EZH2 Mediates Epigenetic Silencing of Neuroblastoma Suppressor Genes CASZ1, CLU, RUNX3 and NGFR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casz1 Controls Higher-Order Nuclear Organization in Rod Photoreceptors

Casz1 controls higher-order nuclear organization in rod photoreceptors Pierre Mattara,1,2, Milanka Stevanovica,b, Ivana Nadc, and Michel Cayouettea,b,d,e,1 aCellular Neurobiology Research Unit, Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal, Montréal, QC H2W 1R7, Canada; bDepartment of Anatomy and Cell Biology, McGill University, Montréal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada; cDepartment of Cell and Molecular Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1H 8M5, Canada; dDivision of Experimental Medicine, McGill University, Montréal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada; and eDepartment of Medicine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC H3T 1J4, Canada Edited by Chris Q. Doe, HHMI and University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved July 11, 2018 (received for review February 19, 2018) Genome organization plays a fundamental role in the gene- scattering in the retina (7). While previous studies have provided expression programs of numerous cell types, but determinants a descriptive framework for understanding rod genome organi- of higher-order genome organization are poorly understood. In zation, determinants of this organization remain largely elusive, the developing mouse retina, rod photoreceptors represent a with only the lamin B receptor (Lbr) identified so far (8). good model to study this question. They undergo a process called Here, we report that Casz1 is a determinant of rod photore- “chromatin inversion” during differentiation, in which, as opposed ceptor nuclear organization. Casz1 is a zinc finger transcription to classic nuclear organization, heterochromatin becomes localized factor required for both heart and vascular development, and its to the center of the nucleus and euchromatin is restricted to the germline inactivation causes embryonic lethality (9–11). Casz1 is periphery. -

CHARACTERIZATION of the CASZ1-DEPENDENT MECHANISMS ESSENTIAL for CARDIOMYOCYTE DEVELOPMENT Kerry M. Dorr a Dissertation Submitte

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE CASZ1-DEPENDENT MECHANISMS ESSENTIAL FOR CARDIOMYOCYTE DEVELOPMENT Kerry M. Dorr A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Genetics and Molecular Biology in the School of Medicine. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Frank Conlon Terry Magnuson Li Qian Joan Taylor Andy Wessels © 2015 Kerry M. Dorr ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kerry M. Dorr: Characterization of the Casz1-Dependent Mechanisms Essential for Cardiomyocyte Development (Under the direction of Frank L. Conlon) The heart is one of the first structures to form during development and is required for embryonic growth and survival. The four-chambered mammalian heart arises from a series of complex processes during embryonic development that includes the specification and differentiation of the different cardiac cell types within the heart, proliferation, and morphological movements of the early heart fields. Early development of the heart is governed by hyperplastic growth in which cardiac cells undergo mitogen- dependent activation during the G1-phase of the cell cycle. Though numerous growth factor signals have been shown to be required for cardiomyocyte proliferation, genetic studies have only identified a limited number of transcription factors that act to regulate the entry of cardiomyocytes into S-phase. Casz1 is an evolutionarily conserved transcription factor that is essential for heart development; however, there are vast deficiencies in our understanding of the mechanism by which Casz1 regulates aspects of cardiac development. Here we report that Casz1 is expressed in, and gives rise to, cardiomyocytes in the first and second heart fields. -

Program Book

The Genetics Society of America Conferences 15th International Xenopus Conference August 24-28, 2014 • Pacific Grove, CA PROGRAM GUIDE LEGEND Information/Guest Check-In Disabled Parking E EV Charging Station V Beverage Vending Machine N S Ice Machine Julia Morgan Historic Building W Roadway Pedestrian Pathway Outdoor Group Activity Area Program and Abstracts Meeting Organizers Carole LaBonne, Northwestern University John Wallingford, University of Texas at Austin Organizing Committee: Julie Baker, Stanford Univ Chris Field, Harvard Medical School Carmen Domingo, San Francisco State Univ Anna Philpott, Univ of Cambridge 9650 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20814-3998 Telephone: (301) 634-7300 • Fax: (301) 634-7079 E-mail: [email protected] • Web site: genetics-gsa.org Thank You to the Following Companies for their Generous Support Platinum Sponsor Gold Sponsors Additional Support Provided by: Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC Monterey Convention & Gene Tools, LLC Visitors Bureau Leica Microsystems Xenopus Express 2 Table of Contents General Information ........................................................................................................................... 5 Schedule of Events ............................................................................................................................. 6 Exhibitors ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Opening Session and Plenary/Platform Sessions ............................................................................ -

