Folklore in New World Black Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Tricksters in African American and Chinese American Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction Crystal Suzette anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Ethnic Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Crystal Suzette, "Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623988. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-z7mp-ce69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Edgar Mittelholzer Memorial Lectures

BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Edited and with an Introduction by Andrew O. Lindsay 1 Edited by Andrew O. Lindsay BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES - VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Preface © Andrew Jefferson-Miles, 2014 Introduction © Andrew O. Lindsay, 2014 Cover design by Peepal Tree Press Cover photograph: Courtesy of Jacqueline Ward All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-67-6 2 Contents: Tenth Series, 1986: The Arawak Language in Guyanese Culture by John Peter Bennett FOREWORD by Denis Williams .......................................... 3 PREFACE ................................................................................. 5 THE NAMING OF COASTAL GUYANA .......................... 7 ARAWAK SUBSISTENCE AND GUYANESE CULTURE ........................................................................ 14 Eleventh Series, 1987. The Relevance of Myth by George P. Mentore PREFACE ............................................................................... 27 MYTHIC DISCOURSE......................................................... 29 SOCIETY IN SHODEWIKE ................................................ 35 THE SELF CONSTRUCTED ............................................... 43 REFERENCES ....................................................................... 51 Twelfth Series, 1997: Language and National Unity by Richard Allsopp CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD -

An Exploration of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Post-Soul Speculation: An Exploration Of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction Hilary Word Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Word, Hilary, "Post-Soul Speculation: An Exploration Of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1817. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1817 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-SOUL SPECULATION: AN EXPLORATION OF AFRO-SOUTHERN SPECULATIVE FICTION A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by HILARY M. WORD May 2020 Copyright © Hilary M. Word 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of female authored, post-soul, Afro-Southern speculative fiction. The specific texts being examined are My Soul to Keep by Tananarive Due, Stigmata by Phyllis Alesia Perry, and Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward. Through exploration of these texts, I posit two large arguments. First, I posit that this thesis as a collective work illustrates how women-authored Afro-Southern speculative fiction based in the post-soul era embodies and champions womanist politics and praxis critical for liberation through speculative elements. Second, I assert that this thesis is demonstrative of how this particular type of fiction showcases the importance of specificity of setting and reflects other, often erased facets of African American identity and realities by centering the experiences of contemporary Black Southerners. -

Art of Wilson Harris

THE ART OF WILSON HARRIS BY MMilON C. GILLILMD A DI.^SERTATIOi:! PRESENTED TO ItlE G.R.\DUATE COUNCII OE TEE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFI1.LMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGR.ee OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LT^TIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1982 Copyright 19B2 by Marion Charlotte Gilliland TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Introduction The Visionary Art of \vilson Harris 1 N otes 14 Part I Contexts of Vision Chapter 1 An Overview of the Fiction 17 Notes 35 Chapter 2 Wilson Harris in the West Indian Context 37 Notes 60 Chapter 3 The Role of Imaginaticn in Creativity 63 Notes 78 Chapter 4 Three Structuring Ideas in Wilson Harris's Fiction 81 Notes 115 Part II Visionary Texts Chapter 5 Companioas of the Day and Night 119 Note s ' 133 Chapter 6 Da Silva da Silva's Cultivated Wilderness , . 134 Notes 154 Chapter 7 Genesis of the Clowns 155 Notes c . 170 Chapter 8 The Tree of the Sun 171 Note 184 Appendix Three Interviews with Wilson Harris Synchrcnlcity 186 Shamanisiu 205 The Eye of the Scarecrow 227 Bibliography 244 Biographical Sketch 260 Xll Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE ART OF WILSON HARRIS By Marion C. Gilliland December 1982 Chairman: Alistair M. Duckworth Major Department: English Wilson Harris, the Guyanese novelist, critic and poet, seeks to create new forms in the novel which will reflect his vision of the basic unity of man. This unity is free of cultural and racial ties, embodies a new state of consciousness, healed rather than divided, and is open to greater possibilities of human fulfillment for all men. -

Adam Floridia, Middlesex Community College

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Spring/Summer 2010 (3:3/4) Unconsciously Completing the Canon: An Argument for The Original of Laura Adam Floridia, Middlesex Community College Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Nabokov’s prolific career— spanning six decades and numerous languages—is the fact that there is surprisingly remarkable consistency to his canon. The casual Nabokov reader will certainly notice the leitmotifs of chess, light and color, lepidoptery and various word games; the more acute Nabokov scholar, however, will note a theme, at times obvious, at times latent, always pulsing beneath the surface of his stories. Operating as the life force of his literature, sometimes this particular theme becomes obvious to both readers and characters alike, for example when all of Krug’s emotional anguish is lifted at the end of Bend Sinister thanks to the epiphany that he is merely a character. Krug’s epiphany, the overriding concern of all of Nabokov’s work, is the concept of consciousness. In Speak, Memory Nabokov begins, “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”1 It is this mystery of the relatively brief moment of consciousness that is one’s life that so harasses and fascinates the author and so informs his writing. He continues, “Over and over again my mind has made colossal efforts to distinguish the faintest of 1 Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Spring/Summer 2010 (3:3/4) personal glimmers in the impersonal darkness on both sides of my life”1 and concedes, “Initially, I was unaware that time, so boundless at first blush, was a prison.”2 It was early in his own life that Nabokov came to this realization that life is a mere flickering of consciousness between the vast, dark voids at both ends of a human’s time on earth. -

