A Game Plan to Conserve the Interscholastic Athletic Environment After Lebron James Kevin P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Tribute to Champions

HLETIC C AT OM M A IS M S O I C O A N T Tribute to Champions May 30th, 2019 McGavick Conference Center, Lakewood, WA FEATURING CONNELLY LAW OFFICES EXCELLENCE IN OFFICIATING AWARD • Boys Basketball–Mike Stephenson • Girls Basketball–Hiram “BJ” Aea • Football–Joe Horn • Soccer–Larry Baughman • Softball–Scott Buser • Volleyball–Peter Thomas • Wrestling–Chris Brayton FROSTY WESTERING EXCELLENCE IN COACHING AWARD Patty Ley, Cross Country Coach, Gig Harbor HS Paul Souza, Softball & Volleyball Coach, Washington HS FIRST FAMILY OF SPORTS AWARD The McPhee Family—Bill and Georgia (parents) and children Kathy, Diane, Scott, Colleen, Brad, Mark, Maureen, Bryce and Jim DOUG MCARTHUR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Willie Stewart, Retired Lincoln HS Principal Dan Watson, Retired Lincoln HS Track Coach DICK HANNULA MALE & FEMALE AMATEUR ATHLETE OF THE YEAR AWARD Jamie Lange, Basketball and Soccer, Sumner/Univ. of Puget Sound Kaleb McGary, Football, Fife/Univ. of Washington TACOMA-PIERCE COUNTY SPORTS HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES • Baseball–Tony Barron • Basketball–Jim Black, Jennifer Gray Reiter, Tim Kelly and Bob Niehl • Bowling–Mike Karch • Boxing–Emmett Linton, Jr. and Bobby Pasquale • Football–Singor Mobley • Karate–Steve Curran p • Media–Bruce Larson (photographer) • Snowboarding–Liz Daley • Swimming–Dennis Larsen • Track and Field–Pat Tyson and Joel Wingard • Wrestling–Kylee Bishop 1 2 The Tacoma Athletic Commission—Celebrating COMMITTEE and Supporting Students and Amateur Athletics Chairman ������������������������������Marc Blau for 76 years in Pierce -

University of Maryland Men's Basketball Media Guides

>•>--«- H JMl* . T » - •%Jfc» rf*-"'*"' - T r . /% /• #* MARYLAND BASKETBALL 1986-87 1986-87 Schedule . Date Opponent Site Time Dec. 27 Winthrop Home 8 PM 29 Fairleigh Dickinson Home 8 PM 31 Notre Dame Home 7 PM Jan. 3 N.C. State Away 7 PM 5 Towson Home 8 PM 8 North Carolina Away 9 PM 10 Virginia Home 4 PM 14 Duke Home 8 PM 17 Clemson Away 4 PM 19 Buc knell Home 8 PM 21 West Virginia Home 8 PM 24 Old Dominion Away 7:30 PM 28 James Madison Away 7:30 PM Feb. 1 Georgia Tech Away 3 PM 2 Wake Forest Away 8 PM 4 Clemson Home 8 PM 7 Duke Away 4 PM 10 Georgia Tech Home 9 PM 14 North Carolina Home 4 PM 16 Central Florida Home 8 PM 18 Maryland-Baltimore County Home 8 PM 22 Wake Forest Home 4 PM 25 N.C. State Home 8 PM 27 Maryland-Eastern Shore Home 8 PM Mar. 1 Virginia Away 3 PM 6-7-8 ACC Tournament Landover, Maryland 1986-87 BASKETBALL GUIDE Table of Contents Section I: Administration and Coaching Staff 5 Section III: The 1985-86 Season 51 Assistant Coaches 10 ACC Standings and Statistics 58 Athletic Department Biographies 11 Final Statistics, 1985-86 54 Athletic Director — Charles F. Sturtz 7 Game-by-Game Scoring 56 Chancellor — John B. Slaughter 6 Game Highs — Individual and Team 57 Cole Field House 15 Game Leaders and Results 54 Conference Directory 16 Maryland Hoopourri: Past and Present 60 Head Coach — Bob Wade 8 Points Per Possession 58 President — John S. -

