Topic 4: Cauchy's Integral Formula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16 Flourishing From the Start: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured? Kristin Anderson Moore, PhD, Child Trends Christina D. Bethell, PhD, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Introduction Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Every parent wants their child to flourish, and every community wants its Public Health children to thrive. It is not sufficient for children to avoid negative outcomes. Rather, from their earliest years, we should foster positive outcomes for David Murphey, PhD, children. Substantial evidence indicates that early investments to foster positive child development can reap large and lasting gains.1 But in order to Child Trends implement and sustain policies and programs that help children flourish, we need to accurately define, measure, and then monitor, “flourishing.”a Miranda Carver Martin, BA, Child Trends By comparing the available child development research literature with the data currently being collected by health researchers and other practitioners, Martha Beltz, BA, we have identified important gaps in our definition of flourishing.2 In formerly of Child Trends particular, the field lacks a set of brief, robust, and culturally sensitive measures of “thriving” constructs critical for young children.3 This is also true for measures of the promotive and protective factors that contribute to thriving. Even when measures do exist, there are serious concerns regarding their validity and utility. We instead recommend these high-priority measures of flourishing -

Integration in the Complex Plane (Zill & Wright Chapter

Integration in the Complex Plane (Zill & Wright Chapter 18) 1016-420-02: Complex Variables∗ Winter 2012-2013 Contents 1 Contour Integrals 2 1.1 Definition and Properties . 2 1.2 Evaluation . 3 1.2.1 Example: R z¯ dz ............................. 3 C1 1.2.2 Example: R z¯ dz ............................. 4 C2 R 2 1.2.3 Example: C z dz ............................. 4 1.3 The ML Limit . 5 1.4 Circulation and Flux . 5 2 The Cauchy-Goursat Theorem 7 2.1 Integral Around a Closed Loop . 7 2.2 Independence of Path for Analytic Functions . 8 2.3 Deformation of Closed Contours . 9 2.4 The Antiderivative . 10 3 Cauchy's Integral Formulas 12 3.1 Cauchy's Integral Formula . 12 3.1.1 Example #1 . 13 3.1.2 Example #2 . 13 3.2 Cauchy's Integral Formula for Derivatives . 14 3.3 Consequences of Cauchy's Integral Formulas . 16 3.3.1 Cauchy's Inequality . 16 3.3.2 Liouville's Theorem . 16 ∗Copyright 2013, John T. Whelan, and all that 1 Tuesday 18 December 2012 1 Contour Integrals 1.1 Definition and Properties Recall the definition of the definite integral Z xF X f(x) dx = lim f(xk) ∆xk (1.1) ∆xk!0 xI k We'd like to define a similar concept, integrating a function f(z) from some point zI to another point zF . The problem is that, since zI and zF are points in the complex plane, there are different ways to get between them, and adding up the value of the function along one path will not give the same result as doing it along another path, even if they have the same endpoints. -

MATH 305 Complex Analysis, Spring 2016 Using Residues to Evaluate Improper Integrals Worksheet for Sections 78 and 79

MATH 305 Complex Analysis, Spring 2016 Using Residues to Evaluate Improper Integrals Worksheet for Sections 78 and 79 One of the interesting applications of Cauchy's Residue Theorem is to find exact values of real improper integrals. The idea is to integrate a complex rational function around a closed contour C that can be arbitrarily large. As the size of the contour becomes infinite, the piece in the complex plane (typically an arc of a circle) contributes 0 to the integral, while the part remaining covers the entire real axis (e.g., an improper integral from −∞ to 1). An Example Let us use residues to derive the formula p Z 1 x2 2 π 4 dx = : (1) 0 x + 1 4 Note the somewhat surprising appearance of π for the value of this integral. z2 First, let f(z) = and let C = L + C be the contour that consists of the line segment L z4 + 1 R R R on the real axis from −R to R, followed by the semi-circle CR of radius R traversed CCW (see figure below). Note that C is a positively oriented, simple, closed contour. We will assume that R > 1. Next, notice that f(z) has two singular points (simple poles) inside C. Call them z0 and z1, as shown in the figure. By Cauchy's Residue Theorem. we have I f(z) dz = 2πi Res f(z) + Res f(z) C z=z0 z=z1 On the other hand, we can parametrize the line segment LR by z = x; −R ≤ x ≤ R, so that I Z R x2 Z z2 f(z) dz = 4 dx + 4 dz; C −R x + 1 CR z + 1 since C = LR + CR. -

