Case 8:17-Cv-01596-PJM Document 21 Filed 09/29/17 Page 1 of 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: the Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 27 Issue 5 Article 7 1982 Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles James McClellan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation James McClellan, Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles, 27 Vill. L. Rev. 1019 (1982). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol27/iss5/7 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McClellan: Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect 1981-82] CONGRESSIONAL RETRACTION OF FEDERAL COURT JURISDICTION TO PROTECT THE RESERVED POWERS OF THE STATES: THE HELMS PRAYER BILL AND A RETURN TO FIRST PRINCIPLES JAMES MCCLELLAN t S INCE THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THE WARREN COURT, countless bills have been introduced in Congress which would deny the federal courts jurisdiction over a great variety of subjects ranging from busing to abortion.' The exceptions clause of article III of the Constitution provides Congress with the authority to enact such bills. 2 While none of these proposed bills has been enacted into law, it is noteworthy that two have passed at least one house of Congress, and that both of these have sought to deny all federal courts, including the Supreme Court, jurisdiction over certain cases arising under the fourteenth amendment. -

Leseprobe 9783791384900.Pdf

NYC Walks — Guide to New Architecture JOHN HILL PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAVEL BENDOV Prestel Munich — London — New York BRONX 7 Columbia University and Barnard College 6 Columbus Circle QUEENS to Lincoln Center 5 57th Street, 10 River to River East River MANHATTAN by Ferry 3 High Line and Its Environs 4 Bowery Changing 2 West Side Living 8 Brooklyn 9 1 Bridge Park Car-free G Train Tour Lower Manhattan of Brooklyn BROOKLYN Contents 16 Introduction 21 1. Car-free Lower Manhattan 49 2. West Side Living 69 3. High Line and Its Environs 91 4. Bowery Changing 109 5. 57th Street, River to River QUEENS 125 6. Columbus Circle to Lincoln Center 143 7. Columbia University and Barnard College 161 8. Brooklyn Bridge Park 177 9. G Train Tour of Brooklyn 195 10. East River by Ferry 211 20 More Places to See 217 Acknowledgments BROOKLYN 2 West Side Living 2.75 MILES / 4.4 KM This tour starts at the southwest corner of Leonard and Church Streets in Tribeca and ends in the West Village overlooking a remnant of the elevated railway that was transformed into the High Line. Early last century, industrial piers stretched up the Hudson River from the Battery to the Upper West Side. Most respectable New Yorkers shied away from the working waterfront and therefore lived toward the middle of the island. But in today’s postindustrial Manhattan, the West Side is a highly desirable—and expensive— place, home to residential developments catering to the well-to-do who want to live close to the waterfront and its now recreational piers. -

Three Federalisms Randy E

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2007 Three Federalisms Randy E. Barnett Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/23 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers THREE FEDERALISMS RANDY E. BARNETT* ABSTRACT: Debates over the importance of “federalism” are often obscured by the fact that there are not one, but three distinct versions of constitutional federalism that have arisen since the Founding: Enumerated Powers Federalism in the Founding era, Fundamental Rights Federalism in the Reconstruction era, and Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism in the post-New Deal era. In this very short essay, my objective is to reduce confusion about federalism by defining and identifying the origin of each of these different conceptions of federalism. I also suggest that, while Fundamental Rights Federalism significantly qualified Enumerated Powers Federalism, it was not until the New Deal’s expansion of federal power that Enumerated Powers Federalism was eviscerated altogether. To preserve some semblance of state discretionary power in the post-New Deal era, the Rehnquist Court developed an ahistorical Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism that was both under- and over-inclusive of the role of federalism that is warranted by the original meaning of the Constitution as amended. In my remarks this morning, I want to explain how there are, not one, but three distinct versions of federalism that have developed since the Founding. -

History SS Federalism Today Complex Project

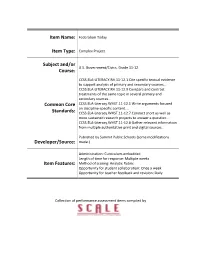

Item Name: Federalism Today Item Type: Complex Project Subject and/or U.S. Government/Civics, Grade 11-12 Course: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources… CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources… Common Core CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content…. Standards: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.7 Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question… CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources… Published by Summit Public Schools (some modifications Developer/Source: made.) Administration: Curriculum-embedded Length of time for response: Multiple weeks Item Features: Method of scoring: Analytic Rubric Opportunity for student collaboration: Once a week Opportunity for teacher feedback and revision: Daily Collection of performance assessment items compiled by Overview This learning module will prepare you to write an argument over which level of government, federal or state, should have the authority and power when making and executing laws on controversial issues. You will research an issue of your choice, write an argument in support of your position, and then present it to a panel of judges. Standards AP Standards: APS.SOC.9-12.I Constitutional Underpinnings of United States Government APS.SOC.9-12.I.D - Federalism Objective: Understand the implication(s) -

