Seriality in a Culture of Binging: Comics, Television, and the Challenge of “Doing Both”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Summer Catalog 2020

5)&5*/:#00,4503& Summer Catalog 2020 Summer books for readers of all ages Arts and Crafts……………………………………………………………. p.1 Biography and Autobiography………………………………...……. p. 1-2 Business and Economics……………………………………...……….. p. 2-4 Comics and Graphic Novels……………………………..…………… p. 4-6 Computers and Gaming………………………………...…….……….. p. 6 Cooking……………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Education…………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Family and Relationships………………………………...……………. p. 6 Adult Fiction………………………………………………….……………. p. 7-10 Health and Fitness…………………………………………..…………… p. 10 History……………………………………………………………………….. p. 10 Humor…………………………………………………………….………….. p. 11 Kids Fiction for Kids…………………………………………………… p. 11-18 Nonfiction for Kids……………………………………………… p. 18-20 Social Studies Language Arts………………………………………...........…….. p. 21 Law………………………………………………………….….....….. p. 21 Literary Collections……………………………………..…........ p. 21 Math…………………………………………………………..…....... p. 21 Philosophy…………………………………………………..…...... p. 21 Table of Contents of Table Politics…………………………………………………………........ p. 21-22 Psychology…………………………………………………......…. p. 23 Religion……………………………………....…………………..… p. 23 Science………………………………………....…………………... p. 23 Self-Help……………………………………………….………………....... p. 23-25 Social Science…………………………………………………………….. p. 25 Sports………………………………………………………………………… p. 25 True Crime…………………………………………………………………. p. 25 Young Adult Fiction……………………………………………………................ p. 25-27 Nonfiction……………………………………………................… p. 27-28 Buy Online and Pick-up at Store or Shop and Ship to Home tinybookspgh.com/online -

CITIZEN #187-188.Indd

Salut vous tous, les AstroCitizens ! «nous sommes décidément bien trop en retard pour vous proposer un édito digne de édito ce nom.... gageons que le mois prochain sera diff érent !» zut je vous l’ai déjà dit ! à ma décharge, vous avez entre les mains un DOUBLE Citizen avec, dedans, rien moins que les news de Juillet ET d’Aout ! Au mois prochain et d’ici là : à vous de jouer !!!! Damien, Fred & Jérôme – JUILLET & AOUT 2017 news de la cover du mois : ROM VS TRANSFORMERS par Alex Milne Un peu de lexique... Le logo astrocity et la super-heroïne “astrogirl” ont été créés par Blackface.Corp et sont la propriété GN pour Graphic novel : La traduction littérale de ce terme est «roman graphique» exclusive de Damien Rameaux & Frédéric Dufl ot au OS pour One shot : Histoire en un épisode, publié le plus souvent à part de la continuité régulière. titre de la société AstroCity SARL. Mise en en page et charte graphique du magazine Citizen et du site TP pour Trade paperback : Un trade paperback est un recueil en un volume unique de plusieurs comic-books qui regroupe un arc complet 187-188 internet astrocity.fr par Blackface.Corp HC pour Hard Cover : Un hard cover est un recueil en version luxueuse, grand format et couverture cartonnée de plusieurs comic-books. Prem HC (Premiere HC) : Un premiere hard cover est un recueil en version luxe (format comics et couverture cartonnée) de plusieurs comic-books. # SC pour Soft Cover : Un soft cover est un recueil en version luxueuse, grand format et couverture souple de plusieurs comic-books. -

The Only Way Is Down: Lark and Brubaker's Saga As '70S Cinematic

The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir an Essay by Ryan K Lindsay from THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL EDITED BY RYAN K. LINDSAY SEQUART RESEARCH & LITERACY ORGANIZATION EDWARDSVILLE, ILLINOIS The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay Copyright © 2013 by the respective authors. Daredevil and related characters are trademarks of Marvel Comics © 2013. First edition, February 2013, ISBN 978-0-5780-7373-6. All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts used for review or scholarly purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including electronic, without express consent of the publisher. Cover by Alice Lynch. Book design by Julian Darius. Interior art is © Marvel Comics; please visit marvel.com. Published by Sequart Research & Literacy Organization. Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay. Assistant edited by Hannah Means-Shannon. For more information about other titles in this series, visit sequart.org/books. The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir by Ryan K Lindsay Cultural knowledge indicates that Daredevil is the noir character of the Marvel Universe. This assumption is an unchallenged perception that doesn’t actually hold much water under any major scrutiny. If you add up all of Daredevil’s issues to date, the vast majority are not “noir.” Mild examination exposes Daredevil as one of the most diverse characters who has ever been written across a series of genres, from swashbuckling romance, to absurd space opera, to straight up super-heroism and, often, to crime saga. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Released 4Th January 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS AUG160126

