On Removing a Label

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

Ncea Results and Scholarship: How Secondary Schools Fared

NCEA RESULTS AND SCHOLARSHIP: HOW SECONDARY SCHOOLS FARED The first column lists the number of pupils The next three columns give the pass rate achieved the qualification in previous years. achieved. Scholarship is an exam designed roll size or roll changes throughout the year, on the roll at July 1, 2007, to give an indica- at each level of NCEA as a percentage of They can be compared to the national aver- to test the brightest pupils. It is a monetary and the socio-economic background of pu- tion of the size of the school. This needs students in year 11, 12 and 13 respectively. age at the top of the table. The next column award and is separate to NCEA. This table is pils. It might be useful to look at schools of to be considered when comparing results. These figures include pupils who have shows how many Scholarships pupils a snapshot. Pass rates can be influenced by the same decile when making comparisons. School and (decile) Roll Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Schol School and (decile) Roll Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Schol School and (decile) Roll Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Schol % % % No % % % No % % % No NATIONAL 62.8 65.8 54.6 NATIONAL 62.8 65.8 54.6 NATIONAL 62.8 65.8 54.6 CENTRAL NORTH ISLAND Hato Paora College (3) 199 76.8 89.5 73.3 1 Tararua College (4) 419 58.7 70.1 54 0 Forest View High School (3) 631 50 60.5 34.4 1 Horowhenua College (3) 711 47.8 71.4 44.3 4 Wairarapa College (6) 1134 57.6 76.1 66.4 4 Mangakino Area School (1) 42 14.3 40 0 0 Longburn Adventist College (6) 232 90 94.9 89.4 4 Rangitahi College (3) 91 22.7 0 0 0 Mana Tamariki -

HOW to GET to SCHOOL OR COLLEGE on the Gobay Public Transport Network

HOW TO GET TO SCHOOL OR COLLEGE on the goBay Public Transport Network NAPIER SCHOOLS / COLLEGES TAMATEA HIGH SCHOOL IF YOU LIVE IN: BUS ROUTE NO: TIME: ARRIVE: TIME: Bay View 15 7:15am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am Westshore 15 7:25am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am Ahuriri 15 7:35am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am FROM HERE YOU CAN TRANSFER TO THE ROUTE 12 BUS BELOW, FREE OF CHARGE Napier (Dalton Street) 12 8:00am Before Anderson Park 8:08am Marewa 12 8:04am Before Anderson Park 8:08am 1 HOW TO GET TO SCHOOL OR COLLEGE on the goBay Public Transport Network NAPIER SCHOOLS / COLLEGES TARADALE HIGH SCHOOL IF YOU LIVE IN: BUS ROUTE NO: TIME: ARRIVE: Time: Bay View 15 7:15am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am Westshore 15 7:25am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am Ahuriri 15 7:35am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am FROM HERE YOU CAN TRANSFER TO THE ROUTE 12 BUS BELOW, FREE OF CHARGE Napier (Dalton Street) 12 8:00am Taradale 8:20am Marewa 12 8:04am Taradale 8:20am Greenmeadows 12 8:10am Taradale 8:20am IF YOU LIVE IN: BUS ROUTE NO: TIME: ARRIVE: Time: Hastings (Library) 12 7:40am Taradale 8:12am 2 HOW TO GET TO SCHOOL OR COLLEGE on the goBay Public Transport Network NAPIER SCHOOLS / COLLEGES NAPIER GIRLS’ HIGH SCHOOL / SACRED HEART IF YOU LIVE IN: BUS ROUTE NO: TIME: ARRIVE: TIME: Bay View 15 7:15am Shakespeare Road 7:40am Westshore 15 7:25am Shakespeare Road 7:40am Ahuriri 15 7:35am Shakespeare Road 7:40am IF YOU LIVE IN: BUS ROUTE NO: TIME: ARRIVE: TIME: Hastings (Library) 12 7:00am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:55am Taradale 12 7:30am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:55am Greenmeadows 12 7:36am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:55am Pirimai / Onekawa 12 7:40am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:55am Marewa 12 7:46am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:55am Tamatea 13 7:35am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:50am Maraenui or Onekawa 14 7:00am Napier (Dalton Street) 7:30am FROM HERE YOU CAN WALK TO SCHOOL (APPROX. -

