NCAA Student-Athlete Name & Likeness Licensing Litigation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Maryland Men's Basketball Media Guides

>•>--«- H JMl* . T » - •%Jfc» rf*-"'*"' - T r . /% /• #* MARYLAND BASKETBALL 1986-87 1986-87 Schedule . Date Opponent Site Time Dec. 27 Winthrop Home 8 PM 29 Fairleigh Dickinson Home 8 PM 31 Notre Dame Home 7 PM Jan. 3 N.C. State Away 7 PM 5 Towson Home 8 PM 8 North Carolina Away 9 PM 10 Virginia Home 4 PM 14 Duke Home 8 PM 17 Clemson Away 4 PM 19 Buc knell Home 8 PM 21 West Virginia Home 8 PM 24 Old Dominion Away 7:30 PM 28 James Madison Away 7:30 PM Feb. 1 Georgia Tech Away 3 PM 2 Wake Forest Away 8 PM 4 Clemson Home 8 PM 7 Duke Away 4 PM 10 Georgia Tech Home 9 PM 14 North Carolina Home 4 PM 16 Central Florida Home 8 PM 18 Maryland-Baltimore County Home 8 PM 22 Wake Forest Home 4 PM 25 N.C. State Home 8 PM 27 Maryland-Eastern Shore Home 8 PM Mar. 1 Virginia Away 3 PM 6-7-8 ACC Tournament Landover, Maryland 1986-87 BASKETBALL GUIDE Table of Contents Section I: Administration and Coaching Staff 5 Section III: The 1985-86 Season 51 Assistant Coaches 10 ACC Standings and Statistics 58 Athletic Department Biographies 11 Final Statistics, 1985-86 54 Athletic Director — Charles F. Sturtz 7 Game-by-Game Scoring 56 Chancellor — John B. Slaughter 6 Game Highs — Individual and Team 57 Cole Field House 15 Game Leaders and Results 54 Conference Directory 16 Maryland Hoopourri: Past and Present 60 Head Coach — Bob Wade 8 Points Per Possession 58 President — John S. -

Brett Reed St

SCHEDULE/RESULTS (0-0, 0-0 PATRIOT LEAGUE) LEHIGH Nov. 9 at St. John’s (1) 7:00 (ESPN2/ESPN3.com) 12 at Iowa State 2:00 PM (ET) MEN’S BASKETBALL 15 at Fairleigh Dickinson 7:00 PM 18 vs. William & Mary (2) 4:30 PM 19 at Liberty (2) 7:00 PM Junior C.J. McCollum 20 vs. Eastern Kentucky (2) 2:30 PM Nation’s Leading Returning Scorer (21.8 PPG) 28 QUINNIPIAC 7:00 PM Dec. GAME 1: LEHIGH AT ST. JOHN’S 1 at Fordham 7:00 PM 3 at Cornell 7:00 PM LEHIGH MOUNTAIN HAWKS (0-0, 0-0 PL) at 7 SAINT FRANCIS (Pa.) 7:30 PM 10 at Wagner 4:00 PM ST. JOHN’S RED STORM (0-0, 0-0 BIG EAST) 12 ARCADIA 7:00 PM Record prior to St. John’s game vs. William & Mary Monday 22 at Michigan State 9:00 PM (ESPNU) 28 at Saint Peter’s 7:00 PM 2K SPORTS CLASSIC BENEFITING COACHES VS. CANCER 31 at Bryant 1:00 PM CARNESECCA ARENA (6,080) • QUEENS, N.Y. Jan. WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2011 • 7:00 PM 3 MARYLAND EASTERN SHORE 7:00 PM 7 at Holy Cross* 3:30 PM ESPN2/ESPN3.com (BOB WISCHUSEN & LEN ELMORE) 11 AMERICAN* 7:00 PM 14 at Colgate* 2:00 PM SETTING THE SCENE 18 BUCKNELL* 7:00 PM The Lehigh men’s basketball team kicks off its much-anticipated 2011-12 season on Wednes- 22 at Lafayette* 2:00 PM (CBS SN) day when it travels to St. -

