David Ross Mccord and the Makings of Canadian History Kathryn Harvey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb A Thesis In the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2015 © Heather McNabb 2015 ii iii ABSTRACT Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb, PhD. Concordia University, 2015 This dissertation is an exploration of the changing role of photographs used in the dissemination of history by a twentieth-century Canadian history museum. Based on archival research, the study focuses on some of the changes that occurred in museum practice over four and a half decades at Montreal’s McCord Museum. The McCord was in many ways typical of other small history museums of its time, and this work illuminates some of the transformations undergone by other similar organizations in an era of professionalization of many fields, including those of academic and public history. Much has been written in recent scholarly literature on the subject of photographs and the past. Many of these works, however, have tended to examine the original context in which the photographic material was taken, as well as its initial use(s). Instead, this study takes as its starting point the way in which historic photographs were employed over time, after they had arrived within the space of the museum. Archival research for this dissertation suggests that photographs, initially considered useful primarily for reference purposes at the McCord Museum in the early twentieth century, gradually gained acceptance as historical objects to be exhibited in their own right, depicting specific moments from the past to visitors. -

Behind the Roddick Gates

BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES REDPATH MUSEUM RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME III BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES VOLUME III 2013-2014 RMC 2013 Executive President: Jacqueline Riddle Vice President: Pamela Juarez VP Finance: Sarah Popov VP Communications: Linnea Osterberg VP Internal: Catherine Davis Journal Editor: Kaela Bleho Editor in Chief: Kaela Bleho Cover Art: Marc Holmes Contributors: Alexander Grant, Michael Zhang, Rachael Ripley, Kathryn Yuen, Emily Baker, Alexandria Petit-Thorne, Katrina Hannah, Meghan McNeil, Kathryn Kotar, Meghan Walley, Oliver Maurovich Photo Credits: Jewel Seo, Kaela Bleho Design & Layout: Kaela Bleho © Students’ Society of McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2013-2014 http://redpathmuseumclub.wordpress.com ISBN: 978-0-7717-0716-2 i Table of Contents 3 Letter from the Editor 4 Meet the Authors 7 ‘Welcome to the Cabinet of Curiosities’ - Alexander Grant 18 ‘Eozoön canadense and Practical Science in the 19th Century’- Rachael Ripley 25 ‘The Life of John Redpath: A Neglected Legacy and its Rediscovery through Print Materials’- Michael Zhang 36 ‘The School Band: Insight into Canadian Residential Schools at the McCord Museum’- Emily Baker 42 ‘The Museum of Memories: Historic Museum Architecture and the Phenomenology of Personal Memory in a Contemporary Society’- Kathryn Yuen 54 ‘If These Walls Could Talk: The Assorted History of 4465 and 4467 Blvd. St Laurent’- Kathryn Kotar & Meghan Walley 61 ‘History of the Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal’- Alexandria Petit-Thorne & Katrina Hannah 67 ‘The Hurtubise House’- Meghan McNeil & Oliver Maurovich ii Jewel Seo Letter from the Editor Since its conception in 2011, the Redpath Museum’s annual Research Journal ‘Behind the Roddick Gates’ has been a means for students from McGill to showcase their academic research, artistic endeavors, and personal pursuits. -

Proquest Dissertations

Women's Botanical Illustration in Canada: Its Gendered, Colonial and Garden Histories (1830-1930) Kimberlie M. Robert A Thesis in the Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2008 © Kimberlie M. Robert, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45323-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45323-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Stories of Canada: National Identity in Late-Nineteenth-Century English-Canadian Fiction" (2003)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 2003 Stories of Canada: National Identity in Late- Nineteenth-Century English-Canadian Fiction Elizabeth Hedler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hedler, Elizabeth, "Stories of Canada: National Identity in Late-Nineteenth-Century English-Canadian Fiction" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 193. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/193 This Open-Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. STORIES OF CANADA: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN LATE-NINETEENTH- CENTURY ENGLISH-CANADIAN FICTION Elizabeth Hedler B.A. McGill University, 1994 M.A. University of Maine, 1996 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2003 Advisory Commit tee: Marli F. Weiner, Professor of History, Co-Advisor Scott See, Professor of History and Libra Professor of History, Co-Advisor Graham Cam, Associate Professor of History, Concordia University Richard Judd, Professor of History Naorni Jacobs, Professor of English STORIES OF CANADA: NATIONAL IDENTITY IN LATE-NINETEENTH- CENTURY ENGLISH-CANADIAN FICTION By Elizabeth Hedler Thesis Co-Advisors: Dr. Scott W. See and Dr. Marli F. Weiner An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) May, 2003 The search for a national identity has been a central concern of English-Canadian culture since the creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867. -

