Arxiv:1710.07379V2 [Gr-Qc] 31 Jul 2021 Area Deficits and the Bel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

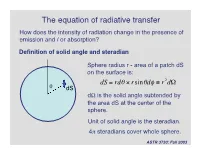

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Area of Polygons and Complex Figures

Geometry AREA OF POLYGONS AND COMPLEX FIGURES Area is the number of non-overlapping square units needed to cover the interior region of a two- dimensional figure or the surface area of a three-dimensional figure. For example, area is the region that is covered by floor tile (two-dimensional) or paint on a box or a ball (three- dimensional). For additional information about specific shapes, see the boxes below. For additional general information, see the Math Notes box in Lesson 1.1.2 of the Core Connections, Course 2 text. For additional examples and practice, see the Core Connections, Course 2 Checkpoint 1 materials or the Core Connections, Course 3 Checkpoint 4 materials. AREA OF A RECTANGLE To find the area of a rectangle, follow the steps below. 1. Identify the base. 2. Identify the height. 3. Multiply the base times the height to find the area in square units: A = bh. A square is a rectangle in which the base and height are of equal length. Find the area of a square by multiplying the base times itself: A = b2. Example base = 8 units 4 32 square units height = 4 units 8 A = 8 · 4 = 32 square units Parent Guide with Extra Practice 135 Problems Find the areas of the rectangles (figures 1-8) and squares (figures 9-12) below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 2 mi 5 cm 8 m 4 mi 7 in. 6 cm 3 in. 2 m 5. 6. 7. 8. 3 units 6.8 cm 5.5 miles 2 miles 8.7 units 7.25 miles 3.5 cm 2.2 miles 9. -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

The American Society of Echocardiography

1 THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CARDIAC CHAMBER QUANTIFICATION IN ADULTS: A QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE FROM THE ASE WORKFLOW AND LAB MANAGEMENT TASK FORCE Accurate and reproducible assessment of cardiac chamber size and function is essential for clinical care. A standardized methodology creates a common approach to the assessment of cardiac structure and function both within and between echocardiography labs. This facilitates better communication and improves the ability to compare results between studies as well as differentiate normal from abnormal findings in an individual patient. This document summarizes key points from the 2015 ASE Chamber Quantification Guideline and is meant to serve as quick reference for sonographers and interpreting physicians. It is designed to provide guidance on chamber quantification for adult patients; a separate ASE Guidelines document that details recommended quantification methods in the pediatric age group has also been published and should be used for patients <18 years of age (3). (1) For details of the methodology and the rationale for current recommendations, the interested reader is referred to the complete Guideline statement. Figures and tables are reproduced from ASE Guidelines. (1,2) Table of Contents: 1. Left Ventricle (LV) Size and Function p. 2 a. LV Size p. 2 i. Linear Measurements p. 2 ii. Volume Measurements p. 2 iii. LV Mass Calculations p. 3 b. Left Ventricular Function Assessment p. 4 i. Global Systolic Function Parameters p. 4 ii. Regional Function p. 5 2. Right Ventricle (RV) Size and Function p. 6 a. RV Size p. 6 b. RV Function p. 8 3. Atria p. -

Difference Between Angular Momentum and Pseudoangular

Difference between angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum Simon Streib Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 516, SE-75120 Uppsala, Sweden (Dated: March 16, 2021) In condensed matter systems it is necessary to distinguish between the momentum of the con- stituents of the system and the pseudomomentum of quasiparticles. The same distinction is also valid for angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum. Based on Noether’s theorem, we demonstrate that the recently discussed orbital angular momenta of phonons and magnons are pseudoangular momenta. This conceptual difference is important for a proper understanding of the transfer of angular momentum in condensed matter systems, especially in spintronics applications. In 1915, Einstein, de Haas, and Barnett demonstrated experimentally that magnetism is fundamentally related to angular momentum. When changing the magnetiza- tion of a magnet, Einstein and de Haas observed that the magnet starts to rotate, implying a transfer of an- (a) gular momentum from the magnetization to the global rotation of the lattice [1], while Barnett observed the in- verse effect, magnetization by rotation [2]. A few years later in 1918, Emmy Noether showed that continuous (b) symmetries imply conservation laws [3], such as the con- servation of momentum and angular momentum, which links magnetism to the most fundamental symmetries of nature. Condensed matter systems support closely related con- Figure 1. (a) Invariance under rotations of the whole system servation laws: the conservation of the pseudomomentum implies conservation of angular momentum, while (b) invari- and pseudoangular momentum of quasiparticles, such as ance under rotations of fields with a fixed background implies magnons and phonons. -