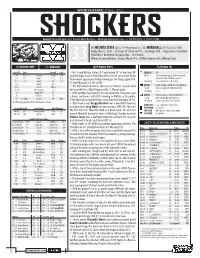

WICHITA STATE BASKETBALL TUNING in OPENING TIPS No. 4

WICHITA STATE BASKETBALL Contact: Bryan Holmgren, Asst. Director/Media Relations • [email protected] • o: 316-978-5535 • c: 316-841-6206 [4] WICHITA STATE (25-7, 14-4 American) vs. [13] MARSHALL (24-10, 12-6 C-USA) Friday, Mar. 16, 2018 • 12:30 pm CT (10:30 am PT) • San Diego, Calif. • Viejas Arena at Aztec Bowl NCAA Men's Basketball Championship • First Round 33 Winner to Second Round: Sunday, March 18 vs. [5] West Virginia or [12] Murray State [4] WICHITA STATE [13] MARSHALL OPENING TIPS TUNING IN Overall Conf Overall Conf No. 4 seed Wichita State (25-7 and ranked 16th in the latest AP TELECAST TNT 25-7 14-4 Record 24-10 12-6 and USA Today Coaches Polls) tips off its seventh-consecutive NCAA Talent: Carter Blackburn (pbp), Debbie Antonelli 13-3 7-2 Home 15-2 7-2 Tournament appearance Friday morning in San Diego against No. (analyst) & John Schriffen (reporter) 9-2 7-2 Away 6-8 5-4 Streaming ncaa.com/march-madness-live 3-2 Neutral 3-0 13 seed Marshall (24-10) on TNT. The WSU-Marshall winner advances to Sunday's second round RADIO Shocker Radio // KEYN 103.7 FM (Wichita) Lost 1 Streak Won 4 Talent: Mike Kennedy, Bob Hull & Dave Dahl 16 / 16 AP / Coaches -/- to face either No. 5 West Virginia or No. 12 Murray State. Streaming: none 16 NCAA RPI* 87 WSU and Marshall meet for just the third time. The teams split 20 KenPom* 114 a home-and-home, with WSU winning in Wichita in December, RADIO Westwood One // Sirius 145 & XM 203 14 At-Large S-Curve 54 Auto Talent: John Sadak & Mike Montgomery 1940. -

Head Coach Jamie Dixon

DATE OPPONENT (TV) TIME Nov. 6 CARNEGIE-MELLON (Exh.) 7:00 pm Nov. 14 GANNON UNIVERSITY (Exh.) 7:00 pm Nov. 20 HOWARD 7:00 pm Nov. 24 ROBERT MORRIS 7:00 pm Nov. 27 LOYOLA (Md.) 7:00 pm Dec. 1 ST. FRANCIS (Pa.) 7:00 pm Dec. 4 DUQUESNE (FSN) 4:00 pm Dec. 7 Jimmy V. Classic vs. Memphis (ESPN) 7:00 pm Dec. 11 at Penn State (FSN) 2:00 pm Dec. 18 COPPIN STATE 7:00 pm Dec. 23 RICHMOND (ESPN2) 7:00 pm 2004-2005 PITTSBURGH PANTHERS BASKETBALL Dec. 29 SOUTH CAROLINA (FSN) 7:00 pm Jan. 2 BUCKNELL 7:00 pm Jan. 5 *GEORGETOWN (FSN) 7:00 pm Jan. 8 at *Rutgers (FSN) 2:00 pm Jan. 15 *SETON HALL (WTAE) Noon Jan. 18 at *St. John’s (FSN) 7:30 pm Jan. 22 at *Connecticut (ESPN) 9:00 pm Jan. 29 *SYRACUSE (ESPN) 7:00 pm Jan. 31 *PROVIDENCE (ESPN2) 9:00 pm Feb. 5 at *West Virginia (ESPN2) 6:00 pm Feb. 8 *ST. JOHN’S (FSN) 7:00 pm Feb. 12 *NOTRE DAME (ESPN) Noon Feb. 14 at *Syracuse (ESPN) 7:00 pm Feb. 20 at *Villanova (ABC) 1:30 pm Feb. 23 *WEST VIRGINIA (FSN) 7:00 pm Feb. 26 *CONNECTICUT (CBS) 3:45 pm Feb. 28 *at Boston College (ESPN) 7:00 pm March 5 at *Notre Dame (CBS) 2:00 pm March 9-12 Big East Championship TBA March 17-20 NCAA First & Second Rounds TBA March 24-27 NCAA Regionals TBA April 2-4 NCAA Final Four TBA All home games played in the Petersen Events Center on the University of Pittsburgh campus. -

