Parrots, Pasta and the Politics of Language: Making the Ethical Case for Language Policy in Quebec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montreal: Restaurants and Activities USNCCM14

Montreal: Restaurants and Activities USNCCM14 Montreal, July 17-20, 2017 Restaurants Montreal is home to a wide variety of delicious cuisines, ranging from fine dining foodie delicacies to affordable gems. Below you will find a guide to many of the best restaurants near the Palais des Congrès (PDC). Restaurants were grouped according to price and ordered according to distance from the convention center. Prices shown are the price range of main courses within a restaurant’s menu. Casual Dining Located on the Border of Old Montreal and China Town, there are many casual dining places to be found near the convention center, particularly to the north of it. < 1 km from PDC Mai Xiang Yuan, 1082 Saint-Laurent Boulevard, $10-15, 500 m Made-to-order Chinese dumplings made with fillings such as lamb, curried beef, and pork. Niu Kee, 1163 Clark St., $10-25, 550 m Authentic Chinese Restaurant, specializing in Szechwan Dishes. Relaxed, intimate setting with large portions and a wide variety of Szechwan dishes available. LOV (Local Organic Vegetarian), 464 McGill St., $10-20, 750 m Sleek, inspired vegetarian cuisine ranging from veggie burgers & kimchi fries to gnocchi & smoked beets. Restaurant Boustan, 19 Sainte-Catherine St. West, $5-12, 800 m As the Undisputed king of Montreal food delivery, this Lebanese restaurant offers tasty pita wraps until 4:00 A.M. For delivery, call 514-844-2999. 1 to 2 km from PDC La Pizzaiolle, 600 Marguerite d'Youville St., $10-20, 1.1 km Classic pizzeria specializing in thin-crust, wood-fired pies, and other Italian dishes. -

The Tropical Forest

CREDITS This guide was produced by the Projet manager and supervisor • Manon Curadeau Education and Activities Department, Montreal Biodôme In co-operation with the representatives of the following Literacy Centres: • Carole Doré Centre de lecture et d'écriture • Diane Labelle Lettre en main • Clode Lamare La Jarnigoine and La société des amis du Biodôme Illustrations • Francine Mondor Graphic design and computer graphics • Anthony Cirino and Frida Franco Translation • Terry Knowles and Pamela Ireland Produced with financial assistance from: • Government of Canada Human Resources Development The Montreal Biodôme wishes to thank the members of the above-mentioned literacy groups and the « Le Tour de lire » centre, for their help in evaluatin the project. TABLE OF CONTENTS This guide contains: • an activities reservation form • important information regarding your trip to the Biodôme • pre-visit activities • follow-up activities using the Alpha-Biodôme guides • some other ideas for your group It also comes with: • a videotape; • a colour overhead transparency of the Americas. N. B. Any reproduction of the video or this guide must be authorized by the Education and Activities Department of the Montreal Biodôme. The great majority of trainers at literacy centres are women. At their request, we have used the feminine gender when referring to both men and women representatives in this guide. No discrimination is intended. Thanks! ACTIVITIES RESERVATION FORM HI ! So you’ve reserved for an activity at the Biodôme as part of the « Alpha-Biodôme -

