THE DELAWARE WOOLEN INDUSTRY by George H. Gibson June, 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outline Descendant Report for Robert Marvel Planter

Outline Descendant Report for Robert Marvel Planter 1 Robert Marvel Planter b: 15 May 1737 in Stepney Parish, Somerset County, Maryland, d: 25 Jul 1775 in Dover, Kent County, Delaware, USA + Rachel Chase b: 1737 in Worcester County, Maryland, m: 1757 in Somerset, Maryland, d: 27 Aug 1791 in Sussex County, Delaware; Buried in St. John's Episcopal Cemetery ...2 Ann Marvel b: 1753 in Worcester County, Maryland, d: 1807 in Sussex County, Delaware + Charlton Smith b: 18 Oct 1733 in Worcester County, Maryland, m: 01 Jan 1775 in Sussex County, Delaware; Alt Date 27 Mar 1772, d: 1804 in Sussex County, Delaware ......3 Bathsheba Smith b: 1768 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware + Eli Carpenter Sr. b: 1760, m: 05 Oct 1786 in Lewes, Sussex County, Delaware; Lewes and Coolspring Presbyterian Church .........4 Eli Carpenter Jr. b: 10 Jan 1805 in Delaware, d: 09 Nov 1872 in Indiana .........4 Levi Carpenter b: Abt. 1807 ......3 Sally Smith b: 1770 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware, d: Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware ......3 Marvel Smith b: 1772 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1830 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware ......3 Nancy Smith b: 1774 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1836 in Nanticoke Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware + Elisha E. Evans b: 28 Apr 1777 in Blackwater, Sussex Cty, Delaware, m: 02 Sep 1792 in New Castle, Delaware, d: 29 Sep 1836 in Sussex County, Delaware .........4 Betsy Evans b: 1792 .........4 Elizabeth Massy Evans b: 03 Nov 1792 in Georgetown, Sussex County, Delaware, d: 26 Dec 1873 in Georgetown, Sussex County, Delaware + David Maxwell Greenly b: 1790 in Dover, Kent County, Delaware, m: Dec 1814 in Milford, Kent County, Delaware, d: 22 Aug 1873 in Georgetown, Sussex County, Delaware ............5 Elisha Evans Greenly b: 01 Dec 1814 in Georgetown, Sussex County, Delaware, d: 13 Aug 1876 in Smyrna, Kent, Delaware ............5 John Purden Greenly b: 19 Sep 1817 in Georgetown, Sussex County, Delaware, d: Bef. -

2012 Spring Newsletter

The Sheep Geek’s Gazette April 2012 Nottingham and District Guild of Spinners, Weavers and Dyers. Ethnic garments Black and white Bogolanfini (mud cloth) Date: 1970Courtesy of Judy Edmister This three-piece man’s outfit is traditional for the Mali of Western Africa. The upper body cover is left open on the side in traditional African style to facilitate ventilation. The wrapped lower body covering is made of seven strips of hand woven cloth woven by men on a double heddle loom. The skullcap is traditional in design and form. The production of mud cloth starts with plain white cotton cloth strip-woven by men. The narrow strips are then sewn together. The fabric is then soaked in mordant-bearing mulch leaves. The mordant (tannin) soaks into the fabric that takes on an even yellow color. The mud dye process is complex and time consuming. After fermenting the dye in a covered pot for about a year to turn the dye black, iron oxide in the mud reacts with the tannic acid from the mulchtoproduce a colorfast dye. The resulting pattern is painted around the light colored or white design motif. Don’t try this at home. Sheep droppings boiled in milk were once recommended in Ireland as a cure for whooping cough. The Story of the Golden Fleece In Greek mythology, the golden fleece was the fleece of the gold-haired winged ram. It appears in the story of Jason and the Argonauts when Jason has to find the fleece and prove his claim to the throne of Iolcus. -

The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog: the Greenbank Mill and the Philips

