The Historic New Orleans Quarterly, Volume XXVII, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of New Orleans Residential Parking Permit (Rpp) Zones

DELGADO CITY PARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE FAIR GROUNDS ZONE 17 RACE COURSE ZONE 12 CITY OF NEW ORLEANS RESIDENTIAL PARKING E L Y PERMIT (RPP) ZONES S 10 I ¨¦§ A ES N RPP Zones Boundary Descriptions: PL F A I N E Zone 1: Yellow (Coliseum Square) AD L E D St. Charles Avenue / Pontchartrain Expwy / S AV Mississippi River / Jackson Avenue A T V S Zone 2: Purple (French Quarter) D North Rampart Street / Esplanade Avenue / A Mississippi River / Iberville Street O R TU B LA Zone 3: Blue NE ZONE 11 South Claiborne Avenue / State Street / V AV Willow Street / Broadway Street A C N AN O AL Zone 4: Red (Upper Audubon) T S LL T St. Charles Avenue / Audubon Street / O Leake Avenue / Cherokee Street R R A 10 Zone 5: Orange (Garden District) C ¨¦§ . S St. Charles Avenue / Jackson Avenue / ZONE 2 Constance Street / Louisiana Avenue Zone 6: Pink (Newcomb Blvd/Maple Area) Willow Street / Tulane University / St. Charles Avenue / South Carrollton Avenue Zone 7: Brown (University) Willow Street / State Street / St. Charles Avenue / Calhoun Street / Loyola University ZONE 18 Zone 9: Gold (Touro Bouligny) ZONE 14 St. Charles Avenue / Louisiana Avenue / Magazine Street / Napoleon Avenue ZONE 3 AV Zone 10: Green (Nashville) NE St. Charles Avenue / Arabella Street / ZONE 6 OR Prytania Street / Exposition Blvd IB LA C Zone 11: Raspberry (Faubourg Marigny) S. TULANE St. Claude Avenue / Elysian Fields Avenue / UNIVERSITY ZONE 16 Mississippi River / Esplanade Avenue ZONE 15 Zone 12: White (Faubourg St. John) DeSaix Blvd / St. Bernard Avenue / LOYOLA N North Broad Street / Ursulines Avenue / R UNIVERSITY A Bell Street / Delgado Drive ZONE 7 P O E L Zone 13: Light Green (Elmwood) E AV ZONE 1 Westbank Expwy / Marr Avenue / O ES V General de Gaulle Drive / Florence Avenue / N L ZONE 4 R Donner Road A HA I V . -

UPM-Catalog-Fall-2020.Pdf

N I V E R S I U T Y P R E S S O Books for Fall–Winter 2020–2021 F M I I S P S P I I S S N I V E R S I CONTENTS U T Y P R 3 Alabama Quilts ✦ Huff / King E 9 The Amazing Jimmi Mayes ✦ Mayes / Speek S ✦ S 9 Big Jim Eastland Annis ✦ O 27 Bohemian New Orleans Weddle F 32 Breaking the Blockade ✦ Ross M ✦ I 5 Can’t Be Faded Stooges Brass Band / DeCoste I S P S P I I S S 2 Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! ✦ Stone 33 Chaos and Compromise ✦ Pugh 23 Chocolate Surrealism ✦ Njoroge 7 City Son ✦ Dawkins OUR MISSION 12 Cold War II ✦ Prorokova-Konrad University Press of Mississippi (UPM) tells stories 31 The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume III ✦ Haney / Forrester of scholarly and social importance that impact our 18 Conversations with Dana Gioia ✦ Zheng 19 Conversations with Jay Parini ✦ Lackey state, region, nation, and world. We are commit- 19 Conversations with John Berryman ✦ Hoffman ted to equality, inclusivity, and diversity. Working 18 Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry ✦ Godfrey at the forefront of publishing and cultural trends, 21 Critical Directions in Comics Studies ✦ Giddens we publish books that enhance and extend the 8 Crooked Snake ✦ Boteler 22 Damaged ✦ Rapport reputation of our state and its universities. 10 Dan Duryea ✦ Peros Founded in 1970, the University Press of 7 Emanuel Celler ✦ Dawkins Mississippi turns fifty in 2020, and we are proud 30 Folklore Recycled ✦ de Caro of our accomplishments. -