Long Non-Coding RNA Containing Ultraconserved Genomic Region 8 Promotes Bladder Cancer Tumorigenesis

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 15 Long non-coding RNA containing ultraconserved genomic region 8 promotes bladder cancer tumorigenesis Michele Olivieri1,*, Matteo Ferro2,*, Sara Terreri1,*, Montano Durso1,3, Alessandra Romanelli4, Concetta Avitabile4, Ottavio De Cobelli2, Anna Messere5, Dario Bruzzese6, Ivan Vannini7, Luciana Marinelli4, Ettore Novellino4, Wei Zhang8, Mariarosaria Incoronato9, Gennaro Ilardi10, Stefania Staibano10, Laura Marra11, Renato Franco12, Sisto Perdonà11, Daniela Terracciano13, Bogdan Czerniak8, Giovanna L. Liguori1, Vincenza Colonna1, Muller Fabbri14, Ferdinando Febbraio15, George A. Calin16,*, Amelia Cimmino1,* 1Institute of Genetics and Biophysics “A. Buzzati Traverso”, National Research Council (CNR), Naples, Italy 2Division of Urology, European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy 3Bio-Ker S.r.l. MultiMedica S.p.A. Naples, Italy 4Department of Pharmacy, University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, Italy 5 Department of Environmental, Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, Second University of Naples, Naples, Italy 6Department of Public Health, University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, Italy 7Istituto Scientifico Romagnolo per lo Studio e la Cura dei Tumori (IRST) S.r.l. IRCCS, Gene Therapy Unit, Meldola, Italy 8Department of Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA 9Fondazione IRCCS SDN, Naples, Italy 10Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, Italy 11Division of Urology, IRCS -

Prrxl1 and Casz1 Transcriptional Regulation in the Development of the DRG-Spinal Nociceptive Circuitry

Doutoramento NEUROCIÊNCIAS Prrxl1 and Casz1 transcriptional regulation in the development of the DRG-spinal nociceptive circuitry César Bruno Cunha Monteiro D 2016 Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto para candidatura ao grau de Doutor no âmbito do Programa Doutoral em Neurociências. O candidato realizou o presente trabalho com o apoio de uma Bolsa de Investigação concedida pela Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, com a referência SFRH/BD/77621/2011, financiada pelo POPH – QREN – Tipologia 4.1 – Formação Avançada, comparticipado pelo Fundo Social Europeu e por fundos nacionais do MEC. Orientação: Professora Doutora Deolinda Maria Alves de Lima (Universidade do Porto, Portugal) Co-orientação: Filipe Almeida Monteiro (Universidade do Porto, Portugal) Artigo 48º, parágrafo 3: “A Faculdade não responde pelas doutrinas expendidas na dissertação” Regulamento da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto Decreto-Lei nº 19337 de 29 de Janeiro de 1931 CORPO CATEDRÁTICO DA DACULDADE DE MEDICINA DO PORTO Professores Efetivos Professores Jubilados/Aposentados Alberto Manuel Barros da Silva Abel Vitorino Trigo Cabral Altamiro Manuel Rodrigues Costa Pereira Alexandre Alberto Guerra Sousa Pinto António Albino Coelho Marques Abrantes Álvaro Jerónimo Leal Machado de Aguiar Teixeira Amândio Gomes Sampaio Tavares Daniel Filipe Lima Moura António Augusto Lopes Vaz Deolinda Maria Valente Alves Lima Teixeira António Carlos Freitas Ribeiro Saraiva Francisco Fernando Rocha Gonçalves António Carvalho Almeida Coimbra -

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS of a CASZ1/CHD5 INTERACTION in CARDIAC DEVELOPMENT and DISEASE Stephen Sojka a Dissertation Submitted To

