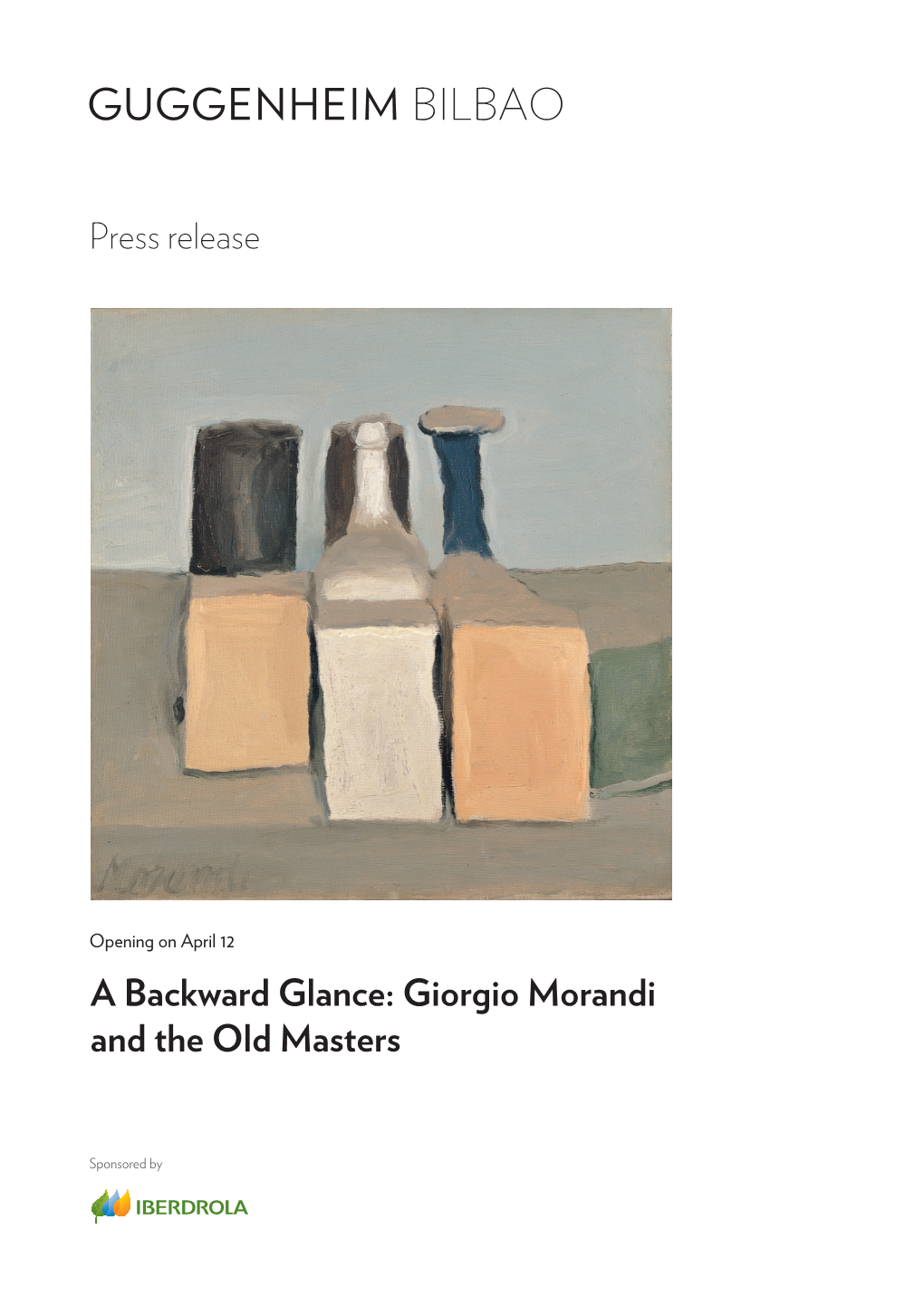

A Backward Glance: Giorgio Morandi and the Old Masters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