Pdf2019.04.08 Fontana V. City of New Orleans.Pdf

Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LUKE FONTANA, Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO.: v. JUDGE: The CITY OF NEW ORLEANS; MAYOR LATOYA CANTRELL, in her official capacity; MICHAEL HARRISON, FORMER MAGISTRATE JUDGE: SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; SHAUN FERGUSON, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; and NEW ORLEANS POLICE OFFICERS BARRY SCHECHTER, SIDNEY JACKSON, JR. and ANTHONY BAKEWELL, in their official capacities, Defendants. COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. For more than five years, the City of New Orleans (the “City”) has engaged in an effort to stymie free speech in public spaces termed “clean zones.” Beginning with the 2013 Super Bowl, the City has enacted zoning ordinances to temporarily create such “clean zones” in which permits, advertising, business transactions, and commercial activity are strictly prohibited. Clean zones have been enacted for various public events including the 1 Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 2 of 16 Superbowl, French Quarter Festival, Satchmo Festival and Essence Festival. These zones effectively outlaw the freedom of expression in an effort to protect certain private economic interests. The New Orleans Police Department (“NOPD”) enforces the City’s “clean zones” by arresting persons engaged in public speech perceived as inimical to those interests. 2. During the French Quarter Festival in April 2018, Plaintiff Luke Fontana was doing what he has done for several years: standing behind a display table on the Moonwalk near Jax Brewery by the Mississippi riverfront. -

The Old and the Neutral the Mile-Long Crescent Park in New Orleans Shows Ambitions Meeting Reality

THE OLD AND THE NEUTRAL THE MILE-LONG CRESCENT PARK IN NEW ORLEANS SHOWS AMBITIONS MEETING REALITY. BY JOHN KING, HONORARY ASLA MANDEVILLE WHARF An elliptical lawn marks the heart of Crescent Park, part of an ambitious project intended to revitalize a rough industrial edge of the Mississippi River in New Orleans. TIMOTHY HURSLEY TIMOTHY 80 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JULY 2018 LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JULY 2018 / 81 N A LANGUID FRIDAY floodwall roughly 10 feet high as well afternoon in New Orleans, as railbeds where freight cars might the sounds of the French Quar- sit for days between journeys. The Oter Festival spill downriver toward stylized promenade is promoted by Crescent Park. The music is loudest at some as New Orleans’s answer to Mil- the park’s Mandeville Wharf, but the lennium Park or the High Line, one dozen or so visitors seem to pay no with a photogenic bridge designed by notice as they lounge on a raised lawn the architect David Adjaye. Its impact next to remnants of a vast storage on the adjacent Bywater neighbor- shed, or ride scooters in the shade cast hood, where small colorful houses by the new corrugated roof, or lean line streets where the sidewalks come against galvanized steel guardrails and go, can be seen in the condo com- TOP to watch a barge plow through the plexes starting to rise along its edge. The industrial heritage dark waters. Nor can the distant din of the riverfront seen compete with the cries of the seagulls Viewed through a wider lens, Cres- in this 1950s photo is retained in the who have claimed a fenced-off stretch cent Park fits within the constellation forms and materials of the wharf as their own. -

Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans. Michael Eugene Crutcher Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Crutcher, Michael Eugene Jr, "Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 272. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/272 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Banquettes and Baguettes