A Game Plan to Conserve the Interscholastic Athletic Environment After Lebron James Kevin P

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 14 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring A Game Plan to Conserve the Interscholastic Athletic Environment after LeBron James Kevin P. Braig Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Kevin P. Braig, A Game Plan to Conserve the Interscholastic Athletic Environment after LeBron James, 14 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 343 (2004) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol14/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GAME PLAN TO CONSERVE THE INTERSCHOLASTIC ATHLETIC ENVIRONMENT AFTER LEBRON JAMES KEVIN P. BRAIG Our sports are liturgies-but do not have dogmatic creeds. There is no long bill of doctrines all of us recite. We bring the hungers of our spirits, and many of them, not all, are filled-filled with a beauty, ex- cellence, and grace few other institutions now afford. Our sports need to be reformed-Ecclesia semper reformanda. Let not too much be claimed for them. But what they do superbly needs our thanks, our watchfulness, our intellect, and our acerbic love.' I. INTRODUCTION For decades, the community of high schools in the Ohio High School Ath- letic Association (OHSAA) has sought to regulate interscholastic athletics by prohibiting external influences upon students that are potentially inconsistent with the educational and community values of athletic participation. Tradi- tionally, the recruiting of a student for athletic purposes has been the primary influence that the OHSAA membership has sought to combat. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 4/4/2020 Anaheim Ducks Nashville Predators 1182159 When Teemu Selanne became a Stanley Cup champion 1182183 Predators fan survey: How do readers feel about the direction of the team? Arizona Coyotes 1182160 Arizona Coyotes get time for hobbies, family with season New Jersey Devils on hold 1182184 Scouting Devils’ 2019 draft class: Patrick Moynihan ‘really 1182161 Coyotes in the playoffs! 10 thoughts on the (original) end valuable’ because he has ‘versatility and adaptabi of the regular season New York Islanders Boston Bruins 1182185 Islanders’ Johnny Boychuk left unrecognizable by scary 1182162 Talk about a fantasy draft: Here are the ultimate cap-era skate gash Bruins teams 1182186 Barry Trotz, Lou Lamoriello praise Gov. Cuomo's 1182163 Bruins' Brad Marchand voted best AND worst trash-talker leadership amid coronavirus situation in NHL players' poll 1182164 Bruins legend Bobby Orr's great feat from April 3, 1971 New York Rangers still hasn't been matched 1182187 Rangers Prospect K’Andre Miller Faces Racial Abuse in a Team Video Chat Buffalo Sabres 1182188 Rangers fan video chat with prospect K’Andre Miller 1182165 Sabres' prospects preparing in case Amerks' season interrupted by racist hacker resumes 1182189 Rangers’ K’Andre Miller chat zoom-bombed by racist trolls 1182190 Henrik Lundqvist’s Rangers end is hard to digest Calgary Flames 1182191 NY Rangers assistant GM Chris Drury discusses K'Andre 1182166 Flames superstar Gaudreau piling firewood during NHL Miller, other college signings pause 1182192 Rangers, -

