The Confederation of Newfoundland and Canada, 1945-1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winterwinter June10june10 OL.Inddol.Indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents |

BBarNewsarNews WinterWinter JJune10une10 OL.inddOL.indd 1 33/6/10/6/10 111:46:191:46:19 AMAM | Contents | 2 Editor’s note 4 President’s column 6 Letters to the editor 8 Bar Practice Course 01/10 9 Opinion A review of the Senior Counsel Protocol Ego and ethics Increase the retirement age for federal judges 102 Addresses 132 Obituaries 22 Recent developments The 2010 Sir Maurice Byers Address Glenn Whitehead 42 Features Internationalisation of domestic law Bernard Sharpe Judicial biography: one plant but Frank McAlary QC several varieties 115 Muse The Hon Jeff Shaw QC Rake Sir George Rich Stephen Stewart Chris Egan A really rotten judge: Justice James 117 Personalia Clark McReynolds Roger Quinn Chief Justice Patrick Keane The Hon Bill Fisher AO QC 74 Legal history Commodore Slattery 147 Bullfry A creature of momentary panic 120 Bench & Bar Dinner 2010 150 Book reviews 85 Practice 122 Appointments Preparing and arguing an appeal The Hon Justice Pembroke 158 Crossword by Rapunzel The Hon Justice Ball The Federal Magistrates Court 159 Bar sports turns 10 The Hon Justice Nicholas The Lady Bradman Cup The Hon Justice Yates Life on the bench in Papua New The Great Bar Boat Race Guinea The Hon Justice Katzmann The Hon Justice Craig barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2010 Bar News Editorial Committee ISSN 0817-0002 Andrew Bell SC (editor) Views expressed by contributors to (c) 2010 New South Wales Bar Association Keith Chapple SC This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted Bar News are not necessarily those of under the Copyright Act 1968, and subsequent Mark Speakman SC the New South Wales Bar Association. -

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Bibiical Drama by Chester N. Scoville a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with The

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English BibIical Drama by Chester N. Scoville A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto O Copyright by Chester N. Scoville (2000) National Library Bibiiotheque nationale l*l ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rwW~gtm OttawaON KlAûîU4 OtÈewaûN K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Department of English, University of Toronto The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Biblical Dnma by Chester N. Scovilie Much past criticism of character in Middle English drarna has fallen into one of two rougtily defined positions: either that early drama was to be valued as an example of burgeoning realism as dernonstrated by its villains and rascals, or that it was didactic and stylized, meant primarily to teach doctrine to the faithfùl. -

Rural Medical Lives and Time J

Document generated on 10/02/2021 8:44 a.m. Newfoundland Studies Rural Medical Lives and Time J. T. H. Connor Volume 23, Number 2, Fall 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds23_2re01 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 0823-1737 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Connor, J. T. H. (2008). Review of [Rural Medical Lives and Time]. Newfoundland Studies, 23(2), 231–244. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ REVIEW ESSAY Rural Medical Lives and Times J.T.H. CONNOR Noel Murphy. Cottage Hospital Doctor: The Medical Life of Dr. Noel Murphy, 1945-1954. (Edited by Marc Thackray) St. John’s, Creative Publishers, 2003, ISBN 1894294726. John K. Crellin. The Life of a Cottage Hospital: The Bonne Bay Experience. St. John’s, Flanker Press, 2007, ISBN 1897317050; ISBN 9781897317051. Esther Slaney Brown. Labours of Love: Midwives of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John’s, DRC Publishing, 2007, ISBN 0978343409; ISBN 9780978343408. PEOPLE WHO LIVE IN rural or remote settlements, especially in the North, are subject to illness and injury like their southern urban counterparts — even more so due to harsh environments and climate, dangerous occupational conditions, and increased distance from health services. -

Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities?