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Banquettes and Baguettes “In the city’s early days, city blocks were called islands, and they were islands with little banks around them. Logically, the French called the footpaths on the banks, banquettes; and sidewalks are still so called in New Orleans,” wrote John Chase in his immensely entertaining history, “Frenchmen, Desire Good Children…and Other Streets of New Orleans!” This was mostly true in 1949, when Chase’s book was first published, but the word is used less and less today. In A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People by Jay Dearborn Edwards and Nicolas Kariouk Pecquet du Bellay de Verton, one learns that, in New Orleans (instead of the French word trottoir for sidewalk), banquette is used. New Orleans’ historic “banquette cottage (or Creole cottage) is a small single-story house constructed flush with the sidewalk.” According to the authors, “In New Orleans the word banquette (Dim of banc, bench) ‘was applied to the benches that the Creoles of New Orleans placed along the sidewalks, and used in the evenings.’” This is a bit different from Chase’s explanation. Although most New Orleans natives today say sidewalks instead of banquettes, a 2010 article in the Time-Picayune posited that an insider’s knowledge of New Orleans’ time-honored jargon was an important “cultural connection to the city”. The article related how newly sworn-in New Orleans police superintendent, Ronal Serpas, “took pains to re-establish his Big Easy cred.” In his address, Serpas “showed that he's still got a handle on local vernacular, recalling how his grandparents often instructed him to ‘go play on the neutral ground or walk along the banquette.’” A French loan word, it comes to us from the Provençal banqueta, the diminutive of banca, meaning bench or counter, of Germanic origin. -

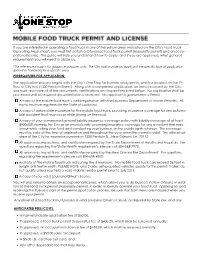

If You Are Interested in Operating a Food Truck in Any of the Yellow Areas

If you are interested in operating a food truck in any of the yellow areas indicated on the City’s Food Truck Operating Areas map*, you must first obtain a City-issued food truck permit (mayoralty permit) and an occu- pational license. This guide will help you understand how to apply, and if you are approved, what general requirements you will need to abide by. *The referenced map is for guidance purposes only. The City shall provide an applicant the specific type of application (permit or franchise) for a specific area. PREREQUISITES FOR APPLICATION: The application process begins with the City’s One Stop for licenses and permits, which is located on the 7th floor of City Hall (1300 Perdido Street). Along with a completed application, on forms provided by the City, you must also have all of the documents, certifications and inspections listed below. No application shall be processed until all required documentation is received. No applicant is guaranteed a Permit. A copy of the mobile food truck’s valid registration with the Louisiana Department of Motor Vehicles. All trucks must be registered in the State of Louisiana. A copy of automobile insurance for the mobile food truck, providing insurance coverage for any automo- bile accident that may occur while driving on the road. A copy of your commercial general liability insurance coverage policy with liability coverage of at least $500,000, naming the City as an insured party, providing insurance coverage for any accident that may occur while selling your food and conducting your business on the public rights-of-ways. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

So Many Italians Lived in the French Quarter in the Early

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED On March 14, 1891, 1718 ~ 2018 a mob of New Orleans citizens charged the parish prison and shot 300 nine and lynched TRICENTENNIAL two Italians. COURTESY BROCATO’S KNOWLA There were so many Italians living and working in After New Orleans Po- the French lice Chief David Hen- Quarter that nessey was allegedly it earned the assassinated by the name Little Italian mafia, a group Palermo.’ Angelo Brocato opened his first of citizens lynched storefront in the 500 block of Ursulines and killed 11 Italians. Street where Italians would come every Between 1850 and 1870, New Orleans had the largest The incident strained morning for lemon ice. Italian-born population in the United States. relations between the THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS U.S. and Italy. So many Italians lived in the French Quarter in the early 20th century, the Vieux Carré earned the nicknames “Little Italy” and “Little Palermo” for the number of Italians, and more specifically, Sicilians, who lived there., Between 1880 and 1910 the state brought After Hennessey’s murder, 19 Italians hundreds of Italian men from Naples, Tri- were arrested. Six of the men were acquitted THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION este and Palermo to replace the African- following the first trial, and many in the city American laborers went mad with outrage after the Civil War. at what they felt was The Italian population injustice. On March 14, flourished in the fol- 1891, a mob charged the lowing years, as many parish prison, shot nine became merchants and lynched two others and entrepreneurs. -

