The Battlefields of Disagreement and Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗

Country of Women? Repercussions of the Triple Alliance War in Paraguay∗ Jennifer Alix-Garcia Laura Schechter Felipe Valencia Caicedo Oregon State University UW Madison University of British Columbia S. Jessica Zhu Precision Agriculture for Development April 5, 2021 Abstract Skewed sex ratios often result from episodes of conflict, disease, and migration. Their persistent impacts over a century later, and especially in less-developed regions, remain less understood. The War of the Triple Alliance (1864{1870) in South America killed up to 70% of the Paraguayan male population. According to Paraguayan national lore, the skewed sex ratios resulting from the conflict are the cause of present-day low marriage rates and high rates of out-of-wedlock births. We collate historical and modern data to test this conventional wisdom in the short, medium, and long run. We examine both cross-border and within-country variation in child-rearing, education, labor force participation, and gender norms in Paraguay over a 150 year period. We find that more skewed post-war sex ratios are associated with higher out-of-wedlock births, more female-headed households, better female educational outcomes, higher female labor force participation, and more gender-equal gender norms. The impacts of the war persist into the present, and are seemingly unaffected by variation in economic openness or ties to indigenous culture. Keywords: Conflict, Gender, Illegitimacy, Female Labor Force Participation, Education, History, Persistence, Paraguay, Latin America JEL Classification: D74, I25, J16, J21, N16 ∗First draft May 20, 2020. We gratefully acknowledge UW Madison's Graduate School Research Committee for financial support. We thank Daniel Keniston for early conversations about this project. -

Paraguay: in Brief

Paraguay: In Brief June S. Beittel Analyst in Latin American Affairs August 31, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44936 Paraguay: In Brief Summary Paraguay is a South American country wedged between Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil. It is about the size of California but has a population of less than 7 million. The country is known for its rather homogenous culture—a mix of Latin and Guarani influences, with 90% of the population speaking Guarani, a pre-Columbian language, in addition to Spanish. The Paraguayan economy is one of the most agriculturally dependent in the hemisphere and is largely shaped by the country’s production of cattle, soybeans, and other crops. In 2016, Paraguay grew by 4.1%; it is projected to sustain about 4.3% growth in 2017. Since his election in 2013, President Horacio Cartes of the long-dominant Colorado Party (also known as the Asociación Nacional Republicana [ANC]), has moved the country toward a more open economy, deepening private investment and increasing public-private partnerships to promote growth. Despite steady growth, Paraguay has a high degree of inequality and, although poverty levels have declined, rural poverty is severe and widespread. Following Paraguay’s 35-year military dictatorship in the 20th century (1954-1989), many citizens remain cautious about the nation’s democracy and fearful of a return of patronage and corruption. In March 2016, a legislative initiative to allow a referendum to reelect President Cartes (reelection is forbidden by the 1992 constitution) sparked large protests. Paraguayans rioted, and the parliament building in the capital city of Asunción was partially burned. -

The Grandchildren of Solano López: Frontier and Nation in Paraguay, 1904-1936 by Bridget María Chesterton David M

International Social Science Review Volume 90 | Issue 1 Article 6 2015 The Grandchildren of Solano López: Frontier and Nation in Paraguay, 1904-1936 by Bridget María Chesterton David M. Carletta Marist Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr Part of the Anthropology Commons, Communication Commons, Economics Commons, Geography Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Carletta, David M. (2015) "The Grandchildren of Solano López: Frontier and Nation in Paraguay, 1904-1936 by Bridget María Chesterton," International Social Science Review: Vol. 90: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol90/iss1/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Social Science Review by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. Carletta: The Grandchildren of Solano López Chesterton, Bridget María. The Grandchildren of Solano López: Frontier and Nation in Paraguay, 1904-1936. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2013. xii + 179 pages. Cloth. $50.00. After winning independence from Spain in the early nineteenth century, Paraguayans and Bolivians failed to agree over the boundary that separated them in the sparsely inhabited Chaco Boreal, a harsh wilderness of about 100,000 square miles between the Pilcomayo River and the Paraguay River. By the early twentieth century, interest in the Chaco Boreal increased. Defeated by Chile in the War of Pacific (1879-1883), Bolivia had lost control of disputed territory on the Pacific coast and hence access to the sea. -