Released 4th January 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS AUG160126 ASTRO BOY OMNIBUS TP VOL 06 AUG160127 NGE SHINJI IKARI RAISING PROJECT OMNIBUS TP VOL 02 NOV160041 RISE OF THE BLACK FLAME #5 (OF 5) SEP160081 WORLD OF TANKS #4 DC COMICS NOV160198 AQUAMAN #14 NOV160199 AQUAMAN #14 VAR ED NOV160208 BATMAN #14 NOV160209 BATMAN #14 VAR ED OCT160300 CATWOMAN TP VOL 06 FINAL JEOPARDY NOV160214 CYBORG #8 NOV160215 CYBORG #8 VAR ED NOV160295 DC COMICS BOMBSHELLS #21 NOV160298 DEATH OF HAWKMAN #4 (OF 6) NOV160353 EVERAFTER FROM THE PAGES OF FABLES #5 NOV160293 FALL AND RISE OF CAPTAIN ATOM #1 (OF 6) NOV160294 FALL AND RISE OF CAPTAIN ATOM #1 (OF 6) VAR ED NOV160307 FLINTSTONES #7 NOV160308 FLINTSTONES #7 VAR ED OCT160307 GRAYSON TP VOL 05 SPYRALS END NOV160228 GREEN ARROW #14 NOV160229 GREEN ARROW #14 VAR ED OCT160293 GREEN ARROW TP VOL 01 LIFE & DEATH OF OLIVER QUEEN (REBIRTH) NOV160232 GREEN LANTERNS #14 NOV160233 GREEN LANTERNS #14 VAR ED NOV160240 HARLEY QUINN #11 NOV160241 HARLEY QUINN #11 VAR ED NOV160299 INJUSTICE GROUND ZERO #3 NOV160179 JUSTICE LEAGUE #12 (JL SS) NOV160180 JUSTICE LEAGUE #12 VAR ED (JL SS) NOV160183 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA THE ATOM REBIRTH #1 NOV160184 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA THE ATOM REBIRTH #1 VAR ED NOV160163 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) NOV160164 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) CONNER VAR ED NOV160165 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) MADUREIRA VAR ED NOV160302 MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO #4 (OF 6) NOV160248 NIGHTWING #12 NOV160249 NIGHTWING #12 VAR ED NOV160314 SCOOBY DOO WHERE ARE YOU #77 NOV160279 SHADE -

Lawyer Bracket.Xlsx

All-Time Best Fictonal Lawyer 1st Round 2nd Round 3rd Round 4th Round 5th Round 6th Round 5th Round 4th Round 3rd Round 2nd Round 1st Round 09-Dec 23-Dec 30-Dec 06-Jan 13-Jan 20-Jan 13-Jan 06-Jan 30-Dec 16-Dec 02-Dec 1 Lionel Hutz (Simpsons) Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird) 1 Lionel Hutz Atticus Finch 16 Steve Dallas (Bloom County comic strip) Michael Clayton (Michael Clayton) 16 8 Johnnie Cochran (South Park) Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. (The Paper Chase) 8 Johnnie Cochran Lesra Martin 9 She-Hulk (Marvel Comics) Lesra Martin (The Hurricane) 9 5 Phoenix Wright (Gyakuten Saiban: Sono "Shinjitsu", Igiari!) Lt. Daniel Kaffee (A Few Good Men) 5 Phoenix Wright Lt. Daniel Kaffee 12 Foggy Nelson (Daredevil) Reggie Love (The Client) 12 4 Harvey Birdman (Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law) Henry Drummond (Inherit the Wind) 4 FINAL Harvey Birdman Vinny Gambini 13 Michelle the Lawyer (American Dad) Vinny Gambini (My Cousin Vinny) 13 6 Hyper-Chicken (Futerama) Mitch McDeere (The Firm) 6 Hyper-Chicken Mick Haller 11 Lawyer Morty (Rick and Morty) Mick Haller (The Lincoln Lawyer) 11 3 Harvey Dent (Batman) Elle Woods (Legally Blond) 3 Harvey Dent Elle Woods 14 Robin (DC Earth-Two) Martin Vail (Prinal Fear) 14 7 Blue-Haired Lawyer (Simpsons) Joe Miller (Philadelphia) 7 Blue-Haired Lawyer Joe Miller 10 Judge Dredd (Judge Dredd) Hans Rolfe (Judgement at Nuremberg) 10 2 Matt Murdock (Daredevil) Erin Brockovich (Erin Brockovich) 2 Matt Murdock Erin Brockovich 15 Margot Yale (Gargoyles) Jake Brigance (A Time to Kill) 15 FINAL FOUR CHAMPION FINAL FOUR 1 Ben Matlock -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Marvel Modern Age New Rules Errata Version 2017.02