Federalism in the Constitution

Federalism in the Constitution As you read each paragraph, answer the questions in the margin. The United States is one country—but it’s also a bunch of states. You When creating the Constitution, what could almost say it’s a group of states that are, well, united. When we things did we need our central created the Articles of Confederation, each state already had its own government to be able to do? government and court system, so the new Americans weren’t exactly running amok. But if the new United States was going to be able to deal with other nations, it needed one government that would speak for the entire country. It also needed one central government to do things like declare war on other countries, keep a military, and negotiate treaties with other countries. There also needed to be federal courts where citizens from different states could resolve their disputes. So, the Founders created the Constitution to do those things. Define federalism. The United States Constitution created a central government known as the federal government. The federal government deals with issues that affect the entire country. Each state also has its own state government that only handles the affairs of that state. This division of power between a central government and state governments is called federalism. The federal government gets all of its power from the Create a Venn Diagram, with labels, that shows Constitution. These federal powers are listed in the the relationship between the federal powers, Constitution. In order to keep the federal government from reserve powers, and concurrent powers. -

Golf Courses + Resorts Owned & Managed by TRUMP Domestic

Golf Courses + Resorts Owned & Managed by TRUMP Domestic: Trump International Golf Club, Palm Beach Trump National Golf Club, Jupiter Trump National Golf Club, Washington D.C. Trump National Doral, Miami (Hotel + Golf) Trump National Golf Club, Colts Neck Trump National Golf Club, Westchester Trump National Golf Club, Hudson Valley Trump National Golf Club, Bedminster Trump National Golf Club, Philadelphia Trump National Golf Club, Los Angeles Trump National Golf Club, Charlotte International: Trump International Golf Links, Aberdeen (Hotel + Golf) Trump International Golf Links & Hotel, Doonbeg, Ireland (Hotel + Golf) Trump Turnberry (Hotel + Golf) Golf Courses Developed + Managed by TRUMP Trump Golf Links at Ferry Point Golf Courses Managed by TRUMP Trump International Golf Club, Dubai Trump World Golf Club, Dubai Indonesia – Coming Soon Hotel Properties Owned & Managed by TRUMP Trump International Golf Links, Aberdeen (Hotel + Golf) Trump International Golf Links & Hotel, Doonbeg, Ireland (Hotel + Golf) Trump National Doral, Miami (Hotel + Golf) Trump Turnberry (Hotel + Golf) The Albemarle Estate at Trump Winery (Hotel) Trump International Hotel & Tower New York Trump International Hotel & Tower Chicago Trump International Hotel, Washington D.C. Hotel Properties Owned in Partnership & Managed by TRUMP Trump International Hotel Las Vegas – Partners with Phil Ruffin Hotel Properties Managed by TRUMP Trump SoHo New York Trump International Hotel & Tower Toronto Trump Ocean Club, Panama Trump International Hotel & Tower Vancouver – Coming -

Constitutional Uncertainties from Presidential Tax Return Release Laws

Releasing the 1040, Not so EZ: Constitutional Uncertainties from Presidential Tax Return Release Laws# Matthew M. Ryan* Introduction ............................................................................................ 209 I. U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton ..................................................... 211 II. What is a Qualification? ..................................................................... 212 A. Targeting a Class of Candidates .......................................... 212 B. Impermissibly Barring or Hindering Candidacy .................. 213 III. The Protection of Informational Privacy .......................................... 213 IV. Anti-Corruption Interest: Emoluments Clauses ................................ 216 V. State Power in Presidential Elections ................................................. 217 VI. Slippery Slope .................................................................................. 220 INTRODUCTION On multiple fronts, Americans are pursuing President Trump’s tax returns: a senator through legislation, a district attorney and congressional committees through investigation, and voters through protest and persuasion.1 None have succeeded. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KK94C89. Copyright © 2020 Matthew M. Ryan. # An extended version of this Article can be found in the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly. See Matthew M. Ryan, Releasing the 1040, Not so EZ: Constitutional Ambiguities Raised by State Laws Mandating Tax Return Release for Presidential Candidates, 47 HASTINGS CONST. -