Giulio Paolini and Giorgio De Chirico Explored for Cima's

GIULIO PAOLINI AND GIORGIO DE CHIRICO EXPLORED FOR CIMA’S 2016-17 SEASON Dual-focus Exhibition Reveals Unexplored Ties between Artists, Including Metaphysical Masterpieces by de Chirico Not Seen in U.S. in 50 Years, And Installation, Sculpture, and New Series of Works on Paper by Paolini From Left to Right: Giorgio de Chirico, Le Muse Inquietanti, 1918. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Giulio Paolini, Controfigura (critica del punto vista), 1981. © Giulio Paolini. Courtesy of Fondazione Giulio e Anna Paolini. New York, NY (April 5, 2016) – This October, the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA)’s annual installation will take a focused look at the direct ties between two Italian artists born in different centuries but characterized by deep affinities: the founder of Metaphysical painting, Giorgio de Chirico (1888- 1978), and leading conceptual artist Giulio Paolini (b. 1940). With a long-held interest in de Chirico’s oeuvre, Paolini often quotes signature motifs from the earlier artist’s works, despite defying de Chirico’s traditional painterly methods. As evidenced in CIMA’s installation, Paolini has appropriated certain of de Chirico’s meditations on the nature of representation, acknowledging him as a precursor of postmodernism. By juxtaposing important works by both artists in “conversation,” CIMA’s 2016-17 season will present a new appreciation of de Chirico’s metaphysical art and its lasting relevance. On view October 7, 2016 through June 24, 2017, Giorgio de Chirico – Giulio Paolini / Giulio Paolini – Giorgio de Chirico will be the fourth presentation mounted by CIMA, which promotes public appreciation for and new scholarship in 20th-century Italian art through annual installations, public programming, and its fellowship program. -

GIORGIO MORANDI 5 – 26 March 2016 Tuesday to Sunday – 2 Pm to 7Pm Via Serlas 35, CH-75000, St Moritz

GIORGIO MORANDI 5 – 26 March 2016 Tuesday to Sunday – 2 pm to 7pm Via Serlas 35, CH-75000, St Moritz ROBILANT+VOENA are pleased to present an exhibition of paintings by Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) on view at their St Moritz gallery from 5-26 of March 2016. This will be the second exhibition at the gallery dedicated to the celebrated Italian artist, following the 2011 show ‘Still Life’ held at their London space. The exhibition will include works the artist realised during the 1940s and 1960s, bringing together a selection of eight landscapes and still lifes. Morandi was a unique, poetic and challenging artist renowned for his subtle and contemplative paintings which, despite the repetition of subject-matter, are extremely complex in their organisation and execution. Throughout the course of his extensive and very prolific career, Morandi remained committed to developing a deliberately limited visual language. In doing so he concentrated almost exclusively on the production of still lifes and landscapes, repeatedly making use of the same familiar subject-objects: bottles, vases, boxes, flowers or the same landscape views, taken from the window of his home on Via Fondazza or in Grizzana. Included in this exhibition are two Flower paintings produced ten years apart (in 1943 and 1953) and two Still Lifes, from 1949/1950 and 1959. Whilst these paintings are characterised by simplicity of composition, great sensitivity to tone, colour, light and compositional balance, it is possible to notice in his later works a shift in focus, which tends to fade and gradually dissolve the material. In addition, the show will feature four paintings from his Landscape series. -

LCK Notes on Vectors Wang

Notes on Vectors 2. Xin Wang One of those choices, as analyzed and problematized by Lui himself in the 1994 essay, was adopting a “Western art idiom” as an artist from “the East,” subjected as he or she often is to discriminating standards.2 Time and critical discourse have evolved in a way that notions such as the East-West dichotomy have become obscure, yet the reality the crude terminology connotes remains real and present, since abstraction in particular has been established as emblematic of the West’s modernist ambition. In a private seminar titled “Curating Multiple Modernities,” organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in spring 2015, a professor from a distinguished graduate program asked: why did non-Western artists try to catch up with Western modernism? 1. One of his fellow panelists offered a compelling answer: it’s an exercise of artistic freedom In 1993, while pursuing an MFA at the Goldsmiths College in London, Lui Chun Kwong (b. 1956) driven by a sense of ownership rather than the urge to “catch up.” Lui’s own account of his arrived at a curious turn. Having explored painting on a spectrum from lyrical to borderline sabbatical years in New York during the 1980s (where he treated himself as an “outsider and photo-realism in the late 1970s, followed by expressively figural and symbolist experiments observer” as much as an “insider”) testifies as much to this motive.3 Yet he felt the urge, as until the early 1990s, he began working with abstraction defined by a singular process: pouring an artist who grew up in Hong Kong, received initial training in Taiwan, and exposed himself streams of acrylic across painted or untouched canvases before further articulation by brush, to the vibrant art scenes in New York and London, to gain self-clarification, understanding resulting in compositions of infinitesimal striations. -