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF A CASZ1/CHD5 INTERACTION IN CARDIAC DEVELOPMENT AND DISEAS E Stephen Sojka A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Frank Conlon Stephen Crews A. Greg Matera Mark Peifer William Marzluff © 2014 Stephen Sojka ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT STEPHEN P. SOJKA: Functional analysis of a CASZ1/CHD5 interaction in cardiac development and disease (Under the direction of Frank L. Conlon) Early cardiac development involves coordination of a number of processes including the specification and differentiation of cardiomyocytes, the ventral migration of cardiac cell populations, the formation of a linear heart tube, and the subsequent morphogenic movements required for cardiac looping and chamber formation. These early processes require the precise spatial and temporal regulation of a number of genetic pathways, which coordinate the activation and repression of various cardiac-specific transcription factors and their targets. These transcription factors are in part regulated by the formation of transcriptional complexes via interaction with regionally expressed cofactors. In this dissertation, I explore the role of protein- protein interactions in regulating the novel para zinc finger transcription factor CASTOR (CASZ1). We carried out a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify cardiac specific CASZ1 interacting partners and identified congenital heart disease protein 5 (CHD5), a small coiled coil protein expressed within the putative critical region of chromosome 21 associated with congenital heart disease in Down syndrome patients. We observe that CASZ1 and CHD5 co-localize in the nuclei of cardiomyocytes and interact in vivo. -

DNA Methylation and Smoking in Korean Adults: Epigenome-Wide Association Study Mi Kyeong Lee1,2,3, Yoonki Hong3, Sun-Young Kim4, Stephanie J

Lee et al. Clinical Epigenetics (2016) 8:103 DOI 10.1186/s13148-016-0266-6 RESEARCH Open Access DNA methylation and smoking in Korean adults: epigenome-wide association study Mi Kyeong Lee1,2,3, Yoonki Hong3, Sun-Young Kim4, Stephanie J. London1*† and Woo Jin Kim3*† Abstract Background: Exposure to cigarette smoking can increase the risk of cancers and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases. However, the underlying mechanisms of how smoking contributes to disease risks are not completely understood. Epigenome-wide association studies (EWASs), mostly in non-Asian populations, have been conducted to identify smoking-associated methylation alterations at individual probes. There are few data on regional methylation changes in relation to smoking. Few data link differential methylation in blood to differential gene expression in lung tissue. Results: We identified 108 significant (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) differentially methylated probes (DMPs) and 87 significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) (multiple-testing corrected p < 0.01) in current compared to never smokers from our EWAS of cotinine-validated smoking in blood DNA from a Korean chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort (n = 100 including 31 current, 30 former, and 39 never smokers) using Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. Of the 108 DMPs (FDR < 0.05), nine CpGs were statistically significant based on Bonferroni correction and 93 were novel including five that mapped to loci previously associated with smoking. Of the 87 DMRs, 66 were mapped to novel loci. Methylation correlated with urine cotinine levels in current smokers at six DMPs, with pack-years in current smokers at six DMPs, and with duration of smoking cessation in former smokers at eight DMPs. -

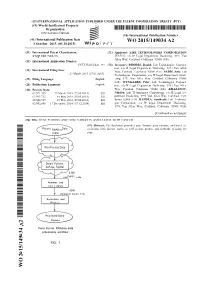

WO 2015/149034 A2 1 October 2015 (01.10.2015) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/149034 A2 1 October 2015 (01.10.2015) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (71) Applicant: LIFE TECHNOLOGIES CORPORATION C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) [US/US]; c/o IP Legal Department Docketing, 5791 Van Allen Way, Carlsbad, California 92008 (US). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US2015/023 197 (72) Inventors: RHODES, Daniel; Life Technologies Corpora tion, c/o IP Legal Department Docketing, 579 1 Van Allen (22) International Filing Date: Way, Carlsbad, California 92008 (US). SADIS, Seth; Life 27 March 2015 (27.03.2015) Technologies Corporation, c/o IP Legal Department Dock (25) Filing Language: English eting, 5791 Van Allen Way, Carlsbad, California 92008 (US). WYNGAARD, Peter; Life Technologies Corpora (26) Publication Language: English tion, c/o IP Legal Department Docketing, 579 1 Van Allen (30) Priority Data: Way, Carlsbad, California 92008 (US). KHAZANOV, 61/971,455 27 March 2014 (27.03.2014) US Nikolay; Life Technologies Corporation, c/o IP Legal De 61/993,732 15 May 2014 (15.05.2014) US partment Docketing, 5791 Van Allen Way, Carlsbad, Cali 62/004,727 29 May 2014 (29.05.2014) us fornia 92008 (US). BANDLA, Santhoshi; Life Technolo 62/092,898 17 December 2014 (17. 12.2014) us gies Corporation, c/o IP Legal Department Docketing, 5791 Van Allen Way, Carlsbad, California 92008 (US). [Continued on nextpage] (54) Title: GENE FUSIONS AND GENE VARIANTS ASSOCIATED WITH CANCER (57) Abstract: The disclosure provides gene fusions, gene variants, and novel as RNASeq sociations with disease states, as well as kits, probes, and methods of using the (.bam) same. -

Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify Genetic Loci Associated With

Page 1 of 86 Diabetes Genome-wide Association Studies Identify Genetic Loci Associated with Albuminuria in Diabetes Alexander Teumer1,2*, Adrienne Tin3*, Rossella Sorice4*, Mathias Gorski5,6*, Nan Cher Yeo7*, Audrey Y. Chu8,9, Man Li3, Yong Li10, Vladan Mijatovic11, Yi-An Ko12, Daniel Taliun13, Alessandro Luciani14, Ming-Huei Chen15,16, Qiong Yang16, Meredith C. Foster17, Matthias Olden5,18, Linda T. Hiraki19, Bamidele O. Tayo20, Christian Fuchsberger13, Aida Karina Dieffenbach21,22, Alan R. Shuldiner23, Albert V. Smith24,25, Allison M. Zappa26, Antonio Lupo27, Barbara Kollerits28, Belen Ponte29, Bénédicte Stengel30,31, Bernhard K. Krämer32, Bernhard Paulweber33, Braxton D. Mitchell23, Caroline Hayward34, Catherine Helmer35, Christa Meisinger36, Christian Gieger37, Christian M. Shaffer38, Christian Müller39,40, Claudia Langenberg41, Daniel Ackermann42, David Siscovick43, DCCT/EDIC44, Eric Boerwinkle45, Florian Kronenberg28, Georg B. Ehret46, Georg Homuth47, Gerard Waeber48, Gerjan Navis49, Giovanni Gambaro50, Giovanni Malerba11, Gudny Eiriksdottir24, Guo Li43, H. Erich Wichmann51-53, Harald Grallert36,54,55, Henri Wallaschofski56, Henry Völzke1,2, Herrmann Brenner57, Holly Kramer20, I. Mateo Leach58, Igor Rudan59, J.L. Hillege60, Jacques S. Beckmann61,62, Jean Charles Lambert63, Jian'an Luan41, Jing Hua Zhao41, John Chalmers64, Josef Coresh3,65, Joshua C. Denny66, Katja Butterbach57, Lenore J. Launer67, Luigi Ferrucci68, Lyudmyla Kedenko33, Margot Haun28, Marie Metzger30,31, Mark Woodward3,64,69, Matthew J. Hoffman7, Matthias Nauck2,56, Melanie Waldenberger36, Menno Pruijm70, Murielle Bochud71, Myriam Rheinberger72, N. Verweij58, Nicholas J. Wareham41, Nicole Endlich73, Nicole Soranzo74,75, Ozren Polasek76, P. van der Harst60, Peter Paul Pramstaller13, Peter Vollenweider48, Philipp S. Wild77-79, R.T. Gansevoort60, Rainer Rettig80, Reiner Biffar81, Robert J. Carroll66, Ronit Katz82, Ruth J.F. Loos41,83, Shih-Jen Hwang9, Stefan Coassin28, Sven Bergmann84, Sylvia E. -

Lncrna DRAIR Is Downregulated in Diabetic Monocytes and Modulates Inflammatory Phenotype Via Epigenetic Mechanisms

Supplementary Material LncRNA DRAIR is downregulated in diabetic monocytes and modulates inflammatory phenotype via epigenetic mechanisms Marpadga A. Reddy, Vishnu Amaram, Sadhan Das, Vinay Singh Tanwar, Rituparna Ganguly, Mei Wang, Linda Lanting, Lingxiao Zhang, Maryam Abdollahi, Zhuo Chen, Xiwei Wu, Sridevi Devaraj and Rama Natarajan Supplementary Figure. 1. (A) RNA-seq data showing inflammatory genes upregulated in monocytes from humans with type 2 diabetes versus controls. (B-C) Bubble plots depicting GO Processes enriched in upregulated and downregulated genes. Bubble color represents significance (p-values), and bubble size indicates gene count. (D-E) IPA analysis showing Diseases & Functions enriched in upregulated (D) and downregulated genes (E). (F) IPA analysis showing Canonical pathways enriched in upregulated genes. (G) IPA analysis showing 2 Overlapping Canonical pathways in downregulated genes. Numbers indicate common genes in overlapping networks. SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. In panels D and F, y-axis represents –log(p-values) from Fisher’s exact test. In panel E, y-axis shows Z-score, where 2 is set as threshold. 3 Supplementary Figure. 2. (A-B) GO Biological processes enriched among differentially expressed gene (DEG)s located nearby the downregulated (A) and upregulated (B) lncRNAs in T2D. DEGs nearby differentially expressed lncRNAs ( 250 kb) in T2D were analyzed using the web-based gene list enrichment analysis tool Enrichr (1-2). 4 Supplementary Figure 3. Characterization of DRAIR coding potential. (A) The Raw PhyloCSF tracks of DRAIR genomic regions, showing the PhyloCSF score of less than zero in all six reading frames, predicting that DRAIR lacks coding potential. In addition, Coding Potential Calculator 2 (CPC2) software (3) also predicted that DRAIR lacks coding potential (coding probability 0.0302545). -