Getting to School on Gobay

HOW TO GET TO SCHOOL OR COLLEGE Direct services on the goBay network HBHS TO FLAXMERE (BUS 1) HASTINGS BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL IF YOU LIVE IN: TIME: Hastings Boys’ High School, Karamu Rd 3:05 FLAXMERE TO HASTINGS BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL (BUS 1) Wilson Road 3:15 Dundee Drive 3:16 IF YOU LIVE IN: TIME: Wilson Road, opposite Hugh Little Park 3:17 Wilson Road 7:40 Peterhead Avenue 3:18 Dundee Drive 7:41 Opposite Police Station, Swansea Road 3:20 Wilson Road, opposite Hugh Little Park 7:42 Flaxmere College, Henderson Road 3:21 Peterhead Avenue 7:43 Flaxmere Avenue 3:22 Opposite Police Station, Swansea Road 7:44 Chatham Road 3:28 Flaxmere College, Henderson Road 7:45 Caernarvon Drive 3:29 Flaxmere Avenue 7:46 Opposite BP Station, Flaxmere Village 3:30 36 Ramsey Crescent 7:48 Flaxmere College, Henderson Road 3:32 24 Bangor Street 7:49 Henderson Road 3:33 Kingsley Drive 7:50 Folkestone Road 3:34 Diaz Drive 7:51 Ramsey Crescent 3:24 Hastings Boys’ High School, Karamu Rd 8:20 Kingsley Drive 3:25 Diaz Drive 3:26 Opposite Four Square, Scott Drive 3:28 1 HOW TO GET TO SCHOOL OR COLLEGE Direct services on the goBay network HBHS TO FLAXMERE (BUS 2) HASTINGS BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL IF YOU LIVE IN: TIME: Hastings Boys’ High School, Karamu Rd 3:15 FLAXMERE TO HASTINGS BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL (BUS 2) Wilson Road 3:25 Dundee Drive 3:26 IF YOU LIVE IN: TIME: Wilson Road, opposite Hugh Little Park 3:27 Opposite Four Square, Scott Drive 8:05 Peterhead Avenue 3:28 Chatham Road 8:08 Opposite Police Station, Swansea Road 3:29 Caernarvon Drive 8:10 Flaxmere College, Henderson Road 3:30 -

Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 EIT Mission Statement EIT’s Mission is to provide high quality, relevant and accessible tertiary education for the well-being of diverse communities. EIT Vision Educate. Innovate. Transform. Cover photo supplied by Kirsten Simcox EASTERN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 1 EIT Highlights Rt Hon John Key, Prime Minister, officially opened EIT’s $8.5 million trades and technology complex on 13 August 2010. ITP Quality Review report published in September EIT achieved “highly confident” in educational performance and “confident” in the Institute’s self- assessment capability. Excellence ranking achieved in External Review for educational performance in wide ranging areas such as nursing, foundation education, business, computing, applied social sciences, fashion design, and research. Hon Steven Joyce, Minister of Tertiary Education, approved the merger of EIT Hawke’s Bay with Taira-whiti Polytechnic on 1 December 2010, effective on 1 January 2011. Government approved the establishment of a Hawke’s Bay Trades Academy based at EIT from 2012, one of eleven academies nationwide, from 113 applicants. A new Strategic Plan for 2010-2014 was approved and published. 6% growth in equivalent full-time students (3,298 EFTS) Higher education delivery remained important with degree level activity the single highest area of programme enrolments representing 35% of all EFTS. There was a 41% increase in the number of year 13 students entering degree programmes. Overall 61% of all EFTS studied were at level 5 and above. 100% of EFTS achieved. Youth Guarantee programme targeting school leavers who are not in training or education was fully subscribed, with strong educational outcomes. -

New Zealand Gazette 3997

25 OCTOBER NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 3997 Dated at Wellington this 19th day of October 1990. 5. The powers of the Hawke's Bay Polytechnic Council shall PHIL GOFF, Minister of Education. not be affected by vacancy in the membership thereof. 9011762 First Schedule The Professional Bodies as referred to in subclause 3 (g) to the Hawke's Bay Polytechnic Notice 1990 notice are as follows: Pursuant to section 168 of the Education Amendment Act Hawke's Bay Branch, New Zealand Society of Accountants 1990, the Minister of Education gives the following notice. The Hawke's Bay District Law Society Notice The New Zealand Institute of Management, Hawke's Bay Division (Inc) 1. (a) This notice may be cited as the Hawke's Bay Polytechnic Hawke's Bay Division, New Zealand Dental Association Notice 1990. Medical Association of New Zealand, Hawke's Bay Division (b) This notice shall come into force on the date of its Hawke's Bay Branch, New Zealand Institute of Surveyors publication in the Gazette. The Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand (Inc) 2. There shall be a Council to be known as the Hawke's Bay (Hawke's Bay Branch) Polytechnic Council which shall control the Hawke's Bay Hawke's Bay Branch of Quantity Surveyors Institute of New Polytechnic. Zealand (Inc) New Zealand Institute of Architects, Hawke's Bay Branch 3. The Hawke' s Bay Polytechnic Council shall be constituted Hawke's Bay Branch Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand as follows: New Zealand Nurses' Association (Inc) Napier Branch and (a) Four members appointed by the Minister of Education. -

School Number (Moe)