Biochemical Comparison of Two Hypostomus Populations (Siluriformes, Loricariidae) from the Atlântico Stream of the Upper Paraná River Basin, Brazil

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 32, 1, 51-57 (2009) Copyright © 2009, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Research Article Biochemical comparison of two Hypostomus populations (Siluriformes, Loricariidae) from the Atlântico Stream of the upper Paraná River basin, Brazil Kennya F. Ito1, Erasmo Renesto1 and Cláudio H. Zawadzki2 1Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Departamento de Biologia Celular e Genética, Maringá, PR, Brazil. 2Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Departamento de Biologia/Nupelia, Maringá, PR, Brazil. Abstract Two syntopic morphotypes of the genus Hypostomus - H. nigromaculatus and H. cf. nigromaculatus (Atlântico Stream, Paraná State) - were compared through the allozyme electrophoresis technique. Twelve enzymatic systems (AAT, ADH, EST, GCDH, G3PDH, GPI, IDH, LDH, MDH, ME, PGM and SOD) were analyzed, attributing the score of 20 loci, with a total of 30 alleles. Six loci were diagnostic (Aat-2, Gcdh-1, Gpi-A, Idh-1, Ldh-A and Mdh-A), indicating the presence of interjacent reproductive isolation. The occurrence of few polymorphic loci acknowledge two morphotypes, with heterozygosity values He = 0.0291 for H. nigromaculatus and He = 0.0346 for H. cf. nigromaculatus. FIS statistics demonstrated fixation of the alleles in the two morphotypes. Genetic identity (I) and dis- tance (D) of Nei (1978) values were I = 0.6515 and D = 0.4285. The data indicate that these two morphotypes from the Atlântico Stream belong to different species. Key words: allozymes, Hypostomus nigromaculatus, fish genetics, genetic distance and polymorphism. Received: March 18, 2008; Accepted: September 5, 2008. Introduction to settle doubts regarding the taxonomic status of undes- The Neotropical region, encompassing southern Me- cribed species of the Brazilian ichthyofauna (Renesto et al., xico and Central and South America, possesses the richest 2000, 2001, 2007; Zawadzki et al., 2000, 2004). -

Adequacy of Soil Studies in Paraguay, Bolivia and Perú

Wo 7 es ources Reports Noversr-December, O FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS :74 r Also issued in this series: Report of the First Meeting of the Advisory Panel on the Soil Map of the World, Rome, 19-23 June 1961. Report of the First Meeting on Soil. Survey, Correlation and Interpretation for Latin America, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 28-31 May 1962. Report of the First Soil Correlation Seminar for Europe, Moscow, U.S.S.R., 16-28 July 1962. Report of the First Soil Correlation Seminar for South and Central Asia, Tashkent, Uzbekistan,U.S.S.R., 14 September-2_ October 1962. Report of the Fourth Session of the Working Party on Soil Classification and Survey (Subcommission on Land and Water Use of the European Com- mission on Agriculture), Lisbon, Portugal, 6-10 March 1963. Report of the Second Meeting of the Advisory Panel on the Soil Map of the World, Rome, 9-11 July 1963. Report of the Second Soil Correlation SeminarforEurope,Bucharest, Romania, 29 July-6 August 1963. Report of the Third Meeting of the Advisory Panel on the Soil Map of the World, Paris, 3 January 1964. 0 MACYOFOIl STUDILS IN PADrGUAY BOLIVIA AND PERU. Ileport of FAO Mission, NovemberDeoember 1963 D D AGRICULTURAL ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROME 1964 11721 " 80'1 '6" TIIYri H P1 1' A (1 BOldVIA. AND MIRD IYINTIWrlf; Fagc! FCYJi .1)mo0o0.604/A0eoe000m0ou.06006o0.00.00900000000,..0e00000Q eee.m0000mOoeuw,.,voseesoo000040oGem00.4,60000m000000 2. -4! PARAGUAY SUMT Y OF FITT:DINGS AND MCOMMENDATIONS " " o 4- SOURCES OF INFORMATION0000000e00000.10e000000000000000000 7 PRYSIC ("TMI OTERISTICS OF PARAGUAY Location00au0o.0000'00000000,0000.00000000000 7 TOP( aphy and-Landforma00 0400 4000 04044.40 4040 0 * 00 7 Gnology 8 Ca:mate,0e40.0000e0040 om ow« marOneoeceeogo.oee001,0q90.0.9 8 VC) gat ation 000000. -

