Henry Watterson--A Study of Selected Speeches on Reconciliation in the Post-Bellum Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Books List October-December 2011

New Books List October-December 2011 This catalogue of the Shakespeare First Folio (1623) is the result of two decades of research during which 232 surviving copies of this immeasurably important book were located – a remarkable 72 more than were recorded in the previous census over a century ago – and examined in situ, creating an essential reference work. ෮ Internationally renowned authors Eric Rasmussen, co-editor of the RSC Shakespeare series and Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, USA; Anthony James West, Shakespeare scholar, focused on the history of the First Folio since it left the press. ෮ Full bibliographic descriptions of each extant copy, including detailed accounts of press variants, watermarks, damage or repair and provenance ෮ Fascinating stories about previous owners and incidents ෮ Striking Illustrations in a colour plate section ෮ User’s Guide and Indices for easy cross referencing ෮ Hugely significant resource for researchers into the history of the book, as well as auction houses, book collectors, curators and specialist book dealers November 2011 | Hardback | 978-0-230-51765-3 | £225.00 For more information, please visit: www.palgrave.com/reference Order securely online at www.palgrave.com or telephone +44 (0)1256 302866 fax + 44(0)1256 330688 email [email protected] Jellybeans © Andrew Johnson/istock.com New Books List October-December 2011 KEY TO SYMBOLS Title is, or New Title available Web resource as an ebook Textbook comes with, a available CD-ROM/DVD Contents Language and Linguistics 68 Anthropology -

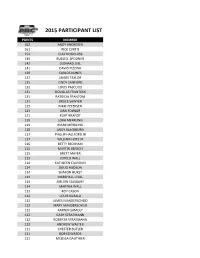

2015 Abcs Membersht.Csv

2015 PARTICIPANT LIST POINTS MEMBER 162 ANDY ANDRESEN 161 RICK CURTIS 152 CLAY DOUGLASS 145 RUSSELL SPOONER 142 LEONARD DILL 141 DAVID PIZZINO 139 CARLOS NUNES 137 JAMESTAYLOR 135 CINDY SANFORD 132 LOUIS PASCUCCI 131 DOUGLAS FRANTOM 131 PATRICIA FRANTOM 131 BRUCE SAWYER 125 NIKKI PETERSEN 123 DANFOWLER 121 KURT BRANDT 119 LORA MERKLING 119 MARK MERKLING 118 ANDY BLACKBURN 117 PHILLIP HALLFORD JR 117 WILLIAM HOTZ JR 116 BETTY BECKHAM 115 MARTIN BENSCH 115 BRETT MAYER 115 JEROLD WALL 114 KATHLEEN CALHOUN 114 DOUG HUDSON 114 SHARON HURST 114 MARSHALL LYALL 114 MELVIN SALSBURY 114 MARTHA WALL 113 ROY CASON 112 LOUIS KUBALA 112 JAMES MANDERSCHEID 112 MARY MANDERSCHEID 112 KAYREN SAMOLY 112 GARY STRATMANN 112 ROBERTA STRATMANN 112 ANDREW WALTER 111 CHESTER BUTLER 111 BOB EDWARDS 111 MELISSA GAUTHIER 111 LARRY LANGLINAIS 111 FREDERICK MCKAY 111 JAMES PIRTLE 111 THELMA PIRTLE 110 JOHN BRATSCHUN 110 NORMA EDWARDS 110 JEFF MCCLAIN 110 SANDRA MCCLAIN 110 MICHAEL PRITCHETT 110 CAROL TIMMONS 110 ROBERT TIMMONS 109 ERNEST STAPLES SR 108 BYRON CONSTANCE 108 ALFRED RATHBUN 107 WILLIAM BUSHALL JR 107 A CALVERT 107 JOHNKIME 107 KELLIE SALSBURY 106 MICHAEL ISEMAN 106 MONAOLSEN 106 THOMASOLSEN 106 SAMUEL STONE 106 JOHNTOOLE 105 VICTOR PONTE 104 PAUL CIPAR 104 DAVID THOMPSON 103 JOHN MCFADDEN 103 BENJAMIN PHILHOWER 103 SHERI PHILHOWER 103 BILL STOCK JR 103 MARTHA STOCK 102 GARY DYER 101 EDWARD GARBIN 101 TEDLAWSON 101 ROY STEPHENS JR 101 CLINT STOTT 100 JACK HARTLEY 100 PETER HULL 100 AARON KONECKY 100 DONNA LANDERS 100 GLEN LANDERS 100 DONSEPANSKI 99 CATHEY -

