Unit 4 Norms and Conformity: Asch's Line of Length

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tol, Xeer, and Somalinimo: Recognizing Somali And

Tol , Xeer , and Somalinimo : Recognizing Somali and Mushunguli Refugees as Agents in the Integration Process A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Vinodh Kutty IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David M. Lipset July 2010 © Vinodh Kutty 2010 Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed without the help of many individuals. And to all of them, I owe a deep debt of gratitude. Funding for this project was provided by two block grants from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota and by two Children and Families Fellowship grants from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. These grants allowed me to travel to the United Kingdom and Kenya to conduct research and observe the trajectory of the refugee resettlement process from refugee camp to processing for immigration and then to resettlement to host country. The members of my dissertation committee, David Lipset, my advisor, Timothy Dunnigan, Frank Miller, and Bruce Downing all provided invaluable support and assistance. Indeed, I sometimes felt that my advisor, David Lipset, would not have been able to write this dissertation without my assistance! Timothy Dunnigan challenged me to honor the Somali community I worked with and for that I am grateful because that made the dissertation so much better. Frank Miller asked very thoughtful questions and always encouraged me and Bruce Downing provided me with detailed feedback to ensure that my writing was clear, succinct and organized. I also have others to thank. To my colleagues at the Office of Multicultural Services at Hennepin County, I want to say “Thank You Very Much!” They all provided me with the inspiration to look at the refugee resettlement process more critically and dared me to suggest ways to improve it. -

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Mobbing, Suppression of Dissent/Discontent, Whistleblowing, and Social Medicine

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2012 Mobbing, suppression of dissent/discontent, whistleblowing, and social medicine Brian Martin University of Wollongong, [email protected] Florencia Pena Sanit Martin University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Brian and Pena Sanit Martin, Florencia, Mobbing, suppression of dissent/discontent, whistleblowing, and social medicine 2012, 205-209. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1569 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] EDITORIAL Mobbing, Suppression of Dissent/Discontent, Whistleblowing, and Social Medicine Brian Martin, Florencia Peña Saint Martin Humans can be ruthless in attacking each other – extremely difficult, often with serious health conse- even without any physical violence. Individuals can quences, emotional, physical and mental. Most re- be targets, sometimes inside organizations, some- search on mobbing deals with these sorts of attacks times in domestic or public arenas. In workplaces, within workplaces, but mobbing can also occur in for example, individuals can be singled out for at- other arenas. Some researchers call this “workplace tack because they are different or because they are a bullying”: this is like bullying between children, threat to or unwanted by those with power. Those except it involves adults. However, “bullying” often who are attacked often suffer enormously, with se- implies that one person, the bully, is harassing an- vere effects on their health and well-being. -

Socially Mediated Visibility: Friendship and Dissent in Authoritarian Azerbaijan

International Journal of Communication 12(2018), 1310–1331 1932–8036/20180005 Socially Mediated Visibility: Friendship and Dissent in Authoritarian Azerbaijan KATY E. PEARCE1 University of Washington, USA JESSICA VITAK University of Maryland, USA KRISTEN BARTA University of Washington, USA Socially mediated visibility refers to technical features of social media platforms and the strategic actions of individuals or groups to manage the content and associations visible on social media channels, as well as inferences and consequences resulting from that visibility. As a root affordance, the visibility of content and associations shared in mediated settings can vary, with users typically retaining only partial control over visibility. Understanding how social and technical factors affect visibility plays a critical role in managing one’s online self-presentation. This qualitative study of young dissident Azerbaijanis (N = 29) considers the management strategies as well as the risks and benefits associated with increased visibility when sharing marginalized political views through social media. Socially mediated visibility helps dissidents advocate and connect with like-minded others, but also increases the likelihood that their dissent is visible to those who may disagree with it and can punish them for it. This study considers the effect of the visibility of dissent on peer relationships. Keywords: visibility, Azerbaijan, social media, dissident, affordances, authoritarianism Social media afford users opportunities to broadcast information to small and large audiences, find information, and connect and interact with others who have shared interests. Social media activity is simultaneously mass and interpersonal—or “masspersonal communication” (O’Sullivan & Carr, 2017)— Katy E. Pearce: [email protected] Jessica Vitak: [email protected] Kristen Barta: [email protected] Date submitted: 2017‒02‒08 1 The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their feedback. -

