Statues:! Object!Oriented!Ontology!And!The!Figure!In!A! Sculptural!Practice!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Correlations Between Creativity In

1 ARTISTIC SCIENTISTS AND SCIENTIFIC ARTISTS: THE LINK BETWEEN POLYMATHY AND CREATIVITY ROBERT AND MICHELE ROOT-BERNSTEIN, 517-336-8444; [email protected] [Near final draft for Root-Bernstein, Robert and Root-Bernstein, Michele. (2004). “Artistic Scientists and Scientific Artists: The Link Between Polymathy and Creativity,” in Robert Sternberg, Elena Grigorenko and Jerome Singer, (Eds.). Creativity: From Potential to Realization (Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004), pp. 127-151.] The literature comparing artistic and scientific creativity is sparse, perhaps because it is assumed that the arts and sciences are so different as to attract different types of minds who work in very different ways. As C. P. Snow wrote in his famous essay, The Two Cultures, artists and intellectuals stand at one pole and scientists at the other: “Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension -- sometimes ... hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding... Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can't find much common ground." (Snow, 1964, 4) Our purpose here is to argue that Snow's oft-repeated opinion has little substantive basis. Without denying that the products of the arts and sciences are different in both aspect and purpose, we nonetheless find that the processes used by artists and scientists to forge innovations are extremely similar. In fact, an unexpected proportion of scientists are amateur and sometimes even professional artists, and vice versa. Contrary to Snow’s two-cultures thesis, the arts and sciences are part of one, common creative culture largely composed of polymathic individuals. -

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

THE NAKED APE By

THE NAKED APE by Desmond Morris A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd. PRINTING HISTORY Jonathan Cape edition published October 1967 Serialized in THE SUNDAY MIRROR October 1967 Literary Guild edition published April 1969 Transrvorld Publishers edition published May 1969 Bantam edition published January 1969 2nd printing ...... January 1969 3rd printing ...... January 1969 4th printing ...... February 1969 5th printing ...... June1969 6th printing ...... August 1969 7th printing ...... October 1969 8th printing ...... October 1970 All rights reserved. Copyright (C 1967 by Desmond Morris. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mitneograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 30 Bedford Square, London Idi.C.1, England. Bantam Books are published in Canada by Bantam Books of Canada Ltd., registered user of the trademarks con silting of the word Bantam and the portrayal of a bantam. PRINTED IN CANADA Bantam Books of Canada Ltd. 888 DuPont Street, Toronto .9, Ontario CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, 9 ORIGINS, 13 SEX, 45 REARING, 91 EXPLORATION, 113 FIGHTING, 128 FEEDING, 164 COMFORT, 174 ANIMALS, 189 APPENDIX: LITERATURE, 212 BIBLIOGRAPHY, 215 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is intended for a general audience and authorities have therefore not been quoted in the text. To do so would have broken the flow of words and is a practice suitable only for a more technical work. But many brilliantly original papers and books have been referred to during the assembly of this volume and it would be wrong to present it without acknowledging their valuable assistance. At the end of the book I have included a chapter-by-chapter appendix relating the topics discussed to the major authorities concerned. -

Industry and the Ideal

INDUSTRY AND THE IDEAL Ideal Sculpture and reproduction at the early International Exhibitions TWO VOLUMES VOLUME 1 GABRIEL WILLIAMS PhD University of York History of Art September 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis considers a period when ideal sculptures were increasingly reproduced by new technologies, different materials and by various artists or manufacturers and for new markets. Ideal sculptures increasingly represented links between sculptors’ workshops and the realm of modern industry beyond them. Ideal sculpture criticism was meanwhile greatly expanded by industrial and international exhibitions, exemplified by the Great Exhibition of 1851, where the reproduction of sculpture and its links with industry formed both the subject and form of that discourse. This thesis considers how ideal sculpture and its discourses reflected, incorporated and were mediated by this new environment of reproduction and industrial display. In particular, it concentrates on how and where sculptors and their critics drew the line between the sculptors’ creative authorship and reproductive skill, in a situation in which reproduction of various kinds utterly permeated the production and display of sculpture. To highlight the complex and multifaceted ways in which reproduction was implicated in ideal sculpture and its discourse, the thesis revolves around three central case studies of sculptors whose work acquired especial prominence at the Great Exhibition and other exhibitions that followed it. These sculptors are John Bell (1811-1895), Raffaele Monti (1818-1881) and Hiram Powers (1805-1873). Each case shows how the link between ideal sculpture and industrial display provided sculptors with new opportunities to raise the profile of their art, but also new challenges for describing and thinking about sculpture. -