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon June 1928

W^^www^ @ �l^lt] [*) l^^^iW^W^W^ DIAMOND f^ . of . ^ Psi Upsilcsn �a? June 1928 Volume XIV Number Four i Ti?'zi?'ii?'^^^^l [f] IT] [T] ? BIjEII^ |Ny%^^ii<>'-tifW THE DIAMOND OF PSI UPSILON Official Publication of Psi Upsilon Fraternity Published in November, January, March and June, by The Diamond of Psi Upsilon, a corporation not for pecuniary profit, organized under the laws of Illinois An Open Forum for the Free Discussion of Fraternity Matters Volume XIV JUNE, 1928 Numbee 4 BOARD OP EDITORS Mask Bowman ....... Delta Delta '20 R. BouRKE Corcoran Omega '15 Ralph C. Guenther Tau'26 Kenneth Laied Omega '25 George W. Ross, Jb Phi '26 ALUMNI ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE DIAMOND Henet Johnson Fisher Beta '96 Herbert S. Houston Omega '88 Edward Hungeefoed Pi '99 Julian S. Mason . .... Beta '98 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL COMMITTEE ON THE DIAMOND Walter T. Collins Iota '03 R. BouRKE Corcoran Omega '15 Herbert S. Houston Omega '88 LIFE SUBSCRIPTION TEN DOLLARS ONE DOLLAR THE YEAR BY SUBSCRIPTION SINGLE COPIES FIFTY CENTS MdresB all communications to the Board of Editors, Room 500, 30 N. Dearborn St., TABLE of CONTENTS The 1928 Convention 209 Notes of the Convention 211 The Alumni Conference 212 The Convention Banquet 216 A Scholarship Prize of $500 230 Delta Chapter Life Subsceibers 232 Chapter Scholaeship Recoeds 233 Omiceon Alumni of Unknown Address 238 Expulsion Notice 238 In Memoeiam 239 Edwaed a. Bradford, Beta '73 Jay Feank Chappell, Omega '20 Eael W. DeMoe, Rho '92 Chauncey M. Depew, Beta '56 Rev. Edw. C. Feillowes> Beta '88 Colonel Moses M. -

ESSSAR Masthead

EMPIRE PATRIOT Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Descendants of America’s First Soldiers Volume 10 Issue 1 February 2008 Printed Four Times Yearly THE CONCLUSION OF . THE PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN In Summary: We started this journey several issues ago beginning with . LANDING AT THE HEAD OF ELK - Over 260 British ships arrived at Head of Elk, Maryland. Washington was ready. The trip took overly long, horses died by the hundreds. British General Howe was anxious to move on, but first he had to unload his massive armada. ON THE MARCH TO BRANDYWINE - Howe heads for Philadelphia. Washington blocks the path. On the way to their first engagement of 1777, Washington exposes himself to capture, Howe misses an opportunity, the rains fall, and everyone seems prepared for what happens next. THE BATTLE OF BRANDYWINE- The first battle in the campaign. Howe conceives and executes a daring 17 mile march catching Washington by surprise. The Continental Army is impressive, but the day belongs to the British. THE BATTLE OF THE CLOUDS Both armies were poised for another major engagement Five days after the Battle of Brandywine, a confrontation is rained out PAOLI MASSACRE Bloody bayonets in a midnight raid Mad” Anthony Wayne, assigned to attack the rear guard of the British army, is himself surprised in a “dirty” early morning raid. MARCH TO GERMANTOWN Washington prepares to win back the capital Congress flees Philadelphia as the British occupy the city amid chaos and fear. THE BATTLE OF GERMANTOWN The battle is fought in and around a mansion. For the first time the British retreat during battle, but fog and confusion turned the American advance around. -

Porcellian Club Centennial, 1791-1891

nia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY W CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO NEW CLUB HOUSE PORCELLIAN CLUB CENTENNIAL 17911891 CAMBRIDGE printed at ttjr itttirnsiac press 1891 PREFATORY THE new building which, at the meeting held in Febru- ary, 1890, it was decided to erect has been completed, and is now occupied by the Club. During the period of con- struction, temporary quarters were secured at 414 Harvard Street. The new building stands upon the site of the old building which the Club had occupied since the year 1833. In order to celebrate in an appropriate manner the comple- tion of the work and the Centennial Anniversary of the Founding of the Porcellian Club, a committee, consisting of the Building Committee and the officers of the Club, was chosen. February 21, 1891, was selected as the date, and it was decided to have the Annual Meeting and certain Literary Exercises commemorative of the occasion precede the Dinner. The Committee has prepared this volume con- taining the Literary Exercises, a brief account of the Din- ner, and a catalogue of the members of the Club to date. A full account of the Annual Meeting and the Dinner may be found in the Club records. The thanks of the Committee and of the Club are due to Brothers Honorary Sargent, Isham, and Chapman for their contribution towards the success of the Exercises Literary ; also to Brother Honorary Hazeltine for his interest in pre- PREFATORY paring the plates for the memorial programme; also to Brother Honorary Painter for revising the Club Catalogue. GEO. B. SHATTUCK, '63, F. R. APPLETON, '75, R. -

