The Government Monitoring and Evaluation System in India: a Work in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Systems and Accommodation of Distinct Groups: a Comparative Survey of Institutional Arrangements for Aboriginal Peoples

1 arrangements within other federations will focus FEDERAL SYSTEMS AND on provisions for constitutional recognition of ACCOMMODATION OF DISTINCT Aboriginal Peoples, arrangements for Aboriginal GROUPS: A COMPARATIVE SURVEY self-government (including whether these take OF INSTITUTIONAL the form of a constitutional order of government ARRANGEMENTS FOR ABORIGINAL or embody other institutionalized arrangements), the responsibilities assigned to federal and state PEOPLES1 or provincial governments for Aboriginal peoples, and special arrangements for Ronald L. Watts representation of Aboriginal peoples in federal Institute of Intergovernmental Relations and state or provincial institutions if any. Queen's University Kingston, Ontario The paper is therefore divided into five parts: (1) the introduction setting out the scope of the paper, the value of comparative analysis, and the 1. INTRODUCTION basic concepts that will be used; (2) an examination of the utility of the federal concept (1) Purpose, relevance and scope of this for accommodating distinct groups and hence the study particular interests and concerns of Aboriginal peoples; (3) the range of variations among federal The objective of this study is to survey the systems which may facilitate the accommodation applicability of federal theory and practice for of distinct groups and hence Aboriginal peoples; accommodating the interests and concerns of (4) an overview of the actual arrangements for distinct groups within a political system, and Aboriginal populations existing in federations -

Democracy in the United States

Democracy in the United States The United States is a representative democracy. This means that our government is elected by citizens. Here, citizens vote for their government officials. These officials represent the citizens’ ideas and concerns in government. Voting is one way to participate in our democracy. Citizens can also contact their officials when they want to support or change a law. Voting in an election and contacting our elected officials are two ways that Americans can participate in their democracy. Voting booth in Atascadero, California, in 2008. Photo by Ace Armstrong. Courtesy of the Polling Place Photo Project. Your Government and You H www.uscis.gov/citizenship 1 Becoming a U.S. Citizen Taking the Oath of Allegiance at a naturalization ceremony in Washington, D.C. Courtesy of USCIS. The process required to become a citizen is called naturalization. To become a U.S. citizen, you must meet legal requirements. You must complete an interview with a USCIS officer. You must also pass an English and Civics test. Then, you take the Oath of Allegiance. This means that you promise loyalty to the United States. When you become a U.S. citizen, you also make these promises: ★ give up loyalty to other countries ★ defend the Constitution and laws of the United States ★ obey the laws of the United States ★ serve in the U.S. military (if needed) ★ do important work for the nation (if needed) After you take the Oath of Allegiance, you are a U.S. citizen. 2 Your Government and You H www.uscis.gov/citizenship Rights and Responsibilities of Citizens Voting is one important right and responsibility of U.S. -

64Th ANNUAL REPORT

64th (2013-14) Annual Report UNION PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Dholpur House, Shahjahan Road New Delhi – 110069 http: //www.upsc.gov.in The Union Public Service Commission have the privilege to present before the President their Sixty Fourth Report as required under Article 323(1) of the Constitution. This Report covers the period from April 1, 2013 (Chaitra 11, 1935 Saka) to March 31, 2014 (Chaitra 10, 1936 Saka). Annual Report 2013-14 Contents List of abbreviations ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- (ix) Composition of the Commission during the year 2013-14 ----------------------------- (xi) List of Chapters Chapter Heading Page No. 1 Highlights 1-3 2 Brief History and Workload over the years 5-10 3 Recruitment by Examinations 11-19 4 Direct Recruitment by Selection 21-27 5 Recruitment Rules, Service Rules and Mode of Recruitment 29-31 6 Promotions and Deputations 33-40 7 Representation of candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled 41-44 Tribes, Other Backward Classes and Persons with Disabilities 8 Disciplinary Cases 45-46 9 Delays in implementing advice of the Commission 47-48 10 Non-acceptance of the Advice of the Commission by the Government 49-70 11 Administration and Finance 71-72 12 Miscellaneous 73-77 Acknowledgement 79 List of Appendices Appendix Subject Page No. 1 Profiles of Hon’ble Chairman and Hon’ble Members of the Commission. 81-88 2 Recommendations made by the Commission – Relating to suitability of 89 candidates/officials. 3 Recommendations made by the Commission – Relating to Exemption 89 cases, Service matters, Seniority etc. 4 Recruitment by Examinations – Details of recommendations made during 90 the year 2013-14 for Civil Services/Posts. -

