The Fate of Caroline Broun; Wife of Peter Nicholas Broun, the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caroline Broun the Wife of Peter Nicholas Broun, First Colonial Secretary of the Swan River Colony

VOL. 13 NO. 11 SEPTEMBER 2017 Caroline Widowed, Exiled, Broun Shipwrecked, 1804-1881 Rescued, Destitute, Stranded. The Fate of the Widow of WA’s First Colonial Secretary See page 328 WHO WAS DAISY’S DAD? PART 3 AUSTRALIANS DECORATED IN SERBIA WAGS AWARDS The story concludes... The search for Descendants Three new Life Members Page 332 Page 336 Page 318 FEATURE: WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORY The Fate of Caroline Broun The wife of Peter Nicholas Broun, first Colonial Secretary of the Swan River Colony Robert Atkins, Member 10908 and Don Blue, Member 425. Don and Robert presented the journal editors with a very unusual dilemma prior to the publication of the last issue. They both submitted virtually the same story quite independently. Third cousins, they had not met previously! As it turns out, Don had obtained a photocopy of Caroline Broun’s diary from Robert’s father in the early 1970s. The diary is now in Robert’s possession having inherited his father’s papers and documents. This diary contains Caroline Broun’s writings, copies of letters, records of family events and newspaper cuttings, which appears to have commenced after she returned to England in 1849. Caroline Broun (1804 – 1881) is Don’s 3 times great grandmother and Robert’s 2 times great grandmother. We start with her account of the sinking of the Hindoo. It tells something of her character. The Shipwreck On 9 September 1848 “Mrs. P. Broun” was aboard the Hindoo bound for London from Fremantle. Caroline Broun was the only woman on board and she wrote the following (probably to her 1 son James), reported in the Inquirer 18 July 1849 : “Jan. -

50 More Western Australian Historical Facts Trivia

50 More Western Australian Historical Facts & Trivia v Prepared for Celebrate WA by Ruth Marchant James v Q1. Thirty-one year old Peter Broun, his wife Caroline and their two young children arrived on the Parmelia in 1829. What was Broun’s position in the new Swan River Colony? A. Colonial Secretary Q2. What important historic event was celebrated between December 1996 and February 1997? A. The tri-centenary of de Vlamingh’s visit Q3. During the Second World War Mrs Chester, the eccentric widow of a former Subiaco mayor, purchased two spitfires and one training plane for the RAAF at a cost of 8000 and 1000 pounds respectively. For years she was a common sight in the city and most people identified her by what nick-name? A. ‘Birds’ Nest’ Q4. What nationality was the early Benedictine Monk Rosendo Salvado who, together with fellow monks, founded the settlement of new Norcia? A. Spanish Q5. The Benedictine Monks came from Spain to establish an Aboriginal mission. In what year did they establish the settlement of New Norcia? A. 1846 (New Norcia celebrated its 150th year in 1996.) Q6. In what area of the Wheatbelt was the earliest inland European settlement in Western Australia? A. The Avon Valley Q7. By 8 June 1829 three ships were anchored in Cockburn sound. Name them. A. HMS Challenger, Parmelia and HMS Sulphur Q8 The sinking of HMAS Sydney in November 1941 posed a mystery for many years. What was the name of the German merchant raider involved? (Updated as at September 2010.) A. The Kormoran Q9. -

Annual Report 2017-2018

Annual Report 2017-2018 Office of the Auditor General – Annual Report 2017-18 01 About our report Welcome to our 2017-18 Annual Report. We hope you find this report valuable in understanding our performance and the services we delivered during the year to inform Parliament on THE PRESIDENT THE SPEAKER public sector accountability and performance. LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY You can access this and earlier annual reports on our website at www.audit.wa.gov.au. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR We have structured this report around the 4 result areas of THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2018 our Strategic Plan – Our People, Our Tools, Our Approach and Our Products. It also describes our functions and In accordance with section 63, as modified by Schedule 3, of the Financial operations, and presents the audited financial statements and Management Act 2006, I hereby submit to Parliament for its information key performance indicators for the year ended 30 June 2018. the Annual Report of the Office of the Auditor General for the year ended 30 June 2018. Our front cover prominently displays Western Australia. The introduction of local government auditing in October 2017 The Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions (page 12), has significantly broadened our role in auditing the of the Financial Management Act 2006 and the Auditor General Act 2006. state public sector for the benefit of Western Australians. This year, more than any other year, we have travelled the state to explore and implement our new mandate. CAROLINE SPENCER AUDITOR GENERAL 20 September 2018 Feedback National Relay Service TTY: 13 36 77 (to assist people with hearing and voice impairment). -