Lincoln and Emancipation: a Man's Dialogue with His Times

DOCUMRNT flitSUP48 ED 032 336 24 TE 499 934 By -Minear, Lawrence Lincoln and Emancipation: A Man's Dialogue with His Times. Teacher and Student Manuals. Amherst Coll., Mass. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DREW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Report No -CRP -H 1 68 Bureau No-BR-S-1071 Pub Date 66 Contract -OEC 5-10-158 Note-137p. EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors -*Civil War (United States),*Curriculum Guides, Democracy, Government Role, *Leadership Qualities, Leadership Styles, Political Influences, Political Issues, Political Power, Role Conflict, Secondary Education, Self Concept. *Slavery. *Social Studies. United States History Identifiers -*Abraham Lincoln. Emancipation Proclamation Focusing on Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation of the Negro, this social studies unit explores the relationships among men and events, the qualities of leadership. and the nature of historical change. Lincoln's evolving views of the Negro are examined through (1) the historical context in which Lincoln's beliefs about Negroes took shape, (2) the developments in Lincoln's political life, from 1832 through 1861, which affected his beliefs about Negroes, (3) the various military, political.. and diplomatic pressures exerted on Lincoln as President which made him either the captive or master of events, (4) the two Emancipation Proclamations and the relationship between principle and expediency, (5) the impact of the emancipation on Lincoln's understanding of the conduct and purposes of the war and the conditions of peace, and (6) Lincoln's views on reconstruction in relation to emancipation, Inlcuded are suggestions for further reading, maps. charts. and writings from the period which elucidate Lincoln's political milieu. -

AUDIENCE of the FEAST of the FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776

AUDIENCE OF THE FEAST OF THE FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ As a point of understanding never mentioned before in any Akurian Lessons or Scripts and for those who read these presents: When The Most High, Himself, and anyone else in The Great Presence speaks, there is massive vision for all, without exception, in addition to the voices that there cannot be any misunderstanding of any kind by anybody for any reason. It is never a situation where a select sees one vision and another sees anything else even in the slightest detail. That would be a deliberate deception, and The Most High will not tolerate anything false that is not identified as such in His Presence. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Encamped and Headquartered in full array at Philun, 216th Realm, 4,881st Abstract, we received Call to present ourselves before The Most High, ALIHA ASUR HIGH, in accordance with standing alert. In presence with fellow Horsemen Immanuel, Horus and Hammerlin and our respective Seconds, I requested all available Seniors or their respective Seconds to attend in escort. We presented ourselves in proper station and I announced our Company to The Most High in Grand Salute as is the procedure. NOTE: Bold-italics indicate emphasis: In the Script of The Most High, by His direction; in any other, emphasis is mine. The Most High spoke: ""Lord King of Israel El Aku ALIHA ASUR HIGH, Son of David, Son of Fire, you that is Named of My Own Name, know that I am pleased with your Company even unto the farthest of them on station in the Great Distances. -

Embracing Entrepreneurship

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses Perkins Thesis and Dissertations Spring 5-15-2021 Embracing Entrepreneurship Naomy Sengebwila [email protected] Naomy Nyendwa Sengebwila Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_ministry_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Folklore Commons, Food Security Commons, Food Studies Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Regional Economics Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social Justice Commons, Social Work Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Sengebwila, Naomy and Sengebwila, Naomy Nyendwa, "Embracing Entrepreneurship" (2021). Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses. 9. https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_ministry_etds/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Perkins Thesis and Dissertations at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Embracing Entrepreneurship How Christian Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship can Lead to Sustainable Communities in Zambia and Globally Approved by: Dr. Hal Recinos/Dr. Robert Hunt ___________________________________ Advisors Dr. Hugo Magallanes ___________________________________ -

