111Th Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Qtnugrrss Uf Tir Unitcb Iatr% Maalpugtrnz, 3Qt Fl515

Qtnugrrss uf tIr Unitcb Iatr% maalpugtrnz, 3Qt fl515 October 14, 2020 Mike Pompeo Alex Azar II Secretary of State Secretary of Health and Human Services Department of State Department of Health and Human Services 2201 C Street NW 301 7th St. SE Washington, D.C. 20520 Washington, D.C. 20229 Dear Secretary Pompeo and Secretary Azar: We write to express our serious concern over the Trump administration’s reckless approach to U.S.—international health cooperation that reversed long-standing successful policies advocated on a bipartisan basis by previous administrations. Your actions limited American cooperation with the European Union and removed American experts from the ground in China, where the outbreak began. This impeded the ability of American public health officials to receive timely and accurate information about the pandemic, delaying our response and likely costing American lives. We urge you to immediately reestablish common-sense cooperation with the global community and to explore additional measures that could further strengthen our domestic and international capacity to control the virus and save lives. The initial response to the COVID-19 outbreak by the Chinese government was demonstrably flawed and seriously problematic. However, prior to this outbreak, your Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) dramatically downsized the U.S.’ global epidemic prevention activities. This led to both the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health reducing U.S. personnel in China as well as the closure of the National Science Foundation office there. This deprived the U.S. of early and accurate information on the novel coronavirus outbreak and impeded our ability to prepare and respond. -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

Annual Women in Leadership Issue Annual Women in Leadership

BusinessSOUTHSIDE ExchangeA DAILY JOURNAL PUBLICATION SPRING 2020 Rosie Chambers Marla Clark BLUE COLLAR JOBSCheryl OUTLOOK Dobbs Kelsey Kasting ANNUAL WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP ISSUE ANNUAL WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP ISSUE PERMIT NO. 220 NO. PERMIT GREENFIELD, IN GREENFIELD, STANDARD PRESORTED DJ-35033581 The Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana) · 3 Feb 1995, Fri · Page 2 Downloaded on Feb 13, 2020 BusinessSOUTHSIDE Exchange SPRING 2020 I VOLUME 18 I NUMBER 1 HOOSIER WOMEN FIRSTS COPYRIGHT © DAILY JOURNAL, 2020 ALL RighTS RESERVED. People on the Move SUBSCRIPTIONS 4 22 SOUTHSidE BUSINESS EXCHANGE IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY by THE DAILY JOURNAL. ThE MAGAZINE IS MAILED AT NO CHARGE TO BUSINESSES THROUghOUT GREATER JOHNSON COUNTY. 8 Corporate Chatter TO SUBSCRIBE, SEND YOUR NAME Clipped By: AND addRESS TO: DAILY JOURNAL, P.O. BOX 699, FRANKLIN, IN 46131 12 Women in Leadership AIM_EMMAeIL:d biiZ@aD_AIILYnJOURNAL.NETdiana Thu, EDFITOReb: A1M3Y MA, 2Y 736-2726020 [email protected] 22 Hoosier Women Firsts ADVERTISING: ChRIS COSNER 736-2750 [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGN: ANNA pERLICH Southside Snapshot [email protected] 26 Copyright © 2020POSTM NewASTsEpR aSepNDe addrs.RcESSo mCHA.NG AESl lTO: R ights Reserved. DAILY JOURNAL, P.O. BOX 699, FRANKLIN, IN 46131 27 Leadership Johnson County workshops SOUTHSidE BUSINESS EXCHANGE IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY AND diRECT MAILED ON THE fiNAL 28 Ribbon Cuttings DAY OF FEBRUARY (SpRING), MAY (SUMMER), ON THE COVER AUGUST (FALL) AND NOVEMBER (WINTER). Top row, from left: Rosie Cham- DEADLINES FOR EdiTORIAL CONTENT ARE THE fiRST OF THE MONTH IN whiCH THE MAGAZINE IS MAILED. bers, Marla Clark, bottom row: Cheryl Dobbs, Kelsey Kasting PHOTOS BY MARK FREELAND Southside Business Exchange | SPRING 2020 3 n Franklin College offices are located at has named Andrew 5255 E. -