Moving Beyond the Law of the Fathers Toni Morrison's Paradise

Law Text Culture Volume 5 Issue 1 Law & The Sacred Article 17 January 2000 Moving Beyond the Law of The Fathers Toni Morrison's Paradise M. M. Slaughter University of Kent Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Slaughter, M. M., Moving Beyond the Law of The Fathers Toni Morrison's Paradise, Law Text Culture, 5, 2000. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol5/iss1/17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Moving Beyond the Law of The Fathers Toni Morrison's Paradise Abstract You don't have to know the work of the legal theorist, Pierre Legendre, to read Toni Morrison's new novel, Paradise (Morrison 1997) but it doesn't hurt. The novel is not ostensibly about law (as one might expect, in Paradise there is no crime). Nevertheless, law is central to the novel. It is what the paradisal community rests on, the foundation of the symbolic order. It lays down what would be taken to be the inalterable places of this society and culture. Law is constitutive, what constitutes, constitutional; which as we shall see is no fortuitous analogy. Paradise is a story of foundations, or foundational myths, at the center of which is law. With unusual uncanniness, these not-so-buried themes in Morrison's work overlap with Legendre's psychoanalytically based legal theories. If his work is an explication and explanation of the symbolic function of law -- what rests in society's legal unconscious -- Morrison's novel is an illustration of it. -

The Poor Law of Lunacy

The Poor Law of Lunacy: The Administration of Pauper Lunatics in Mid-Nineteenth Century England with special Emphasis on Leicestershire and Rutland Peter Bartlett Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London. University of London 1993 Abstract Previous historical studies of the care of the insane in nineteenth century England have been based in the history of medicine. In this thesis, such care is placed in the context of the English poor law. The theory of the 1834 poor law was essentially silent on the treatment of the insane. That did not mean that developments in poor law had no effect only that the effects must be established by examination of administrative practices. To that end, this thesis focuses on the networks of administration of the poor law of lunacy, from 1834 to 1870. County asylums, a creation of the old (pre-1834) poor law, grew in numbers and scale only under the new poor law. While remaining under the authority of local Justices of the Peace, mid-century legislation provided an increasing role for local poor law staff in the admissions process. At the same time, workhouse care of the insane increased. Medical specialists in lunacy were generally excluded from local admissions decisions. The role of central commissioners was limited to inspecting and reporting; actual decision-making remained at the local level. The webs of influence between these administrators are traced, and the criteria they used to make decisions identified. The Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic asylum provides a local study of these relations. Particular attention is given to admission documents and casebooks for those admitted to the asylum between 1861 and 1865. -

Teaching Notes Mortal Fire by Elizabeth Knox Synopsis Sixteen-Year-Old Canny Mochrie Has Always Been a Little Different. She

Teaching Notes Mortal Fire by Elizabeth Knox Synopsis Sixteen-year-old Canny Mochrie has always been a little different. She has never known her father, she has always had a calculating, mathematical mind, and she has always been able to see something ‘Extra’. When she grudgingly joins her older stepbrother on a trip to research a strange coal mine disaster that happened thirty years earlier, she wanders into a nearby enchanted valley, occupied almost entirely by children all with the same surname and who can perform a type of magic that makes things stronger and better than they already are. With the help of the alluring and somewhat threatening Ghislain Zarene, who is held hostage by a powerful, out-of-control spell for his part in that mine accident long ago, Canny starts to untangle the mysteries of the valley, only to find that its secrets are also her own. 1 The Author Elizabeth Knox has published several novels for adults and children, as well as autobiographical novellas. Her acclaimed adult novel The Vintner’s Luck (1998) was shortlisted for the Orange Prize in 1999, and was made into a feature film in 2009. In 2008, her young adult novel Dreamquake won an American Library Association’s Michael L Printz Award for excellence in young adult literature. Elizabeth lives in Wellington, New Zealand. Her website and blog can be found at www.elizabethknox.com. Themes This mysterious and compelling coming-of-age novel has several themes, including the importance of history, the search for identity, otherness, secrets and memories, loyalty and love. -

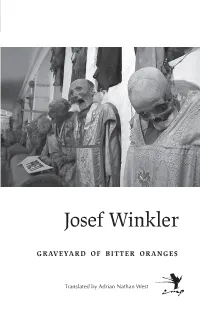

Graveyard of Bitter Oranges / Josef Winkler; Translated from First Contra Mundum Press the Original German by Adrian Edition 2015

