Volcanic Fire and Glacial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenic Landforms of Virginia

Vol. 34 August 1988 No. 3 SCENIC LANDFORMS OF VIRGINIA Harry Webb . Virginia has a wide variety of scenic landforms, such State Highway, SR - State Road, GWNF.R(T) - George as mountains, waterfalls, gorges, islands, water and Washington National Forest Road (Trail), JNFR(T) - wind gaps, caves, valleys, hills, and cliffs. These land- Jefferson National Forest Road (Trail), BRPMP - Blue forms, some with interesting names such as Hanging Ridge Parkway mile post, and SNPMP - Shenandoah Rock, Devils Backbone, Striped Rock, and Lovers Leap, National Park mile post. range in elevation from Mt. Rogers at 5729 feet to As- This listing is primarily of those landforms named on sateague and Tangier islands near sea level. Two nat- topographic maps. It is hoped that the reader will advise ural lakes occur in Virginia, Mountain Lake in Giles the Division of other noteworthy landforms in the st& County and Lake Drummond in the City of Chesapeake. that are not mentioned. For those features on private Gaps through the mountains were important routes for land always obtain the owner's permission before vis- early settlers and positions for military movements dur- iting. Some particularly interesting features are de- ing the Civil War. Today, many gaps are still important scribed in more detail below. locations of roads and highways. For this report, landforms are listed alphabetically Dismal Swamp (see Chesapeake, City of) by county or city. Features along county lines are de- The Dismal Swamp, located in southeastern Virginia, scribed in only one county with references in other ap- is about 10 to 11 miles wide and 15 miles long, and propriate counties. -

Wilburn Ridge/Pine Mountain - Grayson Highlands, Virginia

Wilburn Ridge/Pine Mountain - Grayson Highlands, Virginia Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 14.2 mls Hiking Time: 7.0 hours plus a 1 hour for lunch and breaks Elev. Gain: 2,225 ft Parking: Park at the Massie Gap parking area Consistently mentioned as one of the top sections along the Appalachian Trail and arguably boasting the finest views in the Southeast, the Appalachian Trail through the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area should be on everyone’s must-do list. This loop samples the best parts of this region in one fantastic day hike. The prime starting location for entering these mountains is Grayson Highlands State Park, but this hike will avoid most of the crowds while delivering the same views. From the Massie Gap parking area you will climb up to the Appalachian Trail heading north away from the pony-watching congregation area. After diving through the Wilson Creek basin, the AT climbs through the Little Wilson Creek Wilderness and the flanks of Stone Mountain with top-notch views for miles on open ridges. From the Scales compound the AT crosses through conifer forest before you leave the AT to make your way to Rhododendron Gap. The Pine Mountain Trail connects to the AT where you have the option of an out-and-back to Mount Rogers or a shorter return to the parking lot. Either way, the sections near Rhododendron Gap offer more top of the world views in all directions. The AT straddles open ridges above 5,000 feet and feels like a trail from another part of the country. -

2016 Smokies Trip Planner

National Park Service Great Smoky Mountains National Park U.S. Department of the Interior 2016 Smokies Trip Planner Tips on Auto Touring in the National Park Great Smoky Mountains National Park Clingmans Dome Road (7 miles, open encompasses over one-half million acres, For updated park weather April 1-Nov 30.) making it one of the largest natural areas in and road closure This spur road follows a high ridge to a paved the east. An auto tour of the park offers walking trail that leads 0.5 mile to the park’s scenic views of mountain streams, weathered information highest peak. Highlights are mountain views historic buildings, and forests stretching to call (865) 436-1200 and the cool, evergreen, spruce-fir forest. the horizon. Little River Road (18 miles) There are over 270 miles of road in the The following is a partial listing of some of This road parallels the Little River from Smokies. Most are paved, and even the gravel the park’s most interesting roads. To purchase Sugarlands Visitor Center to near Townsend, roads are maintained in suitable condition for maps and road guides, call (888) 898-9102 or TN. Highlights include the river, waterfalls, standard two-wheel drive automobiles. visit http://shop.smokiesinformation.org. and wildflowers. Driving in the mountains presents new chal- Newfound Gap Road (33 miles) Roaring Fork Motor Nature Trail (6 miles, lenges for many drivers. When going down- This heavily used highway crosses Newfound open March 25-Nov 30. Buses and RVs are hill, shift to a lower gear to conserve your Gap (5,046' elevation) to connect Cherokee, not permitted on the motor nature trail.) brakes and avoid brake failure. -