0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog Celebrating The History and Historical Sites of Mill Creek Hundred, in the Heart Of New Castle County, Delaware Home Index of Topics Map of Historic Sites Cemetery Pictures MCH History Forum Nostalgia Forum About Wednesday, February 20, 2013 The Greenbank Mill and the Philips House -- Part 1 The power of the many streams and creeks of Mill Creek Hundred has been harnessed for almost 340 years now, as the water flows from the Piedmont down to the sea. There have been literally dozens of sites throughout the hundred where waterwheels once turned, but today only one Greenbank Mill in the 1960's, before the fire Mill Creek Hundred 1868 remains. Nestled on the west bank of Red Clay Creek, the Search This Blog Greenbank Mill stands as a living testament to the nearly three and a half century tradition of water-powered milling in MCH. The millseat at Search Greenbank is special to the story of MCH for several reasons -- it was one of the first harnessed here, it's the longest-serving, and it's the only one still in operable condition. The fact that it now serves as a teaching tool Show Your Appreciation for the MCHHB With PDFmyURL anyone can convert entire websites to PDF! only makes it more special, at least in my eyes. The early history of the millseat at Greenbank is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside....Ok, it's not quite that bad, but the actual facts are far Recent Comments from clear. -

All Hands Are Enjoined to Spin : Textile Production in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts." (1996)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1996 All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth- century Massachusetts. Susan M. Ouellette University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Ouellette, Susan M., "All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth-century Massachusetts." (1996). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1224. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1224 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST c c: 315DLDb0133T[] i !3 ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 1996 History ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Approved as to style and content by: So Barry/ J . Levy^/ Chair c konJL WI_ Xa LaaAj Gerald McFarland, Member Neal Salisbury, Member Patricia Warner, Member Bruce Laurie, Department Head History (^Copyright by Susan Poland Ouellette 1996 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS FEBRUARY 1996 SUSAN M. OUELLETTE, B.A., STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PLATTSBURGH M.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Ph.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Professor Barry J. -

![Delaware Republican (Wilmington, Del.), 1866-02-26, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1878/delaware-republican-wilmington-del-1866-02-26-p-231878.webp)

Delaware Republican (Wilmington, Del.), 1866-02-26, [P ]

W * A\ An Old Resident Gone.—'Thomas Darlington i Fitu Begj.—Thorn was a groat display of ! BDSIEBM. PBBOOEAL lWTSLLinBEOB. *0.— Proposed Ordinance.—'The following ordl- LIST OP LETTER*. gelai« Republican. Cap*. J. M. Barr of Middletown, offers for died at hia residence In Birmingham Township, j boot In oar market laat Saturday. Tho «tails nance wm offered at the meeting oftheOoun- "LETTERS REMAINING UNCLAIMED in tk* fo*t PROFESSIONAL. sale rent his steam saw mill, planing mill, Cheater County, Pa., on the.i7th inat., aged ( were handaomely decorated, and the beauti- ell the loth met, and it wi 1 Jouh lese pass Omese» wiUbington, But* cf D»u«ir«, 2Uk day of Feb- Farmers, Attention! and peach haakst manufactory at Smyrna sta 82 year«. He lived and died near the apot fnl roaata and eteake, tastefully arranged, unless there should be objections presented U. where he waa born. He waa a brother ot that ! were snffieient to tempt the appetite of both A. I D.. MONDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1866. tion, cm the Dslaware Hal*road. agaiust it. A Lore Wm HOMQEPATHIC PHYSICIAN, Lewis 8mUk has sold his mill and about four eminent botanist, Dr. Wm. Darlington, late of rloh and poor. The prices ranged from 20 to An Ordinance to amend the ordinance Aydelott Miss Lee Susanna HARNESS CHEAD aores of ground, situated on BeaverCreek, in West Chester. When a boy it waa his let to 84 cents, which the consamera thought high titled,“Ac Ordinance for regulating the dis Anderson Martha LambFrt Susan (Ut* of WMliiBgten, D. C.,) Tib New Water ©rbibabcb —The propo Brandywine Hdi, to a man named Dilworth of carry hla brother’s weekly washing to this enoagh, althongh the Tenders considered it OflBe« 808 eicpipy Street. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

