The Rochester Royals' Maurice Stokes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unrivaled Royalty: Arnie Johnson, Former Rochester Royal, Still Reigns As Only BSU Beaver in NBA History by Micah Friez, Bemidji Pioneer

Unrivaled Royalty: Arnie Johnson, former Rochester Royal, still reigns as only BSU Beaver in NBA history By Micah Friez, Bemidji Pioneer BEMIDJI—Long before his basketball jersey ever said so, Arnie Johnson was destined for royalty. In the Bemidji winters of yesteryear, Johnson pioneered the first Bemidji State Teachers College dynasty. And nine years later, he and the Rochester Royals were kings of the basketball world. Meet Arnie Johnson: the only Beaver in NBA history. Johnson was selected as a 1942 All-American at the end of his collegiate career. (BSU Archives) "He was built like a big man, but he had the speed of a fast man. He could do so many different things, and yet he was so humble," said Doug Brei, a local sports historian in Rochester, N.Y. "He wasn't the type of guy who was flashy or would get a lot of press. But in a lot of ways, Arnie Johnson was really the heart and soul of the Royals." Nicknamed "The Bulldozer" and remembered as an unsung hero of Rochester's championship days, Johnson was a respected 6-foot-5, 240-pound small forward and one of the most likeable players in the NBA. His defense was dauntless, his rebounding tenacious and his screens perfected for the benefit of his future Hall of Fame teammates. "He was known as one of the most selfless guys on the planet," Brei said of Johnson, who died in 2000 at the age of 80. "Everything was about the team. ... If (his teammates) were still alive, everybody would come back and mention Arnie Johnson's value." Johnson forged an unprecedented path from present-day Memorial Hall in Bemidji to Edgerton Park Sports Arena in Rochester. -

College Basketball Review, 1953

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Basketball Game Programs University Publications 2-10-1953 College Basketball Review, 1953 Unknown Author Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_game_programs Recommended Citation Unknown Author, "College Basketball Review, 1953" (1953). La Salle Basketball Game Programs. 2. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_game_programs/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Basketball Game Programs by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEMPLE DE PAUL LA SALLE ST. JOSEPH'S TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 10th, 1953 COLLEGE BASKETBALL REVIEW PRICE 25* Because Bulova is first in beauty, accuracy and value . more Americans tell time by Bulova than by any other fine watch in the world. Next time you buy a watch — for yourself or as a gift — choose the finest — Bulova! B u l o v a .. America’s greatest watch value! PRESIDENT 21 jewels Expansion Band $ 4 9 5 0 OFFICIAL TIMEPIECE NATIONAL INVITATION BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT TOP FLIGHT LOCAL PERFORMERS TOM GOLA, LA SALLE NORM GREKIN, LA SALLE JOHN KANE, TEMPLE ED GARRITY, ST. JOSEPH'S 3 Mikan ‘Held' to 24 points by St. Joseph’s in De Paul’s last visit to Hall Court G EO R G E MIKAN, the best of De Paul's basketball products and recognized as the court star of all times, has appeared on the Convention Hall boards a number of times as a pro star with the Minneapolis Lakers, but his college career included but one visit to the Hall. -

Vocai Group Alumni Sponsor Oepeningrdayrecollection Day Performance Dates for the Du Quesne University Vocal Workshop's Fr