2021 Yearbook to All Swimmers

GOOD LUCK 2021 YEARBOOK TO ALL SWIMMERS. WE’LL BE WAITING FOR YOU AT THE SOUTH32 RECOVERY ZONE. www.south32.net 32ND PARALLEL 32ND [Lavan ad] Only 19.7 km to go Contents President’s Message ............................................. 3 Sponsorship Information ....................................... 4 Records ................................................................ 5 2021 Champions of the Channel .......................... 6-7 2021 Rottnest Channel Solo Swimmers ............... 9-10 Participant Story - Stephanie Rowton .................. 11 Participant Story - Dean Kern ............................... 13 Participant Story - Mike and Shaun Oostryck ....... 14 2021 Rottnest Channel Duo Swimmers ................ 15-16 2021 Rottnest Channel Skippers ........................... 18-19 Ferry Timetable ..................................................... 20 Pre-Event Information Skipper Information ............................................... 22 Swimmer Safety ................................................... 23 Managing the Fleet ................................................ 24 Is your boat ready to go ........................................ 25 Paddler Information............................................... 26 The Serious Stuff The Start ................................................................ 2A The Channel ........................................................... 3A The Finish Channel and Finish Line ....................... 4A-5A Course Map ........................................................... 6A-7A PULL -

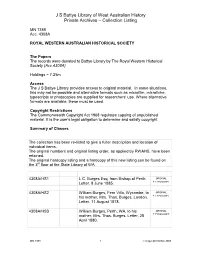

JS Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing MN 1388 Acc. 4308A ROYAL WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Papers The records were donated to Battye Library by The Royal Western Historical Society (Acc.4308A) Holdings = 7.25m Access The J S Battye Library provides access to original material. In some situations, this may not be possible and alternative formats such as microfilm, microfiche, typescripts or photocopies are supplied for researchers’ use. Where alternative formats are available, these must be used. Copyright Restrictions The Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 regulates copying of unpublished material. It is the user’s legal obligation to determine and satisfy copyright. Summary of Classes The collection has been re-listed to give a fuller description and location of individual items. The original numbers and original listing order, as applied by RWAHS, have been retained. The original hardcopy listing and a hardcopy of this new listing can be found on the 3rd floor at the State Library of WA 4308A/HS1 L.C. Burges Esq. from Bishop of Perth. ORIGINAL Letter, 8 June 1885. + TYPESCRIPT 4308A/HS2 William Burges, Fern Villa, Wycombe, to ORIGINAL his mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges, London. + TYPESCRIPT Letter, 11 August 1878. 4308A/HS3 William Burges, Perth, WA, to his ORIGINAL mother, Mrs. Thos. Burges. Letter, 28 + TYPESCRIPT April 1880. MN 1388 1 Copyright SLWA 2008 J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing 4308A/HS4 Tom (Burges) from Wm. Burges, ORIGINAL Liverpool, before sailing for Buenos + TYPESCRIPT Ayres. Letter, 9 June 1865. 4308A/HS5 Richard Burges, Esq. -

Western Australia a History from Its Discovery to the Inauguration of the Commonwealth

WESTERN AUSTRALIA A HISTORY FROM ITS DISCOVERY TO THE INAUGURATION OF THE COMMONWEALTH BY J.S. BATTYE, LITT.D. PUBLIC LIBRARIAN OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1924. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, EDINBURGH, GLASGOW, COPENHAGEN, NEW YORK, TORONTO, MELBOURNE, CAPE TOWN, BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, MADRAS, SHANGHAI. HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY. PREFACE. In view of the prominent part taken by Australia in the recent war, and the enthusiasm which the achievements of the Australian Forces have aroused throughout the Empire, the story of one of the great States of the Australian Commonwealth may not be without some general interest. The work has been the result of over twenty years' research, undertaken, in the first instance, in conjunction with the Registrar-General (Mr. M.A.C. Fraser) and his Deputy (Mr. W. Siebenhaar) for the purpose of checking the historical introduction to the Year Book of Western Australia. It has since been continued in the hope that it may prove a contribution of more or less value to the history of colonial development. In the prosecution of the work, the files of the Public Record Office, London, were searched, and copies made of all documents that could be found which related to the establishment and early years of the colony. These copies are now in the possession of the Public Library of Western Australia, which contains also most of the published matter in the way of books and pamphlets dealing with the colony, as well as almost complete files of the local newspapers to date, and the original records of the Colonial Secretary's Office up to 1876. -