1 the Complex Plane

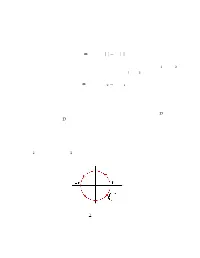

Math 135A, Winter 2012 Complex numbers 1 The complex numbers C are important in just about every branch of mathematics. These notes present some basic facts about them. 1 The Complex Plane A complex number z is given by a pair of real numbers x and y and is written in the form z = x+iy, where i satisfies i2 = −1. The complex numbers may be represented as points in the plane, with the real number 1 represented by the point (1; 0), and the complex number i represented by the point (0; 1). The x-axis is called the \real axis," and the y-axis is called the \imaginary axis." For example, the complex numbers 1, i, 3 + 4i and 3 − 4i are illustrated in Fig 1a. 3 + 4i 6 + 4i 2 + 3i imag i 4 + i 1 real 3 − 4i Fig 1a Fig 1b Complex numbers are added in a natural way: If z1 = x1 + iy1 and z2 = x2 + iy2, then z1 + z2 = (x1 + x2) + i(y1 + y2) (1) It's just vector addition. Fig 1b illustrates the addition (4 + i) + (2 + 3i) = (6 + 4i). Multiplication is given by z1z2 = (x1x2 − y1y2) + i(x1y2 + x2y1) Note that the product behaves exactly like the product of any two algebraic expressions, keeping in mind that i2 = −1. Thus, (2 + i)(−2 + 4i) = 2(−2) + 8i − 2i + 4i2 = −8 + 6i We call x the real part of z and y the imaginary part, and we write x = Re z, y = Im z.(Remember: Im z is a real number.) The term \imaginary" is a historical holdover; it took mathematicians some time to accept the fact that i (for \imaginary," naturally) was a perfectly good mathematical object. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

The Integral Resulting in a Logarithm of a Complex Number Dr. E. Jacobs in first Year Calculus You Learned About the Formula: Z B 1 Dx = Ln |B| − Ln |A| a X

The Integral Resulting in a Logarithm of a Complex Number Dr. E. Jacobs In first year calculus you learned about the formula: Z b 1 dx = ln jbj ¡ ln jaj a x It is natural to want to apply this formula to contour integrals. If z1 and z2 are complex numbers and C is a path connecting z1 to z2, we would expect that: Z 1 dz = log z2 ¡ log z1 C z However, you are about to see that there is an interesting complication when we take the formula for the integral resulting in logarithm and try to extend it to the complex case. First of all, recall that if f(z) is an analytic function on a domain D and C is a closed loop in D then : I f(z) dz = 0 This is referred to as the Cauchy-Integral Theorem. So, for example, if C His a circle of radius r around the origin we may conclude immediately that 2 2 C z dz = 0 because z is an analytic function for all values of z. H If f(z) is not analytic then C f(z) dz is not necessarily zero. Let’s do an 1 explicit calculation for f(z) = z . If we are integrating around a circle C centered at the origin, then any point z on this path may be written as: z = reiθ H 1 iθ Let’s use this to integrate C z dz. If z = re then dz = ireiθ dθ H 1 Now, substitute this into the integral C z dz. -