School Roll Count Regional Council (MoE (MoE) Name School Type Authority Intiative Number (Nov 15) Data) 1606 ACG New Zealand International College Secondary (Year 9-15) 872 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus UFB 2085 ACG Parnell College Composite (Year 1-15) 797 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus UFB 1605 ACG Senior College Secondary (Year 9-15) 242 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus UFB 441 ACG Strathallan Composite (Year 1-15) 912 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus RBI 571 ACG Sunderland Composite (Year 1-15) 316 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus UFB 1200 Ahuroa School Full Primary (Year 1-8) 77 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus RBI 6948 Albany Junior High School Secondary (Year 7-10) 1146 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 1202 Albany School Contributing (Year 1-6) 670 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 563 Albany Senior High School Secondary (Year 11-15) 731 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 6929 Alfriston College Secondary (Year 9-15) 1332 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 1203 Alfriston School Full Primary (Year 1-8) 333 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus RBI 544 Al-Madinah School Composite (Year 1-15) 528 State: Integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 462 Ambury Park Centre for Riding Therapy Secondary (Year 9-15) 50 Private: Fully Reg. Auckland Region Chorus UFB 1204 Anchorage Park School Contributing (Year 1-6) 157 State: Not integrated Auckland Region Chorus UFB 96 Aorere College Secondary (Year 9-15) 1467 State: -

Tairawhiti | Hawke's

TAIRAWHITI | HAWKE’S BAY Events that connect Schools, Communities & Employers APRIL TERM 1 MAY/JUNE/ TERM 2/ AUGUST/ TBC JULY TERM 3 OCTOBER Wairoa College Taradale High School Lytton High School Gisborne Boys’ High Hastings Christian Building and Construc- Friday 3 April 2020 Term 1 Friday 15 May 2020 School College tion Industry Students attending: 300 Students Attending: 800 Students attending: 100 Term 2 Thursday 27 August Security Organisation Students attending: 60 Students attending: 100 TBC Career Force Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o New Zealand Technology Hawkes’s Bay Youth Day Events Te Waiu o Ngati Porou & Industry Association Flaxmere College New ZealandCollege April Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o May Term 2 Security Careers Expo Primary Industry Capabil- Students attending: 250 Gisborne Kawakawa Mai Tawhiti Hawke’s Bay October ity Alliance Term 1 Gisborne Teacher’s Day Out Group Event Includes: Napier Girls’ High School TBC Career Force NZ MAC ITO - Te Kura Kaupapa Māori O Industry Association Term 3 Hawke’s Bay Youth Day Events Te Waiu o Ngati Porou Students attending: 200 April - Te Kura Kaupapa Māori O May Napier Kawakawa Mai Tawhiti Hawke’s Bay Campion College Turanganui a Kiwa TBC Activity Centre (6125) Students attending: 150 Tamatea High School Group Event Includes: MITO Youth Day Events Monday 15 June Term 3 - Campion College Bus Tours Students attending: 120 Students attending: 25 - Gisborne Girls’ High April Te Aute College Students attending: 130 Gisborne Term 1 Connexis Industry Train- Central Hawke’s Bay Students attending: 80 ing Organisation College Tolaga Bay Area School Girls with Hi Vis Events Term 3 TBC MITO Youth Day Events Students attending: 300 Students attending: 40 Bus Tours June April Tuai Napier William Colenso College July Students attending: 425 Industry Training Organisation Consortium Speed Meets July Hawke’s Bay All information is correct at the time of publication. -

Extra Staffing by School Under MAC 23 Calculation for Curriculum Staffing (Based on 2011 Confirmed Year 9-13 Roll)

Extra staffing by school under MAC 23 calculation for curriculum staffing (based on 2011 confirmed year 9-13 roll). School Name FTTE School Name FTTE School Name FTTE School Name FTTE added added added added Albany Junior High School 5.7 Catholic Cathedral College 0 Glendowie College 2.9 James Cook High School 9.5 Albany Senior High School 1.1 Central Hawkes Bay College 0.1 Glenfield College 1.1 James Hargest College 7.5 Alfriston College 8.6 Central Southland College 0 Golden Bay High School 0 John McGlashan College 0 Aorere College 8.9 Chanel College 0 Gore High School 0.6 John Paul College 2.1 Aotea College 3.6 Christchurch Boys' High School 6.7 Green Bay High School 6.7 John Paul II High School 0 Aparima College 0 Christchurch Girls' High School 4.5 Greymouth High School 1.1 Kaiapoi High School 0.4 Aquinas College 0 Craighead Diocesan School 0 Hagley Community College 0 Kaikorai Valley College 0 Aranui High School 0 Cromwell College 0 Hamilton Boys' High School 15.1 Kaikoura High School 0 Ashburton College 6.8 Cullinane College 0 Hamilton Girls' High School 9.6 Kaipara College 0.4 Auckland Girls' Grammar School 7.7 Dannevirke High School 0 Hamilton's Fraser High School 10.7 Kaitaia College 3.2 Auckland Grammar 17.3 Darfield High School 0 Hastings Boys' High School 1.4 Kamo High School 5.8 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist H S 0 Dargaville High School 0 Hastings Girls' High School 2.9 Kapiti College 4.5 Aurora College 0 De La Salle College 1.8 Hato Paora College 0 Karamu High School 2.9 Avondale College 18.7 Dunstan High School 0 Hato -