Catoctin Formation

Glimpses of the Past: THE GEOLOGY of VIRGINIA The Catoctin Formation — Virginia is for Lavas Alex Johnson and Chuck Bailey, Department of Geology, College of William & Mary Stony Man is a high peak in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains that tops out at just over 1200 m (4,000’). Drive south from Thornton Gap along the Skyline Drive and you’ll see the impressive cliffs of Stony Man’s northwestern face. These are the cliffs that give the mountain its name, as the cliffs and slopes have a vague resemblance to a reclining man’s forehead, eye, nose, and beard. Climb to the top and you’ll see peculiar bluish-green rocks exposed on the summit that are ancient lava flows, part of a geologic unit known as the Catoctin Formation. From the presidential retreat at Camp David to Jefferson’s Monticello, from Harpers Ferry to Humpback Rocks, the Catoctin Formation underlies much of the Blue Ridge. This distinctive geologic unit tells us much about the long geologic history of the Blue Ridge and central Appalachians. Stony Man’s summit and northwestern slope, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Cliffs expose metabasaltic greenstone of the Neoproterozoic Catoctin Formation. (CMB photo). Geologic cross section of Stony Man summit area (modified from Badger, 1999). The Catoctin Formation was first named by Arthur Keith in 1894 and takes its name for exposures on Catoctin Mountain, a long ridge that stretches from Maryland into northern Virginia. The word Catoctin is rooted in the old Algonquin term Kittockton. The exact meaning of the term has become a point of contention; among historians the translation “speckled mountain” is preferred, however local tradition holds that that Catoctin means “place of many deer” (Kenny, 1984). -

COWPASTURE RIVER PRESERVATION ASSOCIATION, ET AL., Respondents

Nos. 18-1584 & 18-1587 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE, ET AL., Petitioners, AND ATLANTIC COAST PIPELINE, LLC, Petitioner, v. COWPASTURE RIVER PRESERVATION ASSOCIATION, ET AL., Respondents. __________ On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit __________ BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS __________ AUSTIN D. GERKEN, JR. MICHAEL K. KELLOGG AMELIA BURNETTE Counsel of Record J. PATRICK HUNTER GREGORY G. RAPAWY SOUTHERN ENVIRONMENTAL BRADLEY E. OPPENHEIMER LAW CENTER KELLOGG, HANSEN, TODD, 48 Patton Avenue, Suite 304 FIGEL & FREDERICK, P.L.L.C. Asheville, NC 28801 1615 M Street, N.W., Suite 400 (828) 258-2023 Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 326-7900 ([email protected]) Counsel for Respondents Cowpasture River Preservation Association, Highlanders for Responsible Development, Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, Shenandoah Valley Network, and Virginia Wilderness Committee January 15, 2020 (Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover) GREGORY BUPPERT SOUTHERN ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CENTER 201 West Main Street, Suite 14 Charlottesville, VA 22902 (434) 977-4090 Counsel for Respondents Cowpasture River Preservation Association, Highlanders for Responsible Development, Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, Shenandoah Valley Network, and Virginia Wilderness Committee NATHAN MATTHEWS SIERRA CLUB ENVIRONMENTAL LAW PROGRAM 2101 Webster Street, Suite 1300 Oakland, CA 94612 (415) 977-5695 Counsel for Respondents Sierra Club and Wild Virginia, Inc. QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the United States Forest Service has statutory authority under the Mineral Leasing Act to grant a gas pipeline right-of-way across the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. ii RULE 29.6 STATEMENTS Pursuant to Rule 29.6 of the Rules of this Court, respondents Cowpasture River Preservation Associa- tion, Highlanders for Responsible Development, Shen- andoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, Shenandoah Valley Network, Sierra Club, Virginia Wilderness Committee, and Wild Virginia, Inc. -