State Revival the Role of the States in Australia’S COVID-19 Response and Beyond

State revival The role of the states in Australia’s COVID-19 response and beyond Australia’s states and territories have taken the lead in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, supported by constitutional powers and popular mandates. With the states newly emboldened, further action on climate change, changes to federal–state financial arrangements and reform of National Cabinet could all be on the agenda. Discussion paper Bill Browne July 2021 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. -

Tools and Techniques of Effective Governors

MANAGEMENT BRIEF: TRANSITION INTO OFFICE Tools and Techniques of Effective Governors Introduction independent authority around critical issues such as budgeting, personnel and procurement. A governor’s Over the past several years, National Governors authority in these areas will be more limited. Association (NGA) Consulting has conducted considerable research and produced resources for the A business CEO will usually exercise more control organization and operation of the governor’s office. over his or her board of directors than a governor can Recently, NGA Consulting has focused its attention exercise over an independent legislature. A legislator, on the governor’s role in leadership and management an academic or an advocate can focus on broad policy of state government. As this work progressed, it issues with little immediate concern for the became clear that those who seek to be governor or mechanics of implementation. A governor must see who play important roles in the governor’s office that his or her policies not only are adopted but should understand the tools available to help implemented in an effective and efficient manner. governors effectively lead and manage state Individuals outside the executive branch can point government. fingers and raise questions because their role is often to hold others accountable. In most cases, it is the This management brief provides an overview of the governor who will be accountable in the public’s eye primary tools available to governors: and who must realize that indeed “the buck stops here.” • Accessing information; • Setting priorities; Many officials in business and politics struggle for • Managing the governor’s staff; media attention, but governors are constantly in the • Selecting key personnel; public eye. -

Order T-1/2021 Current Placeof Posting Commissioner, O/O DC-Msmeaffairs

F.No.13016/1/2020-1ES Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Economic Affairs (IES Cadre) Room No 59, North Block New Delhi, Dated: 15.2.2021. Order T-1/2021 Subject: Transfer/Posting of officers of the Indian Economic Service. The following officers of the Indian Economic Service are hereby transferred and posted with immediate effect and until further orders as under S.No. Name of the Officer and Posted as/to Remarks current placeof posting 1. Shri Santanu Mitra (IES:1993), Economic Adviser, |Against a vacant Additional Development Ministry of External | post Commissioner, O/o DC-MSMEAffairs 2. | Dr Ishita Ganguli Tripathy | Additional Development Vice Shri Santanu (IES:1999), Director, Department Commissioner, Olo DC, | Mitra (1ES:1993) of Commerce (on return from Ministry of Micro, Small transferred deputation and Medium Enterprises 3 Dr.C. Vanlalramsanga Economic Adviser, Vice Shri Ajay (IES:2001), Secretary, Department of Srivastava Planning and Programme Commerce (IES:1996) who Implementation, Government of has proceeded on Mizoram (on return from deputation deputation) 2. The charge handing over/taking over report of the officers may be sent to this Department (1ES Cadre) for record. 3. This issues with the approval of the Competent Authority. (Gaurav Kumar Jha) Deputy Director IES Cadre To, 1. Secretary, Department of Commerce, Udyog Bhawan, New Delhi. 2 Chief Secretary, Government of Mizoram, New Secretariat Complex, Aizwal- 796001 3. Additional Secretary & Development Commissioner, O/o DC, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, HQ, office of DC-MSME "A" Wing 7th Floor, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi. 4. Joint Secretary (Administration), Ministry of External Affairs, South Block, New Delhi 5. -