Brett Reed St

SCHEDULE/RESULTS (0-0, 0-0 PATRIOT LEAGUE) LEHIGH Nov. 9 at St. John’s (1) 7:00 (ESPN2/ESPN3.com) 12 at Iowa State 2:00 PM (ET) MEN’S BASKETBALL 15 at Fairleigh Dickinson 7:00 PM 18 vs. William & Mary (2) 4:30 PM 19 at Liberty (2) 7:00 PM Junior C.J. McCollum 20 vs. Eastern Kentucky (2) 2:30 PM Nation’s Leading Returning Scorer (21.8 PPG) 28 QUINNIPIAC 7:00 PM Dec. GAME 1: LEHIGH AT ST. JOHN’S 1 at Fordham 7:00 PM 3 at Cornell 7:00 PM LEHIGH MOUNTAIN HAWKS (0-0, 0-0 PL) at 7 SAINT FRANCIS (Pa.) 7:30 PM 10 at Wagner 4:00 PM ST. JOHN’S RED STORM (0-0, 0-0 BIG EAST) 12 ARCADIA 7:00 PM Record prior to St. John’s game vs. William & Mary Monday 22 at Michigan State 9:00 PM (ESPNU) 28 at Saint Peter’s 7:00 PM 2K SPORTS CLASSIC BENEFITING COACHES VS. CANCER 31 at Bryant 1:00 PM CARNESECCA ARENA (6,080) • QUEENS, N.Y. Jan. WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2011 • 7:00 PM 3 MARYLAND EASTERN SHORE 7:00 PM 7 at Holy Cross* 3:30 PM ESPN2/ESPN3.com (BOB WISCHUSEN & LEN ELMORE) 11 AMERICAN* 7:00 PM 14 at Colgate* 2:00 PM SETTING THE SCENE 18 BUCKNELL* 7:00 PM The Lehigh men’s basketball team kicks off its much-anticipated 2011-12 season on Wednes- 22 at Lafayette* 2:00 PM (CBS SN) day when it travels to St. -

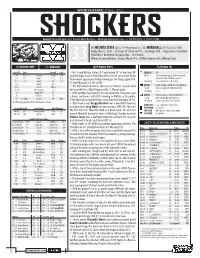

WICHITA STATE BASKETBALL TUNING in OPENING TIPS No. 4

WICHITA STATE BASKETBALL Contact: Bryan Holmgren, Asst. Director/Media Relations • [email protected] • o: 316-978-5535 • c: 316-841-6206 [4] WICHITA STATE (25-7, 14-4 American) vs. [13] MARSHALL (24-10, 12-6 C-USA) Friday, Mar. 16, 2018 • 12:30 pm CT (10:30 am PT) • San Diego, Calif. • Viejas Arena at Aztec Bowl NCAA Men's Basketball Championship • First Round 33 Winner to Second Round: Sunday, March 18 vs. [5] West Virginia or [12] Murray State [4] WICHITA STATE [13] MARSHALL OPENING TIPS TUNING IN Overall Conf Overall Conf No. 4 seed Wichita State (25-7 and ranked 16th in the latest AP TELECAST TNT 25-7 14-4 Record 24-10 12-6 and USA Today Coaches Polls) tips off its seventh-consecutive NCAA Talent: Carter Blackburn (pbp), Debbie Antonelli 13-3 7-2 Home 15-2 7-2 Tournament appearance Friday morning in San Diego against No. (analyst) & John Schriffen (reporter) 9-2 7-2 Away 6-8 5-4 Streaming ncaa.com/march-madness-live 3-2 Neutral 3-0 13 seed Marshall (24-10) on TNT. The WSU-Marshall winner advances to Sunday's second round RADIO Shocker Radio // KEYN 103.7 FM (Wichita) Lost 1 Streak Won 4 Talent: Mike Kennedy, Bob Hull & Dave Dahl 16 / 16 AP / Coaches -/- to face either No. 5 West Virginia or No. 12 Murray State. Streaming: none 16 NCAA RPI* 87 WSU and Marshall meet for just the third time. The teams split 20 KenPom* 114 a home-and-home, with WSU winning in Wichita in December, RADIO Westwood One // Sirius 145 & XM 203 14 At-Large S-Curve 54 Auto Talent: John Sadak & Mike Montgomery 1940. -