Mt Rogers/Wilburn Ridge Hike

Mt Rogers/Wilburn Ridge - Troutdale, Virginia Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 21.5 mls Hiking Time: 2.5 Days Elev. Gain: Day One – 1441 feet, Day Two – 2963 feet, Day Three – 715 feet Optional Mt. Rogers Peak – 287 feet Parking: Park at the Grindstone Campground. $5 per night parking fee. 36.68664, 81.54285 By Trail Contributor: Michael Gergely This hike is an extended version of the Wilburn Ridge/Pine Mountain loop that includes two overnight stays and an optional side trip to the Mount Rogers summit. This 2.5 day itinerary is set up for hikers with a long drive on the first and last day of the hike. Alternatively the hike can be completed in 2 days by staying overnight near the Scales or Wise Shelter, or by using the Pine Mountain Trail to shorten the route. The Mount Rogers/Grayson Highlands area is one of the premier hiking spots on the East Coast, featuring sweeping vistas and highland meadows. The majority of the hike follows the Appalachian Trail from VA Route 603 to Deep Gap as it detours through the park to take in the stunning views. Wild ponies and local herds of cattle are allowed to range throughout the park to help manage and maintain the open balds. The hike starts out from the Grindstone Campground, which charges $3/night per vehicle for backpackers parking there. There are also two free parking lots at the Fairwood Valley and Fox Creek trailheads on Rte 603 - however, other hikers have reported car break-ins at these locations in the past. -

Cumberland Gap Master Plan and Trailhead Development Plan

Cumberland Gap Master Plan and Trailhead Development Plan Community Development Partners Cumberland Gap Master Plan and Trailhead Development Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Community Vision ............................................................................. 33 Executive Summary ............................................................................. 1 Steering Committee ........................................................................ 33 The Historic Town of Cumberland Gap .......................................... 2 Cumberland Gap Master Plan Survey ......................................... 33 Community Need................................................................................. 3 Public Meetings .............................................................................. 35 What is the Cumberland Gap Master Plan? ..................................... 5 Vision Statement ............................................................................ 36 How Will the Plan Be Used? .......................................................... 6 Mentor Communities ......................................................................... 37 Plan Consistency .............................................................................. 7 Banner Elk ....................................................................................... 37 Project Area ...................................................................................... 8 Damascus ....................................................................................... -

190 Public Law 89.437-May 31, 1966 [80 Stat

190 PUBLIC LAW 89.437-MAY 31, 1966 [80 STAT. Public Law 89-437 May 31, 1966 AN ACT [H. R. 12262] rj^^ continue until the close of June 30, 1969, the existing suspension of duty on certain copying shoe lathes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and Houae of Representatives of the Duty iulpln- United States of America m Congress assembled, That (a) item 911.70 sion. of the Tariff Schedules of the United States (19 LT.S.C, sec. 1202, item 7 8^sfaf 231''^'*' -^ll-^O) is amended by striking out "On or before 6/30/66" and insert ing in lieu thereof "On or before 6/80/69". (b) The amendment made by subsection (a) shall apply with respect to articles entered, or withdrawn from warehouse, for con sumption, after June 30,1966. Approved May 31, 1966. Public Law 89-438 May 31, 1966 AN ACT [H. R. 103 66] rp^y establish the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area in the Jefferson National Forest in Virginia, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Mount Rogers United States of America in Congress assembled. That, in order to tion Area, Va. provide for the public outdoor recreation use and enjoyment of the area in the vicinity of Mount Rogers, the highest mountain in the State of Virginia, and to the extent feasible the conservation of scenic, scien tific, historic, and other values of the area, the Secretary of Agriculture shall establish the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area in the Jefferson National Forest in the State of Virginia. -