Residential Square Footage Guidelines

R e s i d e n t i a l S q u a r e F o o t a g e G u i d e l i n e s North Carolina Real Estate Commission North Carolina Real Estate Commission P.O. Box 17100 • Raleigh, North Carolina 27619-7100 Phone 919/875-3700 • Web Site: www.ncrec.gov Illustrations by David Hall Associates, Inc. Copyright © 1999 by North Carolina Real Estate Commission. All rights reserved. 7,500 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $.000 per copy. • REC 3.40 11/1/2013 Introduction It is often said that the three most important factors in making a home buying decision are “location,” “location,” and “location.” Other than “location,” the single most-important factor is probably the size or “square footage” of the home. Not only is it an indicator of whether a particular home will meet a homebuyer’s space needs, but it also affords a convenient (though not always accurate) method for the buyer to estimate the value of the home and compare it to other properties. Although real estate agents are not required by the Real Estate License Law or Real Estate Commission rules to report the square footage of properties offered for sale (or rent), when they do report square footage, it is essential that the information they give prospective purchasers (or tenants) be accurate. At a minimum, information concerning square footage should include the amount of living area in the dwelling. The following guidelines and accompanying illustrations are designed to assist real estate brokers in measuring, calculating and reporting (both orally and in writing) the living area contained in detached and attached single-family residential buildings. -

A Diagrammatic Formal System for Euclidean Geometry

A DIAGRAMMATIC FORMAL SYSTEM FOR EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nathaniel Gregory Miller May 2001 c 2001 Nathaniel Gregory Miller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A DIAGRAMMATIC FORMAL SYSTEM FOR EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY Nathaniel Gregory Miller, Ph.D. Cornell University 2001 It has long been commonly assumed that geometric diagrams can only be used as aids to human intuition and cannot be used in rigorous proofs of theorems of Euclidean geometry. This work gives a formal system FG whose basic syntactic objects are geometric diagrams and which is strong enough to formalize most if not all of what is contained in the first several books of Euclid’s Elements.Thisformal system is much more natural than other formalizations of geometry have been. Most correct informal geometric proofs using diagrams can be translated fairly easily into this system, and formal proofs in this system are not significantly harder to understand than the corresponding informal proofs. It has also been adapted into a computer system called CDEG (Computerized Diagrammatic Euclidean Geometry) for giving formal geometric proofs using diagrams. The formal system FG is used here to prove meta-mathematical and complexity theoretic results about the logical structure of Euclidean geometry and the uses of diagrams in geometry. Biographical Sketch Nathaniel Miller was born on September 5, 1972 in Berkeley, California, and grew up in Guilford, CT, Evanston, IL, and Newtown, CT. After graduating from Newtown High School in 1990, he attended Princeton University and graduated cum laude in mathematics in 1994. -

A Set of Formulae on Fractal Dimension Relations and Its Application to Urban Form

A Set of Formulae on Fractal Dimension Relations and Its Application to Urban Form Yanguang Chen (Department of Geography, College of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, PRC. E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The area-perimeter scaling can be employed to evaluate the fractal dimension of urban boundaries. However, the formula in common use seems to be not correct. By means of mathematical method, a new formula of calculating the boundary dimension of cities is derived from the idea of box-counting measurement and the principle of dimensional consistency in this paper. Thus, several practical results are obtained as follows. First, I derive the hyperbolic relation between the boundary dimension and form dimension of cities. Using the relation, we can estimate the form dimension through the boundary dimension and vice versa. Second, I derive the proper scales of fractal dimension: the form dimension comes between 1.5 and 2, and the boundary dimension comes between 1 and 1.5. Third, I derive three form dimension values with special geometric meanings. The first is 4/3, the second is 3/2, and the third is 1+21/2/2≈1.7071. The fractal dimension relation formulae are applied to China’s cities and the cities of the United Kingdom, and the computations are consistent with the theoretical expectation. The formulae are useful in the fractal dimension estimation of urban form, and the findings about the fractal parameters are revealing for future city planning and the spatial optimization of cities. Key words: Allometric scaling; Area-perimeter scaling; Fractal; Structural fractal; Textural fractal; Form dimension; Boundary dimension; Urban form; Urban shape 1 1 Introduction An urban landscape in a digital map is a kind of irregular pattern consisting of countless fragments. -

Pythagoras' Theorem Information Sheet Finding the Length of the Hypotenuse

Pythagoras’ Theorem In this activity you will use Pythagoras’ Theorem to solve real-life problems. Information sheet There is a formula relating the three sides of a right-angled triangle. It can be used to mark out right angles on sports pitches and buildings. If the length of the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is c and the lengths of the other sides are a and b: 2 2 2 c = a + b c 2 2 2 a and a = c – b 2 2 2 and b = c – a b To find the hypotenuse, add the squares of the other sides, then take the square root. To find a shorter side, subtract the squares of the other sides, then take the square root. Think about … How do you decide which sides to call a, b and c? How do you decide whether to add or subtract? Finding the length of the hypotenuse: example Find c. 12.4 cm 6.3 cm c How to do it …. Using Pythagoras gives c2 = 6.32 + 12.42 c 2 = 39.69 + 153.76 = 193.45 c = 193.45 = 13.9086… c = 13.9 cm (to 1 dp) Nuffield Free-Standing Mathematics Activity ‘Pythagoras Theorem’ Student sheets Copiable page 1 of 4 © Nuffield Foundation 2012 ● downloaded from www.fsmq.org Rollercoaster example C The sketch shows part of a rollercoaster ride between two points, A and B at the same horizontal level. drop The highest point C is 20 metres above AB, ramp 30 m the length of the ramp is 55 metres, and 55 m 20 m the length of the drop is 30 metres.