The Audiovisual Elements and Styles in Computer and Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the Periphery of Mainstream Culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino

ISSN 2280-7705 www.gamejournal.it Published by LUDICA Issue 03, 2014 – volume 1: JOURNAL (PEER-REVIEWED) VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the periphery of mainstream culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino GAME JOURNAL – Peer Reviewed Section Issue 03 – 2014 GAME Journal A PROJECT BY SUPERVISING EDITORS Antioco Floris (Università di Cagliari), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Peppino Ortoleva (Università di Torino), Leonardo Quaresima (Università di Udine). EDITORS WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Marco Benoît Carbone (University College London), Giovanni Caruso (Università di Udine), Riccardo Fassone (Università di Torino), Gabriele Ferri (Indiana University), Adam Gallimore (University of Warwick), Ivan Girina (University of Warwick), Federico Giordano (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Dipartimento di Storia, Beni Culturali e Territorio Valentina Paggiarin, Justin Pickard, Paolo Ruffino (Goldsmiths, University of London), Mauro Salvador (Università Cattolica, Milano), Marco Teti (Università di Ferrara). PARTNERS ADVISORY BOARD Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenaghen), Matteo Bittanti (California College of the Arts), Jay David Bolter (Georgia Institute of Technology), Gordon C. Calleja (IT University of Copenaghen), Gianni Canova (IULM, Milano), Antonio Catolfi (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Mia Consalvo (Ohio University), Patrick Coppock (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Ruggero Eugeni (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Enrico Menduni (Università di -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics Simon Niedenthal Malmö University, School of Arts and Communication Malmö, Sweden [email protected] Abstract: Fireworks in games translate the sensory power of a real-world aesthetic form to the realm of digital simulation and gameplay. Understanding the role of fireworks in games can best be pursued through through a threefold aesthetic perspective that focuses on the senses, on art, and on the aesthetic experience that gives pleasure through the player’s participation in the simulation, gameplay and narrative potentials of fireworks. In games ranging from Wii Sports and Fantavision, to Okami and Assassin’s Creed II, digital fireworks are employed as a light effect, and are also the site for gameplay pleasures that include design and performance, timing and rhythm, and power and awe. Fireworks also gain narrative significance in game forms through association with specific sequences and characters. Ultimately, understanding the role of fireworks in games provokes us to reverse the scrutiny, and to consider games as fireworks, through which we experience ludic festivity and voluptuous panic. Keywords: Fireworks, Pyrotechnics, Digital Games, Game Aesthetics 1. Introduction: On March 9th, 2000, Sony released the fireworks-themed Fantavision (Sony Computer Entertainment 2000) in Japan as one of the very first titles for its then new Playstation 2. Fantavision exhibits many of the desirable qualities for good launch title: simulation properties that show off new graphic capabilities, established gameplay that is quick to grasp, a broad appeal. Though the critical reception for the game was ultimately lukewarm (a 72 rating from Metacritic.com), it is notable that Sony launched its new console with a fireworks game. -

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

Présentation Powerpoint

Compatible Games 1941 Frozen Front Chicken Invaders Dr. Droid 3D MOTOR Chicken Invaders 2 DRAG racing 4 seasons Hunt 3D Chicken Invaders 3 Dream League Soccer Acceler 8 Chicken Invaders 4 Dungeon Hunter 3 Aces of the Luftwaffe Chrono&Cash Dungeon Hunter4 Aftermath XHD Clash - Space Shooter Dungeon Quest Angry Birds GO Cordy EDGE Extended Another World Cordy 2 EtERNITY WARRIORS Antigen Crazy Snowboard ETERNITY WARRIORS 2 Arma Tactics Critter Rollers EVAC HD Army Academy CS portable Everland: Unleashed Asphalt 5 Cup! Cup! Golf 3D! ExZeus Asphalt 6 Dark Incursion ExZeus 2 Asphalt 7 DB42 Farm Invasion USA Asphalt 8 Airborne Dead Effect Farming Simulator Asteriod 2012 Dead Rushing HD Fields Of Battle Auralux Dead Space Final Freeway 2R Avenger Dead Trigger FIST OF AWESOME AVP: Evolution Dead Trigger 2 Forsaken Planet B.M.Snowboard Free DEER HUNTER 2012 Fractal Combat Babylonian Twins Platform Game DEER HUNTER 2013 Fright fight Bermuda Dash DEER HUNTER 2014 Gangstar Vegas Beyond Ynth Dig! Grand Theft Auto : Vice City Beyond Ynth Xams edition Digger HD Grand Theft Auto III Bike Mania Dink smallwood Gravi Bird Bomb Diversion Grudger Blasto! Invaders Dizzy - Prince of the Yolkfolk GT Racing 2 Blazing Souls Acceleration Doom GLES Guns n Glory Block Story Doptrix Gunslugs Brotherhood of Violence II Double Dragon Trilogy Halloween Temple'n Zombies Run Compatible Games Helium Boy Demo Overdroy Sonic 4 Episode II Heretik GLEX Particle arcade shooter Sonic CD Heroes of Loot PewPew Sonic Racing transformed Hexen GLES Pinball Arcade Sonic the Hedgehog -