“Graveyard of Bitter Oranges is a monstrous book, written with unequalled intensity.” Josef Winkler Josef .—Marcel Reich-Ranicki “Reading Winkler is like peering harder and harder into one of those painted Flemish hells that seethe with horribly inventive details of sin & retribution.” .—Alberto Manguel In 1979, Josef Winkler appeared on the literary horizon as if from nowhere, collecting numerous honors& the praise of the most promi- nent critical voices in Germany and Austria. Throughout the 1980s, he chronicled the malevolence, dissipation, and unregenerate Nazism en- Graveyard of Oranges Bitter demic to Austrian village life in an increasingly trenchant& hallucina- tory series of novels. At the decade’s end, fearing the silence that always lurks over the writer’s shoulder, he abandoned the Hell of Austria for Rome: not to flee, but to come closer to the darkness. There, he passes his days & nights among the junkies, rent boys, gypsies, & transsexuals who congregate around Stazione Termini and Piazza dei Cinquecento, as well as in the graveyards & churches, where his blasphemous reveries render the most hallowed rituals obscene. Traveling south to Naples& Palermo, he writes down his nightmares & recollections and all that he sees and reads, engaged, like Rimbaud, in a rational derangement of the senses, but one whose aim is a ruthless condemnation of church & state and the misery they sow in the lives of the downtrodden. Equal parts memoir, dream journal, and scandal sheet, the novel is, in the author’s words, a cage drawn around the horror. Writing here is an act of com- Josef Winkler memoration and redemption, a gathering of the bones of the forgotten dead and those outcast and spit on by society, their consecration in art, their final repatriation to the book’s titular graveyard. -

Adam Bede by George Eliot Book One Chapter I the Workshop with a Single Drop of Ink for a Mirror, the Egyptian Sorcerer Undertak

Adam Bede by George Eliot Book One Chapter I The Workshop With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader. With this drop of ink at the end of my pen, I will show you the roomy workshop of Mr. Jonathan Burge, carpenter and builder, in the village of Hayslope, as it appeared on the eighteenth of June, in the year of our Lord 1799. The afternoon sun was warm on the five workmen there, busy upon doors and window-frames and wainscoting. A scent of pine-wood from a tentlike pile of planks outside the open door mingled itself with the scent of the elder-bushes which were spreading their summer snow close to the open window opposite; the slanting sunbeams shone through the transparent shavings that flew before the steady plane, and lit up the fine grain of the oak panelling which stood propped against the wall. On a heap of those soft shavings a rough, grey shepherd dog had made himself a pleasant bed, and was lying with his nose between his fore-paws, occasionally wrinkling his brows to cast a glance at the tallest of the five workmen, who was carving a shield in the centre of a wooden mantelpiece. It was to this workman that the strong barytone belonged which was heard above the sound of plane and hammer singing-- Awake, my soul, and with the sun Thy daily stage of duty run; Shake off dull sloth.. -

Willa Cather's My Mortal Enemy: the Concise Presentation of Scene, Character, and Theme

Colby Quarterly Volume 10 Issue 3 September Article 4 September 1973 Willa Cather's My Mortal Enemy: The Concise Presentation of Scene, Character, and Theme Theodore S. Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 10, no.3, September 1973, p.138-148 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Adams: Willa Cather's My Mortal Enemy: The Concise Presentation of Scene 138 Colby Library Quarterly thing else" (111). It is so different, in fact, that it is irrelevant for Nellie, whose disillusionment leaves her hopeless. Is Nellie's hopeless conclusion also Miss Cather's? The novel offers no grounds for thinking otherwise. The compactness and starkness of My Mortal Enemy suggest that Miss Cather had full confidence in the accuracy of this conclusion and in her talents as a writer. Some may find it ironic that the book in which she gained the surest control of her art expresses her most despairing vision of life, but is it really? She was soon to make a journey to New Mexico and to discoveries that would brighten her spirits and give a new serenity to her later novels. Is it not, rather, entirely consistent with her devotion to her art that, when life seemed to fail her, her art saved her? WILLA CATHER'S MY MORTAL ENEMY: THE C'ONCISE PRESENTATION OF SCENE, CHARACTER, AND THEME By THEODORE S. -

The Books of Mortals Ted Dekker

The Books of Mortals SOVEREIGN TED DEKKER AND TOSCA LEE New York Boston Nashville Sovereign_HCtextF1.indd iii 3/12/13 10:33:59 PM This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental. Copyright © 2013 by Ted Dekker All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. FaithWords Hachette Book Group 237 Park Avenue New York, NY 10017 faithwords.com Printed in the United States of America RRD-C First Edition: June 2013 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FaithWords is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The FaithWords name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dekker, Ted, 1962– Sovereign : the Books of Mortals / Ted Dekker and Tosca Lee.—First Edition.