Federal Programs for Addressing Low-Income Housing Needs a Policy Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ending Homelessness for Families: the Evidence for Affordable Housing

Ending Homelessness for Families The Evidence for Affordable Housing Marybeth Shinn Community development corporations (CDCs) help revitalize communities and meet the affordable housing needs of low-income families. By offering residents such services as employ- ment support, financial literacy training and after-school activities, many organizations also effectively propel families to greater social well-being and economic self-sufficiency. CDCs can further strengthen families and communities by working to end family homeless- ness. Communities are increasingly adopting new strategies to prevent homelessness and to rapidly secure permanent housing for families when they do become homeless. These commu- nity-based organizations are shifting practices and achieving results. But substantive progress requires broader networks and commitments, including the expertise and resources of the affordable housing and community development industry. Enterprise Community Partners and the National Alliance to End Homelessness are committed to working together to forge local part- nerships that end family homelessness. he continuing crisis in affordable housing has led returns to stable housing and shows that housing Tto a situation in which all too many poor fami- that families can afford is sufficient to end home- lies have become homeless. Many of these parents lessness – or to prevent it – for most families. came of age when housing costs were high, and they Extensive research demonstrates that housing sub- were never able to break into the housing market. sidies solve homelessness for the majority of fami- Others have lost housing and cannot find a new lies. In some jurisdictions, programs have home that they can afford. For the vast majority of succeeded in re-housing families even without families, affordable housing, typically secured with a ongoing subsidies. -

PVD Affordable Housing Appraisal Guide 2019

KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE DIVISION OF PROPERTY VALUATION AFFORDABLE HOUSING APPRAISAL GUIDE for the STATE OF KANSAS 2021 EFFECTIVE DATE OF APPRAISAL GUIDE JANUARY 1, 2021 Division of Property Valuation, 300 SW 29th St., PO Box 3506, Topeka, KS 66601-3506 Phone (785)296-2365 Fax (785)296-2320 http://www.ksrevenue.org/pvd Affordable Housing Appraisal Guide - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 2 PURPOSE ........................................................................................................................... 4 APPRAISAL REQUIREMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 WHAT IS AFFORDABLE HOUSING? ..................................................................................... 8 AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................. 9 AFFORDABLE HOUSING RESOURCES ................................................................................. 13 AFFORDABLE HOUSING APPRAISAL INFORMATION .......................................................... 14 CAPITALIZATION RATE ANALYSIS ...................................................................................... 17 INCOME VALUATION TEMPLATE ....................................................................................... 25 NON-STABILIZED PROPERTIES .......................................................................................... -

DC's Vanishing Affordable Housing

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org March 12, 2015 Going, Going, Gone: DC’s Vanishing Affordable Housing By Wes Rivers Introduction Rapidly rising housing costs led to a substantial loss of low-cost rental housing in the District over the last decade, yet there was little growth in wages for many residents, which means that rent is increasingly eating away at household budgets. As the District’s high cost of living continues to outpace incomes, more and more residents struggle to pay for housing while also meeting other necessities like food, clothing, health care, and transportation. The loss of affordable housing threatens the physical and mental health of families, makes it harder for adults to find and keep a job, creates instability for children that makes it hard to focus at school, and leaves thousands at risk of homelessness at any given moment. This analysis looks at the costs of rent and utilities paid by District residents over the last decade, and how these trends have affected residents’ ability to afford and live in DC, using data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The findings suggest that policymakers need a comprehensive strategy to preserve the low-cost housing that now exists and to create more affordable housing options in the city. Rents have grown sharply but incomes have not for many DC households. For example, rents for residents with incomes of about $22,000 a year increased $250 a month over the past decade, adjusting for inflation, while incomes remained flat. -

2019 Assisted Housing List

Assisted Housing In The City of Alexandria Alexandria Office of Housing 421 King Street, Suite 215 Alexandria, VA 22314 703-746-4990 ASSISTED HOUSING PROGRAMS IN THE CITY OF ALEXANDRIA Within Alexandria, both public and private owners of rental housing offer assisted housing affordable to low and moderate income residents of the City through participation in state, local or federal programs. These units are available to income eligible households and some programs give priority or restrict admission to specific populations such as elderly or disabled residents. Public Housing and the Housing Choice Voucher Program The Alexandria Redevelopment and Housing Authority (ARHA) owns and manages public housing in the City of Alexandria. ARHA also administers the federal Housing Choice Voucher program (formerly known as the Section 8 program.) Both programs have waiting lists maintained by ARHA. ARHA owns almost 1200 housing units in the City of Alexandria, most of which were built or acquired using federal public housing funds. These units include townhouses, apartments and condominium units, and are located throughout the City. Public housing residents pay 30% of the household’s adjusted income for rent ARHA also administers the Federal Housing Choice Voucher rental subsidy program (formerly knows as the Section 8 Program) for the City of Alexandria. Participants in the Housing Choice Voucher Program receive assistance to rent privately-owned housing units that are located in apartment complexes, condominiums, townhouses, or single-family homes. For more information contact ARHA directly at (703) 549-7115. Additional information can be found on ARHA’s website at www.arha.us. Privately Owned Subsidized Housing Some multifamily apartment complexes participate in federal programs that are subsidized through programs that allow eligible households to pay 30% of their income for rent. -