Campaign Committee Transfers to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee JOHN KERRY for PRESIDENT, INC. $3,000,000 GORE 2

Campaign Committee Transfers to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee JOHN KERRY FOR PRESIDENT, INC. $3,000,000 GORE 2000 INC.GELAC $1,000,000 AL FRIENDS OF BUD CRAMER $125,000 AL COMMITTEE TO ELECT ARTUR DAVIS TO CONGRESS $10,000 AR MARION BERRY FOR CONGRESS $135,000 AR SNYDER FOR CONGRESS CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $25,500 AR MIKE ROSS FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $200,000 AS FALEOMAVAEGA FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $5,000 AZ PASTOR FOR ARIZONA $100,000 AZ A WHOLE LOT OF PEOPLE FOR GRIJALVA CONGRESSNL CMTE $15,000 CA WOOLSEY FOR CONGRESS $70,000 CA MIKE THOMPSON FOR CONGRESS $221,000 CA BOB MATSUI FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $470,000 CA NANCY PELOSI FOR CONGRESS $570,000 CA FRIENDS OF CONGRESSMAN GEORGE MILLER $310,000 CA PETE STARK RE-ELECTION COMMITTEE $100,000 CA BARBARA LEE FOR CONGRESS $40,387 CA ELLEN TAUSCHER FOR CONGRESS $72,000 CA TOM LANTOS FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $125,000 CA ANNA ESHOO FOR CONGRESS $210,000 CA MIKE HONDA FOR CONGRESS $116,000 CA LOFGREN FOR CONGRESS $145,000 CA FRIENDS OF FARR $80,000 CA DOOLEY FOR THE VALLEY $40,000 CA FRIENDS OF DENNIS CARDOZA $85,000 CA FRIENDS OF LOIS CAPPS $100,000 CA CITIZENS FOR WATERS $35,000 CA CONGRESSMAN WAXMAN CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $200,000 CA SHERMAN FOR CONGRESS $115,000 CA BERMAN FOR CONGRESS $215,000 CA ADAM SCHIFF FOR CONGRESS $90,000 CA SCHIFF FOR CONGRESS $50,000 CA FRIENDS OF JANE HARMAN $150,000 CA BECERRA FOR CONGRESS $125,000 CA SOLIS FOR CONGRESS $110,000 CA DIANE E WATSON FOR CONGRESS $40,500 CA LUCILLE ROYBAL-ALLARD FOR CONGRESS $225,000 CA NAPOLITANO FOR CONGRESS $70,000 CA PEOPLE FOR JUANITA MCDONALD FOR CONGRESS, THE $62,000 CA COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LINDA SANCHEZ $10,000 CA FRIENDS OF JOE BACA $62,000 CA COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LORETTA SANCHEZ $150,000 CA SUSAN DAVIS FOR CONGRESS $100,000 CO SCHROEDER FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE, INC $1,000 CO DIANA DEGETTE FOR CONGRESS $125,000 CO MARK UDALL FOR CONGRESS INC. -