French Quarter Night Life

51 23 67 62 17 69 71 26 11 32 33 22 1 25 4 30 41 28 52 10 27 15 43 7 2 14 8 9 40 65 58 50 63 39 73 56 35 48 60 6853 31 74 24 47 61 55 59 13 66 42 72 29 64 54 36 49 45 19 12 5 21 18 57 38 44 46 3 6 70 16 37 34 20 French Quarter Night Life 1. Bombay Club 9. Bourbon Street Blues Company 17. Cocina 25. Erin Rose 33. Good Friends Bar 41. Le Roundup 830 Conti Street 441 Bourbon Street 1201 Burgundy Street 811 Conti Street 740 Dauphine Street 819 St. Louis Street New Orleans, LA 70112 New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70116 New Orleans, LA 70112 New Orleans, LA 70116 New Orleans, LA 70116 504-588-0972 504-566-1507 504-522-9715 504-299-8496 504-566-7191 504-561-8340 2. 735 Nightclub and Bar 10. Cafe Beignet 18. Coop's Place 26. Fahy's Irish Pub 34. Hard Rock Cafe 42. Lucille's Golden Lantern 735 Bourbon Street 311 Bourbon Street 1109 Decatur Street 540 Burgundy Street 418 N. Peters Street 1239 Royal Street New Orleans, LA 70116 New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70112 New Orleans, LA 70112 New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70116 504-581-6740 504-525-2611 504-525-9053 504-586-9806 504-529-5617 504-529-2860 3. The Abbey 11. Cafe Lafitte In Exile 19. Corner Oyster Bar & Grill 27. The Famous Door 35. -

New Marigny” GMAC Cingular Wireless Verizon Wireless Sprint/Sprint PCS Tion of I-10 Over a Main 1831 Pontchartrain Railroad (A.K.A

Annual Neighborhood Events • August: Night Out Against Crime LIVING WITH HISTORY • October: Preservation Resource Center’s IN NEW ORLEANS’ NEIGHBORHOODS Rebuilding Together program Neighborhood Organizations eeww • Crescent City Peace Alliance NN • Faubourg Franklin Foundation rriiggnnyy • Faubourg St. Roch Improvement Association MMaa onvenient to both New Orleans’ Central 1798 Pierre Philippe de Marigny acquires Business District and the Vieux Carré, historic New Dubreuil Plantation Circle Food Store 1800 Marquis Antoine Xavier Bernard 1522 St. Bernard Avenue Marigny, also called Faubourg St. Roch, has all the Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville A TRADITION IN NEW ORLEANS makings of a desirable inherits from Pierre Philippe de Marigny We are still here and still serving the community. C downtown neighbor- 1803 Louisiana Purchase Saving You Money on Groceries 1806 Nicholas de Finiels develops street Services, Bill Payments hood. Industrialization plan for Marigny; engineer Barthelemy BellSouth • Entergy • Sewer & Water Board and flight to the suburbs Lafon contracts to lay out the street grid We Accept Payment For: hit this area hard, how- 1810 Marigny extends original subdivision, American Express E Mobil (formerly Voicestream) MCI/MCI Worldcom Wireless Ford Motor Credit asking Lafon to plot area now known Chevron Toyota Financial Services Shell Gas Card Macy’s ever, and the construc- Discover Card AT & T Target Visa Card Sam’s Club as “New Marigny” GMAC Cingular Wireless Verizon Wireless Sprint/Sprint PCS tion of I-10 over a main 1831 Pontchartrain Railroad (a.k.a. “Smoky Mervyn’s Dish Network Capital One Credit Card Texaco Sears JC Penney Dillard’s Wal-Mart thoroughfare in the Mary”), 2nd oldest railroad in U.S., opens on Elysian Fields 1960s sent many resi- 1832 World’s largest cotton press opens on dents and businesses present Press Street packing. -

Press Street: a Concept for Preserving, Reintroducing and Fostering Local History Brian J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history Brian J. McBride Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation McBride, Brian J., "Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2952. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2952 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESS STREET: A CONCEPT FOR PRESERVING, REINTRODUCING, AND FOSTERING LOCAL HISTORY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in The School of Landscape Architecture by Brian J. McBride B.S., Louisiana State University, 1994 May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to recognize a number of people for providing assistance, insight and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis. Special thanks to the faculty and staff of the School of Landscape Architecture, especially to Max Conrad, Van Cox and Kevin Risk. To all without whom I could not have completed this process, especially my parents for their persistence; and my wife, for her continued love and support.