Math 336 Sample Problems

Math 336 Sample Problems One notebook sized page of notes will be allowed on the test. The test will cover up to section 2.6 in the text. 1. Suppose that v is the harmonic conjugate of u and u is the harmonic conjugate of v. Show that u and v must be constant. ∞ X 2 P∞ n 2. Suppose |an| converges. Prove that f(z) = 0 anz is analytic 0 Z 2π for |z| < 1. Compute lim |f(reit)|2dt. r→1 0 z − a 3. Let a be a complex number and suppose |a| < 1. Let f(z) = . 1 − az Prove the following statments. (a) |f(z)| < 1, if |z| < 1. (b) |f(z)| = 1, if |z| = 1. 2πij 4. Let zj = e n denote the n roots of unity. Let cj = |1 − zj| be the n − 1 chord lengths from 1 to the points zj, j = 1, . .n − 1. Prove n that the product c1 · c2 ··· cn−1 = n. Hint: Consider z − 1. 5. Let f(z) = x + i(x2 − y2). Find the points at which f is complex differentiable. Find the points at which f is complex analytic. 1 6. Find the Laurent series of the function z in the annulus D = {z : 2 < |z − 1| < ∞}. 1 Sample Problems 2 7. Using the calculus of residues, compute Z +∞ dx 4 −∞ 1 + x n p0(z) Y 8. Let f(z) = , where p(z) = (z −z ) and the z are distinct and zp(z) j j j=1 different from 0. Find all the poles of f and compute the residues of f at these poles. -

![B1. the Generating Functional Z[J]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0425/b1-the-generating-functional-z-j-230425.webp)

B1. the Generating Functional Z[J]

B1. The generating functional Z[J] The generating functional Z[J] is a key object in quantum field theory - as we shall see it reduces in ordinary quantum mechanics to a limiting form of the 1-particle propagator G(x; x0jJ) when the particle is under thje influence of an external field J(t). However, before beginning, it is useful to look at another closely related object, viz., the generating functional Z¯(J) in ordinary probability theory. Recall that for a simple random variable φ, we can assign a probability distribution P (φ), so that the expectation value of any variable A(φ) that depends on φ is given by Z hAi = dφP (φ)A(φ); (1) where we have assumed the normalization condition Z dφP (φ) = 1: (2) Now let us consider the generating functional Z¯(J) defined by Z Z¯(J) = dφP (φ)eφ: (3) From this definition, it immediately follows that the "n-th moment" of the probability dis- tribution P (φ) is Z @nZ¯(J) g = hφni = dφP (φ)φn = j ; (4) n @J n J=0 and that we can expand Z¯(J) as 1 X J n Z Z¯(J) = dφP (φ)φn n! n=0 1 = g J n; (5) n! n ¯ so that Z(J) acts as a "generator" for the infinite sequence of moments gn of the probability distribution P (φ). For future reference it is also useful to recall how one may also expand the logarithm of Z¯(J); we write, Z¯(J) = exp[W¯ (J)] Z W¯ (J) = ln Z¯(J) = ln dφP (φ)eφ: (6) 1 Now suppose we make a power series expansion of W¯ (J), i.e., 1 X 1 W¯ (J) = C J n; (7) n! n n=0 where the Cn, known as "cumulants", are just @nW¯ (J) C = j : (8) n @J n J=0 The relationship between the cumulants Cn and moments gn is easily found. -

Complex Sinusoids Copyright C Barry Van Veen 2014

Complex Sinusoids Copyright c Barry Van Veen 2014 Feel free to pass this ebook around the web... but please do not modify any of its contents. Thanks! AllSignalProcessing.com Key Concepts 1) The real part of a complex sinusoid is a cosine wave and the imag- inary part is a sine wave. 2) A complex sinusoid x(t) = AejΩt+φ can be visualized in the complex plane as a vector of length A that is rotating at a rate of Ω radians per second and has angle φ relative to the real axis at time t = 0. a) The projection of the complex sinusoid onto the real axis is the cosine A cos(Ωt + φ). b) The projection of the complex sinusoid onto the imaginary axis is the cosine A sin(Ωt + φ). AllSignalProcessing.com 3) The output of a linear time invariant system in response to a com- plex sinusoid input is a complex sinusoid of the of the same fre- quency. The system only changes the amplitude and phase of the input complex sinusoid. a) Arbitrary input signals are represented as weighted sums of complex sinusoids of different frequencies. b) Then, the output is a weighted sum of complex sinusoids where the weights have been multiplied by the complex gain of the system. 4) Complex sinusoids also simplify algebraic manipulations. AllSignalProcessing.com 5) Real sinusoids can be expressed as a sum of a positive and negative frequency complex sinusoid. 6) The concept of negative frequency is not physically meaningful for real data and is an artifact of using complex sinusoids. -