Here! Login Home

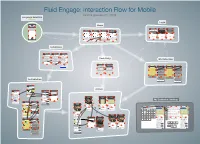

Fluid Engage: Interaction Flow for Mobile Draft 9 (January 21, 2010) Language Selection start here! Login Home Carrier 12:34 PM Language selection Default Successful login Invalid email address English Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Login Login Login Français Some note about how in this version, we only need your Some note about how in this version, we only need your Some noteYou've about entered how in an this invalid version, email we address.only need your In-museum default Out-of-museum default Language change Successful logout email address to identify you. No password needed, no email address to identify you. No password needed, no email address to identifyPlease you. try No again. password needed, no registration. To be written. registration. To be written. registration. To be written. Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Welcome, Email address [email protected] address ! Email address McCord Museum Login McCord Museum Login McCord Museum Login McCord Museum Login We'll take you back to the home screen now. You have been logged out. Cancel Login Cancel Login Cancel Login Exhibitions Collections Visitor Exhibitions Collections Visitor Exhibitions Collections Visitor Exhibitions Collections Visitor information information information information on-screen keyboard on-screen keyboard on-screen keyboard My collection Enter object Change My collection Enter object Change My collection Enter object Change My collection Enter object Change (0) code language (0) code language (0) code language (0) code language icon icon icon icon icon icon icon icon icon icon icon 64x64 64x64 64x64 64x64 64x64 64x64 64x64 Change64x64 language 64x64 64x64 64x64 Tours Museum Scan 2D Tours Museum Scan 2D Museum Scan 2D Tours Museum Scan 2D map barcode map barcode map Englishbarcode map barcode Change language Change language Français Change language Exhibitions Default (collapsed) Fully expanded Upcoming exhibition detail Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Carrier 12:34 PM Exhibitions Exhibitions Jewish Paint.. -

Location, Location, Location: David Ross Mccord and the Makings of Canadian History"

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article "Location, Location, Location: David Ross McCord and the Makings of Canadian History" Kathryn Harvey Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 19, n° 1, 2008, p. 57-82. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037426ar DOI: 10.7202/037426ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 03:12 Location, Location, Location: David Ross McCord and the Makings of Canadian History KATHRYN HARVEY Abstract This study of the McCord National Museum in Montreal examines the role of place in the creation of personal and public memory. The founder, David Ross McCord, sought to promote a version of Canadian history in which family and personal myth were conflated with that of nation. -

AICW Newsletter 77

VICE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dear Members Our Association has been very busy during this long winter and is looking forward to a Spring and Summer full of events that celebrate our members and their achievements. June, Italian Heritage Month, is fast approaching and our Books and Biscotti events are being planned all across Canada. As soon as they are finalized, information will be shared on our website, on Facebook and on Twitter. I thank those of you who are organizing these events and I encourage the others to think about organizing one as well. It is a way to come together, share our writings, our work, passion and experiences and celebrate our cultural and literary heritage. Association of Our conference committee is working diligently on every aspect of our upcoming Italian Canadian gathering in Padula, Italian-Canadian Literature: Departures, Journeys, Destinations, August 11-14, 2016. The committee includes Domenic Beneventi, Licia Canton, Venera Writers Fazio, Joseph Pivato, Maria Cristina Seccia and myself. We are currently working on the program. We will send out information about accommodations and travel tips very soon. Our 30th anniversary anthology is moving along slowly. The editorial committee – Delia De Santis, Venera Fazio, Caroline Morgan Di Giovanni and myself – is presently reading the numerous submissions. A big thanks to those who made submissions and Executive our appreciation for your patience. It is going to be a memorable anthology! President Domenic Beneventi Thank you to those who renewed their memberships. If you haven’t done so, please take five minutes today and visit our membership page: http://www.aicw.ca/become Vice-President Giulia De Gasperi -a-member. -