CASZ1, a Candidate Tumor-Suppressor Gene, Suppresses Neuroblastoma Tumor Growth Through Reprogramming Gene Expression

Cell Death and Differentiation (2011) 18, 1174–1183 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1350-9047/11 www.nature.com/cdd CASZ1, a candidate tumor-suppressor gene, suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth through reprogramming gene expression Z Liu1,6, X Yang1,6,ZLi1, C McMahon1, C Sizer1, L Barenboim-Stapleton2, V Bliskovsky3, B Mock3, T Ried2, WB London4, J Maris5, J Khan1 and CJ Thiele*,1 Neuroblastoma (NB) is a common childhood malignant tumor of the neural crest-derived sympathetic nervous system. In NB the frequent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosome 1p raises the possibility that this region contains tumor-suppressor genes whose inactivation contributes to tumorigenesis. The human homolog of the Drosophila neural fate determination gene CASZ1, a zinc-finger transcription factor, maps to chromosome 1p36.22, a region implicated in NB tumorigenesis. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that low-CASZ1 expression is significantly correlated with increased age (Z18 months), Children’s Oncology Group high-risk classification, 1p LOH and MYCN amplification (all Po0.0002) and decreased survival probability (P ¼ 0.0009). CASZ1 was more highly expressed in NB with a differentiated histopathology (Po0.0001). Retinoids and epigenetic modification agents associated with regulation of differentiation induced CASZ1 expression. Expression profiling analysis revealed that CASZ1 regulates the expression of genes involved in regulation of cell growth and developmental processes. Specific restoration of CASZ1 in NB cells induced cell differentiation, enhanced cell adhesion, inhibited migration and suppressed tumorigenicity. These data are consistent with CASZ1 being a critical modulator of neural cell development, and that somatically acquired disruption of normal CASZ1 expression contributes to the malignant phenotype of human NB. -

Downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO

Lim et al. Clinical Epigenetics (2019) 11:180 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0756-4 RESEARCH Open Access Epigenome-wide base-resolution profiling of DNA methylation in chorionic villi of fetuses with Down syndrome by methyl- capture sequencing Ji Hyae Lim1,2, Yu-Jung Kang1, Bom Yi Lee3, You Jung Han4, Jin Hoon Chung4, Moon Young Kim4, Min Hyoung Kim5, Jin Woo Kim6, Youl-Hee Cho2* and Hyun Mee Ryu1,7* Abstract Background: Epigenetic mechanisms provide an interface between environmental factors and the genome and are influential in various diseases. These mechanisms, including DNA methylation, influence the regulation of development, differentiation, and establishment of cellular identity. Here, we performed high-throughput methylome profiling to determine whether differential patterns of DNA methylation correlate with Down syndrome (DS). Materials and methods: We extracted DNA from the chorionic villi cells of five normal and five DS fetuses at the early developmental stage (12–13 weeks of gestation). Methyl-capture sequencing (MC-Seq) was used to investigate the methylation levels of CpG sites distributed across the whole genome to identify differentially methylated CpG sites (DMCs) and regions (DMRs) in DS. New functional annotations of DMR genes using bioinformatics tools were predicted. Results: DNA hypermethylation was observed in DS fetal chorionic villi cells. Significant differences were evident for 4,439 DMCs, including hypermethylation (n = 4,261) and hypomethylation (n = 178). Among them, 140 hypermethylated DMRs and only 1 hypomethylated DMR were located on 121 genes and 1 gene, respectively. One hundred twenty-two genes, including 141 DMRs, were associated with heart morphogenesis and development of the ear, thyroid gland, and nervous systems.