060417 Seanad Special Committee on the Withdrawl of the UK From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 260 Wednesday, No. 4 26 September 2018 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 26/09/2018A00100Business of Seanad 205 26/09/2018A00250Commencement Matters 206 26/09/2018A00300Water and Sewerage Schemes Funding ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������206 26/09/2018C00100Schools Building Projects Status 210 26/09/2018D01200School Transport Provision 212 26/09/2018E00300Message from Dáil 215 26/09/2018G00100Order of Business 215 26/09/2018P00100Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions Bill 2018: Second Stage ������������������������������������������231 Judicial Appointments Commission Bill 2017: Committee Stage (Resumed) 243 26/09/2018OO00400Message from Joint Committee 265 Inclusion in Sport: Motion 265 SEANAD ÉIREANN Dé Céadaoin, 26 Meán Fómhair 2018 Wednesday, 26 September 2018 Chuaigh an Leas-Chathaoirleach i gceannas ar 1030 am Machnamh agus Paidir. Reflection and Prayer. -

Seanad Éireann

[Additional list of recommendations.] SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE AIRGEADAIS (UIMH. 2) 2008 —AN COISTE FINANCE (NO. 2) BILL 2008 —COMMITTEE STAGE Moltaí Breise Additional Recommendations SECTION 2 2a. In page 13, between lines 10 and 11, to insert the following: “(d) in the case of persons whose income only exceeds the threshold set out in paragraphs (a) and (c) by €10,000, only half of the levy calculated under Part 18A will be payable.”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. SECTION 8 2b. In page 38, line 18, after “year” to insert the following: “except in the case of persons aged 70 years or over, when it means the highest rate at which they paid tax”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. 2c. In page 38, after line 45, to insert the following subsection: “(2) The Minister shall ask the Commission on Taxation to produce a report within 3 months on the impact of this Act on dental costs for families with children under 16 years of age.”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. SECTION 13 2d. In page 47, between lines 20 and 21, to insert the following: “(c) are derived from innovative activities meaning the development of a new technological, telecommunication, scientific or business process,”. -

TD,MEP, COCO Contacts.Xlsx

TD,MEP & CoCo Contact Details for MEP's, TD's and Councillors TD/MEP/CLLR Mr/Ms Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address4 Phone no Mobile Email Mayo Co Cllr Mr Al Mc Donnell Moorehall Ballyglass Claremorris Co. Mayo 094-9029039 086-8109499 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Austin Francis O'Malley Doughmackeon Roonagh P.O. Louisbourgh Co. Mayo 098-66418 087-2919477 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Blackie K Gavin Sion Hill Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9022171 087-2490933 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Brendan Mulroy 4 St.Patricks Tce. Westport Co. Mayo 087-2824702 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Christy Hyland Distillery Court Westport Co Mayo 086-8342208 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Cyril Burke Premier Estate Maloney, I.P.I. Centre Breafy Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-6891821 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Damien Ryan Neale Road Ballinrobe Co. Mayo 094-9541444 [email protected] Co.Mayo TD Mr Dara Calleary TD Pearse Street Ballina Co Mayo 096-77613 [email protected] An Taoiseach Mr Enda Kenny TD Tucker Street Castlebar Co Mayo 094-9025600 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Eugene Mc Cormack 49 Knockaphunta Park Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9023758 086-8101426 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Frank Durcan Westport Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-2589091 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Gerry Coyle Doolough Geesala Ballina Co. Mayo 097-82280 087-2441380 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Henry kenny Straide Road Ballyvary Co. -