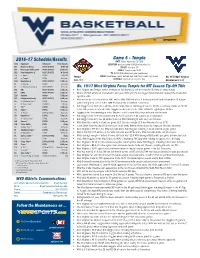

2016-17 Basketball Notes.Indd

Game 5 - Temple 2016-17 Schedule/Results DATE: Friday, November 25, 2016 Date Opponent Television Time/Results LOCATION: Barclays Center (18,103) in Brooklyn, N.Y. N11 Mount St. Mary’s ROOT SPORTS W/87-59 TIPOFF: 3:00 p.m. ET N14 Mississippi Valley State ROOT SPORTS W/107-66 SERIES: Temple leads 36-34 N20 New Hampshire & ROOT SPORTS W/100-41 TV: ESPN2 (Rich Hollenberg and Len Elmore) N24 vs. Illinois ^ ESPNU W/89-57 Temple RADIO: Mountaineer Sports Network from IMG (Tony Caridi & Jay Jacobs) No. 19/17 West Virginia N25 vs. Temple ^ ESPN2 3:00 p.m. OFFICIALS: Announced on game day N28 Manhattan & ROOT SPORTS 7:00 p.m. Owls (3-2) Mountaineers (4-0) D3 at Virginia ESPNU 2:00 p.m. D7 vs. Western Carolina # ROOT SPORTS 7:00 p.m. No. 19/17 West Virginia Faces Temple for NIT Season Tip-Off Title D10 VMI ROOT SPORTS 2:00 p.m. • West Virginia and Temple, former members of the Atlantic 10, will meet for the 71st time in school history. D17 UMKC ROOT SPORTS 2:00 p.m. • WVU is 247-164 all-time in tournaments. Last year, WVU won the Las Vegas Invitational and captured the Puerto Rico D20 Radford Nextar 7:00 p.m. Tip-Off in 2014. D23 Northern Kentucky ROOT SPORTS 4:00 p.m. • WVU was in the Preseason NIT in 1992 and in 1986. WVU lost at No. 4 Kentucky in 1992 and defeated No. 10 Auburn D30 at Oklahoma State * ESPN2 4:00 p.m. -

University of Maryland Men's Basketball Media Guides

1 ,™ maw > -J?. k uruo xavo^jj 1981-82 TERRAPIN BASKETBALL SCHEDULE Day Date Opponent Time Location NOVEMBER Wed. 18 Australian National Team 8:00 Cole Field House (Exhibition) Fri. 27 St. Peters 8:00 Cole Field House Sun. 29 Lafayette 8:00 Cole Field House DECEMBER Wed. 2 Long Island University 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 5 George Mason 8:00 Cole Field House TV Mon. 7 U.M. -Eastern Shore 8:00 Cole Field House Wed. 9 Towson State University 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 12 North Carolina State 1:00 Raleigh, N.C. TV Sat. 19 Ohio University 7:30 Cole Field House TV Wed. 23 Georgia Tech 8:00 Cole Field House Tues. 29 U.C.L.A. 8:30 PCT Los Angeles, CA TV JANUARY Wed. 6 North Carolina 7:00 Cole Field House TV Sat. 9 Duke 8:00 Durham, N.C. TV Tues. 12 Virginia 8:00 Charlottesville, VA TV Sat. 16 Clemson 3:30 Cole Field House TV Wed. 20 Canisius 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 23 Notre Dame 1:30 South Bend, IN TV Wed. 27 William & Mary 7:30 Williamsbui'g, VA Sat. 30 Georgia Tech 1:00 Atlanta, GA TV FEBRUARY Wed. 3 Wake Forest 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. 6 Duke 3:00 Cole Field House TV Sun. 7 Hofstra 8:00 Cole Field House Thurs. 11 North Carolina 8:00 Chapel Hill , NC TV Wed. 17 Clemson 8:00 Clemson, SC Sat. 20 Wake Forest 8:00 Greensboro i NC f Wed. 24 North Carolina State 8:00 Cole Field House Sat. -