Considerations for a Study of a Musical Instrumentality in the Gameplay of Video Games

Playing in 7D: Considerations for a study of a musical instrumentality in the gameplay of video games Pedro Cardoso, Miguel Carvalhais ID+, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract. The intersection between music and video games has been of increased interest in academic and in commercial grounds, with many video games classified as ‘musical’ having been released over the past years. The purpose of this paper is to explore some fundamental concerns regarding the instrumentality of video games, in the sense that the game player plays the game as a musical or sonic instrument, an act in which the game player becomes a musical performer. We define the relationship between the player and the game system (the musical instrument) to be action- based. We then propose that the seven discerned dimensions we found to govern that relationship to also be a source of instrumentality in video games. Something that not only will raise a deeper understanding of musical video games but also on how the actions of the player are actually embed in the generation and performance of music, which, in some cases, can be transposed to other interactive artefacts. In this paper we aim at setting up the grounds for discussing and further develop our studies of action in video games intersecting it with that of musical performance, an effort that asks for multidisciplinary research in musicology, sound studies and game design. Keywords: Action, Gameplay, Music, Sound, Video games. Introduction Music and games are no exception when it comes to the ubiquity of computational systems in contemporary society. -

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen Citation Bogost, Ian. Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006. Keywords: Mythical and scientific modes of thought (bricoleur vs. engineer), bricolage, cyber texts, ergodic literature, Unit operations. Games: Zork I. Argument & Perspective Ian Bogost’s “unit operations” that he mentions in the title is a method of analyzing and explaining not only video games, but work of any medium where works should be seen “as a configurative system, an arrangement of discrete, interlocking units of expressive meaning.” (Bogost x) Similarly, in this chapter, he more specifically argues that as opposed to seeing video games as hard pieces of technology to be poked and prodded within criticism, they should be seen in a more abstract manner. He states that “instead of focusing on how games work, I suggest that we turn to what they do— how they inform, change, or otherwise participate in human activity…” (Bogost 53) This comparative video game criticism is not about invalidating more concrete observances of video games, such as how they work, but weaving them into a more intuitive discussion that explores the true nature of video games. II. Ideas Unit Operations: Like I mentioned in the first section, this is a different way of approaching mediums such as poetry, literature, or videogames where works are a system of many parts rather than an overarching, singular, structured piece. Engineer vs. Bricoleur metaphor: Bogost uses this metaphor to compare the fundamentalist view of video game critique to his proposed view, saying that the “bricoleur is a skillful handy-man, a jack-of-all-trades who uses convenient implements and ad hoc strategies to achieve his ends.” Whereas the engineer is a “scientific thinker who strives to construct holistic, totalizing systems from the top down…” (Bogost 49) One being more abstract and the other set and defined. -

Homosexuality As Seen in Grand Theft Auto Iv

HOMOSEXUALITY AS SEEN IN GRAND THEFT AUTO IV A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining The Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: YUNIARTI 10150025 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2014 ABSTRACT Homosexuality as seen in Grand Theft Auto IV By Yuniarti Grand Theft Auto IV is a form of RPG game created by Rockstar Games in 2008. GTA IV has two additional episodes, namely GTA IV: The Lost and Damned and GTA IV : The Ballad of Gay Tony. The analysis is focused on GTA IV: The Ballad of Gay Tony. This game tells about the life of Tony Prince who has debts taken from his business friends. Since then, Gay Tony asks Luis to do extra work provided by his business friends to redeem the debt. Problems come and go when he tried to redeem his debts and eventually Luis is able to resolve the issue at the end. To analyze Gay Tony, qualitative research method is used to find out how homosexuality is presented by Tony Prince and to reveal how Tony sees himself in being homosexual. The analysis begins with Gay Tony’s homosexual background. Further analysis is divided into several parts, that is conversation of text and visual effects that appear in the game. Conversation was divided into two parts, namely the influence to the other characters and conversations that related to homosexuality. In the visual, the author divides into two, namely the appearance of characters and loading screen image. The writer concludes that the character is an openly homosexual. -