Overview of Parana Delta1 Parana River

Overview of Parana Delta1 Author: Verónica M.E. Zagare2 Parana River The Parana River is considered the third largest river in the American Continent, after the Mississippi in the United States and the Amazonas in Brazil. It is located in South America and it runs through Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina, where it flows into the Río de la Plata. Its length is 2570 Km and its basin surface is around 1.51 million km2. The two initial tributaries of the Parana are the Paranaiba River and the Grande River, both in Brazil, but the most important tributary is the Paraguay River, located in homonymous country. In comparison with other rivers, the Paraná is about half the length of the Mississippi River (6211 km), but it has similar flow. Parana River’s mean streamflow is 18500 m3/s (Menendez, 2002) and Mississippi’s flow is 17704 m3/s. Thus, the Parana has twice the length of the Rhine (1320 km), but it has 8 times its flow (2300 m3/s). Figure 1: Parana River location. Source: Zagare, V. (2010). 1 Developed for the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works (Trip to Parana Delta, August 2011). 2 Architect and MsC in Urban Economics; PhD candidate (Department of Urbanism, Delft University of Technology). Delta Alliance contact in Argentina. Email: v.m.e.zagare @tudelft.nl Through the Parana Delta and the Rio de la Plata estuary drains to the Atlantic Ocean the second major hydrographic basin of South America (La Plata Basin). From a geologic perspective, the complex system of the delta and the estuary are considered a dynamic sedimentary geologic- hydrologic unit which has a vital relevance not only for the region -a high populated area with more than 22 million inhabitants- but also for the hydrology of South American continent. -

Materiales Complementarios 2021

MATERIALES COMPLEMENTARIOS 2021 Comprensión y Producción de Textos en Artes | Ciclo introductorio Escuela Universitaria de Artes | Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Lic. María de la Victoria Pardo ÍNDICE Capítulo I Concepto de autor María Moreno: La intrusa 3 Ficción, mímesis y verosimilitud El incendio del Museo del Prado 6 Discurso periodístico COVID-19 en los medios 9 Capítulo II Narración y descripción Jorge Luis Borges y Margarita Guerrero: La anfisbena 23 Laura Malosetti Costa: Comentario sobre Le lever de la bonne 24 Juan José Saer: El limonero real 26 Autobiografía Roberto Arlt 29 César Tiempo 30 Relato testimonial Marta Dillon: Aparecida 31 Capítulo IV Ensayo Juan Coulasso: Reinventar el teato 36 Mercedes Halfon: No es arte, es dinamita 39 Ana Longoni: (Con)Textos para el GAC 44 Boris Groys: Internet, la tumba de la utopía posmoderna 51 Martha Nanni: Ramona 61 Ticio Escobar: Tekopora. Ensayo curatorial 68 Chimamanda Adichie: El peligro de una sola historia 95 2 Capítulo I | Concepto de autor María Moreno: “La intrusa” Página 12 | 7 de marzo de 2017 (versión libre en honor al paro del 8 de marzo) Yo supe la historia por una muchacha que tiene su parada frente a la estación de ómnibus, en una esquina de Balvanera, no viene al caso decir cuál. Se la había contado, su tátara tátara tía abuela, la compañera de vida de Juliana Burgos, así dijo. Con la contada por Santiago Dabove a Borges y la que Borges a su vez oyó en Turdera tiene “pequeñas variaciones y divergencias”. La escribo previendo que cederé a la tentación literaria de acentuar o agregar algún pormenor como Borges declaró que haría en la primer página de La intrusa. -