Sponsorship Opportunities Sponsorship Opportunities We Are Global Leaders

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES WE ARE GLOBAL LEADERS CBCF Vision: We envision a world in which all communities have an equal voice in public policy through leadership cultivation, economic empowerment, and civic engagement. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 2 CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS NATIONAL LEADERSHIP CBC MEMBERS IN LEADERSHIP HOUSE EXECUTIVE LEADERSHIP 116TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE CHAIRS 4 Rep. James E. Clyburn Rep. Maxine Waters Majority Whip House Financial Services Committee Rep. Karen Bass Rep. Cedric L. Chair, CBC Richmond Rep. Bobby Scott CBCF Chair, Board of Education and the Workforce Directors Committee Rep. Hakeem Jeffries Democratic Caucus Chairman SENATORS IN THE CBC Rep. Bennie Thompson Homeland Security Rep. Barbara Lee Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson Co-chair, Steering and Policy Science, Space and Technology Committee Sen. Cory Booker Sen. Kamala D. Harris HOUSE SUBCOMMITTEE CHAIRS 28 SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 3 CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS NATIONAL REACH Representing more than 82 MILLION Americans in 26 States & 1 Territory 41% of the total U.S. African American population 25% of the total CBC Member U.S. population States/Territory 54 49 MEMBERS YEARS OF EMPOWERMENT SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 4 WE ARE CHANGING THE WORLD CBCF Mission: The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Inc. works to advance the global black community by developing leaders, informing policy, and educating the public. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 5 LUXURIOUS LOCATION This year’s Scholarship Classic will be hosted at the luxurious Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay Golf Resort, Spa and Marina in Cambridge, Maryland. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 6 IDEAS & DEVELOPING INFORMATION LEADERS Facilitating the exchange Providing leadership OUR WORK of ideas and information development and to address critical issues scholarship opportunities to TO ACHIEVE affecting our community. -

Presidential Appointments Primer

2021 NALEO Presidential Appointments Primer 2021 NALEO | PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTMENTS PRIMER America’s Latinos are strongly committed to public service at all levels of government, and possess a wealth of knowledge and skills to contribute as elected and appointed officials. The number of Latinos in our nation’s civic leadership has been steadily increasing as Latinos successfully pursue top positions in the public and private sectors. Throughout their tenure, and particularly during times of transition following elections, Presidential administrations seek to fill thousands of public service leadership and high-level support positions, and governing spots on advisory boards, commissions, and other bodies within the federal government. A strong Latino presence in the highest level appointments of President Joe Biden’s Administration is crucial to help ensure that the Administration develops policies and priorities that effectively address the issues facing the Latino community and all Americans. The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) Educational Fund is committed to ensuring that the Biden Administration appoints qualified Latinos to top government positions, including those in the Executive Office of the President, Cabinet-level agencies, sub-Cabinet, and the federal judiciary. This Primer provides information about the top positions available in the Biden Administration and how to secure them through the appointments process. 2021 NALEO | PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTMENTS PRIMER 2 2021 NALEO Presidential Appointments Primer TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND 4 AVAILABLE POSITIONS AND COMPENSATION 5 HOW TO APPLY 8 TYPICAL STEPS 10 In the Presidential Appointments Process NECESSARY CREDENTIALS 11 IS IT WORTH IT? 12 Challenges and Opportunities Of Presidential Appointments ADVOCACY & TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE 13 For Latino Candidates & Nominees 2021 NALEO | PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTMENTS PRIMER 3 BACKGROUND During the 1970’s and 1980’s, there were very few Latinos considered for appointments in the federal government. -

Lobbying Contribution Report

8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report LOBBYING CONTRIBUTION REPORT Clerk of the House of Representatives • Legislative Resource Center • 135 Cannon Building • Washington, DC 20515 Secretary of the Senate • Office of Public Records • 232 Hart Building • Washington, DC 20510 1. FILER TYPE AND NAME 2. IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS Type: House Registrant ID: Organization Lobbyist 35195 Organization Name: Senate Registrant ID: Honeywell International 57453 3. REPORTING PERIOD 4. CONTACT INFORMATION Year: Contact Name: 2016 Ms.Stacey Bernards MidYear (January 1 June 30) Email: YearEnd (July 1 December 31) [email protected] Amendment Phone: 2026622629 Address: 101 CONSTITUTION AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001 USA 5. POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE NAMES Honeywell International Political Action Committee 6. CONTRIBUTIONS No Contributions #1. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Friends of Sam Johnson Sam Johnson #2. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,500.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Kay Granger Campaign Fund Kay Granger #3. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $2,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: Paul Cook for Congress Paul Cook https://lda.congress.gov/LC/protected/LCWork/2016/MM/57453DOM.xml?1470093694684 1/75 8/1/2016 LD203 Contribution Report #4. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: DelBene for Congress Suzan DelBene #5. Contribution Type: Contributor Name: Amount: Date: FECA Honeywell International Political Action Committee $1,000.00 01/14/2016 Payee: Honoree: John Carter for Congress John Carter #6. -