Sponsorship Opportunity: I Am Ireland Film For

the Irish Fellowship Club of Chicago presents A concert being presented at Old Saint Pat’s in Chicago for broadcast on PBS “There will be all manner of celebrations during next year’s centennial but it’s hard – almost impossible – to imagine any will be as moving, entertaining, enlightening or soaring as I AM IRELAND.” – rick kogan, the chicago tribune I AM IRELAND The History of Ireland’s Road to Freedom 1798 ~ 1916 “As told through songs of her people” TELLING THE STORY OF IRISH INDEPENDENCE AND CREATING A LEGACY THAT WILL LIVE FOR GENERATIONS TO COME he goal of the I AM IRELAND show is to record the story of Ireland’s road to freedom filmed before a live audience at Old St. TPatrick’s Church in Chicago over a three-day period in the Fall of 2019, for distribution through the PBS Television Network. We are seek- ing to raise $500,000 to cover the cost of this production while simulta- neously raising scholarship funds for the Irish Fellowship Educational and Cultural Foundation. This filming and recording will be carried out by the acclaimed HMS Media Group, who recently filmed for broadcast the highly rated Chicago Voices Concert, (2017) featuring Renée Fleming and more recently, Jesus Christ Superstar for PBS. The I AM IRELAND show will feature traditional Irish Tenor Paddy Homan, together with 35 musicians from The City Lights Orchestra, under the direction of Rich Daniels. Additionally, there will be three traditional Irish musicians, along with an All-Ireland traditional Irish step dancer. The ninety-minute show takes audiences on a journey through the songs and speeches of Ireland’s road to freedom between 1798 and 1916. -

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 230 Wednesday, No. 8 12 March 2014 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 12/03/2014A00100Business of Seanad 2 12/03/2014A00400Order of Business 368 12/03/2014K00050Straitéis 20 Bliain don Ghaeilge: Statements 385 12/03/2014R00100Energy Policy: Motion 398 12/03/2014EE00800Adjournment Matters 432 12/03/2014EE00850Building Regulations Amendments 432 12/03/2014FF00250Small and Medium Enterprises Supports 434 SEANAD ÉIREANN Dé Céadaoin, 12 Márta 2014 Wednesday, 12 March 2014 Chuaigh an Cathaoirleach i gceannas ar 1030 am Machnamh agus Paidir. Reflection and Prayer. 12/03/2014A00100Business of Seanad 12/03/2014A00200An Cathaoirleach: I have received notice from Senator Kathryn Reilly that, on the motion for the Adjournment of the House today, she proposes to raise the following matter: The need for the Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government to discuss the Building Control (Amendment) Regulations 2014 and if amendments will be made to include architectural technologists in the regulations I have also received notice from Senator Tom Sheahan of the following matter: The need for the Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine to provide grant aid for replanting of forestry damaged by the recent storms I have also received notice from Senator Lorraine -

Annual Report 2012

TITHE AN OIREACHTAIS AN COMHCHOISTE UM GHNÓTHAÍ AN AONTAIS EORPAIGH TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL 2012 _______________ HOUSES OF THE OIREACHTAS JOINT COMMITTEE ON EUROPEAN UNION AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT 2012 31ENUA0009 Table of Contents Chairman‘s Foreword 1. Content and Format of Report 2. Establishment and Functions 2.1 Establishment and Functions of Select Committee 2.2 Establishment of Joint Committee 2.3 Functions of Joint Committee 2.4 Establishment of Joint sub-Committee 3. Chairman, Vice-Chairman, and Membership 4. Meetings, Attendance and Recording 5. Number and Duration of Meetings 5.1 Joint Committee 5.2 Dáil Select Committee 5.3 Joint sub-Committee on the Referendum on the Intergovernmental Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union 6. Witnesses attending before the Committee(s) 7. Committee Reports Published 8. Travel 9. Annual report on the Operation of the European Union (Scrutiny) Act 2002 10. Report on Functions and Powers APPENDIX 1 Orders of Reference APPENDIX 2: Membership List of Members (Joint Committee) List of Members (Joint sub-Committee on the Referendum on the Intergovernmental Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union) APPENDIX 3: Meetings of the Joint Committee APPENDIX 4: Minutes of Proceedings of the Joint Committee APPENDIX 5: Meetings of the Dáil Select Committee APPENDIX 6: Meetings of the Joint sub-Committee on the Referendum on the Intergovernmental Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union APPENDIX 7: Minutes of Proceedings of the Joint sub-Committee on the Referendum on the Intergovernmental Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union Joint Committee on European Affairs Chairman’s Foreword On behalf of the Joint Committee on European Union Affairs I am pleased to present the Annual Report on the work of the Joint Committee for the period January to December 2012. -