Revised June 7, 2017 Andy Pagel and Shannon Meulbroek Two Rivers

PO Box 716, Menomonie, WI 54751 715-231-4025 Office / 715-231-4026 Fax 844-590-9765 Toll Free / zbesttours @ gmail.com May 17, 2017; Revised June 7, 2017 Andy Pagel and Shannon Meulbroek Two Rivers High School Band and Choir 4519 Lincoln Avenue Two Rivers, WI 54241 Dear Andy and Shannon, The following is the itinerary for your trip to New York City from June 19 to 24, 2017. This itinerary is subject to change based on availability and some of the times listed are approximate. Monday, June 19, 2017 7:00 AM Buses (3) arrive at High School 7:30 AM Depart Two Rivers High School TBD Rest stops and meals on your own en route NOTE: TIME ZONE CHANGE OCCURS Tuesday, June 20, 2017 5:30 AM Arrive at Rockefeller Center Change clothes and get ready for the day 6:30 AM Line up for the Today Show 7:00 AM Today Show 9:00 AM Step-on Guided New York City Tour Includes: Ground Zero, China Town, Battery Park, Chelsea, Greenwich Village, Tribeca, Mid Town, Grand Central Station (Meet guides near the Today Show and NBC Store on West 49th Street between 5th & 6th Avenues; End at Battery Park at 1:00 PM) Lunch on your own 2:00 PM Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue 5:00 PM Depart the Museum 5:30 PM Dallas BBQ, 241 West 42nd Street 7:00 PM Depart for the hotel 8:00 PM Check into the LaQuinta Inn and Suites 350 Lighting Way, Secaucus, New Jersey 10:00 PM Lights Out / Night Time Security Wednesday, June 21, 2017 6:15 AM Breakfast at the hotel (stagger in groups at 6:15, 6:45, and 7:15 AM) 8:00 AM Depart the hotel 1:00 PM Free Time in Central Park and Fifth Avenue; Lunch on your own PO Box 716, Menomonie, WI 54751 715-231-4025 Office / 715-231-4026 Fax 844-590-9765 Toll Free / zbesttours @ gmail.com Carriage Rides, Strawberry Fields, Shopping, Tiffany’s, Trump Tower, H&M, etc. -

730 Fifth Avenue

730 Fifth Avenue LUXURY RETAIL OPPORTUNITY SPRING 2018 - 3 - 730 Fifth Avenue A LOCATION LIKE NO OTHER The Crown Building offers a flagship opportunity at the most prestigious corner in the world. Fifth Avenue and 57th Street is the crossroads of the Plaza District, Billionaires’ Row, and the Fifth Avenue Luxury Retail Corridor. This location is surrounded by New York’s premier Class A office buildings, four diamond hotels, world-class restaurants and upscale residential towers. · 200,000 pedestrians per day · 40,000,000 people visit area per year · $4 Billion in Annual Sales on Fifth Avenue Corridor - 4 - CENTRAL PARK A LA VIEILLE RUSSIE 59TH ST THE RITZ-CARLTON THE PLAZA HOTEL 58TH ST BERGDORF GOODMAN VAN CLEEF & ARPELS BERGDORF GOODMAN FENDI 57TH ST COMING SOON MIKIMOTO TRUMP TOWER ABERCROMBIE AND FITCH 56TH ST GIORIO ARMANI FIFTH AVENUE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 55TH ST PENINSULA HOTEL WEMPE 730 Fifth Avenue FIFTH AVENUE LINDT 54TH ST CONTEXT MAP 53RD ST 52ND ST COMING SOON VICTORIA’S SECRET 51ST ST ROCKEFELLER CENTER ST. PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL 50TH ST COLE HAAN ROCKEFELLER CENTER 49TH ST ROCKEFELLER CENTER - 5 - 730 Fifth Avenue CONCEPTUAL RENDERING - 6 - THIRD LEVEL 22,279 SF SECOND LEVEL 23,462 SF 730 Fifth Avenue CONCEPTUAL PLAN MEZZANINE LEVEL APPROXIMATE FLOOR-TO-FLOOR HEIGHTS 3,428 SF (EXPANDABLE) CELLAR LEVEL 12’-1” STREET LEVEL 10’ / 20’ MEZZANINE LEVEL 10’-0” SECOND LEVEL 14’-0” THIRD LEVEL 12’-10” STREET LEVEL 17,801 SF TOTAL SQUARE FOOTAGE 77,053 SF 3rd 2nd MEZZANINE STREET CELLAR LEVEL ENTRANCES 10,083 SF ENTRANCES FIFTH AVENUE th STREET C O NFID E NTI AL O FFE57RIN G MEM O R A N D U M * Plans and square footage are conceptual and will need additional verification. -