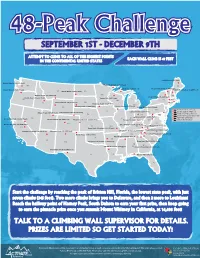

PRINT 48-Peak Challenge

48-Peak Challenge SEPTEMBER 1ST - DECEMBER 9TH ATTEMPT TO CLIMB TO ALL OF THE HIGHEST POINTS EACH WALL CLIMB IS 47 FEET IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES Katahdin (5,268 feet) Mount Rainier (14,411 feet) WA Eagle Mountain (2,301 feet) ME Mount Arvon (1,978 feet) Mount Mansfield (4,393 feet) Mount Hood (11,239 feet) Mount Washington (6,288 feet) MT White Butte (3,506 feet) ND VT MN Granite Peak (12,799 feet) NH Mount Marcy (5,344 feet) Borah Peak (12,662 feet) OR Timms Hill (1,951 feet) WI NY MA ID Gannett Peak (13,804 feet) SD CT Hawkeye Point (1,670 feet) RI MI Charles Mount (1,235 feet) WY Harney Peak (7,242 feet) Mount Davis (3,213 feet) PA CT: Mount Frissell (2,372 feet) IA NJ DE: Ebright Azimuth (442 feet) Panorama Point (5,426 feet) Campbell Hill (1,549 feet) Kings Peak (13,528 feet) MA: Mount Greylock (3,487 feet) NE OH MD DE MD: Backbone Mountain (3360 feet) Spruce Knob (4,861 feet) NV IN NJ: High Point (1,803 feet) Boundary Peak (13,140 feet) IL Mount Elbert (14,433 feet) Mount Sunflower (4,039 feet) Hoosier Hill (1,257 feet) WV RI: Jerimoth Hill (812 feet) UT CO VA Mount Whitney (14,498 feet) Black Mountain (4,139 feet) KS Mount Rogers (5,729 feet) CA MO KY Taum Sauk Mountain (1,772 feet) Mount Mitchell (6,684 feet) Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet) Wheeler Peak (12,633 feet) Clingmans Dome (6,643 feet) NC Sassafras Mountain (3,554 feet) Black Mesa (4,973 feet) TN Woodall Mountain (806 Feet) OK AR SC AZ NM Magazine Mountain (2,753 feet) Brasstown Bald (4,784 feet) GA AL Driskill Mountain (535MS feet) Cheaha Mountain (2,405 feet) Guadalupe Peak (8,749 feet) TX LA Britton Hill (345 feet) FL Start the challenge by reaching the peak of Britton Hill, Florida, the lowest state peak, with just seven climbs (345 feet). -