A Moral Right to Dissent? the Case of Civil Disobedience

A MORAL RIGHT TO DISSENT? THE CASE OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree ?W\L -02T5 Master of Arts in Philosophy By Juan Sebastian Ospina San Francisco, California May 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read A Moral Right to Dissent? The case of civil disobedience by Juan Sebastian Ospina, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Philosophy at San Francisco State University. Kevin Toh, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Philosophy Department Shelley Wilcox, Ph.D. Professor, Assistant Chair, Philosophy Department A MORAL RIGHT TO DISSENT? THE CASE OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE Juan Sebastian Ospina San Francisco, California May 2016 Joseph Raz has argued that in liberal states there is no moral right to disobedience. Raz claims that all states ought to be what he calls “liberal states,” which do not require a moral right to civil disobedience. Broadly, my focus in this paper is on describing how civil disobedience can be understood as a moral right to be included in the framework of political rights recognized in liberal states. I try to demonstrate that Raz’s argument proceeds from a limited understanding of political rights and political actions, and suggest that his conclusion is invalid or extremely exaggerated. I advance a tentative argument about the importance of this moral right to the political process of deliberative democracies, and of its inclusion in limited form among political participation rights. -

Psychotherapy in Dissent Some of the Objections to the Rise and Rise of CBT Are Not Based on Fact

DavidVealeFINAL.qxd 31/1/08 1:16 pm Page 1 Psychotherapy in dissent Some of the objections to the rise and rise of CBT are not based on fact. Equally, CBT itself is changing in line with research that advances our understanding of what needs to be integrated within its approach by David Veale I have borrowed the title of defence of the profession Access to Psychological ‘There should be greater this article from the book when it was under heavy Therapies programme (IAPT) patient choice between Psychiatry in Dissent criticism, and argued which has been vilified in different types of therapies published in 1976 by passionately for an evidence- some quarters. I have tried to offered in the NHS’ Professor Anthony Clare, who based approach. I write in a extract the common themes The National Institute for sadly died last year. The book similar vein to correct some of from the various articles and Health and Clinical was very influential in the myths and letters that have been Excellence (NICE) is helping me to decide to train misunderstandings about published in therapy today responsible for guiding the as a psychiatrist. In it, cognitive-behavioural therapy and in the media, and NHS. Its remit is to Professor Clare came to the (CBT) and the Increasing respond. recommend treatments that 4 therapy today February 2008 DavidVealeFINAL.qxd 31/1/08 1:16 pm Page 2 are cost effective and the process and quality of life practitioners so that they therapy for severe minimise the burden for the for the many people with can collect and evaluate depression1,2. -

What Is Mobbing? Budget Cuts Are Not the Only Way Workers Are Forced from Jobs: Workplace Abuse

What is Mobbing? Budget Cuts Are Not the Only Way Workers Are Forced from Jobs: Workplace Abuse “The mobbing syndrome is a malicious attempt to force a person out of the workplace through unjustified accusations, humiliation, general harassment, emotional abuse, and/or terror. “It is a ‘ganging up’ by the leader(s) - organization, superior, co-worker, or subordinate - who rallies others into systematic and frequent ‘mob-like’ behavior. “Because the organization ignores, condones, or even instigates the behavior, it can be said that the victim, seemingly helpless against the powerful and many, is indeed ‘mobbed.’ The result is always injury - physical or mental distress or illness and social misery and, most often, expulsion from the workplace.” -Mobbing: Emotional Abuse in the American Workplace, by Davenport, Schwartz, and Elliott, 1999. When a budget crisis hits a large institution, certain workers often seem to be treated as though they are“expendable,” and are often the first forced out. But this is not the only manner in which workers are driven out of the workplace. Mobbing has been recognized for many years in Europe, and it is also beginning to be identified as a serious workplace problem in the United States. The authors above go on to say, “Mobbing is an emotional assault. Through innuendo, rumors, and public discrediting, a hostile environment is created in which one individual gathers others to willingly, or unwillingly participate in continuous malevolent actions to force a person out of the workplace.” “These actions escalate into abusive and terrorizing behavior. The victim feels increasingly helpless when the organization does not put a stop to the behavior or may even plan or condone it.. -

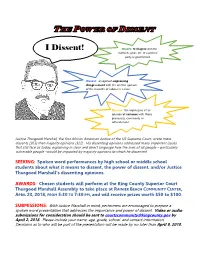

I Dissent! Dissent: to Disagree with the Methods, Goals, Etc

I Dissent! Dissent: to disagree with the methods, goals, etc. of a political party or government. Dissent: an opinion expressing disagreement with the written opinion of the majority of judges in a case. Dissent: to disagree with the methods, goals, etc. of a politicalDissent: the expression of an opinion at variance with those party or governmentpreviously, commonly or officially held. Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Justice of the US Supreme Court, wrote more dissents (363) than majority opinions (322). His dissenting opinions addressed many important issues that still face us today, explaining in clear and direct language how the lives of all people – particularly vulnerable people –would be impacted by majority opinions to which he dissented. SEEKING: Spoken word performances by high school or middle school students about what it means to dissent, the power of dissent, and/or Justice Thurgood Marshall’s dissenting opinions. AWARDS: Chosen students will perform at the King County Superior Court Thurgood Marshall Assembly to take place at RAINIER BEACH COMMUNITY CENTER, APRIL 23, 2018, FROM 5:30 TO 7:30 PM, and will receive prizes worth $50 to $100. SUBMISSIONS: With Justice Marshall in mind, performers are encouraged to prepare a spoken word presentation that addresses the importance and power of dissent. Video or audio submissions for consideration should be sent to [email protected] by April 2, 2018. Please include your name, age, grade, school, and contact information. Decisions as to who will be part of the presentation will be made by no later than April 9, 2018. Submission Information: This information is provided to assist with submissions for participation in the King County Superior Court’s Justice Thurgood Marshall Assembly on April 23, 2018 at the Rainier Beach Community Center from 5:30 to 7:30 PM. -