Head Coach Jamie Dixon

DATE OPPONENT (TV) TIME Nov. 6 CARNEGIE-MELLON (Exh.) 7:00 pm Nov. 14 GANNON UNIVERSITY (Exh.) 7:00 pm Nov. 20 HOWARD 7:00 pm Nov. 24 ROBERT MORRIS 7:00 pm Nov. 27 LOYOLA (Md.) 7:00 pm Dec. 1 ST. FRANCIS (Pa.) 7:00 pm Dec. 4 DUQUESNE (FSN) 4:00 pm Dec. 7 Jimmy V. Classic vs. Memphis (ESPN) 7:00 pm Dec. 11 at Penn State (FSN) 2:00 pm Dec. 18 COPPIN STATE 7:00 pm Dec. 23 RICHMOND (ESPN2) 7:00 pm 2004-2005 PITTSBURGH PANTHERS BASKETBALL Dec. 29 SOUTH CAROLINA (FSN) 7:00 pm Jan. 2 BUCKNELL 7:00 pm Jan. 5 *GEORGETOWN (FSN) 7:00 pm Jan. 8 at *Rutgers (FSN) 2:00 pm Jan. 15 *SETON HALL (WTAE) Noon Jan. 18 at *St. John’s (FSN) 7:30 pm Jan. 22 at *Connecticut (ESPN) 9:00 pm Jan. 29 *SYRACUSE (ESPN) 7:00 pm Jan. 31 *PROVIDENCE (ESPN2) 9:00 pm Feb. 5 at *West Virginia (ESPN2) 6:00 pm Feb. 8 *ST. JOHN’S (FSN) 7:00 pm Feb. 12 *NOTRE DAME (ESPN) Noon Feb. 14 at *Syracuse (ESPN) 7:00 pm Feb. 20 at *Villanova (ABC) 1:30 pm Feb. 23 *WEST VIRGINIA (FSN) 7:00 pm Feb. 26 *CONNECTICUT (CBS) 3:45 pm Feb. 28 *at Boston College (ESPN) 7:00 pm March 5 at *Notre Dame (CBS) 2:00 pm March 9-12 Big East Championship TBA March 17-20 NCAA First & Second Rounds TBA March 24-27 NCAA Regionals TBA April 2-4 NCAA Final Four TBA All home games played in the Petersen Events Center on the University of Pittsburgh campus. -

NCAA Division I Football Records (Coaching Records)

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............. 2 Football Bowl Subdivision Coaching Records .................................... 5 Football Championship Subdivision Coaching Records .......... 15 Coaching Honors ......................................... 21 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COachING RECOrds All-Divisions Coaching Records Coach (Alma Mater) Winningest Coaches All-Time (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 35. Pete Schmidt (Alma 1970) ......................................... 14 104 27 4 .785 (Albion 1983-96) BY PERCENTAGE 36. Jim Sochor (San Fran. St. 1960)................................ 19 156 41 5 .785 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four-year colleges (regardless (UC Davis 1970-88) of division or association). Bowl and playoff games included. 37. *Chris Creighton (Kenyon 1991) ............................. 13 109 30 0 .784 Coach (Alma Mater) (Ottawa 1997-00, Wabash 2001-07, Drake 08-09) (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 38. *John Gagliardi (Colorado Col. 1949).................... 61 471 126 11 .784 1. *Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) ........................ 24 289 22 3 .925 (Carroll [MT] 1949-52, (Mount Union 1986-09) St. John’s [MN] 1953-09) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) ......................... 13 105 12 5 .881 39. Bill Edwards (Wittenberg 1931) ............................... 25 176 46 8 .783 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Case Tech 1934-40, Vanderbilt 1949-52, 3. Frank Leahy (Notre Dame 1931) ............................. 13 107 13 9 .864 Wittenberg 1955-68) (Boston College 1939-40, 40. Gil Dobie (Minnesota 1902) ...................................... 33 180 45 15 .781 Notre Dame 41-43, 46-53) (North Dakota St. 1906-07, Washington 4. Bob Reade (Cornell College 1954) ......................... 16 146 23 1 .862 1908-16, Navy 1917-19, Cornell 1920-35, (Augustana [IL] 1979-94) Boston College 1936-38) 5. -