Resource Management Plan, Appalachian National Scenic Trail

Appalachian National Scenic Trail Resource Management Plan – September 2008 – Recommended: Casey Reese, Interdisciplinary Physical Scientist, Appalachian National Scenic Trail Recommended: Kent Schwarzkopf, Natural Resource Specialist, Appalachian National Scenic Trail Recommended: Sarah Bransom, Environmental Protection Specialist, Appalachian National Scenic Trail Recommended: David N. Startzell, Executive Director, Appalachian Trail Conference Approved: Pamela Underhill, Park Manager, Appalachian National Scenic Trail Concur: Chris Jarvi, Associate Director, Partnerships, Interpretation and Education, Volunteers, and Outdoor Recreation Foreword: Purpose of the Resource Management Plan The purpose of this plan – the Appalachian Trail Resource Management Plan – is to document the Appalachian National Scenic Trail’s natural and cultural resources and describe and set priorities for management, monitoring, and research programs to ensure that these resources are properly protected and cared for. This plan is intended to provide a medium-range, 10-year strategy to guide resource management activities conducted by the Appalachian Trail Park Office and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (and other partners who wish to participate) for the next decade. It is further intended to establish priorities for funding projects and programs to manage and protect the Trail’s natural and cultural resources. In some cases, this plan recognizes and identifies the need for preparation of future action plans to deal with specific resource management issues. These future plans will be tiered to this document. Management objectives outlined in the Appalachian Trail Resource Management Plan are consistent with the Appalachian Trail Comprehensive Plan (1981, re-affirmed 1987), the Appalachian Trail Statement of Significance (2000), and the Appalachian Trail Strategic Plan (2001, updated 2005). These objectives also are based on the resource protection mandates stated in the NPS Organic Act of 1916 and the Trail’s enabling legislation, the National Trails System Act. -

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Report No. 70-1-44 February 1970 5230 STATUS OF THE BALSAM WOOLLY APHID IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS-1969 By John L. Rauschenberger and H.L. Lambert U.S. Fore st Service Asheville, North Carolina ABSTRACT During 1969, established infestations of the balsam woolly aphid on State, Private and Federal lands continued to thrive and new ones were detected. Only the fir type of Mount Rogers in Virginia continues through 1969 to be free of aphid infestation. Emphasis was placed, during 1969, on establish ment of protection boundaries around accessible, high value stands of fir. Protective spraying has been discontinued and the policy has become one of spraying only actively infested trees. Intensive trapping procedures carried out in the respective protection areas revealed two areas of infestations on Roan Mountain, one on Mount Mitchell and also infestations on fir seed trees in the Linville River Forestry Facility at Crossnore, North Carolina. The aerial and ground phase of the 1969 balsam woolly aphid evaluation covered 60,000 acres of host type. INTRODUCTION The balsam woolly aphid, Adel r;es pl ce ae Ratz. was accidentally introduced into North America in the early 1900' s and detected in North Garolina in 195 7 ( Speers, 19 5 8). Since that time the aphid has become established in every major area of host fir type in the three state area of North Garolina, Virginia and Tennessee with the single exception of a 500-acre fir stand on Mount Rogers National Recreation Area in Virginia ( Fig. 1). The two native species of fir which serve as host in the Southern Appalachians are Fraser, Ables fras e rt ( Pursh. -

Field Guide to the Geology of Parts of the Appalachian Highlands and Adjacent Interior Plains

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 262 974 SE 046 186 AUTHOR McKenzie, Garry D.; Utgard, Russell 0. TITLL Field Guide to the Geology of Parts of the Appalachian Highlands and Adjacent Interior Plains. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Geology and Mineralogy. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 140p.; Document contains several colored maps which may not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *College Science; *Field Trips; *Geology; Higher Education; *Science Activities; Science Education ABSTRACT This field guide is the basis for a five-day, 1000-mile trip through six states and six geomorphic provinces. The trip and the pre- and post-trip exercises included in the guide constitute a three credit course at The Ohio State University entitled "Field Geology for Science Teachers." The purpose of the trip is tc study the regional geology, which ranges from Quaternary glacial deposits through a folded and faulted Paleozoic terrane to an igneous and metamorphic terrane. Study of geomorphological features and the application of geomorphology to aid in understanding the geology are also important objectives of the field trip. The trip also provides the opportunity to observe and study relationships between the geology of an area, its natural resources, and the culture and life styles of the inhabitants. For teachers participating in the trip, it demonstrates the advantages of teaching a subject like geology in the field and the nature of field evidence. In addition to a road log and stop descriptions, the guide includes a very brief introduction to the geology of the Appalachian Highlands and the Interior Plains, a review of geological terms, concepts, and techniques, and notes on preparing for and running field trips.