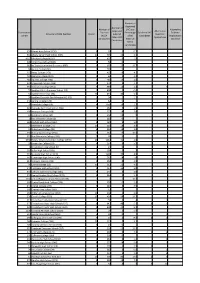

Examination Centre School and MOE Number Decile Number of External

Number of Approved Number of Number of SAC as a Alternative Approved Alternative Examination External Percentage Declined SAC Evidence School and MOE Number Decile External Evidence Centre NCEA of All Candidates Applications NCEA SAC Applications Candidates External Declined Candidates NCEA Candidates 350 Akaroa Area School (350) 8 30 2 6.7 563 Albany Senior High School (563) 10 745 23 3.1 6929 Alfriston College (6929) 3 699 9 1.3 308 Amuri Area School (308) 8 50 0 683 Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery (683) 6 197 25 12.7 96 Aorere College (96) 2 799 0 253 Aotea College (253) 5 463 19 4.1 409 Aparima College (409) 5 62 2 3.2 482 Aquinas College (482) 9 485 14 2.9 323 Aranui High School (323) 2 173 3 1.7 351 Ashburton College (351) 7 589 14 2.4 3 53 Auckland Girls' Grammar School (53) 5 838 5 0.6 54 Auckland Grammar (54) 10 813 43 5.3 93 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist H S (93) 2 94 1 1.1 548 Aurora College (548) 2 82 0 78 Avondale College (78) 4 1365 16 1.2 324 Avonside Girls' High School (324) 6 458 7 1.5 198 Awatapu College (198) 5 357 14 3.9 61 Baradene College (61) 9 456 23 5 8 Bay of Islands College (8) 1 189 0 382 Bayfield High School (382) 8 289 8 2.8 77 Bethlehem College (77) 10 525 18 3.4 31 Birkenhead College (31) 6 361 14 3.9 256 Bishop Viard College (256) 2 162 17 10.5 391 Blue Mountain College (391) 7 69 0 6930 Botany Downs Secondary College (6930) 10 1114 31 2.8 20 Bream Bay College (20) 4 154 8 5.2 6 Broadwood Area School (6) 1 14 0 301 Buller High School (301) 3 168 5 3 319 Burnside High School (319) 8 1428 70 4.9 142 Cambridge -

2015 SAC Application Data from NZQA -‐ by DECILE

2015 SAC Application Data from NZQA - BY DECILE School Low no. of School Decile Total External Applications Percentage SAC Approved School Declined Approval Applications Approved By Disability Category Applications Declined By Disability Category Alternative Evidence Applications Approved By Code applns Candidates Candidates Students Evidence Rate Disability Category between 1 and 4 Sensory Medical Physical Learning Sensory Medical Physical Learning Sensory Medical Physical Learning 4 Whangaroa College 1 66 64 6 Y Broadwood Area School - Manganuiowae 1 50 28 9 Y Northland College 1 185 130 10 Te Kura Taumata o Panguru 1 15 11 11 Opononi Area School 1 35 32 57 Tamaki College 1 331 295 58 Y Tangaroa College 1 546 383 88 Otahuhu College 1 681 600 9 1.3% 9 4 100.0% 90 Y McAuley High School 1 425 414 91 Mangere College 1 426 333 5 1.2% 5 3 100.0% 93 Y Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist High School 1 99 92 94 De La Salle College 1 434 391 19 4.4% 12 7 7 63.2% 97 Y Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Senior School 1 421 187 99 Manurewa High School 1 1,084 929 35 3.2% 33 11 2 94.3% 100 James Cook High School 1 785 417 16 2.0% 15 15 1 93.8% 101 Papakura High School 1 371 228 8 2.2% 7 3 1 87.5% 104 Wesley College 1 211 203 16 7.6% 13 16 3 81.3% 119 Y Huntly College 1 185 92 134 Flaxmere College 1 227 76 147 Te Whanau-a-Apanui Area School 1 34 12 185 Patea Area School 1 37 24 206 Ngata Memorial College 1 50 41 212 Tolaga Bay Area School 1 59 45 214 Y Wairoa College 1 217 133 255 Porirua College 1 307 266 12 3.9% 9 12 3 75.0% 256 Bishop Viard College 1 173