The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households

Discussion Paper The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households Spencer Agnew Graduate Student University of Minnesota, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs Research and Evaluation Unit Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Does Affordable Housing Impact Surrounding Property Values? .................... 5 Chapter 2: Does Affordable Housing Impact Neighborhood Crime? .............................. 10 Chapter 3: Does Affordable Housing Impact Health Outcomes? ..................................... 14 Chapter 4: Does Affordable Housing Impact Education Outcomes? ............................... 19 Chapter 5: Does Affordable Housing Impact Wealth Accumulation, Work, and Public Service Dependence? ........................................................................................................ 24 2 Executive Summary Minnesota Housing finances and advances affordable housing opportunities for low and moderate income Minnesotans to enhance quality of life and foster strong communities. Overview Affordable housing organizations are concerned primarily with helping as many low and moderate income households as possible achieve decent, affordable housing. But housing units do not exist in a vacuum; they affect the neighborhoods they are located in, as well as the lives of their residents. The mission statement of Minnesota Housing (stated above) reiterates the connections between housing, community, and quality -

Connecting Residents of Subsidized Housing with Mainstream Supportive Services: Challenges and Recommendations

Connecting Residents of Subsidized Housing with Mainstream Supportive Services: Challenges and Recommendations Rebecca Cohen December 2010 Connecting Residents of Subsidized Housing with Mainstream Supportive Services: Challenges and Recommendations Rebecca Cohen Center for Housing Policy December 2010 The research contained herein is part of the What Works Collaborative, which provides rapid response analysis and research to HUD to help inform the implementation of a forward‐looking housing and urban policy agenda. The Research Collaborative is supported by The Rockefeller Foundation, Surdna Foundation Inc., The Ford Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The findings in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the What Works Collaborative or The Rockefeller Foundation, Surdna Foundation, Inc., The Ford Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, or the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Bill Kelly and Paul Weech of Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future in conceptualizing and providing feedback on earlier drafts of this report, as well as the assistance of Judy Chavis, Mary Cunningham, Ted Houghton, Stuart Kaplan, Jan Monks, Ruth Schwartz, Lexi Turner, and Evelyn Wolff. Special thanks to Maureen Friar, Rick Haughey, and Jeffrey Lubell. Individuals from the following organizations were also consulted in preparation of this report: Alternative -

Federally Subsidized Housing – Unit Based

Federally Subsidized Housing – Unit Based What is federally subsidized housing? Federally subsidized housing means that the government pays part or all of your rent. The part of your rent the government pays is called the "subsidy." Unlike private rental housing, landlords in federally subsidized housing have many more rules to follow. These rules talk about who gets into the housing (admissions), rents, leases, grievances, and evictions. If you live in federally subsidized housing, you have more legal rights than tenants in private rental housing. These rights include the following things: The landlord must follow certain rules about who gets admitted to the housing. Your rent is limited. Usually you pay no more than 30% of your income for rent and utilities. Your tenancy usually is not time limited. As long as you don't break the lease or the law, you are allowed to stay. You may be evicted only for good cause. Usually you must be given notice and a chance to contest a denial of admission. Before your subsidy may be ended, you must be given notice and a chance to contest. What are the types of federally subsidized housing? There are two types of federally subsidized housing. In one type, the subsidy is tied to the housing unit. This is called "unit-based assistance." In the other type, the subsidy is tied to the THIS INFORMATION IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE Leslie Dodson,, Esq., 217 East Third Street, Farmville, VA 23901, is responsible for the contents of this publication. 1 7/21/2017 tenant. This is called "tenant-based assistance." This article is about unit-based assisted housing. -

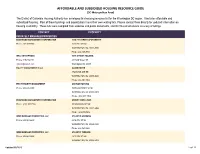

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

Legal Basics of Subsidized Housing Rents

Legal Basics of Subsidized Housing Rents Lisa Sitkin, National Housing Law Project March 10, 2020 Housekeeping • All on mute. Use Questions function for substantive questions and for technical concerns. • Problems getting on the webinar? Send an e- mail to [email protected]. • Written materials and a recording will be available at NCLER.acl.gov. See also the chat box for this web address. 2 About NCLER The National Center on Law and Elder Rights (NCLER) provides the legal services and aging and disability communities with the tools and resources they need to serve older adults with the greatest economic and social needs. A centralized, one- stop shop for legal assistance, NCLER provides Legal Training, Case Consultations, and Technical Assistance on Legal Systems Development. Justice in Aging administers the NCLER through a contract with the Administration for Community Living’s Administration on Aging. 3 About NHLP The National Housing Law Project (NHLP) is a non- profit legal advocacy and resource center focused on increasing, preserving, and improving affordable housing; expanding and enforcing the rights of low- income tenants and homeowners; and increasing housing opportunities for underserved communities. NHLP provides technical assistance and policy and litigation support on a range of housing issues to legal services and other advocates in California and nationwide. 4 Overview 1. Subsidized housing programs we will cover 2. What does the “rent” include? 3. Rent-setting methods 4. Calculating income for income-based rents 5. Issues -