Profile Space for Life: a Place, a Commitment, a Movement Charles

PR OFILE SpaCE FOR LIFE: A PLACE, A COMMITMENT, A MOVEMENT Charles Mathieu Brunelle Space for Life, Montréal, Canada Abstract: The Montréal Space for Life is a C$189 million project that brings the city’s Biodôme, Insectarium, Botanical Garden, and Planetarium together in one place to offer an integrative experience that fosters immersion, connection, and participation; and a public square that creates new means of gathering, inhabiting a space, and building and experiencing everyday life. Canada’s largest natural sciences museum complex is being transformed into the first space dedicated to humankind and nature. Resumo: O Espaço para a Vida, de Montreal, é um projeto no valor de 189 milhões de dólares canadianos que reúne o Biodôme, o Insectarium, o Jardim Botânico e o Planetário da cidade num lugar que oferece uma experiência integradora que fomenta a imersão, a ligação e a participação; e uma praça pública que cria novas formas de reunião, de habitação de um espaço e de construção e experiência da vida quotidiana. O maior complexo museológico de ciências naturais do Canadá está a ser transformado no primeiro espaço dedicado à humanidade e à natureza. Biodiversity refers to all forms of life on Earth. We know that 25% to 50% of all species will disappear by the end of this century. We also know that our survival depends on biodiversity, which provides us with countless services. It feeds us, cares for us, and even determines the quality of the air we breathe. In fact, biodiversity provides us with so many services that it is very difficult to assign it economic value. -

CONSERVING PLANT DIVERSITY: the 2010 Challenge for Canadian Botanical Gardens Compiled and Edited by David A

A Partnership for Plants in Canada CONSERVING PLANT DIVERSITY: The 2010 Challenge for Canadian Botanical Gardens Compiled and edited by David A. Galbraith and Laurel McIvor February 2006 A Partnership for Plants in Canada RECOMMENDED CITATION: Galbraith, D. A. and McIvor, L. (ed.). 2006. Conserving Plant Diversity: the 2010 Challenge for Canadian Botanical Gardens. Investing in Nature: A Partnership for Plants in Canada and Botanic Gardens Conservation International. London. Published by: Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House 199 Kew Road Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW UK Tel.: +44 (0)20 8332 5951 Fax: +44 (0)20 8832 5956 URL: http://www.bgci ISBN 1-905164-06-8 (English Version) ISBN 1-905164-07-6 (Edition Français) © 2006 Botanic Gardens Conservation International In partnership with: The full report is available online at www.bgci.org. Materials may be reproduced with the written permission of BGCI. Environment Environnement Canada Canada Aussi disponable en français. Contents Executive Summary, Acknowledgments . 2 Contributors to the Text, Credits Introduction . 3 What is a Botanical Garden? The International Agenda for Botanic Gardens in Conservation (2000) What is the 2010 Challenge? . 4/5 A Biodiversity Action Plan for Botanic Gardens and Arboreta in Canada (2001) Botanical Gardens and Natural Areas Action Plan Themes and Recommendations: Toward 2010 . 6 Governor’s Garden, Chateau Ramezay Museum Rare and endangered plants initiatives at Les Jardins de Metis / Reford Gardens, Grand-Métis, Québec Theme 1: Conserving Canada’s Natural Plant Diversity . 7 Progress and Successes Recommendations for 2006–2010 . 8 Conserving Endangered Species in Newfoundland Theme 2: Enriching Biodiversity Education . 9 Progress and Successes Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Department of Natural History, Botany and Mycology Recommendations for 2006–2010 . -