Coach JT Curtis Headed for 500 Career Victory

Profile: Coach J. T. Curtis Headed for 500 th Career Victory Updated 10-9-11 J. T. Curtis, head football coach at John Curtis Christian School in River Ridge, LA, is closing in on the 500-win mark which would make him only the second coach in history—high school, college or professional--to reach that remarkable milestone . His record to date is 499-54-6, a winning percentage of .898. After going 0-10 his first year of coaching in 1969¸ Curtis has never had a losing record since. Spanning a total of 42 seasons, Curtis’ teams have: • Won 23 state championships in 30 trips to the title game (both state records). • Reached the state championship game the past 16 consecutive years, winning 11 (1996-present). • Won 5 straight championships (2004-08), also a state record. • Recorded double-digit victories (10 or more wins) for the past 35 consecutive seasons—since 1 st year of coaching—(1976-2010); record 499-44-6 through that stretch is winning percentage of 91.7%. • Won the district championship 34 of the last 35 seasons. • Reached the state playoffs the past 36 consecutive seasons. • Reached the state playoffs a total of 38 times. • Posted 11 perfect seasons. • Been undefeated in the regular season 16 times. Curtis, who will be 65 years old on Dec. 6, 2011, has also coached the Patriots to six state baseball championships. In addition to his coaching responsibilities, Curtis is the school’s headmaster, is an ordained minister and is a devoted family man with nine grandchildren and numerous family ties to the school’s administration and coaching staff. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 4/4/2020 Anaheim Ducks Nashville Predators 1182159 When Teemu Selanne became a Stanley Cup champion 1182183 Predators fan survey: How do readers feel about the direction of the team? Arizona Coyotes 1182160 Arizona Coyotes get time for hobbies, family with season New Jersey Devils on hold 1182184 Scouting Devils’ 2019 draft class: Patrick Moynihan ‘really 1182161 Coyotes in the playoffs! 10 thoughts on the (original) end valuable’ because he has ‘versatility and adaptabi of the regular season New York Islanders Boston Bruins 1182185 Islanders’ Johnny Boychuk left unrecognizable by scary 1182162 Talk about a fantasy draft: Here are the ultimate cap-era skate gash Bruins teams 1182186 Barry Trotz, Lou Lamoriello praise Gov. Cuomo's 1182163 Bruins' Brad Marchand voted best AND worst trash-talker leadership amid coronavirus situation in NHL players' poll 1182164 Bruins legend Bobby Orr's great feat from April 3, 1971 New York Rangers still hasn't been matched 1182187 Rangers Prospect K’Andre Miller Faces Racial Abuse in a Team Video Chat Buffalo Sabres 1182188 Rangers fan video chat with prospect K’Andre Miller 1182165 Sabres' prospects preparing in case Amerks' season interrupted by racist hacker resumes 1182189 Rangers’ K’Andre Miller chat zoom-bombed by racist trolls 1182190 Henrik Lundqvist’s Rangers end is hard to digest Calgary Flames 1182191 NY Rangers assistant GM Chris Drury discusses K'Andre 1182166 Flames superstar Gaudreau piling firewood during NHL Miller, other college signings pause 1182192 Rangers, -

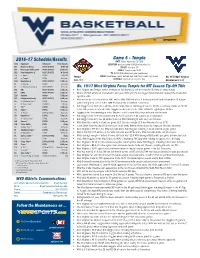

2016-17 Basketball Notes.Indd

Game 5 - Temple 2016-17 Schedule/Results DATE: Friday, November 25, 2016 Date Opponent Television Time/Results LOCATION: Barclays Center (18,103) in Brooklyn, N.Y. N11 Mount St. Mary’s ROOT SPORTS W/87-59 TIPOFF: 3:00 p.m. ET N14 Mississippi Valley State ROOT SPORTS W/107-66 SERIES: Temple leads 36-34 N20 New Hampshire & ROOT SPORTS W/100-41 TV: ESPN2 (Rich Hollenberg and Len Elmore) N24 vs. Illinois ^ ESPNU W/89-57 Temple RADIO: Mountaineer Sports Network from IMG (Tony Caridi & Jay Jacobs) No. 19/17 West Virginia N25 vs. Temple ^ ESPN2 3:00 p.m. OFFICIALS: Announced on game day N28 Manhattan & ROOT SPORTS 7:00 p.m. Owls (3-2) Mountaineers (4-0) D3 at Virginia ESPNU 2:00 p.m. D7 vs. Western Carolina # ROOT SPORTS 7:00 p.m. No. 19/17 West Virginia Faces Temple for NIT Season Tip-Off Title D10 VMI ROOT SPORTS 2:00 p.m. • West Virginia and Temple, former members of the Atlantic 10, will meet for the 71st time in school history. D17 UMKC ROOT SPORTS 2:00 p.m. • WVU is 247-164 all-time in tournaments. Last year, WVU won the Las Vegas Invitational and captured the Puerto Rico D20 Radford Nextar 7:00 p.m. Tip-Off in 2014. D23 Northern Kentucky ROOT SPORTS 4:00 p.m. • WVU was in the Preseason NIT in 1992 and in 1986. WVU lost at No. 4 Kentucky in 1992 and defeated No. 10 Auburn D30 at Oklahoma State * ESPN2 4:00 p.m. -