Venetian Early Modern Single-Leaf Prints After Contemporary Sculpture: Questions of Form and Function

Matej Klemenčič VENETIAN EARLY MODERN SINGLE-LEAF PRINTS AFTER CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE: QUESTIONS OF FORM AND FUNCTION Riassunto rappresentare un singolo pezzo di scultu- ra e potevano essere realizzate per scopi Durante l’epoca moderna, sia la scultura di marketing, celebrativi o propagandistici classica che quella moderna furono spesso o altro ancora. L’articolo discute alcune di tradotte a stampa. Queste stampe sono state queste stampe singole, incise per illustrare pubblicate in diverse occasioni e utilizzate le opere dello scultore veneziano Antonio per vari scopi, spesso in serie con illustrazio- Corradini, e pubblicate a Venezia, Vienna e ni di importanti opere d’arte, come ad esem- Roma. Le incisioni vengono discusse in vi- pio a Roma, o come cataloghi di intere col- sta della loro funzione e dello sviluppo della lezioni di sculture. D’altra parte, potevano carriera di Corradini. Keywords: single-leaf prints, sculpture, Venice, Baroque, Antonio Corradini n one of his early drawings, Giambat- sculptor, therefore, whom Tiepolo wanted tista Tiepolo portrayed his colleagues to distinguish from the others, most prob- Iand friends, gathered sometime be- ably all of them painters. It would be in- tween 1716 and 1718 in a so-called “ac- triguing to identify him with one of the cademia del nudo”, a drawing academy younger Venetian sculptors of the time organised by Collegio dei pittori on Fon- but, unfortunately, there is little evidence damenta Nuove in contrada Santa Maria that would help us deduce his name.1 Formosa, in Venice (Fig. 1). Recently, the Even though our anonymous sculptor two figures on the right were identified as was carefully singled out by his contem- Gregorio Lazzarini (standing) and Antonio porary Tiepolo, at the time still a young, Balestra (sitting, and acting as a corrector), but already a very promising painter, this while the others remain anonymous. -

Primate Aesthetics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Primate Aesthetics Chelsea L. Sams University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sams, Chelsea L., "Primate Aesthetics" (2016). Masters Theses. 375. https://doi.org/10.7275/8547766 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/375 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2016 Department of Art PRIMATE AESTHETICS A Thesis Presented by CHELSEA LYNN SAMS Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________ Robin Mandel, Chair ___________________________________ Melinda Novak, Member ___________________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member ___________________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION For Christopher. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly indebted to my committee: Robin Mandel, for his patient guidance and for lending me his Tacita Dean book; to Melinda Novak for taking a chance on an artist, and fostering my embedded practice; and to Jenny Vogel for introducing me to the medium of performance lecture. To the longsuffering technicians Mikaël Petraccia, Dan Wessman, and Bob Woo for giving me excellent advice, and tolerating question after question. -