Indigenous Mcgill October 2019

Indigenous McGill Front: Thomas Daniel Green in Graduation Robes. “ J. D. Green, Mon- treal, QC, 1882,” Notman & Sandham May 6, 1882, II-65038.1 McCord Museum © McCord Museum The names of Indigenous McGill students, staff, and faculty are bolded in the text. Although I alone am responsible for the errors, shortcom- ings and ultimate choices made. The text benefitted immensely from the generous criticism of colleagues and I wish to acknowledge in particular Shannon Fitzpatrick, Laura Madokoro, and David Meren and the institu- tional knowledge of Martha Crago, Fred Genesee, Hudson Meadwell, and Toby Morantz. I am indebted to Molly Titus as the model intelligent read- er, to Marieke de Roos for design assistance and the Student Society of McGill, the McGill Daily, the Manitoba Archives, McCord Museum, McGill and McGill University for their permission to reproduce images. Finally, I wish to recognize the history undergraduates who sparked this project with their undergraduate course research. I look forward to learning from them in their future work. Suzanne Morton 2019 Indigenous McGill The principle that it is impossible to move forward on Indigenous issues without being informed by the past, is central to current discussion on campus and in the wider community. In this vein, the Provost’s Task Force on Indigenous Studies and Indigenous Education (2017) has challenged us to conduct a critical self-study of “the historical relationship of McGill University with Indigenous communities and peoples.” This booklet is meant to represent a preliminary contribution, a placeholder while the larger university project awaits action. It starts with the premise: McGill’s history is Indigenous history, and the university’s campus has always been Indigenous space. -

2011-2012 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2011/2012 McCORD MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 20112012 ROACH 1875-1925. GIFT OF MISS MABEL MOLSON. M6706 © McCorD MUseUM. 02 Message from the Chair 24 The Museum’s of the Board of Trustees Educational Mission 03 Message from the President 26 Cultural Activities and Chief Executive Officer 29 Breadth 06 2011/12 In Review 31 The McCord Museum 08 Collections/Acquisitions Foundation 10 Knowledge and Research 32 Financial Statements 11 Publications 33 Financial Summary 12 Colloquia/Meetings 36 List of Donors and Partners 16 Exhibitions 2011/12 41 The Museum and its Team 21 Conservation OUR VISION OUR MISSION OUR THINKING OUR APPROACH The McCord Achievements An intelligent Contemporary Museum and themes that Museum that stirs and interactive; celebrates propel Montreal reflection. A immersive our past and onto the global current take on experiences. present lives— stage. An today’s issues, A Museum that our history, our openness to achievements extends outside people, our the world and and topics. its own walls, communities. issues important to the streets, to Montrealers the schools and and tourists. beyond. THEMcCORD MUSEUM MISSION ACCOMPLISHED! These words come Montreal and the Conseil des arts de Montréal. to mind spontaneously when I look back at the Sincere thanks as well to Sylvie Chagnon, who is year that ended March 31. Mission accomplished, stepping down from the McCord Museum Board because we ended the year with a surplus, and, as after many years, for her significant contribu- a result of our efforts, the Government of Quebec tions to the Museum on many levels. The McCord agreed to increase our annual operating grant. -

First Nations, Museums and Mccord Museum's Journey Acmss Borders Marketa Jarosova a Thesis in the Department of Art History Pres