Index Press Release P. 2 Exhibition Itinerary P. 6

Index Press Release P. 2 Exhibition itinerary P. 6 Autobiography P. 12 Exhibited works P. 14 Lenders P. 29 Info P. 30 Morandi’s places P.31 Educational Department P. 32 MAMbo points out P. 33 1 PRESS RELEASE Giorgio Morandi 1890-1964 curated by Maria Cristina Bandera and Renato Miracco MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna 22nd January - 13 th April 2009 With 107 works coming from the most important collections from all over the world, Bologna celebrates the master with an extraordinary exhibition narrating his artistic itinerary. From 22 January to 13 April 2009 MAMbo – Museo d'Arte Moderna di Bologna houses the long-waited anthological exhibition Giorgio Morandi 1890-1964, cured by Maria Cristina Bandera and Renato Miracco and organised by the Bolognese museum along with the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York where this exhibition was from 16 September to 14 December 2008 and had an extraordinary success of critics and public. Bologna, Morandi’s home town, pays homage to him after less than a century from his pictorial beginnings, with one of the most complete exhibitions ever arranged, which presents 90 oil paintings, 13 watercolours, 2 drawings, and 2 etchings. The public could see the works coming from the biggest Italian and international museums and collections, collected in an exhaustive corpus documenting the path and the expressive evolution from the artist’s beginnings through the metaphysical research up to the fading of the watercolours of the last years, passing through all the techniques he experimented. Thanks to the curators’ choices we can compare, sometimes for the first time, works coming from different sites, connections that highlight analogies in the compositional setting and variations obtained through minimal light modulations, displacements of figures or subtle chromatic and tone changes, thus allowing an emblematic comparison of the research always in becoming, which characterised Morandi’s work. -

On Giorgio Morandi: Milton Glaser in Conversation with Matilde Guidelli-Guidi and Nicola Lucchi

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 On Giorgio Morandi: Milton Glaser in Conversation with Matilde Guidelli-Guidi and Nicola Lucchi ON GIORGIO MORANDI: MILTON GLASER IN CONVERSATION WITH MATILDE GUIDELLI-GUIDI AND NICOLA LUCCHI 0 italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/on-giorgio-morandi-milton-glaser-in- Milton Glaser | Matilde Guidelli-Guidi | Nicola Lucchi Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 ABSTRACT This is the transcript of a wide-ranging interview with artist and graphic designer Milton Glaser that took place at CIMA in 2016. Glaser discusses his experiences as a Fulbright grantee in Bologna, Italy, where he enrolled in an etching class taught by Giorgio Morandi at the city’s Accademia di Belle Arti. The interview provides insights into Morandi’s personality and teaching method, into Glaser’s consideration of Morandi’s oeuvre, and into the designer’s own artistic vision. In 1952, a young Milton Glaser (b. 1929, New York) traveled on a Fulbright Scholarship to Bologna, where he would study with Giorgio Morandi. If this serendipitous encounter resulted from the system of cultural diplomacy put in place in the aftermath of World War II, Italian geography helped, too. Glaser was pursuing a research project that required frequent travel between Venice and Florence. The members of the U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission recommended that Glaser make Bologna his temporary home, as the city constituted a strategic node in the peninsula’s railroad network and residing there would ease Glaser’s commute. Furthermore, they suggested that as a graphic arts student with knowledge of etching, Glaser might find a congenial mentor in Morandi, who had resumed teaching that technique at Bologna’s Accademia di Belle Arti after the war.1 Visiting Italy under the aegis of the Fulbright program in the 1950s was a cultural experience for a new generation of intellectuals as well as a ITALIAN MODERN ART diplomatic mission sui generis. -