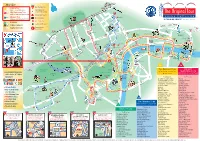

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

How to Find Us Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA

How to find us etc.venues Marble Arch is located on Edgware Road in the heart of the West End. By underground Central line to Marble Arch Station – when you exit the station, turn right on to Oxford Street and then right again on to Edgware Road walking past the Odeon Cinema. etc.venues Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA Marble Arch is in Garfield House, on the right hand side next to the Tescos. Tel: 020 7793 4200 Fax: 020 7793 4201 By train Email: [email protected] Paddington station is approximately 20 minutes walk. Use the Praed Street exit and turn left on Sat nav: 51.51542, -0.163319 to Praed Street and continue until you walk on to Edgware Road. Turn right onto Edgware Road and continue towards Marble Arch. GLO etc.venues Marble Arch is at the other end of A5 T S Y B Edgware Road on the left. Alternatively bus W B U R O CEST R R O routes 36 or 436 go from outside Paddington A W H N Garfield House on Praed Street and on to Edgware Road and S E T E ST R P 86-88 Edgware Road take approximately 10 minutes to Marble Arch. O RG GE London W2 2EA L G ACE EDG REAT By bus S TESCOTESCO EYMOU WAR etc.venues Marble Arch sits on many bus METROMETRO CU Y ST A41 KELE routes including 7, 10, 73, 98, 137, 390, 6, 23, E M E R R B BERL P E R 94, 159, 30, 94, 113, 159, 274, 2, 16, 36, 74, U P P RD L ACE 82, 148, 414, 436 AN 4 D A520 PL G H T ST Parking R A ST CONNAU M OU CE There is a NCP car park situated within close S EY proximity to Marble Arch - visit www.ncp.co.uk A5 ODEANODEAN MARBLEMARBLE MARBLEMARBLE ARCHARCH for more details. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association Society of Architectural Historians International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts Rosen and I, quite a few of our officers and committee members were able to attend and our gathering in Rome September 15, 2018 served too as an opportunity for the Membership, Outreach, and Development committee to meet and talk strategy. Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: We are, as always, deeply grateful to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for their support this past decade of these With a new semester (and a new academic year) important events. This year’s lecture was the last under our upon us once again, I write to provide a few highlights of current grant agreement and much of my time at the moment IAS activities in the past months. As ever, I am deeply is dedicated to finalizing our application to continue the grateful to all of our members and especially to those lecture series forward into next year and beyond. As I work who continue to serve on committees, our board, and to present the case for the value of these trans-continental executive council. It takes the hard work of a great exchanges, I appeal to any of you who have had the chance number of you to make everything we do possible. As I to attend this year’s lecture or one of our previous lectures to approach the end of my term as President this winter, I write to me about that experience. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Leaf and Brush Quadrants

Leaf and Brush Quadrants WE ATHE REND NB 52_B ETHA NIA RURA L HALL RD BURNSIDE KILS TROM SHORE MONTROYA L PINNA CLE BE THANIA RURAL HA LL RD_S B 52 WHISPERWOOD LO NGS HADOW SCOFIELD TO FIND YOUR QUADRANT: SK YEBUCKHAV EN AB BE Y AURORAGLEN JA MMIE PRES TWICK BA LMORAL HILL MIZ PAH CHURCH BANNOCKBURN MARTHA L HWY 66_NB 52 FLORENCE A T S V E SB 5 2_ VILLAGE OAK H HWY 66 WY 66 HWYUNIVE 66 RSIT Y S TAN L CRE STLA WNFERNTREE EYVIL A NOR FERNCRESLO NG CREE K T L E M SHUMATE VIRGINIA LAK E 1) Type your street name in the FIND box above the map FINWICK NY LON MATTHE WS LANDON THORNWOOD SUMM ER T RACE BE AVE R POND TONYA TURF WOOD HUCKLEBERRY NORM AN AMB ERWOOD SHERRI LYNN CHE SRIDGE WILLOWDALE BRAK ENWOOD ZIGLA R AVE RLA N BUSHB ERRY BUNNY GYDDIE RIVE R DALE MOS SGRE EN PHELP S BE THANIA-RURAIE L HALL MARTY BLUE RIDGE EA GLE CRE ST K HUNTING TON RIDGE GRAINWOOD B C ET HA I ALMA NIA -T TEETIME PHELP S OBA V STANLE YV ILLE K C KOGE R (For example: Enter only the name "MILLER" and CLIFFS IDE TOHARI C KE IL FA IRCRES T NITA OLD HOLLOW O BE LLE BE THANIAL PLACE O HARVE ST STO NE FOX CHAS E L CANNO Y I O B KILBV Y FAWN FORES T R R I W L BE THANIA OA KS A AUTUMN B L M NOE L LE WEY R T E B MEA DOW SWE ETB RIAR LE WBRIGHT LEA F O S ROCK S PRING O HARPWE LL BROWNWOOD O E RENWOOD P O WHITEOA K R D P N I LO RE N ECHO HARRINGTON VILLAGE C ANGEL OAK S H STAGE COACH O STONE WA Y LO DGE CRES T K I W ROLLING GREEN O NB 52 LESLIE T CORA L A NOT "MILLER STREET") POLA RIS O HANES M ILL RD_NB 52 MERRY DALE L R PE NNE R RE FLE CT ION T L MURRAY SB 52_W HA NES MILL