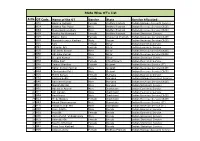

State Wise OT's List

State Wise OT's List S.No OT Code Name of the OT Gender State Service Allocated 1 A31 Harisha Vellanki Female Andhra Pradesh Indian Railway Accounts Service 2 A14 Krishna Rao Pujari Male Andhra Pradesh Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 3 A44 Maga Sandeep Bura Male Andhra Pradesh Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 4 A09 Anitha Panthampalli Female Andhra Pradesh Indian Statistical Service 5 A04 Mamu Bullo Female Arunachal Pradesh Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 6 A10 Manashkhungur Kachari Male Assam Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 7 B01 Kirti Female Bihar Indian Economic Service 8 B42 Shamim Ara Female Bihar Indian Economic Service 9 A35 Abhishek Kumar Male Bihar Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 10 B56 Abhinaw Kumar Male Bihar Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 11 A51 Deepak Kumar Male Bihar Indian Statistical Service 12 B32 Nitika Pant Female Chhattisgarh Indian Economic Service 13 A02 Swapnil Parihar Female Gujarat Indian Revenue Service (IT) 14 A39 Rahul Kumar Parmar Male Gujarat Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 15 B04 Chintanbhai Patel Male Gujarat Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 16 B35 Preeti Balyan Female Haryana Indian Economic Service 17 B53 Garima Sodhi Female Haryana Indian Railway Personnel Service 18 B40 Ravinder Kumar Male Haryana Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 19 B24 Manish Bindal Male Haryana Indian Statistical Service 20 A01 Abhishek Anand Male Jharkhand Indian Economic Service 21 A11 Ajit Ranjan Male Jharkhand Indian Economic Service 22 A54 Amit Renu Male Jharkhand Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) 23 B22 Pinky Baskey Female Jharkhand Indian Revenue Service(C&CE) -

Unicameralism and the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 Val Nolan, Jr.*

DOCUMENT UNICAMERALISM AND THE INDIANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1850 VAL NOLAN, JR.* Bicameralism as a principle of legislative structure was given "casual, un- questioning acceptance" in the state constitutions adopted in the nineteenth century, states Willard Hurst in his recent study of main trends in the insti- tutional development of American law.1 Occasioning only mild and sporadic interest in the states in the post-Revolutionary period,2 problems of legislative * A.B. 1941, Indiana University; J.D. 1949; Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Uni- versity School of Law. 1. HURST, THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN LAW, THE LAW MAKERS 88 (1950). "O 1ur two-chambered legislatures . were adopted mainly by default." Id. at 140. During this same period and by 1840 many city councils, unicameral in colonial days, became bicameral, the result of easy analogy to state governmental forms. The trend was reversed, and since 1900 most cities have come to use one chamber. MACDONALD, AmER- ICAN CITY GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 49, 58, 169 (4th ed. 1946); MUNRO, MUNICIPAL GOVERN-MENT AND ADMINISTRATION C. XVIII (1930). 2. "[T]he [American] political theory of a second chamber was first formulated in the constitutional convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 and more systematically developed later in the Federalist." Carroll, The Background of Unicameralisnl and Bicameralism, in UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURES, THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL DEBATE HAND- BOOK, 1937-38, 42 (Aly ed. 1938). The legislature of the confederation was unicameral. ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, V. Early American proponents of a bicameral legislature founded their arguments on theoretical grounds. Some, like John Adams, advocated a second state legislative house to represent property and wealth. -

Sharon M. Barnhardt

SHARON M. BARNHARDT FLAME University, Raman 107 mobile: +91 99620 72412 Lavale, Pune 412115 [email protected] POSITIONS 2016 − present Director and Primary Investigator for Economics & Public Policy, CESS Nuffield — FLAME University (Pune) 2013 − 2016 Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad) 2010 − 2013 Assistant Professor, Institute for Financial Management and Research (Chennai) PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Affiliated Professor, MIT Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) Research Fellow, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) RESEARCH INTERESTS Microeconomics of development, urban development, health economics, labor economics, social economics, governance and policing EDUCATION 2010 Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Ph.D. Public Policy Dissertation Title: Essays on the Impact of Residential Location on Networks, Attitudes and Cooperation: Experimental Evidence from India Committee: Erica Field, Larry Katz, Rohini Pande 2003 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ M.P.A., International Development 1996 New York University, New York, NY B.S., Finance and International Business, Magna Cum Laude PUBLICATIONS Banerjee, A., Barnhardt, S., & Duflo, E. (forthcoming). Can Iron-Fortified Salt Control Anemia? Evidence from Two Experiments in Rural Bihar. Journal of Development Economics. Barnhardt, S., Field, E. and Pande, R. (2017) “Moving to Opportunity or Isolation? Network Effects of a Randomized Housing Lottery in Urban India” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. Banerjee, A., Barnhardt, S., & Duflo, E. (2017). “Movies, Margins, and Marketing: Encouraging the Adoption of Iron-Fortified Salt” in Insights in the Economics of Aging, David A. Wise, editor. University of Chicago Press. Banerjee, A., S. Barnhardt, and E. Duflo. (2014) “Nutrition, Iron Deficiency Anemia and the Demand for Iron Fortified Salt: Evidence from an Experiment in Rural Bihar” in Discoveries in the Economics of Aging, David A. -