University of Maryland Men's Basketball Media Guides

1 ,™ maw > -J?. k uruo xavo^jj 1981-82 TERRAPIN BASKETBALL SCHEDULE Day Date Opponent Time Location NOVEMBER Wed. 18 Australian National Team 8:00 Cole Field House (Exhibition) Fri. 27 St. Peters 8:00 Cole Field House Sun. 29 Lafayette 8:00 Cole Field House DECEMBER Wed. 2 Long Island University 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 5 George Mason 8:00 Cole Field House TV Mon. 7 U.M. -Eastern Shore 8:00 Cole Field House Wed. 9 Towson State University 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 12 North Carolina State 1:00 Raleigh, N.C. TV Sat. 19 Ohio University 7:30 Cole Field House TV Wed. 23 Georgia Tech 8:00 Cole Field House Tues. 29 U.C.L.A. 8:30 PCT Los Angeles, CA TV JANUARY Wed. 6 North Carolina 7:00 Cole Field House TV Sat. 9 Duke 8:00 Durham, N.C. TV Tues. 12 Virginia 8:00 Charlottesville, VA TV Sat. 16 Clemson 3:30 Cole Field House TV Wed. 20 Canisius 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 23 Notre Dame 1:30 South Bend, IN TV Wed. 27 William & Mary 7:30 Williamsbui'g, VA Sat. 30 Georgia Tech 1:00 Atlanta, GA TV FEBRUARY Wed. 3 Wake Forest 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 6 Duke 3:00 Cole Field House TV Sun. 7 Hofstra 8:00 Cole Field House Thurs. 11 North Carolina 8:00 Chapel Hill , NC TV Wed. 17 Clemson 8:00 Clemson, SC Sat. 20 Wake Forest 8:00 Greensboro i NC f Wed. 24 North Carolina State 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. -

The Football Coaching Bible (The Coaching Bible) by American Football Coaches Association

The Football Coaching Bible (The Coaching Bible) by American Football Coaches Association Ebook The Football Coaching Bible (The Coaching Bible) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Football Coaching Bible (The Coaching Bible) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: The Coaching Bible+++Paperback:::: 376 pages+++Publisher:::: Human Kinetics, Inc.; First edition (August 15, 2002)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0736044116+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0736044110+++Product Dimensions::::7 x 0.9 x 10 inches++++++ ISBN10 0736044116 ISBN13 978-0736044 Download here >> Description: The Football Coaching Bible features many of the games most successful coaches. Each shares the special insight, advice, and strategies theyve used to field championship-winning teams season after season.The 27 chapter contributing coaches span six decades of the sport and reach into every corner of the United States. The impressive list of contributors:-Joe Paterno-Hayden Fry-Phil Fulmer-Dick Foster-Grant Teaff-Gene Stallings-Jim Tressel-R.C. Slocum-LaVell Edwards-Bobby Bowden-Jim Young-Frosty Westering-Mack Brown-Larry Kehres-Bill Snyder-Lou Holtz-Ken Sparks-Tom Osborne-Sonny Lubick-Mike Bellotti-Barry Alvarez-Fisher DeBerry-George Curry-Bo Schembechler-Joe Tiller-Frank BeamerThey cover every aspect of the game: coaching principles, program building, player motivation, practice sessions, individual skills, team tactics, offensive and defensive play-calling, and performance evaluation.Developed by the American Football Coaches Association, this coaching guide establishes a new standard of excellence in the sport. This book doesnt have the greatest Xs and Os. It doesnt plan workouts or practice schedules.