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities? Authors(s) Keenan, Marie Publication date 2014-11-27 Publisher University College Dublin. School of Applied Social Science Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/6247 Downloaded 2021-09-26T18:57:06Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities? A Collaborative Study on the potential of Restorative Justice in Sexual Crime in Ireland DR. MARIE KEENAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN This report is based on the results of a collaborative study between Facing Forward, Ms Bernadette Fahy and Dr Marie Keenan. The Research Assistant Interns who helped with data analysis [supported by the Government JobBridge Scheme] also made a significant contribution to this research and sincere thanks are due to Cian O’ Concubhair, Olive Lyons, Graham Loftus, Martin Mulrennan, Hannah Gilmartin, Andrea Kennedy, Patrice Reilly and Chris Kelly. Cian O’Concubhair’s written work on accountability mechanisms in legal systems enormously enhanced particular sections of this report. Thanks are due to UCD’s Geary Institute for providing office accommodation for the Research Assistant Interns during -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

Exerpt from Joey Smallwood

This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 499 TOPIC 6.1 Did Newfoundland make the right choice when it joined Canada in 1949? If Newfoundland had remained on its own as a country, what might be different today? 6.1 Smallwood campaigning for Confederation 6.2 Steps in the Confederation process, 1946-1949 THE CONFEDERATION PROCESS Sept. 11, 1946: The April 24, 1947: June 19, 1947: Jan. 28, 1948: March 11, 1948: Overriding National Convention The London The Ottawa The National Convention the National Convention’s opens. delegation departs. delegation departs. decides not to put decision, Britain announces confederation as an option that confederation will be on on the referendum ballot. the ballot after all. 1946 1947 1948 1949 June 3, 1948: July 22, 1948: Dec. 11, 1948: Terms March 31, 1949: April 1, 1949: Joseph R. First referendum Second referendum of Union are signed Newfoundland Smallwood and his cabinet is held. is held. between Canada officially becomes are sworn in as an interim and Newfoundland. the tenth province government until the first of Canada. provincial election can be held. 500 The Referendum Campaigns: The Confederates Despite the decision by the National Convention on The Confederate Association was well-funded, well- January 28, 1948 not to include Confederation on the organized, and had an effective island-wide network. referendum ballot, the British government announced It focused on the material advantages of confederation, on March 11 that it would be placed on the ballot as especially in terms of improved social services – family an option after all. -

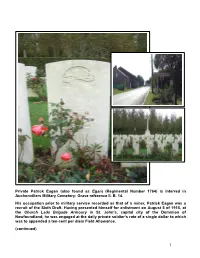

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

Language Planning and Education of Adult Immigrants in Canada

London Review of Education DOI:10.18546/LRE.14.2.10 Volume14,Number2,September2016 Language planning and education of adult immigrants in Canada: Contrasting the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia, and the cities of Montreal and Vancouver CatherineEllyson Bem & Co. CarolineAndrewandRichardClément* University of Ottawa Combiningpolicyanalysiswithlanguagepolicyandplanninganalysis,ourarticlecomparatively assessestwomodelsofadultimmigrants’languageeducationintwoverydifferentprovinces ofthesamefederalcountry.Inordertodoso,wefocusspecificallyontwoquestions:‘Whydo governmentsprovidelanguageeducationtoadults?’and‘Howisitprovidedintheconcrete settingoftwoofthebiggestcitiesinCanada?’Beyonddescribingthetwomodelsofadult immigrants’ language education in Quebec, British Columbia, and their respective largest cities,ourarticleponderswhetherandinwhatsensedemography,languagehistory,andthe commonfederalframeworkcanexplainthesimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwo.These contextualelementscanexplainwhycitiescontinuetohavesofewresponsibilitiesregarding thesettlement,integration,andlanguageeducationofnewcomers.Onlysuchunderstandingwill eventuallyallowforproperreformsintermsofcities’responsibilitiesregardingimmigration. Keywords: multilingualcities;multiculturalism;adulteducation;immigration;languagelaws Introduction Canada is a very large country with much variation between provinces and cities in many dimensions.Onesuchaspect,whichremainsacurrenthottopicfordemographicandhistorical reasons,islanguage;morespecifically,whyandhowlanguageplanningandpolicyareenacted -