2017 Political Contributions (January 1 – June 30)

2017 Political Contributions (January 1 – June 30) Amgen is committed to serving patients by transforming the promise of science and biotechnology into therapies that have the power to restore health or even save lives. Amgen recognizes the importance of sound public policy in achieving this goal, and, accordingly, participates in the political process and supports those candidates, committees, and other organizations who work to advance healthcare innovation and improve patient access. Amgen participates in the political process by making direct corporate contributions as well as contributions through its employee-funded Political Action Committee (“Amgen PAC”). In some states, corporate contributions to candidates for state or local elected offices are permissible, while in other states and at the federal level, political contributions are only made through the Amgen PAC. Under certain circumstances, Amgen may lawfully contribute to other political committees and political organizations, including political party committees, industry PACs, leadership PACs, and Section 527 organizations. Amgen also participates in ballot initiatives and referenda at the state and local level. Amgen is committed to complying with all applicable laws, rules, and regulations that govern such contributions. The list below contains information about political contributions for the first half of 2017 by Amgen and the Amgen PAC. It includes contributions to candidate committees, political party committees, industry PACs, leadership PACs, Section 527 organizations, and state and local ballot initiatives and referenda. These contributions are categorized by state, political party (if applicable), political office (where applicable), recipient, contributor (Amgen Inc. or Amgen PAC) and amount. Office Candidate State Party Office Committee/PAC Name Candidate Name Corp. -

August 10, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Steny

August 10, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Steny Hoyer Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer, As we advance legislation to rebuild and renew America’s infrastructure, we encourage you to continue your commitment to combating the climate crisis by including critical clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives in the upcoming infrastructure package. These incentives will play a critical role in America’s economic recovery, alleviate some of the pollution impacts that have been borne by disadvantaged communities, and help the country build back better and cleaner. The clean energy sector was projected to add 175,000 jobs in 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic upended the industry and roughly 300,000 clean energy workers were still out of work in the beginning of 2021.1 Clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives are an important part of bringing these workers back. It is critical that these policies support strong labor standards and domestic manufacturing. The importance of clean energy tax policy is made even more apparent and urgent with record- high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, unprecedented drought across the West, and the impacts of tropical storms felt up and down the East Coast. We ask that the infrastructure package prioritize inclusion of a stable, predictable, and long-term tax platform that: Provides long-term extensions and expansions to the Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035; Extends and modernizes tax incentives for commercial and residential energy efficiency improvements and residential electrification; Extends and modifies incentives for clean transportation options and alternative fuel infrastructure; and Supports domestic clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation manufacturing. -