Sussex County

501 ALLOWANCES AND APPROPRIATIONS. Dolls. Ct,. Amount brought forward, 3,3137 58 To Lowder T. Layton, for damages on new road, 15 00 Albert Webster, do do 05 Appropriation for opening and making said road, 20 00 William K. Lockwood, commissioner on road, 2 days, 2 00 Albert Webster, do 3 3 00 T. L. Davis, do 3 3 00 George Jones, do 2 2 00 William Nickerson, do 2 2 00 Alexander Johnson, surveyor, 7 00 John Cox, for damages on road, 50 00 William Slay, do 06 David Marvel, do 06 Martha Day, do 06 Appropriation to open and make said road, 150 00 $3,642 31 March Session. Thomas S. Buckmaster, for overwork under a resolu- tion, 3 89 Isaac L. Crouch, for work on jail, 87 Joshua Nickerson, for work on a bridge, 2 08 S. C. Leatherberry, cryer of the courts, 20 62 Joab Fox, for work on a bridge, 9 87 James Jones, assessor for Duck Creek hundred, 29 38 Nathan Soward, Little Creek " 25 56 William Slaughter, Dover, " 27 56 John Sherwood, Murderkill, " 34 02 John Quillen, Milford, " 26 46 Henry W. Harrington, Mispillion, " 27 00 Dr. Isaac Jump, for medicine for prisoners in jail, 4 50 William Hirons, commissioner on road, 1 00 Thomas Stevenson, justice peace, for fees, 15 35 Alexander J. Taylor, late sheriff, board of prisoners and fees, 352 51 James B. Richardson, coroner, for fees, 17 23 John P. Coombe, justice of the peace, for fees, I 00 George Smith, commissioner oo new road, 1 00 Joho Ha wk ins, for excess of tax, for the years 1848-9, 12 98 John Sherwood, for services dividing school districts, I 00 Am,unt carried forward, $4,356 19 502 ALLOWANCES AND APPROPRIATIONS. -

A Manual of Electricity, Magnetism, and Meteorology

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES | 34.33 ||||| O691091 – !! !! !! !! ! 2 _- - * - _º º 4.WN iſ A. N. U A ſ, _-_ — of -- … – ( Z.Z.º. cºlºſ Cſºlº, Ayſal & AyA.T.ſ. 5 ºf – ~ - an or sº w - -- > __ anº's ( // E *ſ'. E. O.A.: O I, O & Y. - - º Az _º_*zº, _{Z ~4–. _4% • *. %2. zz & C//4///:3' W. W.4/, /ſ/.../º, SºCſ. ET4/ºr 7, 17//, //, //7/2/, //, 5, , , ,77. //, /wo ºrºzzes *A ºl. II. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- - Tonoon: . * ~ * - - - - - - - - - - - ------ - -> --> * > *.*.*.*, *, * * x - M.A is . .” - P. i. i* - lº Hº -- - - - - - - -- - - - - * ~ * - - - - 2. - THE NEW YORK PUBLIC UIBRARY Astor, ‘f Nox TIL CEN FOUND A TY ONº. *- **º----- ADVERTISEMENT, IN presenting this volume to the public, it is only just to the publishers for me to state, that the long interval which has elapsed between the appearance of the first and the second volumes has arisen from causes over which they had no control. Circum stances having rendered it necessary for them to seek assistance to complete the volume, I was in duced, at their request, to undertake it: and all that Dr. Lardner had contributed was forthwith placed in my hands. It is unnecessary for me to state the difficulties which an author must encounter in attempting to complete a work commenced by another. I must, however, mention that, after a careful examination of the materials placed at my disposal, I have en deavoured to carry out Dr. -

Glossary of Terms

The Missing Chapter: Untold Stories of the African American Presence in the Mid-Hudson Valley Glossary of Terms Bay: A compartment in a barn, used fore storing hay or grain. Britches or Breeches: Short trousers, especially fastened below the knee. Breeches were originally made of leather, but were made of various materials. Buckskin: Leather made from a buck’s skin, could also refer to a thick smooth cotton or woolen cloth. Coating: A cloth used for making coats. Drab coloured: A dull brownish yellow or dull gray color. Felt: A fabric made of wool and hair. Fife: A small high-pitched flute without keys, often used in military and marching bands. Fustian: A coarse sturdy cloth of a cotton-linen blend; any durable fabric with a raised nap made mainly from cotton, for example, corduroy or moleskin. Gaol: is an early Modern English spelling for jail, with the same pronunciation and meaning of a place of legal detention. Grogram: A rough fabric of silk and wool with a diagonal weave. High Dutch: An eighteenth century term for German. Homespun: Spun or woven in the home; a plain coarse woolen cloth made of homespun yarn. Instant (inst.): The current calendar month. Inventory: a detailed list of things in one’s view or possession; especially, a regular survey of all goods and materials in stock. Linsey Woolsey: A coarse fabric of cotton or linen woven with wool. Low Dutch: used to signify those persons of Netherlandish descent. Manchester velvet: A fine cotton used in making dresses. The Missing Chapter: Untold Stories of the African American Presence in the Mid-Hudson Valley Nanekeen: A sturdy yellow or buff cotton cloth. -