A Stay in Montreal Four-Day Itinerary

A STAY IN MONTREAL FOUR-DAY ITINERARY AT THE CENTRE OF A MAJOR AIR, LAND, AND SEA TRANSPORTATION NETWORK, MONTRÉAL IS AN IDEAL ATTRACTION FOR CRUISE SHIPS ALONG THE MAJESTIC ST. LAWRENCE RIVER AND THE NORTH AMERICAN EAST COAST. EVERY YEAR, THE PORT OF MONTREAL WELCOMES THOUSANDS OF CRUISE SHIP PASSENGERS TO ITS IBERVILLE PASSENGER TERMINAL. A CLEAN, SAFE, AND UNIQUE CITY WITH A EUROPEAN CACHET AND A WEALTH OF ATTRACTIONS FOR TOURISTS TO CHOOSE FROM, MONTRÉAL BOASTS FINE RESTAURANTS, ELEGANT BOUTIQUES, DEPARTMENT STORES, SHOPPING COMPLEXES, WELL- PRESERVED HISTORICAL BUILDINGS, MUSEUMS, IMPRESSIVE CONCERT HALLS, AND NUMEROUS THEATRES AND STADIUMS THAT ARE HOME TO PROFESSIONAL SPORTS TEAMS. DAY 1 - OLD MONTRÉAL AND THE QUAYS OF THE OLD PORT The cobblestone streets of Old Montréal have witnessed the passage Museum of Montréal or some of the fine eateries at Place Jacques- of time for more than 360 years. Today, art galleries, artisan Cartier. boutiques, terraces, and cafés conduct business within the walls of You can work off some calories by visiting the Marché Bonsecours, gracious century-old structures, while the Quays of the Old Port are which showcases the creations of Québec artists, designers, and home to a wide array of outdoor activities and services for all tastes. artisans, and by having a look at some of the artisanal boutiques and art galleries on Saint-Paul Street. Your trip on dry land begins with a tour of the Quays. You can either take a refreshing and relaxing stroll along the waterfront or enjoy a For the rest of the afternoon, discover Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal ride on exclusive quadricycles with manual steering and multi-foot Museum of Archaeology, a national historic site rising above the propulsion! Both provide excellent views of the city and some of its actual remains of the city's birthplace. -

Beautiful Gardens That Taste Good, Too

Beautiful gardens that taste good, too Flowers, plants – and bugs – are on the menus at these stunning gardens by Anne Kostalas Canadian gardens are known for their extraordinary beauty, and now you can eat your way through their delights from coast to coast. At Reford Gardens in Québec (also known as Jardins de Métis), flowers and plants grown in the microclimate on the Gaspesie Peninsula, feature in a new range of jams, jellies and pickles. There are pickled daisy and daylily buds, jams scented with lavender and lemon basil and jellies from crabapples, mint and Labrador tea, a wetland plant with strongly flavoured leaves used as a tea by First Nations. Chef Pierre Olivier Ferry at the Estevan Lodge in the grounds of the stunning gardens, uses these ingredients in his menu, which also includes locally sourced sea urchin, halibut and lobster. Other homegrown delights include purple sage butter, strawberry soup and geranium scented tart. Reford Gardens were named after Elsie Reford, a keen gardener and plant collector who summered here from 1926 to 1958. The gardens, symbolized by the Himalayan Blue Poppy that Reford grew so well, are home to more than 3,000 species, cultivars and varieties of plants, both native and exotic. (Open June to September) Butchart Gardens (pronounced butch-art) in Victoria, British Columbia is a National Historic Site of Canada with 55-acres of stunning floral gardens. The tradition of Afternoon Tea is still observed here with its sandwiches, sweet treats and the gardens' own blend of teas. You can take the loose-leaf tea home with you. -

Things to See in Montreal

Things to see in Montreal: Notre-Dame Basilica: https://www.basiliquenotredame.ca/en Montreal Botanical Garden: http://espacepourlavie.ca/en/botanical-garden Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal: https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/ Mount-Royal Park: Within easy walking distance from McGill. The "interactive map" is especially useful: http://www.lemontroyal.qc.ca/en/learn-about-mount-royal/homepage.sn Old Montreal/ Old Port: http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/eng/accueila.htm Montreal Biodome: http://espacepourlavie.ca/en/biodome Saint Laurent Boulevard A commercial and cultural street that runs north to south through the city center Free Montreal Tours and Montreal Food Tours: www.freemontrealtours.com Saint Helen’s Island An island located in the Saint Lawrence river, home to a beautiful park, beach, formula one course, amusement park, casino and wonderful historical buildings. Underground City Montreal has an Underground City, which is a series of interconnected tunnels beneath the city that run for over 32km. The tunnels connect shopping malls, over 2000 stores, 7 metro stations,universities, banks, offices, museums, restaurants. https://montrealundergroundcity.com/ Jean-Talon Market A famous open-air market with speciality vendors selling local produce, meats, cheese,fish and speciality goods. https://www.marchespublics-mtl.com/en/marches/jean-talon-market/ Atwater Market Located beside Canada Parks “Lachine Canal”, the Atwater Market is an open air market that offers local produce, meats, cheese,fish and speciality goods. https://www.marchespublics-mtl.com/en/marches/atwater-market/ Hotels: AirBnb: AirBnB offers you somebody’s home as a place to stay in Montreal. You may choose this option instead of a hotel at your own discretion. -

Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Beyond Eden: Cultivating Spectacle in the Montreal Botanical Garden Ana Armstrong A Thesis in The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magisteriate in Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 1997 O Ann Armstrong, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington ONawaON KlAON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your hle Votre retersnce Our file Narre reterence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Beyond Eden: Cultivating Spectacle in the Montreal Botanical Garden AM Armstrong The Montreal Botanical Garden, a 180-acre complex comprised of over thmy outdoor and ten indoor landscapes located in the city's east-end, is the product of a Depression-era government funded Public Works project. -

MEETING DISCOUNT COUPONS Atitc Vi Ies and Attractions (Approximative VALUE of $450) Meeting

MEETING DISCOUNT COUPONS ATITC VI IES AND ATTRACTIONS (APPROXIMATIVE VALUE OF $450) MEETING To help you make the most of your visit, we’re pleased to offer you these Welcomemoney-saving coupons.to Montréal! To take advantage of a deal, simply show the supplier the printed coupon as well as your passport or convention name badge. While you are here, follow us to stay in the know and live the city like a local. Also, share your wonderful moments on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook Discover Montréal with the #MTLMOMENTS hashtag. on your mobile! Enjoy your stay… à la Montréal ! BLOG buzzmtl.com /montreal @montreal /TourismeMontreal @visit_montreal /visitmontreal tourisme-montreal.org MEETING Atrium 2 for 1 Le 1000 Spectacular indoor rink open all year round! This coupon entitles you to two entry tickets for the price of one. Atrium Le 1000 1000 De La Gauchetière Street West Downtown 514 395-0555 Bonaventure www.le1000.com Schedule: Open all year round. Spring and summer: 11:30 a.m. to 6 p.m.; fall and winter: 11:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Terms and conditions: Cannot be combined with any other offer. No monetary value. Offer valid from January 1 to December 22, 2014. 1 MEETING Brisket Montréal 2 for 1 on poutine, smoked meat & Salon and pig knuckle meat platter after 4 p.m. Krausmann Present this coupon while ordering and receive two ‘BEST OF’ platters for the price of one. The platter includes Québec poutine, authentic smoked meat and marinated pig knuckle meat, served with coleslaw and dill pickle. -

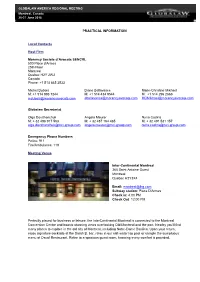

PRACTICAL INFORMATION Local Contacts Host Firm Morency

GLOBALAW AMERICA REGIONAL MEETING Montreal, Canada 25-27 June 2015 PRACTICAL INFORMATION Local Contacts Host Firm Morency Societe d’Avocats SENCRL 500 Place d'Armes 25th Floor Montreal Quebec H2Y 2W2 Canada Phone: +1 514 845 3533 Michel Dubois Diane Bellavance Marie-Christine Mikhael M: +1 514 893 7244 M: +1 514 434 9544 M : +1 514 296 2666 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Globalaw Secretariat Olga Dovzhanchuk Angela Meurer Nuria Codina M: + 32 498 917 563 M: + 32 487 164 485 M: + 32 491 531 157 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Emergency Phone Numbers Police: 911 Fire/Ambulance: 119 Meeting Venue Inter-Continental Montreal 360 Saint Antoine Ouest Montreal Quebec H2Y3X4 Email: [email protected] Subway station: Place D'Armes Check in: 4:00 PM Check Out: 12:00 PM Perfectly placed for business or leisure, the InterContinental Montreal is connected to the Montreal Convention Centre and boasts stunning views overlooking Old Montreal and the port. Nearby you’ll find many places to explore in the old city of Montreal, including Notre-Dame Basilica. Upon your return, enjoy signature cocktails at the Sarah B. bar, relax in our salt-water lap pool or sample the sumptuous menu at Osco! Restaurant. Retire to a spacious guest room, knowing every comfort is provided. GLOBALAW AMERICA REGIONAL MEETING Montreal, Canada 25-27 June 2015 Currency The unit of Canadian currency is Canadian dollars. Its sign is $ and its ISO code is CAD. You can buy Canadian Dollars at foreign exchange banks and other authorized money exchangers. -