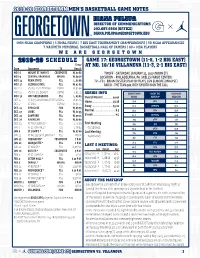

Omer Yurtseven Recorded His Eighth Double-Double with 10 Points and 11 Rebounds

2019-20 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 202.687.6564 (OFFICE) [email protected] 1984 NCAA CHAMPIONS | 5 FINAL FOURS | 7 BIG EAST TOURNAMENT CHAMPIONSHIPS | 30 NCAA APPEARANCES 7 NAISMITH MEMORIAL BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMERS | 60+ NBA PLAYERS WE ARE GEORGETOWN SCHEDULE GAME 17: GEORGETOWN (11-5, 1-2 BIG EAST) Time/ AT NO. 16/16 VILLANOVA (11-3, 2-1 BIG EAST) Date Opponent TV Result NOV. 6 MOUNT ST. MARY’S CBSSPORTS W, 81-68 TIPOFF – SATURDAY, JANUARY 11, 2020 (NOON ET) NOV. 9 CENTRAL ARKANSAS MASN2 W, 89-78 LOCATION – PHILADELPHIA, PA. (WELLS FARGO CENTER) NOV. 14 PENN STATE ! FS1 L, 81-66 TV – FS1 - BRIAN CUSTER (PLAY-BY-PLAY), LEN ELMORE (ANALYST) NOV. 17 GEORGIA STATE FS1 W, 91-83 RADIO – THE TEAM 980, RICH CHVOTKIN ON THE CALL NOV. 21 VS. NO. 22/22 TEXAS # ESPN2 W, 82-66 NOV. 22 VS. NO. 1/1 DUKE # ESPN2 L, 81-73 SERIES INFO GEORGETOWN ABOUT THE VILLANOVA NOV. 30 UNC GREENSBORO FS2 L, 65-61 Overall Record ............. 44-40 HOYAS MATCHUP WILDCATS DEC. 4 AT RV/25 OKLAHOMA STATE % ESPN+ W, 81-74 Home ............................ 23-16 79.6 PPG 75.1 DEC. 7 AT SMU ESPNU W, 91-74 Away ............................ 15-21 72.2 OPP PPG 67.1 DEC. 14 SYRACUSE FOX W, 89-79 DEC. 17 UMBC FS1 W, 81-55 Neutral ............................. 6-3 45.4 FG% 45.0 DEC. 21 SAMFORD FS1 W, 99-71 Streak ...............................w1 41.7 OPP FG% 43.9 DEC. 28 AMERICAN FS1 W, 80-60 103 3PM 128 DEC. -

Aw a Rd Wi N N E

Aw_MBB01_sp 11/21/00 8:50 AM Page 105 Awa r d Win n e r s Division I Consensus All-American Selections .. .1 0 6 Division I Academic All-Americans By Tea m .. .1 1 1 Division I Player of the Yea r. .1 1 2 Divisions II and III Fi r s t - Te a m All-Americans By Tea m. .1 1 4 Divisions II and III Ac a d e m i c All-Americans By Tea m. .1 1 6 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By Tea m. .1 1 7 Awar MBKB01 11/20/00 3:53 PM Page 106 10 6 DIVISION I CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICAN SELECTIONS Division I Consensus All-American Selections Second Tea m —R o b e r t Doll, Colorado; Wil f re d Un r uh, Bradley, 6-4, Toulon, Ill.; Bill Sharman, Southern By Season Do e rn e r , Evansville; Donald Burness, Stanford; George Ca l i f o r nia, 6-2, Porte r ville, Calif. Mu n r oe, Dartmouth; Stan Modzelewski, Rhode Island; Second Tea m —Charles Cooper, Duquesne; Don 192 9 John Mandic, Oregon St. Lofgran, San Francisco; Kevin O’Shea, Notre Dame; Don Charley Hyatt, Pittsburgh; Joe Schaaf, Pennsylvania; Rehfeldt, Wisconsin; Sherman White, Long Island. Charles Murphy, Purdue; Ver n Corbin, California; Thomas 1943 Ch u r chill, Oklahoma; John Thompson, Montana St. First Te a m— A n d rew Phillip, Illinois; Georg e 1951 193 0 Se n e s k y , St. Joseph’s; Ken Sailors, Wyoming; Harry Boy- First Tea m —Bill Mlkvy, Temple, 6-4, Palmerton, Pa.; ko f f, St. -