2018 BMS PAC Contributions

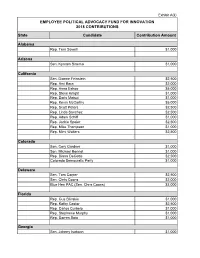

Exhibit A(ii) EMPLOYEE POLITICAL ADVOCACY FUND FOR INNOVATION 2018 CONTRIBUTIONS State Candidate Contribution Amount Alabama Rep. Terri Sewell $1,000 Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema $1,000 California Sen. Dianne Feinstein $2,500 Rep. Ami Bera $2,000 Rep. Anna Eshoo $5,000 Rep. Steve Knight $1,000 Rep. Doris Matsui $1,000 Rep. Kevin McCarthy $5,000 Rep. Scott Peters $2,500 Rep. Linda Sanchez $2,500 Rep. Adam Schiff $1,000 Rep. Jackie Speier $2,500 Rep. Mike Thompson $1,000 Rep. Mimi Walters $2,500 Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner $1,000 Sen. Michael Bennet $1,000 Rep. Diana DeGette $2,500 Colorado Democratic Party $1,000 Delaware Sen. Tom Carper $2,500 Sen. Chris Coons $2,000 Blue Hen PAC (Sen. Chris Coons) $3,000 Florida Rep. Gus Bilirakis $1,000 Rep. Kathy Castor $2,500 Rep. Carlos Curbelo $1,000 Rep. Stephanie Murphy $1,000 Rep. Darren Soto $1,000 Georgia Sen. Johnny Isakson $1,000 Sen. David Perdue $2,000 Rep. Buddy Carter $2,500 Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds $2,000 Sen. Chuck Grassley $2,500 State Sen. Charles Schneider $2,000 State Sen. Tom Shipley $500 Idaho Sen. Mike Crapo $5,000 Illinois Rep. Cheri Bustos $1,000 Rep. Bill Foster $1,000 Rep. Robin Kelly $1,000 Rep. Darin LaHood $1,000 Rep. Pete Roskam $1,000 Rep. Brad Schneider $1,000 Rep. John Shimkus $2,500 Indiana Sen. Mike Braun $1,000 Sen. Joe Donnelly $2,500 Rep. Larry Bucshon $2,500 Rep. Susan Brooks $2,000 Rep. Andre Carson $1,000 Rep. -

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby (R) Presbyterian Representatives Robert B. Aderholt (R) Congregationalist Baptist Spencer Bachus (R) Baptist Jo Bonner (R) Episcopalian Bobby N. Bright (D) Baptist Artur Davis (D) Lutheran Parker Griffith (D) Episcopalian Mike D. Rogers (R) Baptist ALASKA Senators Mark Begich (D) Roman Catholic Lisa Murkowski (R) Roman Catholic Representatives Don Young (R) Episcopalian ARIZONA Senators Jon Kyl (R) Presbyterian John McCain (R) Baptist Representatives Jeff Flake (R) Mormon Trent Franks (R) Baptist Gabrielle Giffords (D) Jewish Raul M. Grijalva (D) Roman Catholic Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Roman Catholic Harry E. Mitchell (D) Roman Catholic Ed Pastor (D) Roman Catholic John Shadegg (R) Episcopalian ARKANSAS Senators Blanche Lincoln (D) Episcopalian Mark Pryor (D) Christian Representatives Marion Berry (D) Methodist John Boozman (R) Baptist Mike Ross (D) Methodist Vic Snyder (D) Methodist CALIFORNIA Senators Barbara Boxer (D) Jewish Dianne Feinstein (D) Jewish Representatives Joe Baca (D) Roman Catholic Xavier Becerra (D) Roman Catholic Howard L. Berman (D) Jewish Brian P. Bilbray (R) Roman Catholic Ken Calvert (R) Protestant John Campbell (R) Presbyterian Lois Capps (D) Lutheran Dennis Cardoza (D) Roman Catholic Jim Costa (D) Roman Catholic Susan A. Davis (D) Jewish David Dreier (R) Christian Scientist Anna G. Eshoo (D) Roman Catholic Sam Farr (D) Episcopalian Bob Filner (D) Jewish Elton Gallegly (R) Protestant Jane Harman (D) Jewish Wally Herger (R) Mormon Michael M. Honda (D) Protestant Duncan Hunter (R) Protestant Darrell Issa (R) Antioch Orthodox Christian Church Barbara Lee (D) Baptist Jerry Lewis (R) Presbyterian Zoe Lofgren (D) Lutheran Dan Lungren (R) Roman Catholic Mary Bono Mack (R) Protestant Doris Matsui (D) Methodist Kevin McCarthy (R) Baptist Tom McClintock (R) Baptist Howard P.