Percent R, X and Z Based on Transformer KVA

SHORT CIRCUIT FAULT CALCULATIONS Short circuit fault calculations as required to be performed on all electrical service entrances by National Electrical Code 110-9, 110-10. These calculations are made to assure that the service equipment will clear a fault in case of short circuit. To perform the fault calculations the following information must be obtained: 1. Available Power Company Short circuit KVA at transformer primary : Contact Power Company, may also be given in terms of R + jX. 2. Length of service drop from transformer to building, Type and size of conductor, ie., 250 MCM, aluminum. 3. Impedance of transformer, KVA size. A. %R = Percent Resistance B. %X = Percent Reactance C. %Z = Percent Impedance D. KVA = Kilovoltamp size of transformer. ( Obtain for each transformer if in Bank of 2 or 3) 4. If service entrance consists of several different sizes of conductors, each must be adjusted by (Ohms for 1 conductor) (Number of conductors) This must be done for R and X Three Phase Systems Wye Systems: 120/208V 3∅, 4 wire 277/480V 3∅ 4 wire Delta Systems: 120/240V 3∅, 4 wire 240V 3∅, 3 wire 480 V 3∅, 3 wire Single Phase Systems: Voltage 120/240V 1∅, 3 wire. Separate line to line and line to neutral calculations must be done for single phase systems. Voltage in equations (KV) is the secondary transformer voltage, line to line. Base KVA is 10,000 in all examples. Only those components actually in the system have to be included, each component must have an X and an R value. Neutral size is assumed to be the same size as the phase conductors. -

The Constraint on Public Debt When R<G but G<M

The constraint on public debt when r < g but g < m Ricardo Reis LSE March 2021 Abstract With real interest rates below the growth rate of the economy, but the marginal prod- uct of capital above it, the public debt can be lower than the present value of primary surpluses because of a bubble premia on the debt. The government can run a deficit forever. In a model that endogenizes the bubble premium as arising from the safety and liquidity of public debt, more government spending requires a larger bubble pre- mium, but because people want to hold less debt, there is an upper limit on spending. Inflation reduces the fiscal space, financial repression increases it, and redistribution of wealth or income taxation have an unconventional effect on fiscal capacity through the bubble premium. JEL codes: D52, E62, G10, H63. Keywords: Debt limits, debt sustainability, incomplete markets, misallocation. * Contact: [email protected]. I am grateful to Adrien Couturier and Rui Sousa for research assistance, to John Cochrane, Daniel Cohen, Fiorella de Fiore, Xavier Gabaix, N. Gregory Mankiw, Jean-Charles Rochet, John Taylor, Andres Velasco, Ivan Werning, and seminar participants at the ASSA, Banque de France - PSE, BIS, NBER Economic Fluctuations group meetings, Princeton University, RIDGE, and University of Zurich for comments. This paper was written during a Lamfalussy fellowship at the BIS, whom I thank for its hospitality. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, INFL, under grant number No. GA: 682288. First draft: November 2020. 1 Introduction Almost every year in the past century (and maybe longer), the long-term interest rate on US government debt (r) was below the growth rate of output (g). -

Reading Source Data in R

Reading Source Data in R R is useful for analyzing data, once there is data to be analyzed. Real datasets come from numerous places in various formats, many of which actually can be leveraged by the savvy R programmer with the right set of packages and practices. *** Note: It is possible to stream data in R, but it’s probably outside of the scope of most educational uses. We will only be worried about static data. *** Understanding the flow of data How many times have you accessed some information in a browser or software package and wished you had that data as a spreadsheet or csv instead? R, like most programming languages, can serve as the bridge between the information you have and the information you want. A significant amount of programming is an exercise in changing file formats. Source Result Data R Data To use R for data manipulation and analysis, source data must be read in, analyzed or manipulated as necessary, and the results are output in some meaningful format. This document focuses on the red arrow: How is source data read into R? The ability to access data is fundamental to building useful, productive systems, and is sometimes the biggest challenge Immediately preceding the scope of this document is the source data itself. It is left to the reader to understand the source data: How and where it is stored, in what file formats, file ownership and permissions, etc. Immediately beyond the scope of this document is actual programming. It is left to the reader to determine which tools and methods are best applied to the source data to yield the desired results.