2011-12 USBWA Directory

U.S. BASKETBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION ALL-AMERICA TEAMS MEN’S ALL-AMERICA TEAMS MEN’S ALL-AMERICA TEAMS NATIONAL PLAYERS OF THE YEAR IN BOLDFACE 1964-65 1968-69 1956-57 1960-61 John Austin, Boston College Lew Alcindor, UCLA Elgin Baylor, Seattle Terry Dischinger, Purdue Rick Barry, Miami Spencer Haywood, Detroit Wilt Chamberlain, Kansas Roger Kaiser, Georgia Tech Bill Bradley, Princeton Dan Issel, Kentucky Chet Forte, Columbia Jerry Lucas, Ohio State A.W. Davis, Tennessee Mike Maloy, Davidson Frank Howard, Ohio State Bill McGill, Utah Wayne Estes, Utah State Pete Maravich, LSU Rod Hundley, West Virginia Tom Meschery, St. Mary’s Gail Goodrich, UCLA Jim McMillian, Columbia Jim Krebs, SMU Doug Moe, Notre Dame Fred Hetzel, Davidson Rick Mount, Purdue Guy Rodgers, Temple Gary Phillips, Houston Clyde Lee, Vanderbilt Calvin Murphy, Niagara Len Rosenbluth, North Carolina Larry Siegfried, Ohio State Cazzie Russell, Michigan Bud Ogden, Santa Clara Gary Thompson, Iowa State Tom Smith, St. Bonaventure Dave Stallworth, Wichita State Charlie Scott, North Carolina Charles Tyra, Louisville Chet Walker, Bradley Sidney Wicks, UCLA 1965-66 1957-58 1961-62 Dave Bing, Syracuse 1969-70 Elgin Baylor, Seattle Len Chappell, Wake Forest Clyde Lee, Vanderbilt Austin Carr, Notre Dame Bob Boozer, Kansas State Terry Dischinger, Purdue Jack Martin, Duke Jimmy Collins, New Mexico Pete Brennan, North Carolina Jack Foley, Holy Cross Dick Nemelka, BYU Dan Issel, Kentucky Wilt Chamberlain, Kansas John Havlicek, Ohio State Pat Riley, Kentucky Bob Lanier, St. Bonaventure Archie -

Loyola Ramblers @Ramblersmbb 2017-18 Game Notes

LOYOLA RAMBLERS @RAMBLERSMBB 2017-18 GAME NOTES GAME INFORMATION #11 LOYO( vs. #3 TENNESSEE DATE/TIME: Sat., March 17, 2018 / 5:10 p.m. CT SITE: American Airlines Center / Dallas, Texas RAMBLERS VOLUNTEERS TV/LIVE VIDEO: TNT 29-5 26-8 Spero Dedes (PBP), Steve Smith/Len Elmore (analysts) LIVE STATS: loyolaramblers.com TWITTER UPDATES: @RamblersMBB 35 - SERIES HISTORY: First Meeting GAME # AMERICAN AIRLINES CENTER - DAL(S, TEXAS OPENING TIP 2017-18 SCHEDULE 4 Loyola, which has won 11 straight games and 18 of its last 19 contests, posted its frst NOVEMBER NCAA Tournament win since March 16, 1985, when it stunned No. 22 Miami, 64-62 on 10 WRIGHT STATE (ESPN3) W, 84-80 Thursday. A win over Tennessee would give the Ramblers their frst-ever 30-win season 12 EUREKA (ESPN3) W, 96-69 in program history and their frst NCAA Sweet 16 appearance since 1984-85. 16 at UMKC (NBC Sports Chicago+) W, 66-56 4 Thursday’s win over Miami gave the Ramblers 29 wins on the season, matching the 19 SAMFORD # (ESPN3) W, 88-67 1962-63 NCAA championship team (29-2) for the most victories in school history. 21 MISSISSIPPI VALLEY STATE # (ESPN3) W, 63-50 4 At 29-5 overall, the Ramblers have recorded the 14th 20-win season in program his- 24 vs. UNC Wilmington # W, 102-78 tory and the second in the last four years under head coach Porter Moser. Prior to his 25 vs. Kent State # W, 75-60 arrival for the 2011-12 campaign, Loyola had one 20-win season in 26 years.