DONALD TRUMP REFLECTS on HIS BEGINNINGS, VENTURES, and PLANS for the FUTURE Donald Trump Chairman and President the Trump Organ

DONALD TRUMP REFLECTS ON HIS BEGINNINGS, VENTURES, AND PLANS FOR THE FUTURE Donald Trump Chairman and President The Trump Organization December 15, 2014 Excerpts from Mr. Trump's Remarks Are you considering running for President? I am considering it very strongly. How did you get started in business, buying a hotel, with almost no money? Well, it was owned by the Penn Central Railroad and it was run by some very good people. Actually, it's very interesting, because he happens to be a very good man. It was Victor Palmieri and Company. And one of the people is John Koskinen. Does anyone know John Koskinen? He's the head of the IRS. And he's a very good man. And while I'm a strong conservative and a strong Republican, he's a friend of mine. And he did a great job running Victor Palmieri. And I made deals with John and the people at Victor Palmieri and took options to the building. And after I took options to the Commodore, I then went to the city. Because the city was really in deep trouble. I was about 28 years old, and the city was really in trouble. And I said look, you're going to have to give me tax abatement. Otherwise this was never going to happen. Then I went to Hyatt. I said you guys put up all the money and I'll try and get the approvals. And I got all the approvals. And Hyatt, Jay Pritzker and the Pritzker family, they put up the money. -

Arrive a Tourist. Leave a Local

TOURS ARRIVE A TOURIST. LEAVE A LOCAL. www.OnBoardTours.com Call 1-877-U-TOUR-NY Today! NY See It All! The NY See It All! tour is New York’s best tour value. It’s the only comprehensive guided tour of shuttle with you at each stop. Only the NY See It All! Tour combines a bus tour and short walks to see attractions with a boat cruise in New York Harbor.Like all of the NYPS tours, our NY See It All! Our guides hop o the shuttle with you at every major attraction, including: START AT: Times Square * Federal Hall * World Trade Ctr. Site * Madison Square Park * NY Stock Exchange * Statue of Liberty * Wall Street (viewed from S. I. Ferry) * St. Paul’s Chapel * Central Park * Trinity Church * Flatiron Building * World Financial Ctr. * Bowling Green Bull * South Street Seaport * Empire State Building (lunch cost not included) * Strawberry Fields * Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick's Cathedral In addition, you will see the following attractions along the way: (we don’t stop at these) * Ellis Island * Woolworth Building * Central Park Zoo * Met Life Building * Trump Tower * Brooklyn Bridge * Plaza Hotel * Verrazano-Narrows Bridge * City Hall * Hudson River * Washington Square Park * East River * New York Public Library * FAO Schwarz * Greenwich Village * Chrysler Building * SOHO/Tribeca NY See The Lights! Bright lights, Big City. Enjoy The Big Apple aglow in all its splendor. The NY See The Lights! tour shows you the greatest city in the world at night. Cross over the Manhattan Bridge and visit Brooklyn and the Fulton Ferry Landing for the lights of New York City from across the East river. -

Factors Determining the Success of Congressional Efforts to Reverse Supreme Court Interpretations of the Constitution

William & Mary Law Review Volume 33 (1991-1992) Issue 2 Article 6 February 1992 Looking Down From the Hill: Factors Determining the Success of Congressional Efforts to Reverse Supreme Court Interpretations of the Constitution Mark E. Herrmann Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Juvenile Law Commons Repository Citation Mark E. Herrmann, Looking Down From the Hill: Factors Determining the Success of Congressional Efforts to Reverse Supreme Court Interpretations of the Constitution, 33 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 543 (1992), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol33/iss2/6 Copyright c 1992 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr LOOKING DOWN FROM THE HILL: FACTORS DETERMINING THE SUCCESS OF CONGRESSIONAL EFFORTS TO REVERSE SUPREME COURT INTERPRETATIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION That there ought to be one court of supreme and final juris- diction, is a proposition which is not likely to be contested.... A legislature, without exceeding its province, cannot reverse a determination once made in a particular case; though it may prescribe a new rule for future cases.' Throughout the 200-year history of the United States Consti- tution, frequent debate has arisen over the proper roles of the three branches of the federal government in interpreting the Constitution. The Supreme Court has, in recent years, expressed the view that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law under the Constitution. 2 Under this view, once the Supreme Court has spoken regarding a constitutional issue, only the Court itself can alter that interpretation of the Constitution.