Toronto-Niagara Falls

MONTRÉAL 3 DAYS / 2 NIGHTS With its rich history and deep roots in the past, Montréal is a delightful blend of the New World and the Old. Shaped by its history and its culture, the city has a personality all its own. • 2 Nights Hotel Accommodation in greater Montréal • 2 Breakfasts • 2 Dinners (Including an authentic Sugar Shack Feast). • Guided sightseeing city tour of Montréal – Travel in time through Old Montreal’s tales and best kept secrets, from yesteryear to today. Cartier Saint-Paul Streets, Royal Bank Building, City Hall, Notre-Dame Basilica, Champ-de-Mars, St. Joseph’s Oratory, Bonsecours Market and so much more! • Pointe-à-Callière Museum of Archeology – Visit the heart of an authentic archaeological site. The unusual underground route covering six centuries of history, from the times when Natives camped here to the present day, is an emotion-packed look at the very essence of a city born over 375 years ago. • Montréal’s Biodôme – This is an environmental museum like no other in the world, leading students through four of the world’s most beautiful ecosystems of the America’s: the tropical forest; the Laurentian forest; the St. Lawrence marine environment and the Polar World of the Arctic and Antarctic. • Montreal underground shopping – The most famous aspect of shopping in Montreal is the Underground City, directly under the heart of the city, 19 miles long. Constantly growing, the "city" - which links many major buildings and multi-level shopping malls in the area - is a shopper's paradise in any season. • DJ Disco Cruise – Enjoy cruising on the St. -

Best for Kids in Montreal"

"Best for Kids in Montreal" Realizado por : Cityseeker 30 Ubicaciones indicadas Ghosts of Old Montreal "Haunting Visit" If you are looking for something other than the ordinary run-of-the-mill sightseeing tours, then consider the Old Montreal Ghost Trail. A historical mystery tour set in Montreal's French colonial days, the tour includes some of the city's most famous ghosts. Other tours include the New France Ghost Hunt and Montreal's Historical Crime Scenes. Tours are in by David Iliff (Diliff) both English and French. +1 514 868 0303 www.fantommontreal.com [email protected] 469 Rue St-François-Xavier, Montreal QC Le Saint-Sulpice Hotel "Boutique Old Town Stay" Le Saint-Sulpice Hotel is a chic hotel located in Old Montreal. The hotel offers an array of luxurious suites that make it the perfect destination for a romantic getaway or a relaxed family vacation. It's the extra touches like luxury toiletries from French beauty brand L'Occitane en Provence, soft bathrobes, plush bedding and Ipod docks that elevate the experience by KassandraBay here. In-room spa treatments and massages are ideal to unwind after a hectic day. The award-winning restaurant, Sinclaire ensures a great culinary experience for culinary enthusiasts and in-suite fire-side dining is available on request. The family-friendly hotel also offers childcare services on request. For a pampering stay in the heart of the Old Town, Le Saint-Sulpice Hotel is a superb choice. +1 514 288 1000 www.lesaintsulpice.com/ [email protected] 414 rue Saint Sulpice, om Montreal QC Montréal Science Centre "State of the Art" Montréal Science Centre is a science and technology center that has quickly become one of the Old Port's biggest attractions.