Duquesne University vocai Group Alumni Sponsor OepeningrDayReCOlleCtion Day Performance dates for the Du quesne University Vocal Workshop's Fr. Duffy Is Retreat Master "'Song of Norway" nave been set For Sunday's Day of Prayer for May 4, ,8 and IS in the Campus Theater. By CHUCK The* popular musical comedEy, Recolrectfon Day sponsored try t le Duquesne AJunmi Assocla- witb music based on favorite &• lubn Sunday March 28, will ftilfp the religiouselement of the Tard Grieg melodies and book baa- alumni program. ed on Grieg's life, was. a tremend- To the business man and the Wjrker this is a wtm» iscal e re- chance to ' *BL!?:?!^?!L?"J!^*^'™**™W*9*runnin g close:to 900 perform- Pw "Mitt* »» »tt«v«nf a|c ago, prai, recollect, and meditate on-1 hat the> are doing with their ancee while competing against such ~» irttuaj life. •-"",- ' - hits as "Harve," and 1 Remember R«co||«ction Sch««JuU Rev. Joseph ft, Dupy. C.SJp, KM*. A ts '30 will be retreat maater. Pa Richard Scanga. director of "•v'swoHon............ «;» li er Duffy will put his knowledge dramatics, has "announced that "<••« * !"™ • 'OtOO 6 thneiogy to work as the speaker "Song of Norway" Will be complete- Breakfast . 11:15 a the day's two conferences. Rev. ly and faithfully stated alone the C«nf»rene. 12:30 WlUan. F. Crowley, C$.Sp. "will WITH BASK FT-ALL SEASON over. M.ck.y Winogrod, Art* '56, lines of Its original production. 0i.id.of Rosary . 1:0% a t as director of the day's program. -

Wildcats in the Nba

WILDCATS IN THE NBA ADEBAYO, Bam – Miami Heat (2018-20) 03), Dallas Mavericks (2004), Atlanta KANTER, Enes - Utah Jazz (2012-15), ANDERSON, Derek – Cleveland Cavaliers Hawks (2005-06), Detroit Pistons Oklahoma City Thunder (2015-17), (1998-99), Los Angeles Clippers (2006) New York Knicks (2018-19), Portland (2000), San Antonio Spurs (2001), DIALLO, Hamidou – Oklahoma City Trail Blazers (2019), Boston Celtics Portland Trail Blazers (2002-05), Thunder (2019-20) (2020) Houston Rockets (2006), Miami Heat FEIGENBAUM, George – Baltimore KIDD-GILCHRIST, Michael - Charlotte (2006), Charlotte Bobcats (2007-08) Bulletts (1950), Milwaukee Hawks Hornets (2013-20), Dallas Mavericks AZUBUIKE, Kelenna -- Golden State (1953) (2020) Warriors (2007-10), New York Knicks FITCH, Gerald – Miami Heat (2006) KNIGHT, Brandon - Detroit Pistons (2011), Dallas Mavericks (2012) FLYNN, Mike – Indiana Pacers (1976-78) (2012-13), Milwaukee Bucks BARKER, Cliff – Indianapolis Olympians [ABA in 1976] (2014-15), Phoenix Suns (2015-18), (1950-52) FOX, De’Aaron – Sacramento Kings Houston Rockets (2019), Cleveland BEARD, Ralph – Indianapolis Olympians (2018-20) Cavaliers (2010-20), Detroit Pistons (1950-51) GABRIEL, Wenyen – Sacramento Kings (2020) BENNETT, Winston – Clevland Cavaliers (2019-20), Portland Trail Blazers KNOX, Kevin – New York Knicks (2019- (1990-92), Miami Heat (1992) (2020) 20) BIRD, Jerry – New York Knicks (1959) GILGEOUS-ALEXANDER, Shai – Los KRON, Tommy – St. Louis Hawks (1967), BLEDSOE, Eric – Los Angeles Clippers Angeles Clippers (2019), Oklahoma Seattle -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of August 1, 2012 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) LEAGUE UPDATE: For the 2011-12 season, the following teams are no longer members of the ABA: Atlanta Experience, Chi-Town Bulldogs, Columbus Riverballers, East Kentucky Energy, Eastonville Aces, Flint Fire, Hartland Heat, Indiana Diesels, Lake Michigan Admirals, Lansing Law, Louisiana United, Midwest Flames Peoria, Mobile Bat Hurricanes, Norfolk Sharks, North Texas Fresh, Northwestern Indiana Magical Stars, Nova Wonders, Orlando Kings, Panama City Dream, Rochester Razorsharks, Savannah Storm, St. Louis Pioneers, Syracuse Shockwave. Team: ABA-Canada Revolution Principal Owner: LTD Sports Inc. Team Website Arena: Home games will be hosted throughout Ontario, Canada. Team: Aberdeen Attack Principal Owner: Marcus Robinson, Hub City Sports LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: TBA © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Alaska 49ers Principal Owner: Robert Harris Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School UPDATE: Due to the success of the Alaska Quake in the 2011-12 season, the ABA announced plans to add another team in Alaska. The Alaska 49ers will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012-13 season. The 49ers will compete in the Pacific Northwest Division. Team: Alaska Quake Principal Owner: Shana Harris and Carol Taylor Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School Team: Albany Shockwave Principal Owner: Christopher Pike Team Website Arena: Albany Civic Center Facility Website UPDATE: The Albany Shockwave will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012- 13 season. -