Myst 3 Exile Mac Download

Myst 3 exile mac download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Myst III: Exile Patch for Mac Free UbiSoft Entertainment Mac/OS Classic Version Full Specs The product has been discontinued by the publisher, and renuzap.podarokideal.ru offers this page for Subcategory: Sudoku, Crossword & Puzzle Games. The latest version of Myst III is on Mac Informer. It is a perfect match for the General category. The app is developed by Myst III renuzap.podarokideal.ruin. Myst III: Exile X for Mac Free Download. MB Mac OS X About Myst III: Exile X for Mac. The all NEW sequel to Myst and Riven new technology, new story and a new arch enemy. It's the perfect place to plan revenge. The success of Myst continues with 5 entirely new ages to explore and a dramatic new storyline, which features a pivotal new character. This version is the first release on CNET /5. Myst III (3): Exile (Mac abandonware from ) Myst III (3): Exile. Author: Presto Studios. Publisher: UbiSoft. Type: Games. Category: Adventure. Shared by: MR. On: Updated by: that-ben. On: Rating: out of 10 (0 vote) Rate it: WatchList. ; 3; 0 (There's no video for Myst III (3): Exile yet. Please contribute to MR and add a video now!) What is . myst exile free download - Myst III: Exile X, Myst III: Exile Patch, Myst IV Revelation Patch, and many more programs. 01/07/ · Myst III Exile DVD Edition - Windows-Mac (Eng) Item Preview Myst III Exile DVD Edition - renuzap.podarokideal.ru DOWNLOAD OPTIONS download 1 file. ITEM TILE download. download 1 file. -

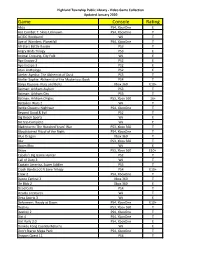

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Excavating the Page: Virtuosity and Illusionism in Italian Book Illumination, 1460–1520 Nicholas Herman Available Online: 02 Aug 2011

This article was downloaded by: [Metropolitan Museum of Art] On: 08 August 2011, At: 08:06 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Word & Image Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/twim20 Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, 1460–1520 Nicholas Herman Available online: 02 Aug 2011 To cite this article: Nicholas Herman (2011): Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, 1460–1520, Word & Image, 27:2, 190-211 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2010.526289 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, – NICHOLAS HERMAN So we must advance from the concrete whole to the several These pictorial layers, their distance relative to the viewer, constituents which it embraces; for it is the concrete whole and their progression from literal presence (the clusters of jew- that is the more readily recognizable by the senses. -

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction T.C. Nicholas Graham [email protected] http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/wiki/index.php/CISC_877 Winter term, 2010 equis: engineering interactive systems Topics include… Timeline and Marking Scheme Video game design Gaminggp platforms and fundamental technolo gies Activity Due Date Grade January 26, Game development processes and pipeline Project Proposal (2-3 pages, hand-in) 10% 2010 Software architecture of video games Progress Presentation (involves Mar 2, 2010 20% Video games as distributed systems presentation and online report) Game physics Informal progress reports Weekly 5% GAIGame AI April 6, 2010 Scripting languages Final Project Presentation / Show 10% (tentative) Game development tools Final Project Report April 9, 2010 45% Social and ethical aspects of video games Class Participation 10% User in terf aces of gam es equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems Homework Project proposal (for next week) Wiki contains detailed description of project ideas, game you will be extending The Project Proposal to be posted on Wiki – create yourself an account Form your own project groups – pick project appropriate to group size OGRE tutorials (over next two weeks) …see Wiki for details Download URL: http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/~graham/cisc877/soft/ equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems The Game: Life is a Village The Game: Life is a Village Goal is to build an interesting village