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 250 Wednesday, No. 6 23 February 2017 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 23/02/2017A00100Business of Seanad 371 23/02/2017A00225Commencement Matters 372 23/02/2017A00250Schools Building Projects �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������372 23/02/2017B00400Road Projects 373 23/02/2017C00400General Register Office 375 23/02/2017D00400Cancer Services Provision 377 23/02/2017G00100Order of Business 380 23/02/2017L01700Intoxicating Liquor (Amendment) Bill 2017: First Stage ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������390 23/02/2017M00100Establishment of Special Committee on Withdrawal of United Kingdom from European Union: Motion 390 23/02/2017M00500Business of Seanad 392 23/02/2017W00100The Diaspora: Statements �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������392 SEANAD ÉIREANN Déardaoin, 23 Feabhra 2017 -

Prohibition of Conversion Therapies Bill 2018

An Bille um Thoirmeasc ar Theiripí Tiontúcháin, 2018 Prohibition of Conversion Therapies Bill 2018 Mar a tionscnaíodh As initiated [No. 33.6 of 2018] AN BILLE UM THOIRMEASC AR THEIRIPÍ TIONTÚCHÁIN, 2018 PROHIBITION OF CONVERSION THERAPIES BILL 2018 Mar a tionscnaíodh As initiated CONTENTS Section 1. Interpretation 2. Prohibition of Conversion Therapy 3. Criminalisation of Conversion Therapies 4. Short title and Commencement [No.33.6 of 2018] ACT REFERRED TO Mercantile Marine Act 1955 (No. 29) 2 AN BILLE UM THOIRMEASC AR THEIRIPÍ TIONTÚCHÁIN, 2018 PROHIBITION OF CONVERSION THERAPIES BILL 2018 Bill entitled An Act to prohibit conversion therapy, as a deceptive and harmful act or practice against 5 a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression. Be it enacted by the Oireachtas as follows: Interpretation 1. In this Act— “conversion therapy”— 10 (a) means any practice or treatment by any person that seeks to change, suppress and, or eliminate a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression; and (b) does not include any practice or treatment, which does not seek to change a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression, or 15 which— (i) provides assistance to an individual undergoing a gender transition; or (ii) provides acceptance, support and understanding of a person, or a facilitation of a person’s coping, social support and identity exploration and development, including sexual orientation-neutral interventions; 20 “sexual orientation” refers to each person’s capacity -

19Th Annual Report, 2015

BRITISH-IRISH PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY TIONÓL PARLAIMINTEACH NA BREATAINE AGUS NA HÉIREANN NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT Doc. No. 227 February 2015 CONTENTS Introduction Page 3 Membership of the Assembly Page 3 Political developments Page 3 The work of the Assembly Page 8 Forty-eighth plenary Conference (Kilmainham, Dublin) Page 8 Forty-ninth plenary Conference (Ashford, Kent and Flanders) Page 17 Steering Committee Page 24 Committees Page 24 Staffing Page 24 Prospects for 2015 Page 24 APPENDIX 1: Membership of the Assembly Page 25 APPENDIX 2: Reports, etc., approved by the Assembly Page 29 APPENDIX 3: Work of Committees Page 31 APPENDIX 4: Staffing of the Assembly Page 37 2 NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT THE WORK OF THE BRITISH-IRISH PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY IN 2014 Introduction 1. This is the nineteenth annual report of the Assembly since it was decided at the Plenary Session in May 1996 that such a Report should be made. This Report summarises the work of the Assembly during 2014. Membership of the Assembly 2. Following the significant turnover in membership in the 2010 and 2011, arising from general elections to the two sovereign parliaments and to the Scottish Parliament, National Assembly for Wales and Northern Ireland Assembly, 2014, like the two preceding years, was a period of stability in membership, with only minor changes. A list of Members and Associate Members is set out at Appendix 1. Political developments General Overview 3. The relationship between Ireland and Britain continued to deepen in 2014, the major highlight being the State Visit by President Michael D. Higgins and Mrs Sabina Higgins to the UK in April. -