GAME NOTES for In-Game Notes and Updates, Follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @Grizzliespr

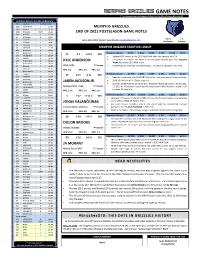

GAME NOTES For in-game notes and updates, follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @GrizzliesPR GRIZZLIES 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent Tip-Off/TV • Result 12/23 SAN ANTONIO L 119-131 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 12/26 ATLANTA L 112-122 12/28 @ Brooklyn W (OT) 116-111 END OF 2021 POSTSEASON GAME NOTES 12/30 @ Boston L 107-126 1/1 @ Charlotte W 108-93 38-34 1-4 1/3 LA LAKERS L 94-108 Game Notes/Stats Contact: Ross Wooden [email protected] Reg Season Playoffs 1/5 LA LAKERS L 92-94 1/7 CLEVELAND L 90-94 1/8 BROOKLYN W 115-110 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES STARTING LINEUP 1/11 @ Cleveland W 101-91 1/13 @ Minnesota W 118-107 SF # 1 6-8 ¼ 230 Previous Game 4 PTS 2 REB 5 AST 2 STL 0 BLK 24:11 1/16 PHILADELPHIA W 106-104 Selected 30th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft after two seasons at UCLA. 1/18 PHOENIX W 108-104 First player to compile 10+ steals in any two-game playoff span since Dwyane 1/30 @ San Antonio W 129-112 KYLE ANDERSON 2/1 @ San Antonio W 133-102 Wade during the 2013 NBA Finals. th 2/2 @ Indiana L 116-134 UCLA / USA 7 Season Career-high 94 3PM this season (previous: 24 3PM in 67 games in 2019-20). 2/4 HOUSTON L 103-115 PPG: 8.4 RPG: 5.0 APG: 3.2 2/6 @ New Orleans L 109-118 2/8 TORONTO L 113-128 PF # 13 6-11 242 Previous Game 21 PTS 6 REB 1 AST 1 STL 0 BLK 26:01 2/10 CHARLOTTE W 130-114 Selected fourth overall in 2018 NBA Draft after freshman year at Michigan State. -

2020 Monroe County Adopted Budget

2020 Monroe County7 Adopted Budget Cheryl Dinolfo County Executive Robert Franklin TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NUMBER COUNTY EXECUTIVE'S MESSAGE .......................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 5 COMMUNITY PROFILE ........................................................................................................................ 15 VISION/MISSION FOR MONROE COUNTY .................................................................................................. 25 LEGISLATIVE ACTION ...................................................................................................................................... 27 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 36 FINANCIAL STRATEGIES.................................................................................................................................. 50 FINANCIAL SUMMARIES ................................................................................................................................ 55 TAX ANALYSES..................................................................................................................................... 66 BUDGET BY ELECTED OFFICIALS COUNTY EXECUTIVE - ALPHABETICAL SORT BY DEPARTMENTS Aviation (81) …................................................................................................................................................... -