Mayor V. Fairfield Improvement Company

Mayor v. Fairfield Improvement Company: The Public’s Apprehension to Accept Nineteenth Century Medical Advancements Ryan Wiggins Daniella Einik Baltimore Environmental History December 21, 2009 I. INTRODUCTION On November 20, 1895, Alcaeus Hooper stood before a crowd of politicians, family, friends, and supporters in Baltimore’s city hall. “We feel that the election just held is more than an unusual one,” Hooper bellowed, “[t]hat it has amounted to a revolution, and it demands a change in the personnel of the many offices under the control of the municipality. The revolution calls louder, however, for a change in the methods of administration.”1 Hooper was about to be inaugurated as Baltimore’s first Republican mayor in a generation. He was a reform candidate who had united Independent Democrats, Republicans, and the Reform League against Isaac Freeman Rasin’s Democratic political machine. Political bosses had dominated Baltimore and Maryland politics since the 1870s, acting as middlemen between the city’s powerful business tycoons and a governmental structure that they largely controlled. In 1895, reform won overwhelmingly at the state and city level.2 Many people were eager for a change they could believe in. In spite of initial gains, including election reform and moves towards greater municipal efficiency, optimism for progressive change in the Hooper administration quickly cooled amongst the Baltimore elite. Hooper refused to acknowledge patronage issues, and in spite of some public support, had considerable trouble with the city council.3 In early 1897, a dispute over the school board set Hooper and the city council against each other in the Maryland Court of Appeals. -

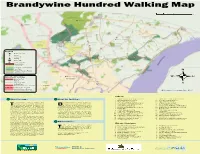

About the Facilities… About the Map… Find out More…

Brandywine Hundred Walking Map ◘Ramsey’s Farm Market ◘Highland Orchard & Market Legend Points of Interest School Historic Site T Parking Park & Ride ◘ Farmers Market Historic District Golf Course New Castle County Parkland State Park Woodlawn Trustees Property Shopping Center Little Italy Farmers Market Bike/Ped Facilities ◘ Hiking/Park Trail Sidewalk ◘Wilmington Farmers Market Planned Sidewalk Camp Fresh On Road Route ◘ Farmers Market Multi-Use Paved Trail or Bike Path ELSMERE Proposed Trail Connection Northern Delaware Greenway Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway © Delaware Greenways, Inc., 2009 About the map… About the facilities… 1 DARLEY ROAD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 17 CARRCROFT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 2 SPRINGER MIDDLE SCHOOL 18 A I DUPONT HIGH SCHOOL 3 TALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 19 SALESIANUM SCHOOL he Brandywine Hundred Walking Map randywine Hundred contains a fairly dense 4 MT PLEASANT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 20 ST EDMONDS ACADEMY illustrates some of the many opportunities network of sidewalks and connections. 5 CLAYMONT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 21 MT PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL for walking and bicycling throughout and In addition, many neighborhood streets T B 6 CHARLES BUSH SCHOOL 22 WILMINGTON FRIENDS UPPER SCHOOL around Brandywine Hundred. In addition, the and regional roads are suitable for walking and map highlights some of the area’s numerous bicycling, particularly those with wide shoulders. 7 LANCASHIRE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 23 BRANDYWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL recreational, cultural, and historical resources. However, not all sidewalks, connections, or road 8 TOWER HILL 24 HOLY ROSARY It is our hope that this map will assist you routes are indicated. 9 HANBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 25 CONCORD HIGH SCHOOL in finding local connections to these nearby This allows you to navigate off landmarks 10 CONCORD CHRISTIAN ACADEMY 26 ST HELENAS destinations and inspire you to enjoy the many and highlighted routes identified on the map. -

Table of Contents TOWN, COUNTY, and STATE OFFICIALS

The Town of Bellefonte Comprehensive Plan 2019 Table of Contents TOWN, COUNTY, AND STATE OFFICIALS ............................................................................................................ 5 Town of Bellefonte ..................................................................................................................... 5 New Castle County ..................................................................................................................... 5 State of Delaware ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 The Authority to Plan .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Community Profile ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Overview ................................................................................................................................... 10 Location ...................................................................................................................................