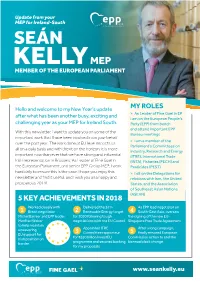

New Year Update 2019 Sean Kelly

Update from your MEP for Ireland-South SEÁN KELLY MEP MEMBER OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Hello and welcome to my New Year’s update MY ROLES after what has been another busy, exciting and > As Leader of Fine Gael in EP I am on the European People’s challenging year as your MEP for Ireland South. Party (EPP) front bench and attend important EPP With this newsletter, I want to update you on some of the Bureau meetings important work that I have been involved in on your behalf > I am a member of the over the past year. The work done at EU level impacts us Parliament’s Committees on all on a daily basis and with Brexit on the horizon, it is more Industry, Research and Energy important now than ever that we have strong and influential (ITRE), International Trade Irish representation in Brussels. As Leader of Fine Gael in (INTA), Fisheries (PECH) and the European Parliament, and senior EPP Group MEP, I work Pesticides (PEST) hard daily to ensure this is the case. I hope you enjoy this > I sit on the Delegations for newsletter and find it useful, and I wish you all a happy and relations with Iran, the United prosperous 2019! States, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 5 KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2018 Worked closely with Delivered the 32% As EPP lead negotiator on 1 Brexit negotiator 2 Renewable Energy target 4 South-East Asia, oversaw Michel Barnier and EPP leader for 2030 following tough the signing of the new EU- Manfred Weber negotiations with the EU Council Singapore Free Trade Agreement to help maintain unwavering 3 Appointed ITRE 5 After a long campaign, EU support for Committee rapporteur finally ensured European Irish position on for €650 billion InvestEU Commission action to end the border programme and secured backing biannual clock change for my proposals www.seankelly.eu RENEWABLE 32% of our energy in ENERGY Europe will This past year brought one of the proudest be renewable achievements of my political career. -

Seanad Éireann

SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE UM GHNÍOMHÚ AERÁIDE AGUS UM FHORBAIRT ÍSEALCHARBÓIN (LEASÚ), 2021 CLIMATE ACTION AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT (AMENDMENT) BILL 2021 LEASUITHE COISTE COMMITTEE AMENDMENTS [No. 39a of 2021] [2 July, 2021] SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE UM GHNÍOMHÚ AERÁIDE AGUS UM FHORBAIRT ÍSEALCHARBÓIN (LEASÚ), 2021 —AN COISTE CLIMATE ACTION AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT (AMENDMENT) BILL 2021 —COMMITTEE STAGE Leasuithe Amendments *Government amendments are denoted by an asterisk SECTION 3 1. In page 6, line 29, after “emissions” to insert “minus removals”. —Senators Regina Doherty, Garret Ahearn, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Maire Ní Bhroinn, Micheál Carrigy, Martin Conway, John Cummins, Emer Currie, Aisling Dolan, Seán Kyne, Tim Lombard, John McGahon, Joe O'Reilly, Mary Seery Kearney, Barry Ward, Lisa Chambers, Catherine Ardagh, Niall Blaney, Malcolm Byrne, Pat Casey, Shane Cassells, Lorraine Clifford-Lee, Ollie Crowe, Paul Daly, Aidan Davitt, Timmy Dooley, Mary Fitzpatrick, Robbie Gallagher, Gerry Horkan, Erin McGreehan, Eugene Murphy, Fiona O'Loughlin, Denis O'Donovan, Ned O'Sullivan, Diarmuid Wilson. 2. In page 6, to delete lines 34 and 35, and in page 7, to delete lines 1 to 3 and substitute the following: “ ‘climate justice’ means the requirement that decisions and actions taken, within the State and at the international level, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to the effects of climate change shall, in so far as it is practicable to do so— (a) support the people who are most affected by climate change but who have done the least to cause it and are the least equipped to adapt to its effects, (b) safeguard the most vulnerable persons, (c) endeavour to share the burdens and benefits arising from climate change, and (d) help to address inequality;”. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division).........................................................................................................................................