Portrait of the Activist As a Yes Man: Examining Culture Jamming and Its Actors Through the Circuit of Culture Derrick Shannon

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Portrait of the Activist as a Yes Man: Examining Culture Jamming and Its Actors Through the Circuit of Culture Derrick Shannon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION A PORTRAIT OF THE ACTIVIST AS A YES MAN: EXAMINING CULTURE JAMMING AND ITS ACTORS THROUGH THE CIRCUIT OF CULTURE By DERRICK SHANNON A Thesis submitted to the School of Communication and Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Derrick Shannon on April 01, 2011. ______________________________ Andrew Opel Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Donna Marie Nudd Committee Member ______________________________ Jennifer Proffitt Committee Member Approved: _______________________________________ Steve McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication _______________________________________ Larry Dennis, Dean, College of Communication The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For Dad iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to primarily thank Dr. Andy Opel, Dr. Bill Lawson, and my father Sam Shannon for supporting me through this project, and for pushing me to finish. Without their encouragement and generosity I would not have been able to see this to an end. I would also like to thank Dr. Nudd and Dr. Proffitt for taking part in this and lending their time. Finally, I would like to thank my mother, Ginger Shannon, who is the kindest most inspiring person I know. -

The Politics of Dissent: How Living Within the Truth Threatens Autocracy and Catalyzes Democratic Progress

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The Politics of Dissent: How Living Within the Truth Threatens Autocracy and Catalyzes Democratic Progress Carter A. Hanson Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Hanson, Carter A., "The Politics of Dissent: How Living Within the Truth Threatens Autocracy and Catalyzes Democratic Progress" (2020). Student Publications. 892. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/892 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/892 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politics of Dissent: How Living Within the Truth Threatens Autocracy and Catalyzes Democratic Progress Abstract This article examines Václav Havel’s The Power of the Powerless in the context of a broader ideation of dissent, primarily using Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism and William Connolly’s The Fragility of Things as supplements. Havel’s argument remains relevant over thirty years after its initial publication, and his ideas regarding dissent as a fundamental challenge to authoritarian untruth are valuable and deserve further exploration. From this conceptualization, a “politics of dissent” is proposed as a means to express dissatisfaction with authoritarian government and to reevaluate democratic social and political discourse. -

Contentious Politics, Culture Jamming, and Radical

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation David Matthew Iles, III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Iles, III, David Matthew, "Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 878. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/878 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOXING WITH SHADOWS: CONTENTIOUS POLITICS, CULTURE JAMMING, AND RADICAL CREATIVITY IN TACTICAL INNOVATION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Political Science by David Matthew Iles, III B.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2006 May, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was completed with the approval and encouragement of my committee members: Dr. Xi Chen, Dr. William Clark, and Dr. Cecil Eubanks. Along with Dr. Wonik Kim, they provided me with valuable critical reflection whenever the benign clouds of exhaustion and confidence threatened. I would also like to thank my friends Nathan Price, Caroline Payne, Omar Khalid, Tao Dumas, Jeremiah Russell, Natasha Bingham, Shaun King, and Ellen Burke for both their professional and personal support, criticism, and impatience throughout this process. -

DSM-5 and Personality Disorders: Where Did Axis II Go?

SPECIAL SECTION DSM-5 and Personality Disorders: Where Did Axis II Go? Robert L. Trestman, PhD, MD The past decade has seen a period of extensive research into the etiology, pathophysiology, assessment, and treatment of personality disorders. Concomitantly, a group of experts in the field were brought together to form the Personality and Personality Disorder Work Group for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), charged with the responsibility of updating the diagnostic approach to personality disorders. This article is a review of some of the history of the American Psychiatry Association’s approach to the recognition and diagnosis of personality disorders over the past half century, the process of developing the recommendations for a DSM-5 personality disorder diagnosis and the elimination of the multiaxial system, and how DSM-5 has left us with essentially no changes of relevance to the practice of forensic psychiatry in the process for diagnosing personality disorders or in the specific diagnoses of personality disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 42:141–5, 2014 Many psychiatrists who practice at the interface with no meaningful changes in the clinical diagnosis of the law recognize that there is an apparent over- personality disorder in DSM-5. The story behind representation of people with personality disorders this outcome is enlightening, as it reflects the evolu- (PDs) in civil and criminal cases and in correctional tion of our understanding of personality disorders. settings. The data show