First Nations, Museums and McCord Museum's Journey Acmss Borders Marketa Jarosova A Thesis in The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2001 8 Marketa Jarosova. 2001 Acquisitions and Acquisitiins et Bibliographie Services servicas bbiiiraphiques =w.phigtun- 395. nie Wslling(MI KlAW -ON K1A ON4 Cuiads Canada The author bas granteci a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lirary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationaie du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or seii reproduire, prêter, distrr'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electrooic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieis may be printed or otherwise de ceiieci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT First Nations, Museum and McCord Museum's Joumey Across Borders Marketa Jarosova f his thesis examines Native souvenir arts of the Novtheastern Woodlands and mirinclusion mincollections and exhibitions in Western museums. Since Western scholars have for the most part pereeived Native souvenir arts as inauthentic, these objects have nat only been exduded from &ous study, but Western museums have rarely exhibited them on a large scale. -

Liste Des Panneaux

Simply Montreal : Glimpses of a Unique City Complete texts of the exhibition presented at the McCord Museum. Permanent Exhibition Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Surviving Winter - Brrrr ! 5 1.1. Crossroads of the Winds 5 1.2. Below Zero 6 2. Surviving Winter - Cozy Mittens, Winterproof Walls 8 2.1. Second Skin 8 2.2. Warm and Cozy 11 2.3. Everyday Comfort 12 3. Surviving Winter - Montreal, Winter City 15 3.1. Getting Around 15 3.2. Ice for Sale 18 3.3. After the Storm 19 4. Different Cultures Meet - A Northern Mosaic 20 4.1. Montreal Portraits 20 4.2. A New Land 31 4.3. Migratory Waves 35 5. Different Cultures Meet - Living Together 37 5.1 Conflicts and Alliances 37 6. Different Cultures Meet - Alliances and Passions 43 6.1. Family Ties 43 6.2. Couples: Alliances and Passions 44 6.3. Garden of Cultures 46 7. Prospering - They Came from the Sea 53 7.1. Trading Routes 53 7.2. The Fur Rush 57 7.3. The Fur Barons 59 8. Prospering - City of Promise, Land of Trade 63 8.1. Commercial Hub 63 8.2. Place of Transit 66 8.3. At the Center of the Web 67 8.4. St. Catherine Street 69 9. Prospering - The Highs and Lows of an Imperial Jewel 73 9.1. The Wheels of Progress 73 9.2. A City of Contrasts 74 2 10. Enjoyment - From Cricket to Arm-wrestling 78 10.1. Something for Everyone 78 11. Enjoyment - Open-air City 82 11.1. -

2004-2005 Annual Report Ind Y Oi XV 19; Asca, 70; Rse Blnig O Er Jle (8210) Ky T History

2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 Annual Report › Growing Up in Montréal Our Mission Table of Contents The McCord Museum is a public research and teaching museum 2 Message from the Executive Director and Chair dedicated to the preservation, study, diffusion, and appreciation of 3 Financial Overview Canadian history. 3 The Year in Review Programming Excellence Grounded in its collections and the study of material culture, and Exhibitions in 2004-2005 building on the national vision of its founder, the McCord Museum 5 Acquisitions Highlights pursues excellence in research, collections, exhibitions, and 5 Research and Innovation education, using traditional media and innovative technologies and Awards and Recognition approaches to speak to contemporary preoccupations and to inspire 7 Involvement historical enquiry. 8 People Centre Support Our Vision The McCord Museum will become a world-renowned resource that inspires people to learn about the history of Canada and to reflect on our place in the world. McCord Museum of Canadian History 690 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 1E9 Phone: (514) 398-7100 Fax: (514) 398-5045 www.mccord-museum.qc.ca On the cover: Children running, David Hopkins, 1991; Mrs Miller’s children, Wm Notman & Son, 1890; teddy Jean Chagnon; George Carter and Judith Webster; Neil Putt. Pages 9-10, bottom: Anne MacKay; Denis Plourde; bear, 1900-1925; Mrs MacDougall’s children, Wm Notman & Son, 1915; Hon. Earnest Casgrain and grandchild, Erin Fraser. Centrefold, bottom front: visitors in Growing Up in Montréal; back: Julia and Stephen Reitman; Wm Notman & Son, 1914. Page 2, bottom left: caricature by Arthur G.