Installation of Rarely Seen Work by Italian Modern Master Giorgio Morandi Opens at Cima October 2015

INSTALLATION OF RARELY SEEN WORK BY ITALIAN MODERN MASTER GIORGIO MORANDI OPENS AT CIMA OCTOBER 2015 Showcasing Morandi’s Rare, Early Paintings from 1930s, Installation Marks First Time in Decades That Majority of Works will be on View in the U.S. From Left to Right: Giorgio Morandi, Self-portrait, 1930, and Still Life, 1931. Private collection. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. New York, NY (October 6, 2015) – This October, the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) will present a major installation of Giorgio Morandi’s (1890–1964) rarely seen paintings from the 1930s—a seminal and yet relatively unexplored decade for the acclaimed Italian modernist, during which he reached full artistic maturity and developed his distinct pictorial language. Featuring nearly 40 paintings, etchings, and drawings, the presentation will mark the first time in decades that the majority of these works—gathered from important public and private holdings across Europe—will be on view in the U.S. The installation will also include select works from the very beginning and end of the artist’s career, in the 1910s and 1960s respectively, to demonstrate the thematic continuities in his practice. On view October 9, 2015 through June 25, 2016, Giorgio Morandi will be the third presentation mounted by the nonprofit, which promotes public appreciation of and new scholarship on Italian 20th-century art through its annual installations and research fellowships. In conjunction with the installation, CIMA will present work by four contemporary artists—Tacita Dean, Wolfgang Laib, Joel Meyerowitz, and Matthias Schaller—relating to Morandi’s practice thematically or conceptually. -

Christie's the Eye of the Architect: a Collection

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 30 JANUARY 2018 CHRISTIE’S THE EYE OF THE ARCHITECT: A COLLECTION THAT CAPTURES THE SYNERGY BETWEEN PAINTING AND ARCHITECTURE FRANCIS BACON’S THREE STUDIES FOR A PORTRAIT WILL LEAD THE GROUP FURTHER ARTISTS INCLUDE PABLO PICASSO, GIORGIO DE CHIRICO, FERNAND LÉGER, JOAN MIRÓ AND GIORGIO MORANDI Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Portrait, Oil on canvas, 1976, Estimate: £10,000,000-15,000,000 London – Christie’s will offer The Eye of the Architect, a diverse collection of Modern and Post-War art, during ‘20th Century at Christie’s’, a series of sales that will take place in London from 20 February to 7 March 2018: Impressionist and Modern Art and The Art of the Surreal Evening Sales (both 27 February), Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale (28 February) and Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale (6 March). Focusing primarily on figurative compositions, this tightly curated group of works not only reveals the collector’s discerning eye and architectural mind, but also a passion for artists who continuously sought to push the boundaries of tradition in their art. Including works by some of the most celebrated masters of the twentieth century avant-garde, from Pablo Picasso to Francis Bacon, Giorgio de Chirico to Joan Miró, and Fernand Léger to Giorgio Morandi, this varied group is united in their intimate scale and exploration of similar thematic concerns. The group will be led by Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Portrait (1976, estimate: £10,000,000-15,000,000), the artist’s penultimate ode to his great muse Henrietta Moraes, whose stark depiction of facial features and realist palette reveal the influence of Picasso on Bacon’s work. -