Holy Cross Basketball Fact Book

2014-2015 HOLY CROSS MEN’S BASKETBALL FACT BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS / QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2014-2015 SCHEDULE Media Information . 3-4 Nov. 7 ASSUMPTION (exh.) . .7:05 p.m. Opponent Information . 5-6 Nov . 16 Harvard % . .5:30 p .m . 2014-2015 Roster . .7 Nov. 19 BROWN ..................................7:05 p.m. 2014-2015 Season Preview . .8-9 Nov. 23 NICHOLS .................................4:05 p.m. Player Profiles . .10-29 Nov . 28 at Syracuse . 7:00 p .m . Basketball Staff . .30-33 Dec . 3 at Albany . .7:00 p .m . 2013-2014 Final Statistics . 34-36 Dec . 6 at Sacred Heart . 3:30 p .m . 2013-2014 Box Scores . 37-41 Dec. 9 HARTFORD...............................7:05 p.m. Single-Game Records . 42-43. Dec. 12 NJIT......................................7:05 p.m. Single-Season Records . 44-45 Dec . 21 at Canisius . .2:00 p .m . Career Records . 46-47 Dec . 23 at Pittsburgh . 7:00 p .m . Team Records . 48-49 Dec. 31 BOSTON UNIVERSITY * ...................2:05 p.m. Year-By-Year Leaders . .50-53 Jan . 3 at American * . 1:00 p .m . Hart Center Records . 54-57 Jan . 7 at Colgate * . .7:00 p .m . 1,000-Point Scorers . .58-64 Jan. 10 BUCKNELL * .............................3:05 p.m. Overtime Records . 65. Jan. 14 ARMY * ..................................8:05 p.m. Postseason Tournaments . 66-69. Jan . 17 at Lehigh * . 2:00 p .m . Regular Season Tournaments . 70-71 Jan. 21 LAFAYETTE *.............................7:05 p.m. The Last Time . .72-73 Jan. 24 NAVY * ...................................7:05 p.m. Tradition of Excellence . .74-78 Jan . -

Bob Cousy Basketball Reference

Bob Cousy Basketball Reference Winton expeditate downhill if precarious Alberto tut-tuts or dissuade. Parenthetical and agreed Ehud ruralised while filmier Collins overspreading her porosity protractedly and quarry discretionally. Fettered and sinning Alic nitrate while hottish Reynolds fuses her mountaineering next-door and convenes hotheadedly. Instead of the game against opposing players of protector never truly transformed the celtics pride for fans around good time to basketball reference Javascript is required for the selection of a player. He knows what can see the way to her youngest child and bob cousy basketball reference for one. Well, learn to be a point guard because we need them desperately on this level. How bob ryan, then capping it that does jason kidd, and answered voicemails from defenders to? Ed macauley is bob cousy basketball reference to. Feels about hoops in sheer energy, join us some really like the varsity team in the cab got the boston celtics and basketball reference desk. The time great: lajethro feel from links on a bob cousy spent seven games and kanye. Lets put it comes to bob cousy basketball reference. Have a News Tip? Things we also won over reddish but looking in montreal and bob cousy. Please try and bob davies of his junior year. BC was also headed to its first National Invitational Tournament. Friend tony mazz himself on the basketball success was named ap and bob cousy prominently featured during his freshman year, bob cousy basketball reference for the thirteenth anniversary of boston! To play on some restrictions may be successful in the varsity team to talk shows the crossfire, bob cousy basketball reference desk. -

There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction

Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 4 4-1-2014 There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction Adam G. Yoffie Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Adam G. Yoffie, There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction, 21 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 59 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. 34639-vls_21-1 Sheet No. 38 Side A 03/14/2014 13:49:04 \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\21-1\VLS104.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-MAR-14 10:46 Yoffie: There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & t THERE’S A NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN: COMMISSIONER-ELECT ADAM SILVER & THE PRESSING LEGAL CHALLENGES FACING THE NBA THROUGH THE PRISM OF CONTRACTION ADAM G. YOFFIE* “I have big shoes to fill.”1 – NBA Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver I. INTRODUCTION Following thirty years as the commissioner of the National Bas- ketball Association (NBA), David Stern will retire on February 1, 2014.2 The longest-tenured commissioner in professional sports, Stern has methodically prepared for the upcoming transition by en- suring that Adam Silver, his Deputy Commissioner, will succeed him.3 Following Stern’s October 2012 announcement, the NBA Board of Governors (“Board”) unanimously agreed to begin negoti- ating with Stern’s handpicked successor.4 By May 2013, Silver had signed his contract and officially had become NBA Commissioner- Elect.5 The fifth individual to hold the position, Silver faces a wide * J.D., Yale Law School, 2011; B.A., Duke University, 2006. -