Aboriginal History Journal

Aboriginal History Volume Fifteen 1991 ABORIGINAL HISTORY INCORPORATED The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), May McKenzie (Secretary/Publicity Officer), Robin Bancroft, Valerie Chapman, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Jonas, Harold Koch, C.C. Macknight, Isabel McBryde, John Mulvaney, Isobel White, Judith Wilson, Elspeth Young. ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1991 Editors: Luise Hercus, Elspeth Young. Review Editor: Isobel White. CORRESPONDENTS Jeremy Beckett, Ann Curthoys, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, will be welcomed. Future issues will include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, r6sum6s of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material in the journal. Views and opinions expressed by the authors of signed articles and reviews are not necessarily shared by Board members. The editors invite contributions for consideration; reviews will be commissioned by the review editor. Contributions and correspondence should be sent to: The Editors, Aboriginal History, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, GPO Box 4, Canberra, ACT 2601. Subscriptions and related inquiries should be sent to BIBLIOTECH, GPO Box 4, Canberra, ACT 2601. -

![2019 YEARBOOK Rottnest Channel Swim Saturday 23 February 2019 [Lavan Ad] Only 19.67 Km to Go](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2892/2019-yearbook-rottnest-channel-swim-saturday-23-february-2019-lavan-ad-only-19-67-km-to-go-3672892.webp)

2019 YEARBOOK Rottnest Channel Swim Saturday 23 February 2019 [Lavan Ad] Only 19.67 Km to Go

2019 YEARBOOK Rottnest Channel Swim Saturday 23 February 2019 [Lavan ad] Only 19.67 km to go Lavan is proud to be a sponsor of the Rottnest Channel Swim lavan.com.au Photo: Peta North PF 35213 Lavan Rottnest Channel Swim.indd 1 18/11/17 11:26 am Only 19.67 km to go Contents President’s Message ........................................... 3 Facts and Figures ............................................... 5 2019 Champions of the Channel .....................6-7 Participant Story - Barbara Pellick ..................... 9 2019 Rottnest Channel Solo Swimmers ......10-11 Participant Story - Lisa Romeo ......................... 12 Participant Story - Luke and Michael ................ 14 2019 Rottnest Channel Duo Swimmers .......15-16 2019 Rottnest Channel Skippers ..................18-19 Ferry Timetable ................................................. 20 Pre-Event Information Skipper Information ........................................... 22 Swimmer Safety ............................................... 23 Fremantle Volunteer Sea Rescue Group ........... 24 Is your boat ready to go .................................... 25 Paddler Information........................................... 22 The Serious Stuff The Start ............................................................ 2A The Channel ....................................................... 3A The Finish Channel and Finish Line ..............4A-5A Course Map ..................................................6A-7A PULL OUT AND Support Boat Information .................................. 8A TAKE -

WESTRALIAN SCOTS: Scottish Settlement and Identity in Western Australia, Arrivals 1829-1850

WESTRALIAN SCOTS: Scottish Settlement and Identity in Western Australia, arrivals 1829-1850 Leigh S. L. Beaton, B.A (Honours) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2004 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary institution. …………………………. (Leigh Beaton) i THESIS ABSTRACT Before the end of 1850, Scottish settlers in Western Australia represented a small minority group of what was, in terms of the European population, a predominantly English colony. By comparison to the eastern Australian colonies, Western Australia attracted the least number of Scottish migrants. This thesis aims to broaden the historiography of Scottish settlement in Australia in the nineteenth century by providing insights into the lives of Westralian Scots. While this thesis broadly documents Scottish settlement, its main focus is Scottish identity. Utilising techniques of nominal record linkage and close socio- biographical scrutiny, this study looks beyond institutional manifestations of Scottish identity to consider the ways in which Scottishness was maintained in everyday lives through work, social and religious practices. This thesis also demonstrates the multi-layered expressions of national identity by recognising Scottish identity in the Australian colonies as both Scottish and British. The duality of a Scottish and British identity made Scots more willing to identify eventually as Westralian -