1 Regional Project/Programme

REGIONAL PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Climate change adaptation in vulnerable coastal cities and ecosystems of the Uruguay River. Countries: Argentina Republic and Oriental Republic of Uruguay Thematic Focal Area1: Disaster risk reduction and early warning systems Type of Implementing Entity: Regional Implementing Entity (RIE) Implementing Entity: CAF – Corporación Andina de Fomento (Latin American Development Bank) Executing Entities: Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Argentina and Ministry of Housing, Land Planning and Environment of Uruguay. Amount of Financing 13.999.996 USD (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) Requested: 1 Project / Programme Background and Context: 1.1. Problem to be addressed – regional perspective 1. The Project’s implementation is focused on the lower Uruguay river´s littoral area, specifically in the vulnerable coastal cities and ecosystems in both Argentinean and Uruguayan territories. The lower Uruguay river´s littoral plays a main role being a structuring element for territorial balance since most cities and port-cities are located in it, with borther bridges between the two countries (Fray Bentos – Gualeguaychú; Paysandú – Colón; and Salto – Concordia). The basin of the Uruguay river occupies part of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, with a total area of approximately 339.000 Km2 and an average flow rate of 4.500 m3 s-1. It´s origin is located in Serra do Mar (Brazil), and runs for 1.800 Km until it reaches Río de la Plata. A 32% of its course flows through Brazilian territory, 38% forms the Brazil-Argentina boundary and a 30% forms the Argentina-Uruguay boundary. 2. The Project’s area topography is characterized by a homogeneous landform without high elevations, creating meandric waterways, making it highly vulnerable to floods as one of its main hydro-climatic threats, which has been exacerbated by the effects of climate change (CC). -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001). -

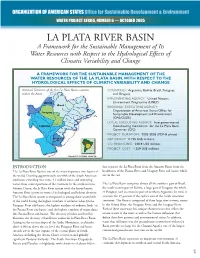

LA PLATA RIVER BASIN a Framework for the Sustainable Management of Its Water Resources with Respect to the Hydrological Effects of Climatic Variability and Change

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES Office for Sustainable Development & Environment WATER PROJECT SERIES, NUMBER 6 — OCTOBER 2005 LA PLATA RIVER BASIN A Framework for the Sustainable Management of Its Water Resources with Respect to the Hydrological Effects of Climatic Variability and Change A FRAMEWORK FOR THE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF THE WATER RESOURCES OF THE LA PLATA BASIN,WITH RESPECT TO THE HYDROLOGICAL EFFECTS OF CLIMATIC VARIABILITY AND CHANGE National Territories of the five La Plata Basin countries COUNTRIES: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, within the Basin and Uruguay IMPLEMENTING AGENCY: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) REGIONAL EXECUTING AGENCY: Organization of American States/Office for Sustainable Development and Environment (OAS/OSDE) LOCAL EXECUTING AGENCY: Intergovernmental Coordinating Committee for the La Plata Basin Countries (CIC) PROJECT DURATION: 2003-2005 (PDF-B phase) GEF GRANT: 0.725 US$ millions CO-FINANCING: 0.834 US$ millions PROJECT COST: 1.559 US$ millions INTRODUCTION that separate the La Plata Basin from the Amazon Basin, form the The La Plata River Basin is one of the most important river basins of headwaters of the Parana River and Uruguay River sub-basins which the world. Draining approximately one-fifth of the South American rise in the east. continent, extending over some 3.1 million km2, and conveying waters from central portions of the continent to the south-western The La Plata Basin comprises almost all the southern part of Brasil, Atlantic Ocean, the la Plata River system rivals the better-known the south-eastern part of Bolivia, a large part of Uruguay, the whole Amazon River system in terms of its biological and habitat diversity. -