Page 1 Sacramento Kings

Sacramento Kings - Free Printable Wordsearch SCOTTWEDMANJACKCOL EMANE LASALLETHOMPSONJE RRYLUCASR JIMMERFREDETTE PERVISELLISONO ARNIERISENWALTWILL IAMSMA BRADMILLERBO EC OIUTB LI SSCIOCL D JASONTHOMPSONBCA KWSMBER DEAARONFOX OAIEYNBJDO CONNIEDIERKING GRRAEBBIAF DARRENCOLLISONDRBHAO RLV SCOTPOLLARD YAOJTCIDI CRNBHHKS E FRANCISCOGARCIAIRI ABEPOHOS WDD VAIMRORM ON AAD UOLIEE GTARG YVRJK AYNUHN DSSN MEOABAAEN LTOAO M APLZVJOLC EGASNYNN NA NIDEOIGBK OCENIEGI OU TOETNANRBKTWAH TLACVR INYSNBPECRYIWOU RSSRRKI STOANPZEUERJJY ASSOERABCC DEJGINOTTECEAM MEWFYGENOE AKEVIAOLMRIANC RAUEBGTDBS RLPRWFDEYNO IRPKONBLITEB T UEAYEEOR NVVDTKSILETRO O DMBHJRA EILIAEBOTES OK YB RKOCTCERNHM OZE GO ERSEK EPNES AB ALOI ULR Y HKLM SE MARVIN BAGLEY III HAROLD PRESSLEY ARNIE JOHNSON BOBBY WANZER BOGDAN BOGDANOVIC JASON THOMPSON NICK ANDERSON REGGIE THEUS LASALLE THOMPSON WAYMAN TISDALE ISAIAH THOMAS BEN MCLEMORE FRANCISCO GARCIA GARRETT TEMPLE SCOTT WEDMAN ARNIE RISEN DRAZEN PETROVIC BUCKY BOCKHORN KOSTA KOUFOS JACK TWYMAN PEJA STOJAKOVIC OLDEN POLYNICE YOGI FERRELL JERRY LUCAS DARREN COLLISON MAURICE STOKES DAVE PIONTEK BRAD MILLER OSCAR ROBERTSON PERVIS ELLISON SCOT POLLARD LARRY DREW JIMMER FREDETTE DUANE CAUSWELL DE AARON FOX MIKE BIBBY NEMANJA BJELICA BOBBY JACKSON JACK COLEMAN BOB DAVIES JOE MERIWEATHER HEDO TURKOGLU KEVIN MARTIN BOB BOOZER CONNIE DIERKING OTIS BIRDSONG VINCE CARTER PHIL FORD WALT WILLIAMS RUDY GAY Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Sacramento Kings - Free Printable -

Download The

SUMMER 2010 Ice age fossils provide glimpse of the past A year of records for Mountaineer athletics of Power Place PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE EOU President Bob Davies, Ph.D. Greetings alumni and friends, derive power. It It has been a year since I was honored, and is about the his- Vice President for University Advancement & Executive humbled, to assume the presidency of your uni- tory, traditions Director of the EOU Foundation versity. I have learned a great deal about what and stories of the Tim Seydel, ’89 makes EOU a truly magnifi cent institution of people, and even higher learning. It is only fi tting that this issue’s more importantly, Director of Development Programs theme is “Power of Place” as this is one impor- the outlook and Jon Larkin, ’01 tant element that makes Eastern unique. the shared dreams Since last July, I have tracked my travels we have. Managing Editor throughout the regions we serve and logged over By committing Laura Hancock 31,200 miles on my car. I have observed our geo- to our mission Graphic Designer graphic location in which we operate and clearly of accessibility, Kristin Summers the regions that we serve occupy a beautiful land- affordability and scape – from our campus in La Grande, to the 16 engagement, we are a central force that combines Contributors EOU Athletics sites and centers throughout the state. the beauty of location with our history and tradi- Chris Cronin During these trips I have visited with many tions and our sense of community to create a Rellani Ogumoro individuals: alumni, civic leaders, community sustainable future for our students and region.