ve f;y~oIge Let~es 12 ,.13 W~LoIeYv\'ess ,.15 Ayeet 17 , ,. A N C1tuyCI L f-tL.stOYl::J 2D 21 22 23 2. 25 2. 27 2. 2. 30 31 32 blufftrail.cajwrweo.ca fivebrldgestrust.ca 1 When we enter the Five Bridge Lakes Wilderness Area (FBLWA) , perhaps via the Bluff Trail or the Old St. Margarets's Bay Road, or paddling a lake, we encounter a varied landscape of lakes, streams, rivers, drumlins, erratics, mixed, deciduous and coniferous forest, bushland, rocky barrens, swamps, fens and bogs. The description of 3 this landscape and the interpretation of "how it came to be" is the business of "natural history". This set of web pages provides a brief •5 overview of the natural history of landscapes of the FBLWA. •7 The Five Bridge Lakes Wilderness Area lies about 20 kilometers west of downtown Halifax, Nova Scotia. It encompasses almost 10,000 ,• hectares of Crown land located in the centre of the Chebucto ,. Peninsula between highways 103 and 333. Efforts have been made 11 since the mid-1990's to protect parts or all of the crown lands in the 12 FBLWA. These efforts came to fruition in October of 2009, when the 13 Minister of Environment for Nova Scotia declared the Five Bridge ,. -

STATUS REPORT on the Eastern Moose (Alces Alces Americana Clinton) in Mainland Nova Scotia

STATUS REPORT on The Eastern Moose (Alces alces americana Clinton) in Mainland Nova Scotia by Gerry Parker 23 Marshview Drive, Sackville, New Brunswick. E4L 3B2 [email protected] (June 6, 2003) 2 TECHNICAL SUMMARY DISTRIBUTION Extent of occurrence: Mainland Nova Scotia; ~ 55,000 km2 Area of Occupancy: Fragmented; ~ six foci of distribution of ~ 10,000 km2 POPULATION INFORMATION Total number of individuals in the mainland Nova Scotia population: Uncertain, but approximately 1,000 to 1,200. Number of mature individuals in the mainland Nova Scotia population (effective population size): Perhaps 85% of estimated population, or 850 to 1,000individuals. Generation time: Average life expectancy of 8-10 years. Population trend: __X____ declining _____increasing _____ stable _____unknown Rate of population decline: ~ 20% in 30 years Number of sub-populations: Possibly 3: northeastern; southwestern; eastern shore. Is the population fragmented? Yes. number of individuals in each subpopulation: see map in Figure 1. number of historic sites from which species has been extirpitated: All of mainland except where noted above. Does the species undergo fluctuations? Irregular long-term trends. THREATS The moose of mainland Nova Scotia are fully protected from legal hunting but are subjected to poaching of an uncertain extent. Increased incursion into wilderness moose habitat by forestry roads raises the threat of disturbance from humans and illegal kill. Moose are also subject to mortality from the parasite Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, a brainworm common to white-tailed deer, and are often restricted to areas of deer absence or scarcity. Dead or dying moose have been necropsied with symptoms of an unidentified viral infection – the real threat of this possible pathogen is yet to be determined. -

TESS Resource Directory YWCA Halifax

TESS Directory We would like to thank the Canadian Women’s Foundation and NSACSW for funding the TESS partnership from 2016-2021 Nova Scotia Advisory Council on The Status of Women [email protected] @TESSNovaScotia Back cover and endpaper artwork contributed by youth connected through the POSSE Program HALIFAX LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Pjila’si (Welcome) We begin this directory by acknowledging that the Trafficking & Exploitation Services System (TESS) partnership operates in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people. Of particular importance, we recognize colonization as gendered oppression and its relation to the ongoing experiences of Indigenous people with sexual violence and exploitation, most especially Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). In its structure and activities, TESS aims to honour several Calls for Justice stemming from the National Inquiry into MMIWG, including: • denouncing and speaking out against violence against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people; • breaking down stereotypes and busting myths that hypersexualize and demean Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people; • providing and promoting ongoing awareness and training on the issue of grooming for exploitation and sexual exploitation; [email protected] [email protected] 4 @TESSNovaScotia @TESSNovaScotia 5 • developing specialized Indigenous/community-led responses to the issue of human trafficking and sexual exploitation; • supporting programs and services for Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people in the sex industry to promote their safety and security, including delivering these services in partnership with people who have lived experience in the sex industry; and • developing prevention initiatives in the areas of health and community awareness related to sexual trafficking awareness and no-barrier exiting. -

Model for Plausibility of Land Availability for Wine Grape Growing

Model for Plausibility of Land Available for Wine Grape Growing based on Land Use Policy, Planning, and Regulation and Agricultural Land Conversion over Time Prepared for the AgriRisk project, Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture Prepared by the School of Planning, Dalhousie University March 31, 2018 Research team: Dr. Eric Rapaport Dr. Patricia Manuel Yvonne Reeves, Research Assistant Katie Sonier, Research Assistant (Citation: Rapaport, E., Manuel, P., Reeves, Y., and Sonier, E. (2018, March, 28). Policy, Planning, and Regulation and Agricultural Land Conversion over Time Report. School of Planning, Dalhouise University., pp. 1-81.) Risk Proofing Nova Scotia Agriculture: A Risk Assessment System Pilot (AgriRisk) Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture would like to recognize the collaborative relationships that exist among Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the Nova Scotia Departments of Agriculture and Environment. Copyright 2018 ©. No license is granted in this publication and all intellectual property rights, including copyright, are expressly reserved. This publication shall not be copied except for personal, non- commercial use. Any copy must clearly display this copyright. While the information in this publication is believed to be reliable when created, accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Use the publication at your own risk. Any representation, warranty, guarantee or conditions of any kind, whether express or implied with respect to the publication is hereby disclaimed. The authors and publishers of this report are not responsible in any manner for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages or any other damages of any kind howsoever caused arising from the use of this Report. i Summary This model and analysis were developed to inform future land availability for crop agricultural use, including viticulture (grape growing).