David Zwirner New York, NY 10011 Telephone 212 517 8677

537 West 20th Street Fax 212 517 8959 David Zwirner New York, NY 10011 Telephone 212 517 8677 For immediate release GIORGIO MORANDI November 6 – December 19, 2015 Opening reception: Friday, November 6, 6 – 8 PM Press preview with Laura Mattioli and David Leiber, Director at David Zwirner: 10 AM David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings from the 1940s to the 1960s by the celebrated Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890- 1964) on view at our 537 West 20th Street location in New York. The first major exhibition of Morandi’s later work in America since the acclaimed 2008 retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the show will focus primarily on the period during which he developed and refined his investigations of serial, reductive, and permutational forms and compositions—aspects that had a profound influence on twentieth-century and contemporary art and painting. The exhibition will include important loans from institutions such as the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., as well as from numerous significant private collections. Over the course of his five-decade career, Morandi was most prolific during the postwar years from 1948 until his death in 1964, when he executed more than half of his entire output of paintings. Throughout these intensely Natura morta (Still Life), 1956 creative years, Morandi worked almost exclusively in series. Remaining Oil on canvas dedicated to the repertoire of subjects that had occupied him since the early 11 13 ¾ x 17 /16 inches (35 x 45 cm) Private Collection 1910s, including tabletop still lifes of bottles, boxes, vases, and flowers, as © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), well as occasional landscapes, his variations on a given compositional motif New York / SIAE, Rome became more persistent, nuanced, and abstract in the later part of his life. -

THESIS FINAL DRAFT March 2010

IMPLICATIONS OF STILL LIFE REPRESENTATION OF THE DOMESTIC OBJECT by Renée Lynn Haggart B.A., University of British Columbia, 2007 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES In the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Graduate Liberal Studies © Renée Lynn Haggart 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2010 All rights reserved. However in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada , this work may be reproduced without authorization under the conditions for Fair Dealing . Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Albers and Morandi: Never Finished

Albers and Morandi: Never Finished January 7– April 3, 2021 537 West 20th Street, New York Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta (Still Life), 1953. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say. —Italo Calvino David Zwirner is pleased to present Albers and Morandi: Never Finished, curated by gallery Partner David Leiber. On view at the gallery’s 537 West 20th Street location, the exhibition explores the formal and visual affinities and contrasts between two of the twentieth century’s greatest painters: Josef Albers (1888–1976) and Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964). Both Albers and Morandi are best known for their decades-long elaborations of singular motifs: from 1950 until his death in 1976, Albers employed his nested square format to experiment with endless chromatic combinations and perceptual effects, while Morandi, in his intimate still lifes and occasional landscapes, engaged viewers’ perceptual understanding and memory of everyday objects and spaces. Albers and Morandi: Never Finished will put each artist’s distinctive treatment of color, shape, form, morphology, and seriality in dialogue. Looking specifically at the stunning palettes of Morandi’s celebrated tabletop still lifes depicting humble vessels and vases and Albers’s seminal Homage to the Square series, the exhibition will elucidate how the two artists’ careful daily acts of duration and devotion allowed each to highlight the essence of color and the endless possibilities of their respective visual motifs. This shared aesthetic intensity links both artists and underscores their deep commitment to their forms. As Morandi once said, “One can travel the world and see nothing. -

Morandi, Relationships, Fascism, Still Life

Morandi, Relationships, Fascism, Still Life By William Eaton Zeteo is Looking and Listening, November 2015 This pdf is text only; to see the images visit Zeteo Living with the objects, they became his family, his neighbors, his friends. — Janet Abramowicz, former assistant to Morandi You don’t have to paint a figure to express human feelings. — Robert Motherwell1 (1) For what, in the past year, have been revealed to be psychological reasons, I have long been drawn to the still lifes of the twentieth-century Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, one of the great still-life painters, etchers, and watercolorists. There is a dominant interpretation of Morandi’s work, and the primary purpose of the present set of notes is to bring out of the shadows quite another interpretation. Subsequently and, in a sense, challenging the interpretation I am about to advance, I will discuss Morandi’s connections to Italian fascism and how these connections may lead us to interpret or see the work in yet other ways. There may be those who wish for one of these three interpretations to be the right one. In fact, we are here only scratching the surface; it is easy enough, for example, to see a great deal of Morandi’s paintings—still lifes and landscapes—as being of walls, or of buildings and architecture more generally. As for right or best, I will say, rather, that, 1 Abramowicz made this statement at a discussion at the Center for Italian Modern Art, 7 November 2015. More from this discussion soon to come. I have not been able to track down the source of the Motherwell statement.