Documents on Western Australian Education 1830 - 1973

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 1976 Documents on Western Australian education 1830 - 1973 B. T. Haynes (Ed.) Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks Part of the History Commons Haynes, B.T., Barrett, G.E.B., Brennan, A.E., & Brennan, L. (Eds). (1976). Documents on Western Australian education 1830 - 1973. Claremont, Australia: Claremont Teachers College. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this document may contain references to people who have died. This Book is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/6785 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. DOCUMENTS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION 1830-1973 B.T. HAYNES :no .9941 G.E.B. BARRETT DUC A. BRENNAN L. BRENNAN DOCUMENTS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION 1830 - 1973 THEMES FROM WESTERN AUSTRALIAN· HISTORY A Selection of Documents and Readings B.T. -

Membership of the Legislative Council 1832–1870

MEMBERSHIP OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL 1832–1870. Between 1832 and 1867 the membership of the Legislative Council consisted of the Governor and four (five from 1847) official nominee members who were also members of the Executive Council. From 1839 there were also four non-official nominee members, increasing to six in 1867. The lists that follow do not take account of a number of short-term official nominee members in an acting capacity. GOVERNOR Captain James Stirling, 1832–1839 Administrator/Lt Gov Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1832–1833 (Sep) Administrator/Lt Gov Captain Richard Daniell, 1833 (Sep)–1834 (Aug) John Hutt, 1839–1846 Lt Col Andrew KH Clarke, 1846–1847 Administrator Lt Col Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1847–1848 Captain Charles Fitzgerald, 1848–1855 Arthur Edward Kennedy, 1855–1862 John Stephen Hampton, 1862–1868 Administrator Lt Col John Bruce, 1869–1870 Frederick Aloysius Weld, 1870–1875 OFFICIAL NOMINEE MEMBERS Commandant (Commander of the Troops/most senior officer) Captain Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1832–1833 (Sep) Captain Richard Daniell, 1833–1835 (July) (deceased) Captain (later Lt Col) Frederick Chidley Irwin, 1836–1854 Lt Col GM Reeves, 1854–1855 Lt Col John Bruce, 1855–1870 Major Robert Henry Crampton (Acting), 1867 Colonial Secretary Peter Broun (Brown), 1832–1846 George Fletcher Moore (Acting), 1846 (Nov)–1847 (May) Richard Robert Madden, 1847–1849 Revitt Henry Bland, 1849 (Jan)–1850 (Mar) Thomas Newte Yule (Acting), 1850 (Mar–Oct) Alexander John Piesse, 1850 (Nov)–1851 (Mar) Thomas Newte Yule (Acting), 1851 (Mar–Dec) -

P1279b-1291A Hon Sue Ellery

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Tuesday, 27 March 2012] p1279b-1291a Hon Sue Ellery; Hon Alison Xamon; Hon Wendy Duncan; Hon Linda Savage; Hon Helen Bullock; Hon Michael Mischin; Hon Matt Benson-Lidholm; Hon Donna Faragher; Hon Phil Edman; Hon Ed Dermer; Hon Ken Baston; Hon Brian Ellis WESTERN AUSTRALIA DAY (RENAMING) BILL 2011 Second Reading Resumed from 21 March. HON SUE ELLERY (South Metropolitan — Leader of the Opposition) [8.13 pm]: Before I begin my comments on the bill, members will be aware that it was read into the house on the Wednesday of last week. Behind the Chair, the Leader of the House approached the opposition and asked whether we would be prepared to bring on the bill today to assist in finding some work for us to do. The Leader of the House is loath to vary the arrangements whereby a bill sits on the table for a week, and members on this side certainly appreciate that. I want to put on record that normally we would not be dealing with this bill until tomorrow. The bill before us renames what we know now to be Foundation Day to Western Australia Day and amends the acts that refer to public holidays—that is, the Public and Bank Holidays Act 1972 and the Minimum Conditions of Employment Act 1993, which refers to rates of payment and entitlements on public holidays. It is a very small and very simple bill, but, symbolically, it is very important. Foundation Day celebrates the formal beginning of European settlement in Western Australia through the establishment of the Swan River Colony.