Preservation Strategies for Mobile Home Parks: Lessons from Miami-Dade County by Chuck Elsesser

Lil' Abner mobile home park in Miami Dade provides housing for approximately 900 extremely low income families, living under the threat of losing their homes. Preservation Strategies for Mobile Home Parks: Lessons from Miami-Dade County By Chuck Elsesser he Shimberg Center at the University of charged in a highly subsidized two bedroom Low Florida calculated that in 2000 there were Income Housing Tax Credit apartment targeted to HTover 42,000 mobile homes in parks in the same income level. Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. While the hyperinflation of real estate prices in South The Miami-Dade planning study goes on to paint Florida during the past five years took its toll on a grim picture for the future of these mobile all forms of affordable housing, perhaps no type home parks. of housing has been as threatened as these mobile homes. The challenge we are facing is the elimination of these housing units that are the only shelter many of the A recent study by the Planning Department in Miami-Dade County residents can afford...Existing supply of affordable County found that since 2000 the number of mobile home and workforce units are not adequate to meet the needs of residents in Miami-Dade County has decreased by more the county residents...Depleting this limited short supply of than 3,000 people. The number of occupied mobile homes housing affordable to them would only exacerbate our had decreased by over 7 percent. Virtually all of these existing affordable housing crisis. “lost” mobile homes represented unsubsidized affordable housing for some of the County’s most vulnerable residents. -

Subsidized Housing and Employment Building Evidence About What Works to Improve Self-Sufficiency

An MDRC Working Paper Subsidized Housing and Employment Building Evidence About What Works to Improve Self-Sufficiency James A. Riccio Prepared for Revisiting Rental Housing: A National Policy Summit A Symposium Organized by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies and Supported by the MacArthur Foundation November 14 and 15, 2006 March 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Sandra Newman and Joseph Harkness of the Institute for Policy Stud- ies at Johns Hopkins University for helping me construct the overall framework for this pa- per and for contributing substantially to the presentation in certain sections. I would also like to thank Eric Belsky of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University for very helpful comments on an earlier draft. ii Abstract For many years, policymakers have agreed that low-income, working-age people who receive government rent subsidies ought to strive for self-sufficiency and that the housing sub- sidy system should play an actively supportive role — or at least not stand in the way. This in- tent is clear in the most recent major public housing reform legislation, the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA) of 1998, which makes promoting residents’ self- sufficiency a core objective. A variety of self-sufficiency innovations and housing policy re- forms have been tried over the past two decades, and new ones are being proposed all the time. Yet what is striking about innovation in this field is that so little of it is based on credible evi- dence of “what works.” This paper, which was prepared for “Revisiting Rental Housing: A National Policy Summit,” a November 2006 symposium organized by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies and supported by the MacArthur Foundation, argues for building a stronger base of evi- dence in the housing-employment policy arena through an expanded use of randomized con- trolled trials. -

Philadelphia's Changing Neighborhoods

A report from May 2016 Philadelphia’s Changing Neighborhoods Gentrification and other shifts since 2000 Contents 1 Overview 3 Gentrification in Philadelphia Defining gentrification 3 Gentrified neighborhoods 5 9 Types of neighborhoods that gentrified in Philadelphia Predominantly working-class African-American neighborhoods 9 Old industrial areas 17 Mixed-income, mostly white neighborhoods 22 Center City and adjacent areas 28 33 Other types of neighborhood change University areas that are no longer majority African-American 33 Neighborhoods with other demographic shifts and real estate market change 37 Public housing redevelopment areas 38 Areas that are losing ground economically 38 40 Shaping neighborhood change through public policy Programs already in place 41 Property tax abatement 41 Property tax reform and relief programs 41 Housing counseling 42 Basic systems repair 42 Subsidized units in gentrified neighborhoods 42 Empowering residents, old and new 42 Strategies in development or under discussion 43 44 Conclusion 45 Endnotes About this report This report was researched and written by Emily Dowdall, an ocer with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Philadelphia research initiative. Additional research and analysis was provided by the Policy Solutions team at Reinvestment Fund, a national community development financial institution based in Philadelphia. Assistance by Pew colleagues included an extensive methodology review by Alan van der Hilst and analytic support by Michelle Schmitt. The report was edited by Larry Eichel, director of the Philadelphia research initiative, along with Elizabeth Lowe, Daniel LeDuc, and Bernard Ohanian. Kodi Seaton was the designer, and Bradley Maule and Katye Martens provided photographs. Acknowledgments In producing this report, the author interviewed numerous public ocials, community development experts, and city residents who provided important insights into neighborhood change in Philadelphia.