Colombia Ante La Guerra Del Paraguay Contra La Triple Alianza

Memoria Conferencia: Colombia ante la guerra del Paraguay contra la Triple Alianza Conferencista S.E. Embajador Ricardo Scavone Yegros Embajador del Paraguay en Colombia El señor Embajador inició su intervención con una breve presentación de la ubicación geográfica del Paraguay, su posición estratégica en la Cuenca del Plato y la importancia que representa para este país la energía hidroeléctrica y la navegación fluvial. Se presentaron tres etapas claves en las relaciones internacionales del Paraguay: primero, un periodo en el que la diplomacia paraguaya estuvo enfocada en el reconocimiento de su independencia. Si bien Paraguay se proclamó como república en 1813, su reconocimiento solo se dio hasta el año 1853 por parte de otros estados. Una segunda etapa estuvo determinada por la definición de sus límites territoriales, los cuales terminaron siendo definidos en conflictos internacionales como la guerra contra la Triple Alianza y la guerra del Chaco. La certeza en los límites territoriales del Paraguay solo se alcanza en el año 1938. Finalmente, hay una tercera etapa en la cual Paraguay hace esfuerzos por el reconocimiento de recursos naturales del mar compartidos, dada su condición de país sin litoral, haciendo esfuerzos en diferentes foros multilaterales. El Embajador Scavone pasó a explicar cómo la historia de Paraguay y Colombia es una historia de coincidencias, y cómo el episodio de la guerra contra la Triple Alianza significó un momento importante de acercamiento entre ambos países debido a las expresiones de solidaridad de Colombia con el Paraguay, como los argumentos señalando que este conflicto era contrario a los principios de derecho internacional como la no intervención, la autodeterminación de los pueblos y el respeto a las normas internacionales. -

Oportunidades Comerciales

ASOCIACIÓN LATINOAMERICANA DE 4 ALADI: PUERTA DE ENTRADA DE LOS PRODUCTOS INTEGRACIÓN PARAGUAYOS AL MERCADO CHILENO La Asociación Latinoamericana de Integración es un En el marco de la ALADI, la relación comercial entre organismo intergubernamental compuesto por doce países: Paraguay y Chile está regida, fundamentalmente por el Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Acuerdo de Complementación Económica Nº 35. Este México,Paraguay,Perú,UruguayyVenezuela. acuerdo permite que los productos paraguayos puedan ingresar al mercado chileno en condiciones SISTEMADE APOYOALOS PMDER preferenciales. Mediante este sistema se financian proyectos de INTERCAMBIOCOMERCIALENTREPARAGUAY Y cooperación de los países de menor desarrollo económico CHILE relativo, Bolivia, Ecuador y Paraguay, bajo la modalidad de estudios,asistenciatécnica,ycapacitación. El comercio entre Paraguay y Chile ha mostrado un crecimiento muy importante de las exportaciones SERVICIOSDE APOYOAL EMPRESARIO paraguayas ha partir del año 2004. En el año 2008 las exportaciones paraguayas hacia Chile fueron de US$ 369 La Secretaría General de la ALADI brinda distintos servicios. millones mientras que, las importaciones paraguayas Ingresandoalsitioweb institucionalpodráinformarsesobre: provenientes desde Chile alcanzaron los US$ 106 millones, con lo cual el superávit comercial ascendió a US$ 263 Acceder a la normativa vigente en materia de comercio millones. exterior, preferencias otorgadas y recibidas, zonas francas, Paraguay guíasde importaciónyexportación. En 2008,