Article 14 of the Constitution of India Reads As Under

1 ANNEXURE II 1. EQUALITY RIGHTS (ARTICLES 14 – 18) 1.1 Article 14 of the Constitution of India reads as under: “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.” 1.2 The said Article is clearly in two parts – while it commands the State not to deny to any person ‘equality before law’, it also commands the State not to deny the ‘equal protection of the laws’. Equality before law prohibits discrimination. It is a negative concept. The concept of ‘equal protection of the laws’ requires the State to give special treatment to persons in different situations in order to establish equality amongst all. It is positive in character. Therefore, the necessary corollary to this would be that equals would be treated equally, whilst un-equals would have to be treated unequally Article 15 secures the citizens from every sort of discrimination by the State, on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth or any of them. However, this Article does not prevent the State from making any special provisions for women or children. Further, it also allows the State to extend special provisions for socially and economically backward classes for their advancement. It applies to the Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) as well. Article 16 assures equality of opportunity in matters of public employment and prevents the State from any sort of discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them. -

Organizational Structure of the Government at the Centre and State

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE GOVERNMENT AT THE CENTRE AND STATE Prof. I Ramabrahmam Dept. of Political Science University of Hyderabad Hyderabad Structure of the Indian Constitution o Article 1 (1) of the Constitution: India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States. o There are o 28 States; and o 7 Union Territories. o Neither ‘Federal’ in the classical sense nor ‘Unitary’ in character. o Some call it ‘quasi federal’ India’s Federal Structure till 1990s Federal Structure in India After 1992 Central Government State Government Local Government o Urban Local o Rural local Self- Governing Institutions Bodies o District Panchayats (540) o Corporations o Intermediate Panchayats (6096) o Municipalities o Town Areas o Village Panchayats (2,32,000) The Administrative Structure of the Government of India (The roles of the various Ministries are defined as per the Rules of Business) President Vice- President Prime Minister Council of Ministers Minister Minister Minister Secretary Additional Secretary Joint Secretary Continued… o Articles 52 to 62 of Indian Constitution explains the President of India and his election procedure, executive powers etc o Article 63 to 71 deals with the vice-president of India and his election procedure, functions, terms of office, Qualification etc. o Article 73 to 78 of Indian Constitution deals with duties and functions of the Prime Minister and the council of ministers The Administrative Structure of the State Governments Governor Chief Minister Council of Ministers Minister Minister Minister Secretary Additional Secretary Joint Secretary Continued… o Article 152 of Indian Constitution speaks about the State Governments except the Jammu & Kashmir o Article 153 to 161 deals with the Governors of States and their functions, election, eligibility, and duties etc o 163, 164, and 167 articles of the Indian Constitution deals with the Chief Minister and council of Ministers. -

10. the All India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1968

10. 1THE ALL INDIA SERVICES (CONDUCT) RULES, 1968 In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the All India Services Act, 1951 (61 of 1951), the Central Government after consultation with the Governments of the State concerned, hereby makes the following rules, namely:— 1. Short title and commencement. — 1(1) These rules may be called the All India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1968. 1(2) They shall come into force on the date of their publication in the Official Gazette. 2. Definitions—In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires— 2.(a) “Government” means— (i) in the case of a member of the Service serving in connection with the affairs of the Union, the Central Government; or (ii) in the case of a member of the Service serving under a Foreign Government or outside India (whether on duty or on leave), the Central Government; or (iii) in the case of a member of the Service serving in connection with the affairs of a State, the Government of that State; Explanation—A member of the Service whose services are placed at the disposal of a company, corporation or other organisation or a local authority by the Central Government or the Government or the Government of a State shall for the purpose of these rules, be deemed to be a member of the Service serving in connection with the affairs of the Union or in connection with the affairs of that State, as the case may be, notwithstanding that his salary is drawn from the sources other than the Consolidated Fund of India or the Consolidated Fund of that State; 2.(b)