Marvel Modern Age New Rules Errata Version 2017.02 Shared in Multiple Sets COLOR-COORDINATED: [Character] can use Outwit, but only to counter [Color] powers. COLOR-COORDINATED: Outwit, but only to choose standard [Color] powers. Applies to: Deadpool and X-Force 101 Terror Deadpool and X-Force Fast Forces 007 Deadpool, 008 Foolkiller, 009 Madcap, 010 Slapstick, 011 Solo, 012 Stingray WizKids Exclusives M-G004 Supreme Intelligence OMNI-WAVE PROJECTOR: Supreme Intelligence may target characters anywhere on the map with a ranged combat attack regardless of range and line of fire unless there is an opposing character of 100 points or more adjacent to him. When Supreme Intelligence targets a character with an attack, if that character isn't within range and line of fire, his damage value is 3 and is locked. OMNI-WAVE PROJECTOR: When Supreme Intelligence makes a range attack, he may target characters regardless of range and line of fire unless there is an opposing character of 100 points or more adjacent to him. When Supreme Intelligence targets a character with an attack, if that character isn't within range and line of fire, his maximum damage value is 3. M-026 Ghost Rider CLENCHED FIST OF GOD: Ghost Rider can use Pulse Wave as if she had a range of 8. When she does and her damage value is replaced with 1, hit characters with 2 action tokens are dealt 2 damage instead. CLENCHED FIST OF GOD: Pulse Wave with a range of 8. When Ghost Rider uses it, if she targets more than one character, hit characters with 2 action tokens are dealt 2 damage instead of 1. -

Table of Contents Introduction 2 Young Readers 3 Middle School 7 High School 14 Older Teens 22

An Annotated Bibliography by Jack Baur and Amanda Jacobs-Foust with Carla Avitabile, Casey Gilly, Jessica Lee, Holly Nguyen, JoAnn Rees, Shawna Sherman, and Elsie Tep May 17th, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Young Readers 3 Middle School 7 High School 14 Older Teens 22 Prepared by BAYA for the California Library Association 1 Introduction It’s no secret that comics (or “graphic novels,” if you prefer) are hot items in the library world these days. Oh, we’ve known that for years, but recently publishers have been getting into the game in a big way. Too big, arguably. As publishers struggle, it seems like more and more they are turning to graphic novels as new revenue streams, to diversify existing properties, or as ways to repackage old content. With the deluge of titles coming at us, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for a librarian who isn’t deeply invested in their GN collection or tuned into the world of comics publishing to discern the excellent titles from the merely popular, and the quality from the... well, crap. And oh there’s a lot of crap out there these days... But there’s a whole lot of great stuff, too. Comics are a wonderful and unique medium, which allow any kind of story or instruction to be delivered in a way that is fun, engaging, and accessible. Just like other storytelling forms, the content can be simple and amusing, or it can be deep and challenging. It’s no surprise that comics are seeing such a jump in popularity and acceptance now. -

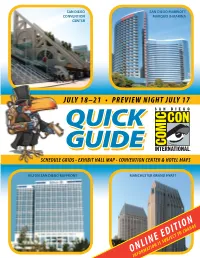

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

Maskierte Helden

Aleta-Amirée von Holzen Maskierte Helden Zur Doppelidentität in Pulp-Novels und Superheldencomics Populäre Literaturen und Medien 13 Herausgegeben von Ingrid Tomkowiak Aleta-Amirée von Holzen Maskierte Helden Zur Doppelidentität in Pulp-Novels und Superheldencomics DiePubliziert Druckvorstufe mit Unterstützung dieser Publikation des Schweizerischen wurde vom Nationalfonds Schweizerischen Nationalfondszur Förderung derzur wissenschaftlichenFörderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. Forschung unterstützt. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Zürich im Frühjahrssemester 2018 auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Ingrid Tomkowiak und Prof. Dr. Klaus Müller-Wille als Dissertation angenommen. Weitere Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm: www.chronos-verlag.ch Umschlagbild: Steve Ditko (Zeichner), Stan Lee (Autor) et al.: «Unmasked by Dr. Octopus», in: Spider-Man Classics Vol. 1, No. 13, April 1994, S. 5 (Nachdruck aus: The Amazing Spider-Man 12, Mai 1964). © Marvel Comics © 2019 Chronos Verlag, Zürich Print: ISBN 978-3-0340-1508-0 E-Book (PDF): DOI 10.33057/chronos.1508 5 Inhalt Einleitung 7 Maskerade und Geheimnis 17 Verbergen und Zeigen – Enthüllung durch Verhüllung 18 Geheimnisbedrohung und -bewahrung: Narrative Koordinaten der Doppelidentität 30 Masken, Rollen, Identitäten 45 «Die ganze Welt ist eine Bühne» – die metaphorische Maske 49 Interaktion und Identität, Konformität und Einzigartigkeit 56 Interpretationsansätze zur Doppelidentität (der Mann aus Stahl und der unscheinbare Reporter) 67 Die zivile Identität