President's Report

July 2018 President’s Report by Gary Walsh th The 2018 annual general meeting was A main initiative for our 75 Ocean. He was most interested in the th held on May 30 and was well Anniversary celebrations was the history of the Crow's Nest and artifacts attended with lively discussions on a creation of the Crow's Nest Officers’ and appreciated the hospitality he was variety of issues. As with all AGMs a Club Scholarship tenable at Memorial shown. Manfred is now a life time new slate of officers and board University. I am delighted to confirm member and we wish to thank him for members were elected and the that Mr. Daniel Browne, a music major, his generosity. has been awarded the very first upcoming year looks to be a busy one. I The funds will be directed where the want to thank outgoing secretary scholarship. His high academic individual wishes to see them used or, achievements combined with his Wayne Ludlow and outgoing treasurer if no specific request is made, be used volunteer work meets our criteria for Mary Grouchy for their many years of toward the preservation of the dedicated service and also outgoing awards and he is a most worthy artifacts, building upgrades, the board members Ian Wheeler and Rob recipient. Daniel will visit the Club later scholarship fund or other Club Shea for their most valued this year and we look forward to initiatives. contributions. I would also like to thank meeting him. The annual lobster dinner was held on the existing board members and Bruce Honorary life time member Rosemary June 2nd and next scheduled Club Bennett with the Crow's Nest Military Barron recently passed away and her dinner will be in September, but pub Artifacts Association who have all fondness for the Crow's Nest was lunches will be served on Fridays kindly offered to serve another term. -

Government of Canada's Digital Policy

Feedback on the Direction for a New Government of Canada Digital Policy By: The Information and Communications Technology Council 116 Lisgar Street, Suite 300 Ottawa, Ontario [email protected] 613-237-8551 Thank you for the opportunity to provide feedback to the proposed Government of Canada Digital Policy. The Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC) welcomes the opportunity to provide input to this important initiative. It is also important the policy is planned to be an iterative, living policy framework as a static policy is an anathema to all digital initiatives. Government digital initiatives should be conducted in collaboration with private sector leaders to ensure that the expertise in these companies is utilized and that government does not unnecessarily encroach on/repli- cate capabilities existing in the private sector. Feedback on the Digital Policy Proposal: How would you see these proposals improve your life in using Government of Canada services? In the age of data-as-an-economy, eCommerce, A.I, IoT, and smart cities, the government should focus its strategy on being “Digital First”. Such a policy measure will have the beneficial effect of enabling citizens to be more digital savvy and entice companies that transact with government to further adopt technologies and heighten their digital advantage in a global economy. The Canadian government needs to articulate a clear digital services strategy that will enable faster and efficient services by 2023 (for instance) in: e-Identity, e-Health, e-Voting, etc. Such a strategy will provide Canadians and businesses (national & international) with the clarity and confidence that the government of Canada is paving the way for a competitive and advanced economy and society. -

City of St. John's Archives the Following Is a List of St. John's

City of St. John’s Archives The following is a list of St. John's streets, areas, monuments and plaques. This list is not complete, there are several streets for which we do not have a record of nomenclature. If you have information that you think would be a valuable addition to this list please send us an email at [email protected] 18th (Eighteenth) Street Located between Topsail Road and Cornwall Avenue. Classification: Street A Abbott Avenue Located east off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Abbott's Road Located off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Aberdeen Avenue Named by Council: May 28, 1986 Named at the request of the St. John's Airport Industrial Park developer due to their desire to have "oil related" streets named in the park. Located in the Cabot Industrial Park, off Stavanger Drive. Classification: Street Abraham Street Named by Council: August 14, 1957 Bishop Selwyn Abraham (1897-1955). Born in Lichfield, England. Appointed Co-adjutor Bishop of Newfoundland in 1937; appointed Anglican Bishop of Newfoundland 1944 Located off 1st Avenue to Roche Street. Classification: Street Adams Avenue Named by Council: April 14, 1955 The Adams family who were longtime residents in this area. Former W.G. Adams, a Judge of the Supreme Court, is a member of this family. Located between Freshwater Road and Pennywell Road. Classification: Street Adams Plantation A name once used to identify an area of New Gower Street within the vicinity of City Hall. Classification: Street Adelaide Street Located between Water Street to New Gower Street. Classification: Street Adventure Avenue Named by Council: February 22, 2010 The S.