General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 917 SO 031 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug. 30, 1869. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); *Donors; *Meetings; *Private Financial Support; *Public History; Recognition (Achievement); *Reconstruction Era IDENTIFIERS Biodata; Lee (Robert E); *Peabody (George) ABSTRACT This paper discusses the chance meeting at White Sulphur Springs (West Virginia) of two important public figures, Robert E. Lee and George Peabody, whose rare encounter marked a symbolic turn from Civil War bitterness toward reconciliation and the lifting power of education. The paper presents an overview of Lee's life and professional and military career followed by an overview of Peabody's life and career as a banker, an educational philanthropist, and one who endowed seven Peabody Institute libraries. Both men were in ill health when they visited the Greenbrier Hotel in the summer of 1869, but Peabody had not long to live and spent his time confined to a cottage where he received many visitors. Peabody received a resolution of praise from southern dignitaries which read, in part: "On behalf of the southern people we tender thanks to Mr. Peabody for his aid to the cause of education...and hail him benefactor." A photograph survives that shows Lee, Peabody, and William Wilson Corcoran sitting together at the Greenbrier. Reporting that Lee's own illness kept him from attending Peabody's funeral, the paper describes the impressive and prolonged international services in 1870. -

Read the Westchester Guardian

Vol. VI, No. XVIII Thursday, May 3, 2012,,,,$1.00 Westchester’s Most Influential Weekly RICH MONETTI Left Brain, New Rochelle to Right Brain Page 3 JOHN F. McMULLEN SUFFER Spreadsheets Page 4 GreeNR Concerns SHERIF AWAD By PEGGY GODFREY, Page 23 Tahrir Square Page 6 ROBERT SCOTT Hotel Beautiful Page 10 MARK JEFFERS Sports Scene Page 18 ROGER WITHERSPOON Used Car Market Page 20 MARY C. MARVIN Water, Water, Everywhere Page 22 In Memoriam: EDWARD I. KOCH Stopping Money Mary Elizabeth Pollis Corrupting Elections See page 12 Page 24 WWW.WESTCHESTERGUARDIAN.COM Page 26 THE WESTCHESTER GUARDIAN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2012 CLASSIFIED ADS LEGAL NOTICES Office Space Available- FAMILYFAMILY COURTCOURT OFOF THETHE STATESTATE OFOF NEWNEW YORKYORK Prime Location, Yorktown Heights COUNTY OF WESTCHESTER 1,0001,000 Sq.Sq. Ft.:Ft.: $1800.$1800. ContactContact Wilca:: 914.632.1230914.632.1230 InIn thethe MatterMatter ofof ORDERORDER TOTO SHOWSHOW CAUSECAUSE SUMMONS AND INQUEST NOTICE Prime Retail - Westchester County Chelsea Thomas (d.o.b. 7/14/94), Best Location in Yorktown Heights A Child Under 21 Years of Age DktDkt Nos.Nos. NN-10514/15/16-10/12CNN-10514/15/16-10/12C 11001100 Sq.Sq. Ft.Ft. StoreStore $3100;$3100; 12661266 Sq.Sq. Ft.Ft. storestore $2800$2800 andand 450450 Sq.Sq. Ft.Ft. THE WESTCHESTER GUARDIAN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2012 Store $1200. Page 3 Adjudicated to be Neglected by NN-2695/96-10/12BNN-2695/96-10/12B FUFU No.:No.: 2230322303 Page 2 THE WTHEEST CWESTCHESTERHESTER GUARD IGUARDIANAN THURSDAY,THURSDAY,THURSDAY FEBRUARY MARCH 23, MAY 2012Suitable 29, 3, 2012 for any type of business. -

Commission on Public Art Inventory Review Online Comment Submissions the Public Comments in This Document Were Collected from Au

Commission on Public Art inventory review online comment submissions The public comments in this document were collected from August 15 to September 5. They are in response to a call from Mayor Greg Fischer, encouraging the public to add their voice to the review of public art that can be interpreted to honor bigotry, discrimination, racism and/or slavery. 40204: I am not opposed to removing the Castleman statue. I would miss having a horse in the neighborhood, however, so if it could be replaced by another rider, perhaps Oliver Lewis and Aristides, the first KY Derby winners. That would be cool. Any statue with Confederate imagery should be removed. Period. 40299: We should not have public murals and statues of leaders of the confederacy. The bottom line is that these men of the confederacy fought to keep hatred, bigotry and racism alive. I don't want our city to have statues honoring these men, because I know Louisville is an inclusive community dedicated to bringing different folks together. 40212: Remove all statues glorifying these traitors. I can’t imagine what a PoC feels about these abominations. 40243: Please leave history ALONE... 40208: A democracy should have monuments celebrating the oppressed and not the oppressors. We need to tear down any monuments celebrating the Confederacy. I also think you should add to this list nude portraits, paintings objectifying women, and paintings featuring people in poverty. I would recommend going through the library and removing all books before 1975 and blocking all websites that involve actual thinking. History has been written, to ignore it is unwise. -

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor.